Zero. Nada. None.

That’s the number of growth-stage start-ups (those who have reached Series B in funding) in artificial intelligence (AI) that are headquartered in India. It’s no surprise then that in the three years that have passed after ChatGPT took the world by storm, no Indian start-up is up to scratch in the generative AI race, much less be in the reckoning to win it.

When work on the inaugural Outlook Business Start-up Outperformers rankings began in late 2023, it had just been a year since generative AI had burst onto the scene. It was too early to have AI as a sector in the growth-stage rankings. Indian start-ups were just beginning to appear on the horizon of this new sector.

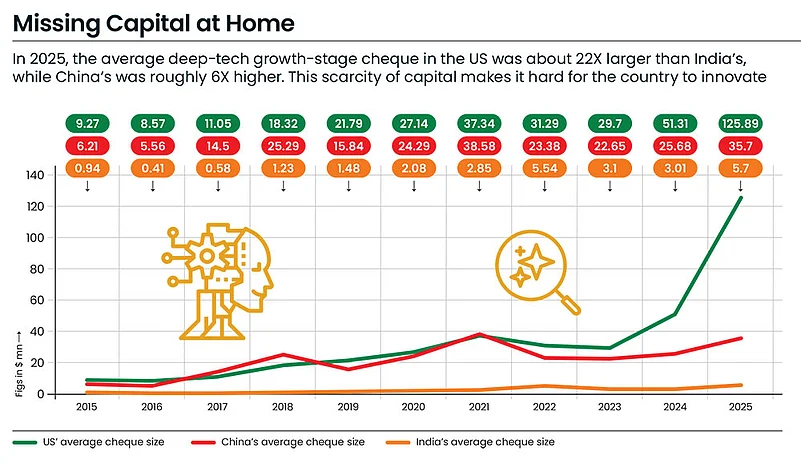

As another year passed by, the newsroom’s sentiment in 2024 was that perhaps a bit more time was needed for a capital-starved country like India to begin seeing AI start-ups cross the growth-stage hurdle. It was just in the US that dozens of AI start-ups were raising billions of dollars each and attracting millions of global users.

But when we began working on the latest edition of the rankings in late 2025, there was still not a single AI start-up based in the country that had raised a Series B round of funding.

Is something amiss? Industry insiders say the fundamental reason why India is lagging behind in AI is the lack of a culture of deep-tech innovation in the ecosystem.

"We are currently 'renters' of intelligence rather than 'owners’. We are heavily reliant on Western foundational models. This creates a significant gap in our ability to fully exploit the capabilities of AI,” says NR Narayana Murthy, founder, Infosys (see pg 28).

“To truly compete, we must pivot from building 'AI wrappers', which are essentially layers of code over someone else’s IP [intellectual property], to investing in deep tech," he adds.

Murthy’s diagnosis actually stands true for other sectors as well. Although India has scores of highly funded and even profit-making start-ups in sectors like fintech, consumer brands or software as a service (SaaS), none have yet been able to disrupt global markets with their innovation.

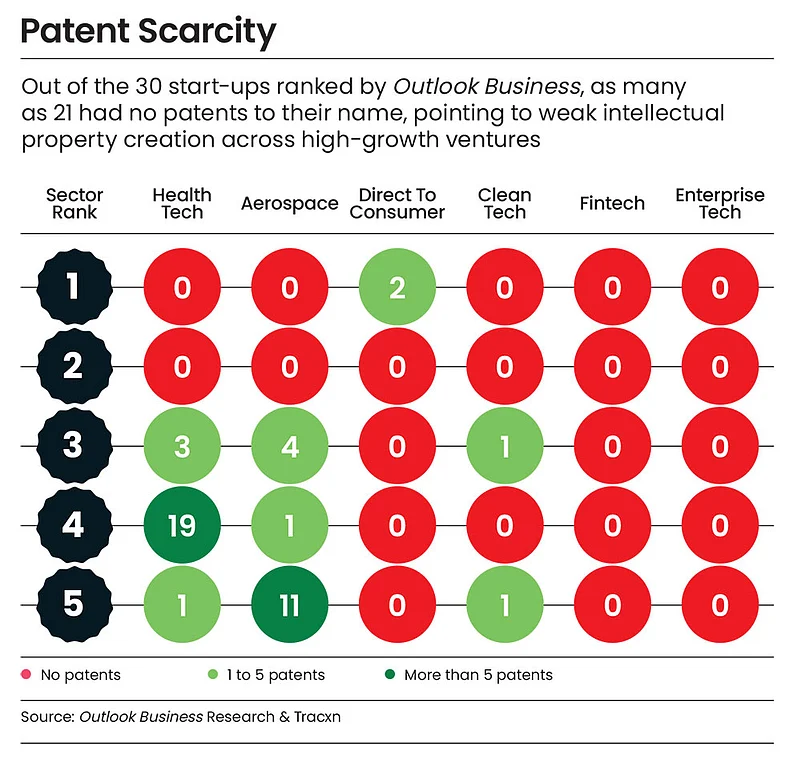

Here’s a troubling number based on our research: of the 30 start-ups across six sectors that have secured top rankings in Outlook Business Outperformers 2026, only nine have patents granted to them. None of the top five start-ups in fintech and SaaS have any patents. In the direct-to-consumer sector, only the start-up in pole position has patents to its name.

“Low patenting and the absence of growth-stage AI start-ups are not accidents; they are the result of an ecosystem that rewards speed, services and early monetisation over deep research, risk and IP ownership,” says Payal Arora, professor of Inclusive AI Cultures at Utrecht University and co-founder of InclusiveAI Lab.

Numbers Don’t Lie

At a congregation of the country’s start-up founders and investors in April last year, Union minister Piyush Goyal ruffled feathers with his stinging remarks on the Indian ecosystem being focussed on 10-minute delivery apps and ice-cream start-ups.

Although he partially conceded recently that his evaluation of the start-up ecosystem may not have been entirely accurate, the numbers support his initial thesis. As of August 2025, India is home to around 5,700 deep-tech start-ups, far fewer than the 26,000-plus in the US and about 6,400 in China.

Growth-stage investment in deep-tech start-ups fell from $888mn in 2023 to $767mn in 2025. The number of deals declined as well, from 61 to 53

More importantly, the two global powers are today home to a vintage of older and more mature deep-tech start-ups. As many as 43% and 45% of the current deep-tech start-ups in the US and China, respectively, were founded before 2015. In India, by comparison, only 24% of deep-tech start-ups were operational a decade ago, according to data platform Tracxn.

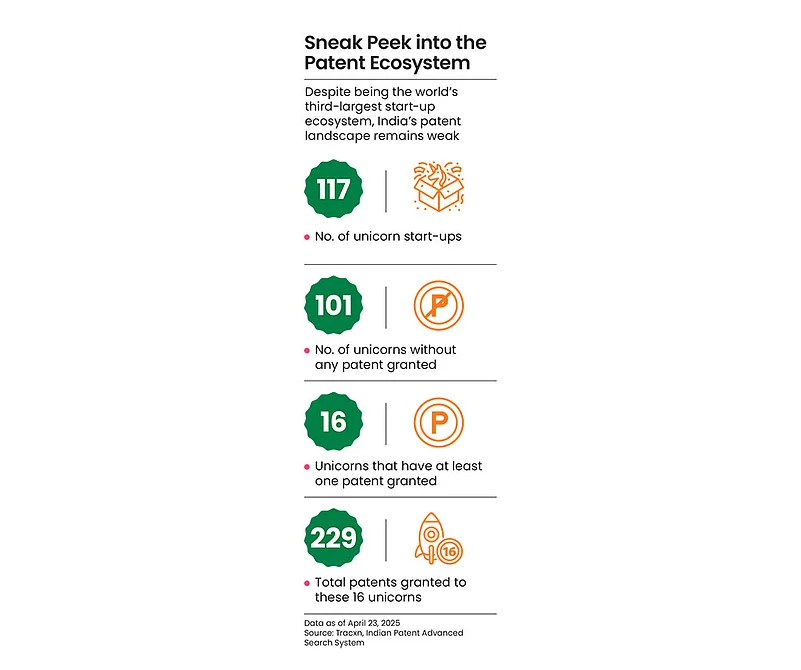

Another concerning fact is that India’s most celebrated start-ups—its unicorns—have very little innovation to brag about.

An evaluation of patent filing data by Outlook Business last year showed that of the country’s 117 unicorns, 101 did not hold any patents at all.

In aggregate, Indian unicorns own only 229 patents. Nearly two-thirds of these are concentrated in just two electric vehicle (EV) companies—Ola Electric and Ather Energy—according to Indian Patent Advanced Search (IPAS) System data as of April 2025. Ola Electric tops the list with 99 patents, followed by Ather Energy with 46, together accounting for the bulk of patent ownership within the unicorn cohort.

The malaise runs deeper. It’s not just the shiny new billion-dollar start-ups that are ignoring deep tech. India Inc consistently spends less than 1% of its annual revenue on R&D, even though the industry’s profits pile up as cash on its balance sheets.

“People say they don’t have money to invest in R&D. That’s not true...If you look at the top 500 companies in the country, they have enough cash. But how many of them are actually investing that cash into R&D," asks Swapnil Jain, co-founder and chief technology officer of Ather Energy (see pg 84).

For instance, the country’s information-technology (IT) majors aren’t keen on building large language models or proprietary software applications. The focus is on maximising quarterly profits and paying dividends. According to industry estimates, Indian IT services companies already generate approximately $20bn in free cash flow annually and more than 75% of that is returned to shareholders.

Meanwhile, data shows that revenue growth has largely slowed down as clients in the US and Europe are rethinking IT outsourcing expenditure amid the AI boom.

Ajay Chowdhury, co-founder of IT firm Hindustan Computers says that corporate decision-making at the board level is often driven by return on investment (RoI) measured through immediate profits.

“Few boards are willing to evaluate RoI that may materialise five years down the line. Innovation, however, typically delivers results only over a three- to five-year horizon,” he adds.

Capital Conundrum

When IIT Delhi alumnus Prateek Sachan began building Bolna, a voice-AI start-up, two years ago, the beginning was painful. Pitch meetings with venture-capital (VC) investors were frequently cursory. Some investors joined late, took calls from their cars, or glanced at phones mid-conversation. Many struggled to grasp the product at all.

Follow-ups promised within 24 hours rarely came. In one memorable meeting, after an hour-long discussion, an investor’s closing question was disarmingly basic: did the company use APIs? Application programming interfaces are software bridges that connect different platforms.

“We watched capital flow to ‘famous and veteran names’. VC analysts were tasked with running weekly podcasts with founders. Those podcasts have quietly stopped now. No surprises there. We received unsolicited advice from ‘founder-friendly VCs’ to shut down,” he rues in a LinkedIn post.

Founders argue that VCs in India are designed for speed, predictable revenue curves and returns that can be quickly explained to limited partners. New age consumer brands, fintech, SaaS and quick-commerce platforms fit the venture playbook far more neatly. Deep tech, by contrast, operates on a very different clock, often requiring seven to 10 years before commercial results begin to show.

“Quick commerce, for example, is very easy for investors to understand. It is asset-light, it scales fast and it is purely execution-driven. You don’t need factories, you don’t need machinery, you don’t need years of R&D. You just need people, laptops and software,” argues Arvind Sethi, founder of Bengaluru-based deep-tech start-up Dual Safe.

For deep-tech start-ups, however, the early years are not the hardest. Initial capital often comes through government grants, seed funds or limited institutional support.

But the real test arrives at the growth stage.

If start-ups, investors and large companies in India don’t make long-term efforts to create IP, they will be at risk of getting their margins hit

Suchin Jain knows this well. Over seven years, the founder of iPanelKlean, a start-up with patented technology in the solar-energy sector, invested nearly ₹5 crore of his own capital and pieced together small cheques from grants and seed funds. Now, he is finding it extremely difficult to secure a growth-stage round of ₹17–18 crore to scale the company.

He is not an exception.

Growth-stage investment in deep-tech start-ups fell from $888mn in 2023 to $767mn in 2025, according to data from Venture Intelligence, a data platform. The number of deals declined as well, from 61 to 53.

For the Long Haul

When Union minister Goyal criticised the start-up ecosystem last year, he made an important point beyond all the rhetoric. When India enters agreements with other countries, it is expected to showcase its best start-ups. “I cannot take them to grocery stores and say this is India’s offering,” he said.

At a time when the global order of yore is in a state of flux and trade pacts are being redrawn, nations without advanced technologies can’t make a good bargain. As India has struggled to reach a trade deal with the US over the past year, many experts have pointed out this weakness.

“We’ve been comfortable with a rent-seeking approach—making money from what we already have—partly because we weren’t challenged globally to that extent earlier,” contends Jain of Ather Energy.

But that approach won’t work anymore. If Indian start-ups, investors and large corporations don’t make long-term efforts to create IPs, they will be at risk.

At first, their margins will take a hit as the likes of the US and China become more extractive in their tariff regimes. And subsequently a day will come when critical raw materials and technologies will be blocked. This is already playing out in AI chips and EVs.

As the prime minister reportedly told 12 of India’s most-promising AI companies last month in a closed-door meeting, they can’t be building “toys”. The country needs them to step up. It’s high time.