Indian microbrands are entering upscale circles, led by history-driven designs rather than status signaling

Some are now aiming to scale beyond niche online sales, exploring retail and funding to grow

But production, distribution, and market trust remain challenges, slowing broader expansion

At a lavish wedding in Dubai, guests including many from India arrived, dressed head to toe in pieces that speak of the finest international brands. On their wrists, the usual suspects—Patek Philippe, Rolex, Omega. Then walked in Jack Pace, a lawyer at a global law firm in New York. On his wrist was "Kakori 8 Down", a made-in-India watch, intended to strike a chord with his Indian clients.

His idea worked. The watch became an instant conversation starter.

"Kakori 8 Down", made by Mumbai-based Ajwain Watches, is based on the theme of a train robbery carried out by Indian revolutionaries in Kakori village near Lucknow in 1925. Pace was surprised that not enough people including Indians knew about the train robbery. "I found myself telling them the story...," he recalls, laughing warmly at the memory.

Another highlight of the piece was the elegant, yet sturdy, enamel dial—the base on which the hours, minutes and seconds are marked. Enamel dials, created by firing silica crystals mixed with metal oxides, are tricky to make as they often crack or form bubbles during firing. "When I touch a watch, I could tell someone worked incredibly hard to perfect the enamel dial. I know how easily they can crack," says Pace.

Finally, Pace was also surprised by the price: less than $400 (₹36,000). International brands with enamel work can cost over $1,106 (₹1 lakh) and go as high as $110,000 (₹1 crore).

A Seiko Presage Shippo costs $2,168 (₹1.96 lakh) and an Omega Seamaster Diver 300M costs $7,275 (₹6.6 lakh). Luxury models are even pricier. According to Chrono24, a marketplace for watches, limited edition pieces such as Jaeger-LeCoultre's Reverso Tribute Enamel Monet costs $154,927 (₹1.4 crore) and Patek Philippe's Calatrava Billiards 18K Rose Gold costs $409,450 (₹3.7 crore).

"People couldn't believe that a watch at that price had an enamel dial. It was so beautiful, and when I told them the cost, they were amazed that such a watch could be that affordable," Pace remembers.

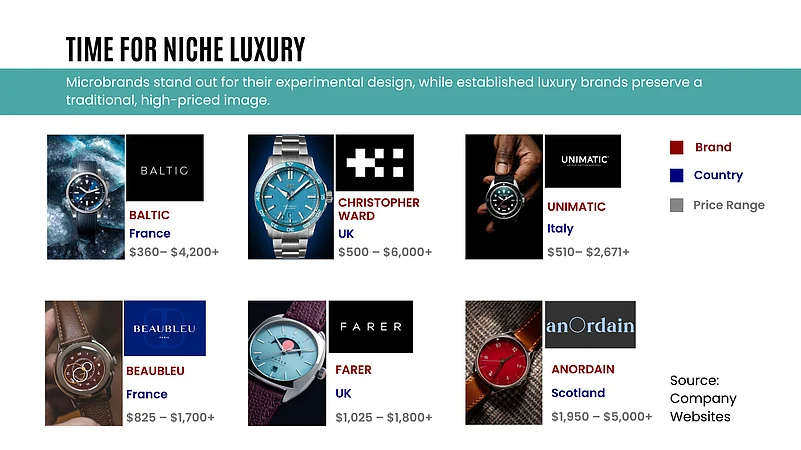

Pace is not the only collector who is looking for something different after spending years collecting timepieces from established brands and hearing the same stories. Many aficionados today are turning towards microbrands—small, independent companies that produce limited-edition products with a strong focus on design, authenticity and direct customer relationships.

"There's a growing interest not just in Swiss watches that start at $5,000 (₹4.5 lakh), but also in $400 microbrands that speak to you when it comes to the unique design and history," says Mexican watch collector Alejandro Rivas, who recently bought two watches: one from Ajwain Watches and another from Delhi Watch Company on his recent visit to Delhi.

One of the distinctive characteristics of microbrands is their willingness to experiment with design and storytelling, even as international established luxury brands maintain their traditional, high-price image. "Internationally, collectors are noticing that established brands are becoming more expensive while offering less, making these microbrands even more appealing," adds Rivas.

Many such brands have cropped up. They include French brand Baltic, which starts at $420 (₹38,000), and British watchmaker Christopher Ward, whose prices typically range from $500-$6,000 (₹45,000-₹5,40,000). Other international microbrands include Beaubleu, Farer, anOrdain and Unimatic.

The India Story

On November 25, 2025, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, hands folded and eyes fixed on the Ayodhya Ram Janmabhoomi flag hoisting, was seen wearing a $605.6 (₹55,000) Roman Baagh watch made by Jaipur Watch Company. The photographs, focused on his wrist, spread like a wildfire.

Perhaps reinforcing the Made-in-India narrative, the PM was again seen flaunting the watch—, adorned with a rare 1947 one-rupee coin—on several more occasions, including while flying kites on Makar Sankranti alongside German Chancellor Merz.

For Gaurav Mehta, Founder of the Jaipur Watch Company, this worked better than any advertisements or word-of-mouth. The month after the Janmbhoomi Flag hoisting saw demand for the particular watch rise so much that it continues to be in the waiting-list now. "We have sold almost 300 plus watches of that particular model in the last month. Currently, it is on a waiting-list of up to 55 days."

The incident is a reminder of the growing appetite for distinctive and elevated watches in India.

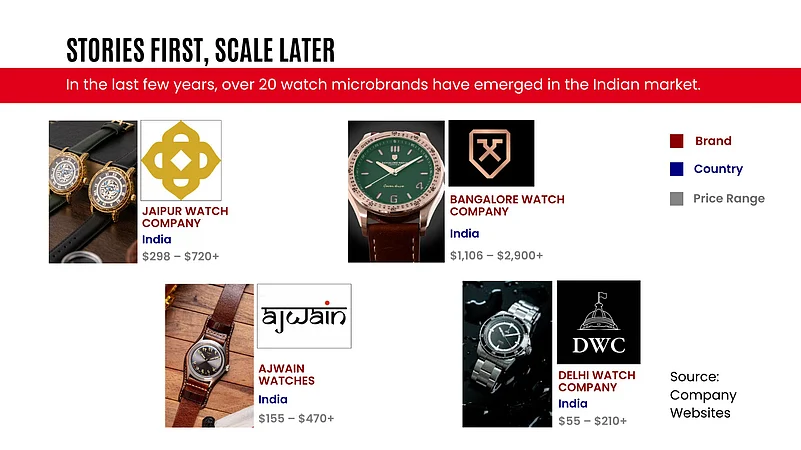

However, says Mehta, the Indian microbrand industry is still very small, estimating it at less than $16.5mn (₹150 crore), a tiny speck in the overall Indian watch market of $1.4bn (₹13,000 crore). But it’s growing fast, with more than 20 brands entering the space in just the last two years.

"When I started in 2013, there wasn't a second brand in the market till 2018…At this speed, the microbrand industry could reach $110.6mn (₹1,000 crore) within the next three years," he says. He is echoed by Sarosh Mody, director of Luxury Watch Works Pvt. Ltd, a Mumbai-based authorised after-sales partner for several global luxury brands. "I believe the shift toward a more globally aware younger consumer is creating new opportunities for microbrands, especially when product quality is matched with a strong narrative," Mody says.

Diverse Origins

Interestingly, most of these brands—such as Jaipur Watch Company, Ajwain Watches, Delhi Watch Company and Bangalore Watch Company—started as passion projects and often look towards India's culture and heritage for their inspiration.

JWC's watches, for example, often have a royal theme and draw heavily from India's regal past, incorporating elements such as Raja Ravi Varma paintings, vintage postage stamps and coins. The prices range from $298 (₹27,000) to $719 (₹65,000), with bespoke watches costing as much as $27,657 (₹25 lakh). Despite facing a rejection in Shark Tank India, Mehta has managed to raise a total investment of $519,934 (₹4.7 crore) from institutional and angel investors, according to Tracxn.

There are also others, such as Bengaluru-based techie couple Nirupesh Joshi and Mercy Amalraj, who have opted for more modern, but still quintessentially India, themes. In 2018, the couple left their high-paying jobs, and pooled their savings to start "Bangalore Watch Company" to tell India's story using motifs such as cricket, aviation and space through watches priced at $1,106 (₹1 lakh) and above.

"As we travelled to places like Boston, Hong Kong and Seoul, we developed a growing interest in watches. That's when the thought struck me. If international brands can be known for watches, why can't India?" says Joshi.

Joshi says that many customers of the Bangalore Watch Company already own Swiss watches, but they are looking for something more: "Someone in New York told us they bought our watch because it reminded them of playing gully cricket. Someone who grew up on the streets of Chennai said it brought back memories of Sachin Tendulkar playing at the Chepauk Stadium...This is an audience whose preferences have matured. They've reached a point where they've already owned several Swiss watches in their lives, and those no longer excite them."

Another example is that of Anish Dandwani, whose fascination with watches dates back to a childhood when he used to collect watches from Chandni Chowk's Ghadi Market. In 2020, he founded the Delhi Watch Company, which today sells over 23,000 watches a year with an average price point of $61 (₹5,500).

Meanwhile, Ajwain Watches' Vikram Narula is trying something different. The company is providing not only Indian themed watches but also the boxes made using wood, Banarasi saree, and patriotic leitmotifs.

Plans to Scale: Road Ahead

Having tasted initial success, many of these players are no longer willing to confine themselves to the niche, Indian, online market.

Jaipur Watch Company's Mehta, for instance, wants to open his first international store in Dubai by FY26, and scale the turnover to $11.06mn (₹100 crore) by FY28.

Joshi, of BWC, plans to open a physical location in Bengaluru soon. "It's an experience centre, not a store. We don't sell through third-party retailers…To truly experience the brand, you need to visit our flagship boutique," he says. "We may open one or two more stores in the next two years, but that's it."

To fund these, he is on the lookout for "patient capital" from family offices and individual investors willing to back him over the long term. "This is a decades-long commitment, not a short-term or years-long bet," he says.

Others are also thinking along similar lines, having spent the last several years experimenting with Indian storytelling.

Delhi Watch Company plans to open its first store in Delhi by the end of 2026. "It won't be a typical retail outlet. It'll be more of an experience centre," Dandwani says. He also has designs for a luxury line-up called "Quest" in the $774.38 to $7,743 (₹70,000 to ₹7 lakh) price range.

Ajwain Watches is willing to wait till it reaches a sufficient scale before it opens its first physical store. "Once we reach those volumes, we want to do something truly distinctive, similar to what Breguet has created in Geneva," says Vikram Narula, Founder of the Ajwain Watches.

Challenges

Meanwhile, these fledgling brands also face a unique set of challenges in scaling up. The first and most important obstacle is the lack of a watchmaking ecosystem, which manifests in various forms such as the lack of a mature supply chain and the poor availability of skilled workmen.

These limitations often constrain growth. The Bangalore Watch Company's plans for expansion, for example, are running into scaling challenges. It is in discussions with Dubai Watch Week, the world's largest watch exhibition, as well as one of the world's biggest watch retailers to take its watches to the GCC region.

"Opportunities like these will open up. But as I've mentioned, we're not demand-constrained, we're supply-constrained. If we partner with a retailer of that scale, we need to carefully plan how we'll meet their supply requirements," says Joshi.

Sarosh Mody of Luxury Watch Works highlights the skill gap in India. He says the art of making watches, or horology, is largely missing in India. A Swiss watchmaking course can set someone back by between $110,000-$165,000 (Rs 1-1.5 crore), beyond the reach of most.

He points out that the world needs close to 6,000 to 7,000 watchmakers a year. "Between the Swiss schools, the European schools and the US schools, I don't think they're able to surpass the 3,000 mark also. Who's going to fill the demand for the talent?" he asks.

Creating a Legacy

So, can the Indian microbrands really scale up to become a global phenomenon, or will they always be a niche segment catering to a home market with its select group of passionate customers and entrepreneurs?

Mody, for one, admits that Indian watchmakers, while comparable in sophistication with what other microbrands have to offer, have “a lot of catching up to do” when compared with the traditional luxury watchmakers.

Rajeev Asrani, Founder of Horpa Watch, points out Indian watchmakers cannot be compared to luxury Swiss or German brands that have built centuries of craftsmanship and global recognition. "Comparing Indian watchmaking directly to Switzerland is not realistic," Asrani says. "Twenty years ago, there was nothing; today, there's a beginning. In the next decade, we'll see significant change, and in twenty years, it will look completely different," he adds.

He does not want to speculate on how many decades it will take for Indian brands to achieve a level of global recognition comparable to that of Swiss or other brands.

"Honestly, it's hard to predict. It doesn't depend only on how well a brand performs, it's a far more complex equation. Trade policies, infrastructure, and several other factors all play a role. And given that it's a large country, outcomes can vary significantly from region to region and nation to nation," he says.

Arpit Verma, a watch aficionado and a brand consultant, puts it more bluntly: "We're nowhere close to competing with Swiss watchmaking, or even going head-to-head with Japanese brands (like Seiko)...That's hard to admit, especially as a strong supporter of indigenous products. For an Indian watch to earn a place in my collection, it has to evoke something unique, whether that's history, a story, or a compelling value proposition."

Whether Indian microbrands can truly break into the global mainstream remains to be seen. But for now, they've done something equally valuable: they've given collectors a reason to look beyond the usual suspects. And in an industry built on heritage and storytelling, that's no small feat.