Eli Lilly’s weight-loss drug Mounjaro became India’s top-selling medicine by value in October

With Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide (Wegovy) patent expiring in March 2026, the market is expected to be flooded with cheaper generic alternatives

The promotion and advertisements of prescription drugs under Schedule H1 are banned under Indian law

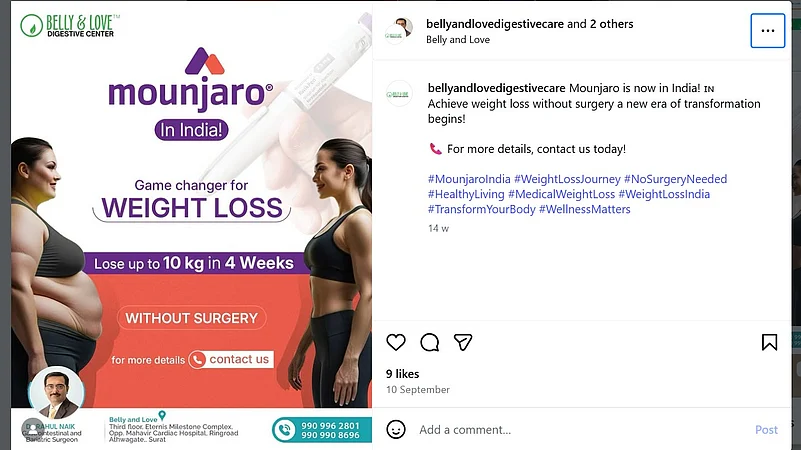

Social media posts by influencers claiming to be doctors are promoting weight-loss drugs such as Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro and Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy, even though they fall under a class of medicines that cannot be advertised under Indian law, according to lawyers and consumer and health activists.

Outlook Business has reviewed several posts of weight-loss drugs being promoted on social media platforms, some of which share ‘before-and-after’ transformation photographs of patients. Legal experts say physicians are permitted to educate patients about these drugs, but not to advertise them.

Several of these medications entered the Indian market in 2025 and are no longer out of reach for middle and upper income groups. Doctors say interest spans age groups from teenagers to older adults.

Weight-loss drugs work by increasing satiety and curbing appetite, leading to reduced food intake and weight loss.

According to a Reuters report quoting Pharmarack, Eli Lilly’s weight-loss drug Mounjaro became India’s top-selling medicine by value in October. By volume, its consumption was 10 times that of rival Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy in October, with Lilly selling 262,000 doses versus 26,000 for Wegovy. The report mentioned that the weight-loss market in India would generate $150 billion by the end of the decade.

A March 2025 Pharmarack report mentions the anti-obesity drug market has quadrupled in the last 5 years. The report says, “While several molecules are available in the anti-obesity market, it is semaglutide from Novo that has propelled the growth of this market and tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is also expected to push this growth further.”

Prohibited Promotions

According to lawyers and activists, the promotion and advertisements of such drugs are banned under Indian law. They point out that while over-the-counter drugs such as paracetamol and crocin can be promoted, there is a ban on promoting prescription medicines, such as weight-loss drugs classified under Schedule H1, under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 and the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, 1945.

“Any promotion of such medicines, including on social media, is banned to prevent self-medication and misuse. The marketing of new prescription weight-loss drugs such as semaglutide (Ozempic) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is strictly regulated and, without prior approval from the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO), is largely illegal in India,” says Salman Waris, Managing Partner at TechLegis Advocates & Solicitor. “Promoting such drugs via social media…can result in fines up to Rs 5 lakh, license revocation, or imprisonment,” he adds.

However, the law only covers direct promotion of these drugs and surrogate or indirect advertisements fall outside its scope.

In response to a query by Outlook Business, Novo Nordisk said any social media content developed or sponsored by the company is identified and labelled with all applicable laws, disclaimers, and regulations. "We provide comprehensive training and information about our products while detailing the healthcare professionals. This includes information around the specific indication, suitable patient population, dosing, administration, and follow-up."

However, the company said, they cannot comment on the posts or opinions of individuals on social media.

Increased Queries

Under the Endocrine Society of India (ESI) updated guidelines on obesity in India, these drugs may be prescribed to individuals with a body mass index (BMI) above 30, or those with a BMI above 27 if they have obesity-related conditions such as diabetes, hypertension or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

However, with increased social media promotions, the queries from people who are not even obese have increased, ethical medical practitioners tell Outlook Business.

“I receive many queries from people who are not obese but merely overweight. These people do not medically qualify for the treatment, and I have to refuse them,” says Dr Arjita K Kumar, consultant physician and diabetologist at Polaris Hospital, Gurugram.

“Once, a girl who weighed 65-kg asked for weight-loss injections, and I had to counsel her to regulate her diet and that she did not require medication,” Dr Arjita narrates.

She points out that many of her patients get to know about these drugs from social media. “I can say 10–15% of my patients come solely because of what they’ve seen on social media platforms, where many doctors and dieticians are blatantly promoting these drugs,” says Dr Arjita who has treated almost 70 patients with obesity.

“This is the age of social media and hyper-connectedness,” says Dr Aparna Govil Bhasker, bariatric and laparoscopic surgeon at Saifee, LH Hiranandani, Namaha and Apollo Hospitals in Mumbai. “People have access to information almost instantly. It is encouraging that they bring their questions to doctors, because that allows us to guide them accurately and responsibly.”

Passive Advertisements?

In a Novo Nordisk advertisement on Instagram, an obese woman is shown dancing and gasping for breath. The ad does not mention the medicine by name; instead, it includes a prompt encouraging viewers to learn more from their doctor and a “Book Now” icon.

Lawyers say that such advertisements do not violate existing laws. Arjun Bhagi, Partner, Khaitan & Co. explains these advertisements are indirect, similar to how banned products like alcohol are promoted. Instead of naming the drug, they talk broadly about obesity as a disease and suggest that solutions exist.

“The ads hint at treatment without mentioning the product, prompting viewers to consult their doctors. This approach is meant to start a conversation rather than directly sell the medicine and is often described as passive advertising, amplified through heavy media presence,” says Bhagi.

Novo Nordisk said their public disease awareness campaigns are designed to bring a positive change in society. "Like any type of bias and discrimination, excess weight can have a significant impact on people’s mental health. It could lead to anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. It is important to acknowledge this and also remember that excess weight is not a reflection of individual failure," the company mentioned in the note.

"Our objective is to address the larger societal problem that demands collective action. Through our campaign, we aim to encourage action towards creating a society where everyone, regardless of their weight, feels valued and empowered to live their best life," it added.

Why Regulation Matters

Doctors stress that obesity should be treated as a medical condition, not a cosmetic concern, as the drugs can cause side effects ranging from nausea and diarrhoea to serious risks such as pancreatitis and thyroid cancer. Ethical practitioners counsel patients thoroughly and monitor them closely, while refraining from promoting the drugs publicly.

Waris says, like any other medication, these drugs are not one-size-fits-all. Individuals may have underlying conditions that can lead to adverse reactions. “The primary purpose of regulation is to protect the public from such risks, which is why these medicines are classified as scheduled drugs and are subject to strict regulatory control,” he says.

Bhagi says: “Anything superficial does not affect the physiological state of the body: That’s cosmetics. This (weight-loss drug), however, is a drug: a proper, scalable drug. It’s being positioned as a cosmetic, but in reality it’s a formula designed to control hormones. Its physiological impact is significant and can cause side effects. These side effects are what have been marketed in India."

Affordability + Promotion: A Dangerous Combination

The situation has been made more complicated as drugs like Wegovy have recently become more affordable, and queries now come from people of all income levels, says Dr Aparna. “The starting dose now costs around ₹10,000 per month. As the dosage is increased, the cost can rise to approximately ₹15,000–16,000 per month,” she says.

Other popular anti-obesity/diabetes drugs include Rybelsus, Trulicity and Aplevant. These medications are prescribed by doctors based on a patient’s physiological condition, with careful consideration of potential side effects and individual suitability. For Mounjaro, monthly costs typically range from about ₹14,000 to ₹25,000, depending on the prescribed dose.

These are long-term medications and cannot be prescribed for just two or three months.

All trials conducted of these weight-loss drugs have had a minimum duration of 72 weeks, says Dr Aparna. “At a monthly cost of ₹15,000-25,000, the total expense over a year can amount to ₹3–4 lakh or more,” she explains.

With Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide (Wegovy) patent expiring in March 2026, the market is expected to be flooded with cheaper generic alternatives. Hence, misinformation and promotion of these drugs need to be curbed, experts explain.

Lack of enforcement

There are laws and regulations, but like in many other areas, the problem lies in enforcement.

The Advertising Standards Council of India has not taken up cases of direct promotional advertisements for drugs prohibited from advertising. However, its consumer complaints division has in the past upheld multiple complaints against slimming clinics and products for making unsubstantiated claims, including implications of guaranteed or rapid weight loss.

The advertising industry’s self-regulatory body, which has processed 41 weight loss and slimming advertisements between April 2022 and September 2025, said it will continue to track and monitor such content.

Consumer activists contend that these ads fuel insecurity among obese and overweight individuals and contribute to fat-shaming. Jehangir Gai, an award-winning consumer activist, points out that many public interest cases on the subject are pending in courts.

“The promotion of these drugs also induces an insecurity in people on top of making them yearn for these drugs, only to leave them stranded with more health problems,” Gai says. He dismisses the argument that such content is difficult to monitor on social media.

“Social media operates on algorithms. The moment certain keywords or content are detected, a post can be automatically flagged and taken down. There are countless algorithms already designed to push sales. So if I were to post something new, explicit, or even fake, wouldn’t it be removed automatically without any manual intervention?,” argues Gai. “The system is clearly capable of identifying and pulling down such content. The problem is that the government is not applying the same level of vigilance here,” he says.

The good news is the government has not completely turned a blind eye. Bhagi shares that during a meeting held in November 2025, the Drugs Consultative Committee (DCC), the statutory advisory body established under the Indian Drugs and Cosmetics Act, expressed concerns regarding the unregulated promotion of potent drugs across digital platforms.

During the meeting, DCC noted that the existing drug-license conditions already prohibit manufacturers from advertising medicines listed under Schedules H, H1 and X.

However, Bhagi says, these restrictions, while applicable to manufacturers, do not explicitly extend to licensees involved in the sale or distribution of these drugs. This creates a loophole that marketers have been exploiting. While DCC recommended introducing similar restrictions for sale or distribution, no corresponding provision or amendment has been notified as of now.

“While we have strong laws, enforcement remains a major challenge, especially with the rise of social media and digital platforms…the digital ecosystem has made it far more complex,” says Waris.

A comparable example is online gaming. It began with claims that it wasn’t about money or gambling, and for a long time the government largely looked the other way. Over time, it effectively became normalized, until it was suddenly treated as a national security issue and banned almost overnight. Lawyers and activists believe such strict enforcement may be applied to the promotion of healthcare products soon.