Deepfake video of FM Sitharaman triggers legal and policy alarm

Multiple laws cover digital deception, but enforcement remains patchy

Platforms like Meta may face liability under IT Act if found negligent

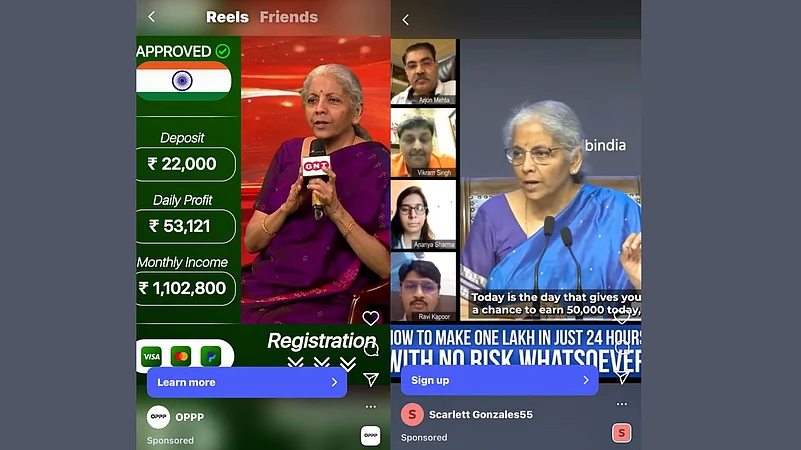

After a deepfake video of Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman touting a scheme to triple investments went viral recently, the government’s fact-check unit flagged it as a scam.

But this wasn’t an isolated incident.

Over the past few days, Outlook Business has found nearly a dozen similar videos still floating around on Meta-owned Instagram. Most of these videos are tagged as sponsored content, implying that the tech giant is making money on these posts.

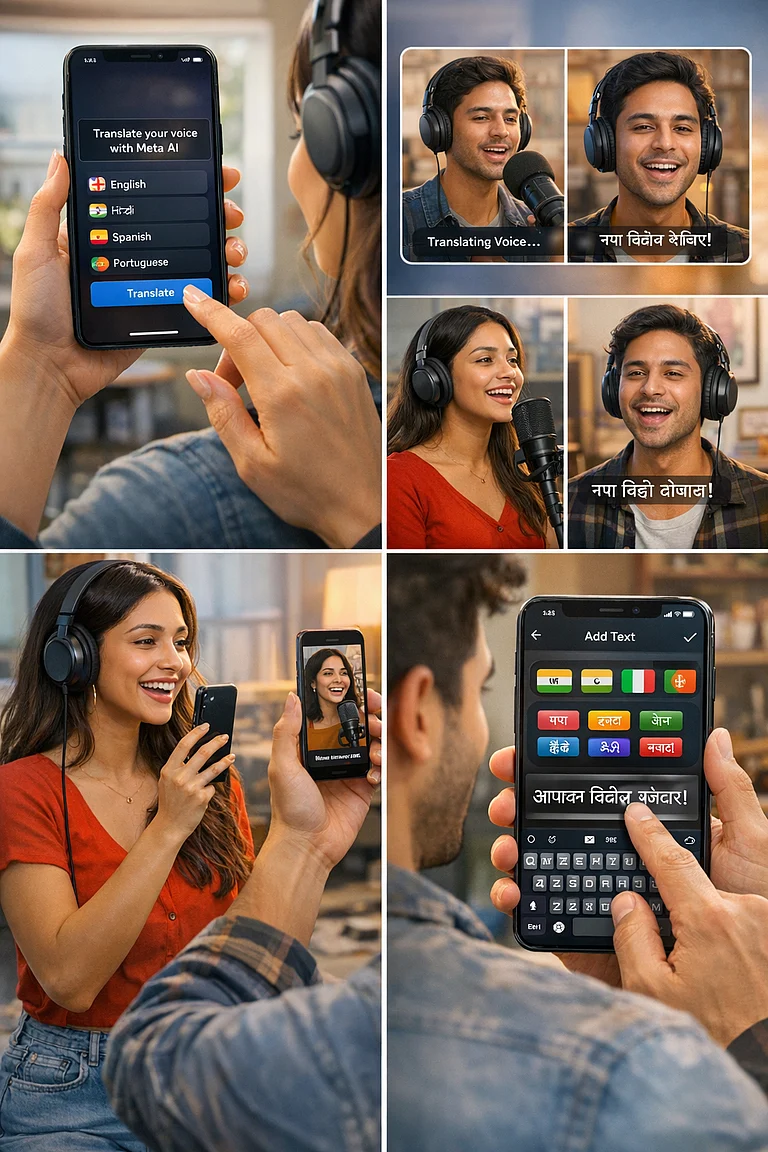

This comes after Meta decided earlier this year to reduce the moderation of content by human reviewers — and rely more on automation for such work.

“Tech giants like Meta earn big from India’s huge user base and ad revenue, but they often fall short of acting responsibly towards the India market when it comes to deepfake circulations due to various inherent factors. Some of these lapses stem from practical challenges, while in other cases, they exploit the grey areas in the regulatory landscape,” said Salman Waris, founder of law firm TechLegis.

He says that advertisers pay for reach, and platforms’ algorithms prioritise engagement—sometimes at the cost of deeper ad scrutiny.

While the tech giant is saving costs by automating content moderation, it is making more money than ever. In India, which is Meta’s biggest market in terms of user base, with over 500 million people using its platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp, the cost per 1,000 impressions for online content can be as low as ₹7-10, according to industry experts.

According to reports, Meta’s total revenue from India has jumped approximately 15-fold over the past four years from ₹1,485 crore in FY21 to ₹22,730 crore in FY24. The big tech’s net profit from India has also surged nearly four-fold from ₹128 crore in FY21 to ₹504.93 crore in FY24.

Meanwhile, the tech giant has been at the centre of controversies regarding deepfake content on its platforms, including a doctored video of Union Home Minister Amit Shah during the 2024 elections.

At a public forum earlier this week, FM Sitharaman said, “The same tools that power information can be weaponised for deception and fraud. I am not personalising it but I can say I have seen several deepfake videos of myself being circulated online, manipulated to mislead citizens.”

Outlook Business reached out to Meta with queries on the matter. “We have enforced against the ad for violating our policies,” the company said.

Rule of Law

Although incidents related to deepfakes, fake investment advisories, misleading social media ads, and impersonating public figures are not dealt with under a single law, they are addressed by numerous rules and regulations designed to protect consumers.

When it comes to ads and promotions, Waris highlights that the Consumer Protection Act, 2019, plays a significant role. It prohibits misleading advertisements and empowers the Central Consumer Protection Authority (CCPA) to act against false or deceptive ads, including those by social media influencers. Violations may lead to heavy fines and criminal penalties.

Apart from CCPA, there is the Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) that regulates ad standards, including monitoring and taking action on a deepfake or unauthorised use of public figures. In addition, the government has recently introduced the Digital Advertisement Policy, 2023, that empower government agencies to regulate digital ads and enhance accountability on social media platforms.

While the IT (Intermediary Guidelines) Rules, 2023, also require platforms to exercise due diligence, moderate content, and maintain grievance redressal, it is Sebi’s responsibility to give mandates for registration and verification for entities running financial ads to curb misleading investment advice.

The creation of such videos with the intent to mislead the public and cause financial loss may even invoke provisions of the BNS, 2023, including Sections 318 and 319 (cheating by impersonation), Sections 335 and 336 (creating false electronic records), and Section 340 (using electronics as genuine), according to Kapil Arora, Partner, Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas.

And if the crime is committed to obtain financial benefit, Arora says that Section 111 and Section 66D of the IT Act, 2000, which penalise cheating by impersonation using computer resources.

Platforms on the Hook

Arora reveals that platforms like Instagram or its parent company, Meta, can be held liable under Section 79 of the IT Act if they fail to remove such content after being flagged or receiving any government or judicial order.

Under Section 79 of the IT Act, intermediaries are protected from liability only if they act swiftly upon receiving information about harmful or unlawful content.

“Once a platform is notified, it has a statutory obligation to remove or block the content. Failure to do so can make it complicit under the law,” says Rohit Kumar, founding partner at the public policy firm, The Quantum Hub.

However, it is not known if the government has issued directives or taken any legal action to have the Sitharaman deepfakes taken down from the social media platform. Outlook Business has sent queries to the Finance Ministry, RBI, and Sebi on the matter. They have not responded to the queries till the time of publishing the story.

Several cases of deepfake videos have surfaced repeatedly over the past few years. Even last year, a fake video of former RBI governor Shaktikanta Das and FM Sitharaman promoting the government’s ‘income-generating platform’ also came to light.

Fraud Detection Limits

As fraudsters use AI to create deceptive videos, another bunch of artificial intelligence tools is being deployed to sniff out the fakes. “AI-based detection tools are increasingly used to catch deepfakes and unauthorised use of likenesses, but challenges remain due to evolving tactics like short videos, memes, and new fraudulent content formats,” says Waris.

He recommends that platforms need to keep robust content moderation and complaint systems to quickly take down fraudulent ads and suspend repeat offenders. However, gaps still persist, especially, for organic content or posts that evade paid ad checks, leaving users vulnerable to scams.

Waris says that India’s laws are evolving but lack strong teeth or fast action to force platforms’ full accountability. Additionally, cross-border data and operations slow down Indian regulators’ grip on foreign tech firms.

Kumar adds that when it comes to deepfakes or impersonations, the tech isn’t quite there yet. In other cases, technical measures like the nudify filters are used to detect issues like objectionable or misleading content.

“Companies usually rely on a mix of automated detection and human moderation. Either technology flags something for review, or a small percentage of ads are manually checked to identify patterns and improve detection. But it’s unrealistic to expect every uploaded ad to be manually reviewed,” he adds.

According to him, likeness detection is complex because moderators across geographies might not easily recognise who’s being impersonated. He suggests that users should flag such content immediately to the social media platforms, so that it can be taken down faster. “If a certain number of users flag an ad as fake or impersonation, it should automatically trigger a manual review and slow the ad’s visibility until verified”.

Call for Stronger Rules Ahead

As technology grows, so does the misuse. Even with laws in place, fraudsters continue to find new cracks to slip through. Hence, Waris called for deepfake-specific laws, which can define and criminalise the use of AI-generated content for fraudulent advertising, combined with technical standards for detection.

In addition, there should be a focused agency or data protection board with the power to investigate, penalise, and proactively monitor social media ads for misleading content. Clear user reporting mechanisms and transparency on advertiser identities and ad origins can also help curb fraud.

“Regulations must cover not just paid ads but also promotional content shared organically by influencers or pages. Platforms should have live, automated systems to verify advertiser credentials (e.g., SEBI registration) continuously,” he adds.

Shravanth Shanker, a Supreme Court advocate, points out that India’s legal system has begun addressing deepfake-related crimes through civil and criminal remedies, although specific legislation targeting deepfakes remains pending.

In September and October 2025, the Delhi High Court granted interim relief to actress Aishwarya Rai Bachchan, banning the creation and circulation of deepfakes and AI-generated content that exploits her identity. The court said that using her persona for deepfakes and AI-generated content violates her personality rights.

These rulings are important because they show courts are willing to hold social media platforms partly responsible if they host or fail to promptly remove such content. In other words, the cases create an early legal precedent that platforms can be made liable for enabling or ignoring fraudulent AI-generated videos and impersonations.

The limits of detection are both technological and operational. While India has a growing framework addressing misleading and fraudulent ads on digital platforms, new challenges like deepfake misuse and unregulated influencers require stronger enforcement, real-time tech tools, and wider regulatory reach to protect consumers effectively.