There are people with a gift for apt metaphors, and then there is Anant Gawande. During the Q3FY18 earnings call, the director of Talwalkars said, “If there was a joint, which makes vada pao then it should make only vada pao and nothing else.” Gawande was trying to explain Talwalkars Better Value Fitness’ (TBVF) strategy to demerge its business into two entities — TBVF and Talwalkar Healthclubs (TH). But if you are a fitness chain, you should stay a few miles and rhetorical flourishes away from fast food.

Today, when Talwalkars has been dragged down by its unhealthy appetite for debt, Gawande’s metaphor seems unfortunate. There was one, too many vadas, and worse, the books allegedly were overcooked. Despite repeated attempts to schedule a meeting and Outlook Business sending a detailed questionnaire about the goings-on, the company refused to respond.

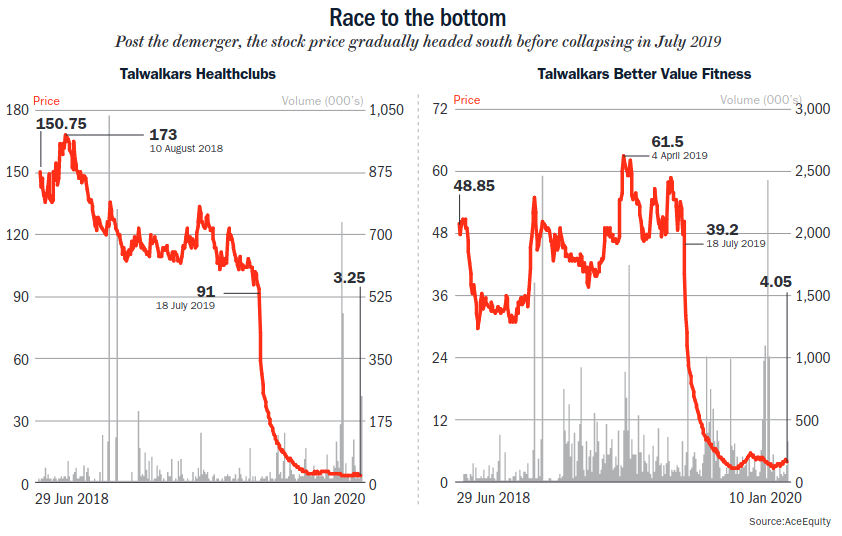

At its peak, in March 2015, the stock price of the combined entity was Rs.410. The downward movement began a year later, when the demerger plan was announced. Cracks in its operations began to show when numbers for both businesses — the high-end health-club business (TBVF) and the more lucrative gym vertical (TH) — were reported separately. After the demerger was effected on June 29, 2018, a concealed debt pile came to light. The stock price has since cratered — TBVF fell from a high of Rs.65 in April 2019 to Rs.4.05 in January 2020; and TH from a high of Rs.173 in August 2018 to Rs.3.38 in January 2020 (See: Race to the bottom).

The once marquee gym brand has been reduced to a fraction of its past glory. Last October, rating agencies downgraded the stock to ‘D’, which means the ‘company is in default or is expected to default on maturity’. It is a long fall for a company that pioneered a fitness trend in the country.

‘Debtlifting’

Its history dates to 1932, when Vishnu Talwalkar in his twenties set up the first centre at Mumbai’s Linking Road. Then it was called Ramkrishna Physical Culture Institute. The founder (grandfather of the present director of TBVF, Prashant Talwalkar) was a wrestler, who had worked in a vyayamshala part-time, before starting out on his own. He would go home-to-home to train those interested and even encouraged women to come to the centres. Fitness could now be pursued as a family, and in 1962, his son Madhukar opened the Talwalkars Gymnasium in Bandra. In the eighties, the third generation — Prashant and Girish — joined the firm and, in early 2000s, Anand Gawande and Harsha Bhatkal came on board, later being appointed as whole-time directors in 2009.

The five took the brand to other cities and diversified its services beyond gym to include spas, aerobics and health counseling, all a novelty at the time. It also began acquiring companies or entering into joint ventures and franchisee agreements. By FY09, they had 35 gyms. Growth had largely been funded by financial institutions and renowned investors such as Shivanand Mankekar, who invested about Rs.35 million in 2006.

In 2010, the ambitious TBVF went public. The IPO was oversubscribed 28x in the Rs.123-128 price band. After listing at Rs.138, the stock closed at Rs.162 on May 14. By then their number of gyms (now called healthclubs) had increased to 51, most of them promoter-owned, and they were spread across 24 cities in 11 states. An analyst who tracked the company since its listing says that Talwalkars “was growing at 18-20% year-on-year post listing and had a healthy balance sheet”. Currently, the company operates 251 fitness centres across India and Sri Lanka, and has presence in six South East Asian countries.

All seemed to be going well. Only, the company was growing on heavy borrowing, which far outweighed its assets. An analyst points out that during the IPO, the company had claimed that its expansion would be done through an asset-light model with minimal capex and loans. The truth was far from that. In FY16, TBVF’s debt reached Rs.3.62 billion, when its revenue was Rs.2.51 billion and net profit Rs.553.7 million.

The management gave an explanation. They said the loan was taken to acquire the Sri Lankan gym and for other tie-ups, and that it was temporary. “They said there was a cash flow mismatch since they hadn’t earned much cash that financial year. And that the next year, whatever cash they generate will be used to fund expansion,” says Abhishek Agarwal, assistant vice president-equity research, Prithvi Finmart. But cash flow dropped substantially in FY17 to Rs.27.9 million from Rs.281 million in FY16.

Even in October 2018, the company was trying to raise NCDs to the tune of Rs.5 billion and sought another approval for investment, loans and guarantees, up to Rs.5 billion. Simply put, they wanted approval to raise a loan for repayment of debt and then another approval to invest the same amount elsewhere. The two resolutions gave contradictory information, noted a report by Stakeholders Empowerment Services (SES). “We had recommended voting against both resolutions because at the time, the company had total assets of Rs.4.19 billion. Raising a debt of Rs.5 billion on this is like a 40 kg person trying to lift a 400 kg person,” says JN Gupta, MD, SES. Net debt increased by 44% in the period from FY18 to FY19, according to Brickwork Ratings. Reportedly in FY19, Talwalkars Group had net debt of around Rs.7.19 billion against Rs.1.39 billion in cash and investments.

To be fair, all players in the fitness industry are incurring losses. Cure.fit, founded by former Flipkart executives Mukesh Bansal and Ankit Nagori in 2016, is still in the red. It earned revenue of Rs.346 million and lost Rs.986 million in FY18. In FY17, it posted net sales of Rs.30 million against loss of Rs.179.8 million. But Talwalkars comes under closer scrutiny for being the only listed player.

By 2017, analysts had begun to sense something was not right at the fitness hub. Agarwal says that the management kept reporting revenue and profit figures, and saying that the cash flow was being used to fund expansion. “But the truth is they were expanding with loans. There were no internal accruals,” he says. Analysts also blame the auditors Lakdawala and Associates and MK Dandeker & Co for not flagging the “fudged” revenue and profit figures. Dandekar & Co resigned in August 2019 citing company’s inability to provide satisfactory responses to queries.

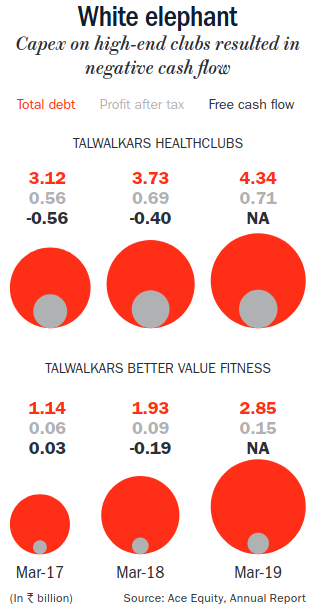

A senior fund manager states that a company reporting an ebitda margin in the range of 40-65% over the years should have been able to fund its expansion through internal accruals. “But the company wasn’t generating the kind of profit that was being reported. The numbers were substantially exaggerated through accounting gimmicks. That’s why they were not generating enough cash flow.” As the share price tanked, BSE sought a clarification on July 18, 2019. In response, all the company said was, “we are not aware of any information and/or event which may have caused such downward movement….” By then, cash flow had dropped precipitously and debt had risen to alarming levels (See: White elephant).

The earlier mentioned fund manager cuts to the chase: “Talwalkars is not a business problem. It is a governance problem… The promoters have clearly fudged revenue and profit numbers. As a result, investors have already lost their entire equity value and very soon debt holders are going to lose value. People have to write-off a large part of the debt that they have given.” Lenders to Talwalkars Group include Lakshmi Vilas Bank, Axis Bank, South Indian Bank and Indian Bank.

Shriram Subramanian, MD, InGovern says that the company has been “defrauding” investors. “It has been reporting positive operating margins in their ‘audited’ results. So investors, till the very last moment, believed all the numbers to be true.” The same thing happened at Manpasand Beverages and Sintex too, he adds. At Talwalkars, analysts say, the management used “accounting gimmicks” such as showing operating expenditure as capital expenditure and “non-disclosure” of various details such as cost of acquisition of assets made outside India, licence agreements and the revenue model for the demerged entity.

Later, piecing together the puzzle, analysts found that the company’s aggressive expansion into the club business was what broke its back. It is a high-capex and low-return business, when compared to gyms. Industry estimates peg the average investment required to set up a gym at Rs.30-40 million, while a club requires close to Rs.750 million. “But the gym business delivers RoCE of 15-18% while club business generates low single-digit return. The company thus made the wrong move by investing heavily in the club business,” says an analyst. Care Ratings, in its July 2019 note, states that most of the debt raised was to invest in higher-end ventures such as ‘Sarva’ and the David Lloyd Club. It adds, “As these investments are taking longer than expected to generate material returns, adjusting for the same (including goodwill), the overall gearing ratio (measure of financial leverage) as on March 31, 2019 stands at 1.57x, up from 1.11x as on March 31, 2018.” The ideal gearing ratio for a company like Talwalkar should be under 1%, according to analysts.

Dubious demerger

As if borrowing like a boomer and spending like a millennial were not bad enough, the company seems to have managed its demerger like a sloppy teenager. You could see the funny side of what happened at the demerger in 2018, if you were not among those who invested. Confusion reigned on the bourse that day.

The more lucrative gym business (71% of revenue) was moved out as Talwalkars Lifestyles (now known as TH. The one with the higher-end services was retained with the existing company, as TBVF. The plan was to switch names at a later date, once the gym business was listed.

It was enough to tie a knot in your brain. And it did. People assumed that the one with “fitness” in its name was the gym business. They bet big on it, and lost a packet. “The demerger was a big fiasco. Investors got confused with this name swapping. On listing day, the stock which should have been valued at 25% (of total market cap, as per its revenue contribution) was quoted at 75%. So those who purchased TBVF shares on that day consistently sold off and the stock kept hitting the downward circuit,” says an analyst with a leading brokerage firm.

Another evidence of the haphazard manner in which the demerger was executed is pointed out by Samarth Singh, analyst, TPF Capital. Unlike most investors, Singh was more interested in the club business listed under TBVF, as the entity also owned eight properties across Bandra, Mulund, Raipur, Sholapur, Jodhpur, Jamshedpur, Kolkata and Rajkot, valued at Rs.1.3 billion by ICRA in February 2019. These properties were to be rented out to TH. The gym business spent Rs.375 million in rent for FY18 (all rental properties, and not just for the ones from TBVF).

“Though TBVF wasn’t a major part of the business, we were interested in the real estate. It gives a more steady cash flow and can be valued easily,” Singh says. However, during the analyst call on February 9, 2018, when he asked them if the agreements are in place — whether it will be a leave licence agreement or lease agreement, they said that they will figure it out post-listing. “Real estate rentals were a major source of revenue for TBVF, so it was surprising they did not give estimates for this income,” he says. Even in the May 8, 2018 call, a month before the demerger, Singh asked them a similar question. But the management was evasive. They said that the rental would have to be decided after discussing with the bankers. That it would be “inappropriate” to cite a figure that could then go wrong.

The fund manager, meanwhile, questions the very reason for the demerger. “At the time of announcing the demerger in December 2016, TBVF had a total market cap of Rs.7 billion-7.5 billion. Why did they demerge such a small-cap company?” He says only demerged entities of large companies would be attractive to investors. “If you are a very small company undergoing a demerger, it will result in liquidity crunch,” he adds.

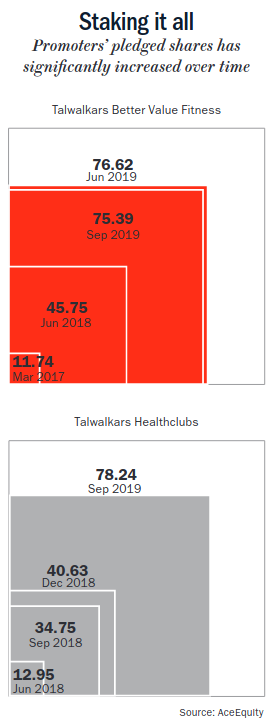

Perhaps sensing the tough times to come, a number of board members have exited the company in the past year and half (See: Staking it all). At the senior management level, Prashant Talwalkar, managing director and CEO has resigned. Wholetime directors Anant Gawande and Harsha Bhatkal, and independent directors Avinash Phadke, Dinesh Afzulpurkar, Raman Maroo, Mrunalini Deshmukh and MG Bhide have opted out. But Gawande continues to run the show as the CFO of the company. Meanwhile, auditors have scooted too; Lakdawala and Associates in February 2018 and MK Dandeker & Co in August 2019. Neither TH nor TBVF have an external auditor now. Even mutual funds and foreign investors followed suit. Interestingly, KP Lakdawala, proprietor of Lakdawala and Associates is also a partner at Lakdawala & Co, the firm that was the auditor of PMC Bank in FY18 and FY19. This co-operative bank is being investigated for a Rs.65 billion scam which involved hiding irregularities in its loan accounts related to HDIL.

Evolving ecosystem

While the company is floundering, the ecosystem is fast changing. True, unorganised players still have 97% of the market share. But, the opportunity is expected to nearly triple in five years. India’s fitness market is currently $2.4 billion and is expected to reach $6.2 billion by 2024, according to a study done by fitness aggregator Fitternity.

The business has a low entry barrier and minimal scope for differentiation. Even Talwalkars with its history cannot charge much higher than other fitness chains, such as Gold’s Gym and cult.fit, which came in later. Each of them has priced their annual membership at Rs.25,000-Rs.30,000. Meanwhile, newer entrants are offering more flexible and varied options at around the same price.

Take Fitternity for example. It started out as an aggregator and discovery model in 2013. “We look at users in two buckets. Old world are users who take the annual membership of a gym which they might not use for various reasons. But the new age users want bang for their buck,” states Neha Motwani, co-founder, Fitternity. To cater to this new-age user, the company has come up with options such as ‘pay-per-session’ and ‘one pass’. As the name suggests, pay per session allows a user to book a gym session nearby, while ‘one pass’ allows holders to access any gym listed on Fitternity throughout the year, irrespective of the chain or the city. This pass costs Rs.4,000 for a month and Rs.25,000 for a year, and will give users access to 12,000 gyms.

Motwani says that 45% of their users opt for pay-per-session and one pass. “It is too soon to tell,” she says, “but it seems people may enter fitness looking for familiar routines, but as they mature as users, they may choose to pay per usage or one pass.” Fitness enthusiasts may not want to be tied down to one gym, however fancy their equipment. The fund manager quoted earlier says that residential and commercial buildings and complexes today come with gym facilities. Why then will a person take a gym membership? Fitness is a growing trend, but unless a gym has a strong differentiator, its membership numbers are likely to drop.

Slowdown blues

Companies across industries are struggling with the slowdown and the liquidity crunch. But these could be death blows for a small company heavily reliant on debt.

An analyst states that things came to a head in 2019. “Last year, small caps crashed, which meant the company couldn’t raise more equity capital. At the same time, credit markets tightened, which meant they couldn’t refinance loans easily and raise incremental debt. If you are a company with negative cash flow, then without additional capital and debt, you will default. Which is what has happened,” he says. Over the past year, the company has defaulted on loan and interest repayments to its lenders. Most recently, it failed to repay Rs.26.4 million to Tata Capital, whose total exposure to Talwalkars stands at Rs.368.5 million. Not wasting any time, the lender approached the Bombay High Court. Through all this, the company has maintained its silence.

Evidently, Talwalkars faces liquidation risk if its debt coverage ratio does not improve. In order to salvage the ship, the management has swung into action. Credit rating agency Care states that the management is looking to raise funds through various avenues such as sale of equity, sale of stake in joint ventures/associate companies and monetise some of its gym properties by entering into a sale and lease back transaction to partially retire its debt.

Analysts, however, aren’t biting. With 75% of the promoters shares pledged, analysts feel hoping the tide to turn in Talwalkars’ favour is a bit farfetched. Gupta points out that this means the promoters have just “empty voting rights”, without any financial stake. He says the current mess cannot be attributed solely to the promoters, adding that auditors and independent directors are also to blame. “Independent directors claim that they are on non-executive roles. They are treating their role as an afternoon golf game. Nobody wants responsibility. Ultimate losers are investors,” he adds.

All eyes are now on the company’s pending annual general meeting and Q2FY20 results that were to be declared in September. No new date has been fixed for either. Analysts expect the best case scenario to be one where the company sheds assets and generates enough liquidity to start growing again. As for the worst case, nobody is sticking out their necks.