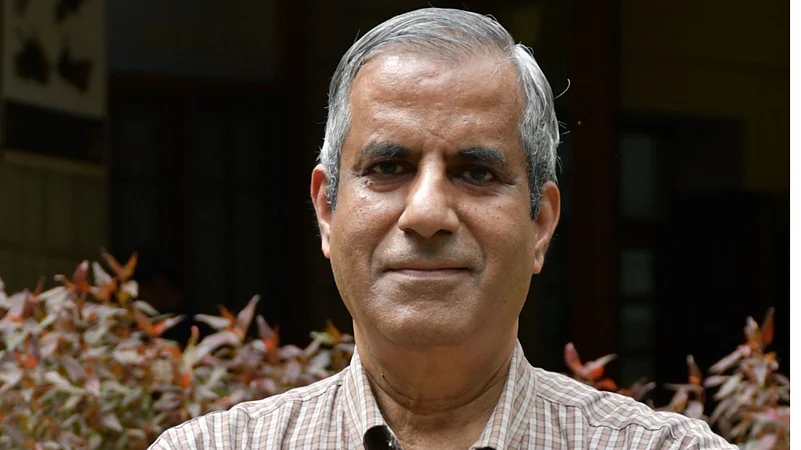

The government often assumes successful initiatives will sustain themselves after the first round, says FSID’s Balan Gurumoorthy

Fear of failure and low confidence continue to hold back research investments

Indian consumers still choose the best product available rather than consciously backing local ones

One of the oft-repeated complaints about India's start-up ecosystem is its tilt towards services. The country has produced globally competitive IT firms and a thriving gig economy, but far fewer original products—the kind built on proprietary technology and sold under Indian brands.

Professor Balan Gurumoorthy, Director of the Foundation for Science, Innovation and Development (FSID) at IISc Bangalore, sees this as a stage of development rather than a permanent condition. "Most countries follow a similar path—starting with imports, then local assembly, component manufacturing, full product building, and finally original design. India is already moving along this curve," he says.

At the same time, the early signs of change are hard to miss. Gurumoorthy points out that start-ups are emerging in spaces like gallium nitride semiconductors, where India, though five to ten years behind, can still catch up; and that parents now ask their children why they are not working at a start-up.

Yet problems persist, including at the policy level. Promising initiatives, for example, are abandoned too soon. Gurumoorthy points to SamridDHI, the Ministry of Heavy Industries' product accelerator program where he serves as a director. Its first cohort, funded at ₹67 crore, placed four products in the market. No second cycle is planned.

"There is an assumption within the government that once an initiative works in its first iteration, it will automatically become self-sustaining," he says. "That is a mistake. Expecting sustainability after just one round is unrealistic."

In this interaction with Outlook Business, Gurumoorthy discusses the path for India to become a product nation, why growth-stage funding is often more challenging than early stage, and the historical reasons behind our continued underinvestment in research and development.

Edited Excerpts

When discussions turn to India’s innovation ecosystem, a recurring concern is that the country is still not seen as a strong product nation. Why do you think that is?

There are several reasons behind this. When technology was taking off globally, India was not yet independent, which shaped a culture of consuming rather than building products. While this may sound like an excuse today, it had lasting effects, making it difficult to close the gap as global products continued to improve rapidly.

Even now, consumers in India prioritise the best available product over consciously supporting local ones. While this is a healthy market instinct, it slows the development of a strong product ecosystem, which needs early, engaged users to provide feedback and drive improvement.

India is also a relatively young nation, just over 75 years old, and building a product culture takes time. With sustained investments in education and infrastructure, the country may now be approaching a stage where those long-term efforts can start paying off.

At the same time, when we talk about investment, India’s spending on research and development has not been significant, both within the government and across the corporate sector?

Most countries follow a similar path, starting with imports, then local assembly, component manufacturing, full product building, and finally original design. India is already moving along this curve.

The hesitation around research often comes from low confidence and fear of failure. Working with proven products feels safer, much like film producers preferring remakes over original stories. Research has also seen limited investment due to doubts about commercial returns and a lack of visible success stories.

There have been early attempts at indigenous products, such as the Sumeet Mixer in the 1960s, which briefly succeeded by addressing local needs. While many such efforts did not scale long term, they show that the foundation existed, and the ecosystem now needs to build on these experiences more consistently.

Have things changed for start-ups in recent years?

They have changed over the last few years. While it is hard to generalise at an individual level, the government as a whole has created a strong buzz around start-ups, which is a positive development. At the very least, young people no longer face the same parental pressure as before.

In fact, some parents now ask their children why they are not working at a start-up. Earlier, the comparison at home was always about someone else earning more, which added to the pressure. That shift in mindset is a good thing.

India is often seen as having missed the semiconductor wave, yet start-ups like Agnit [semiconductor start-up] suggest growing deep-tech capability. What does this say about India’s semiconductor ecosystem, and what still needs to improve?

In the traditional silicon-based semiconductor space, India is late. However, with the push the government is now giving, manufacturing could begin to catch up.

In gallium nitride (GaN), the opportunity is stronger. We are behind, but not irreversibly so. From discussions with colleagues, India is roughly five to ten years behind, but this is a gap that can still be bridged because the technology has not yet run too far ahead.

At the institute, facilities have already been set up to support start-ups, and RF devices are now being developed and prepared for commercial sale. Power electronics is the next area expected to follow.

As more users come onto this shared infrastructure, talent and scale will begin to build, creating the critical mass needed for India to become a meaningful player. Credit is due to the team that worked to get the fabrication facility operational.

The next step is to attract more start-ups. At present, there are about three, and interest is growing from both start-ups and corporates. While the mandate is to create start-ups in this space, the facility will also provide services to larger companies.

From a longer-term perspective, while India is clearly behind on the hardware side, particularly in fabrication and device realisation, the situation is very different in fabless chip design. The talent already exists in the country. If India chooses to focus strategically on fabless design and builds companies rather than just supplying individual talent, this is an area where it can compete globally.

Given your experience with both academia and industry, how is the Pravriddhi initiative [product accelerator program] bridging the gap between the two, and what are you doing differently?

The key difference is [that it is] a deeply collaborative approach with industry. Rather than offering finished solutions, they are co-developed with companies, with most design and execution happening at the industry site. The institute supports this through labs, simulations, testing and expert guidance, while the ownership of the build remains with industry.

The goal is to give companies confidence to build products from scratch, with close, hands-on involvement rather than light mentorship. However, challenges remain, especially in testing and certification, which are costly and often handled by international agencies, as well as gaps in industrial-grade testing infrastructure.

Another major constraint is the shortage of talent in product engineering and product management. While India excels in IT services and project management, product-led innovation requires different skills. The opportunity now lies in helping India’s strong mid-level talent transition into product-focused roles.

How can academia play a role in it?

Academia has a clear role to play in teaching and training, and that is fundamentally its responsibility. That said, product management is not something that can be fully taught in a classroom. Parts of it can be taught, and we do teach those aspects.

At IISc, for instance, we run a program in product design, which has now been rebranded to reflect a broader focus on product management and development. This change acknowledges the reality that we no longer need only designers, but also professionals who can manage the entire design process, as well as engineers who can execute it end to end.

Even in design education, the number of courses has historically been limited, although that is beginning to change. Today, there are far more design programs across the country than there were a decade ago, particularly in private institutions. This is a positive shift.

However, many of these capabilities need to scale simultaneously. Since they do not always grow at the same pace, reaching equilibrium will take time. Still, the direction is clearly the right one.

FSID is also working closely with start-ups on developing new material families for battery technologies to reduce dependence on lithium. Given the current geopolitical environment, this work has become especially relevant. One approach is to explore alternatives such as sodium-based batteries and other promising material families. Here again, the pathway involves foundational research followed by translation through start-ups and companies.

At the same time, with support from the Department of Mines under the Ministry of Mines, a focused initiative has begun to study rare-earth elements, critical materials, and magnet materials. Energy is one part of this effort, mobility is another, and both are being addressed from a foundational research perspective.

There are two key challenges in this area. The first is identifying new material families worth pursuing. Second, even when India possesses raw material resources, they often exist in very small concentrations. Like the challenges historically faced in coal extraction, conventional techniques used elsewhere may not be effective here. As a result, India will need to develop its own methods to process and extract these materials efficiently.

In terms of the government sector, are there any specific areas you think we should focus on that would also help academia also advance its research?

I think there are two key things to focus on. The first is sustaining such efforts. To explain what I mean, take the product accelerator program [SamridDHI]. We ran one cycle, and by any reasonable measure, it was a success. Four products have already reached the market, which shows that the idea works and is worth continuing.

However, the government is not planning another cycle of the program. The ministry involved has other priorities and is exploring different mechanisms. There seems to be an assumption that once an initiative has worked once, it will automatically become self-sustaining. That is a mistake. Expecting sustainability after just one round is unrealistic.

This pattern is common across funding efforts. Programs are often expected to stand on their own very quickly. The example frequently cited is Germany’s Fraunhofer institutes, which generate significant industry funding. What is often overlooked is that they continue to receive block grants from the government. That baseline support, with the government acting as an anchor customer, provides confidence and stability.

This is a fundamental point. When core costs are covered, people have the confidence to pursue ambitious, high-risk work. Without that assurance, the tendency is to choose the safest option. Sustained support, even if it tapers over time, is essential for building long-term capability.

How much was the funding for the first cohort?

The first cohort was actually very well funded. The total funding was around ₹67 crore, of which about 25 percent came from participating companies, while the government contributed the remaining 75 percent. I am not suggesting that every stage needs the same level of funding, but some form of structured, phased support is essential.

This lack of sustained support is something deep-tech start-ups often point to as a reason for shutting down.

It is not just about funding, but also about the absence of early orders. A common counterargument is that failures happen all the time in the US, which is true. But that ecosystem is far more mature. Founders there can pivot quickly, raise money again, and restart without stigma. That confidence does not yet exist here, and it needs to be built.

Trying to replicate the Silicon Valley model overnight is not realistic. It has to happen gradually. There is a time when ventures need to be nurtured and a time when they should be allowed to operate independently. My main suggestion to the government would be to sustain funding and not assume that once something is seeded, the job is done. Support may reduce over time, but it cannot disappear altogether.

From the private sector’s side, companies also need to step up. During downturns, there is often a lot of complaining, but little willingness to share the burden. Innovation cannot work on the assumption that everything—from orders to design to manufacturing—will simply arrive ready-made. Companies need to take initiative, find partners, roll up their sleeves, and be willing to absorb some of the risk as well.

Growth-stage funding remains a challenge in India. Is that holding us back?

A persistent challenge remains at the growth stage. When we look at companies like Agnikul, there is significant venture capital interest and several private partnerships. However, sustaining a company at the growth stage is still difficult.

Growth-stage funding in India has consistently been low, reflecting a traditionally limited appetite for large, long-term bets in deep tech. That is something that needs to change, and hopefully, it will over time. Early-stage funding, while smaller in size, carries higher risk. Growth-stage funding, on the other hand, involves much larger capital commitments, even though the risks are better understood. For companies like Agnikul, particularly in sectors such as semiconductors, funding requirements run into tens of millions of dollars, not just a few million.

The ecosystem is slowly evolving. Just as investors today are comfortable backing early-stage tech companies with relatively modest cheques, the hope is that, in time, there will be greater confidence in writing much larger cheques for growth-stage companies in the same space. Once a few success stories emerge, that confidence is likely to grow further.

When speaking to deep-tech founders, they often say investors are reluctant to fund them, while investors argue that founders have strong technical knowledge but struggle with execution and market readiness. Do you also see this gap?

The gap I see is that capital providers often lack the appetite to invest in what we define as deep-tech companies. At the same time, many deep-tech founders tend to be overly focused on their technology and less attentive to what it takes to succeed in the market. To some extent, both views are valid.

The question then is how to reach a middle ground. On the founder’s side, one effective approach is to provide strong operational support. This can take the form of business mentors, not in a light-touch or advisory model where someone is available for a few hours a week, but as a dedicated, one-on-one partner working closely with the company. As an incubator, we often underwrite this cost for three to six months until a strong working relationship develops between the mentor and the founder.

On the investor side, we are increasingly realising the need to bring in early-stage capital ourselves. This allows founders to demonstrate initial market traction. Once a founder approaches investors with paying customers or clear demand, the conversation changes entirely, and investors are far more likely to take the opportunity seriously.

Some deep-tech start-ups launch revenue-generating products to attract investors, while continuing their core R&D in parallel. They say that this helps secure capital without losing focus on long-term innovation. What do you think about this strategy?

It is a tricky call. I may not be the best person to make that judgment, but that is the caution I would offer. I have seen founders attempt quick fixes, not in a superficial way, but along similar lines. Some start by offering services around their product while continuing to refine it, which I believe is a sensible model.

At the same time, parts of the investor community are also evolving. More investors are beginning to see the long-term value of staying invested in companies that follow this approach. Hopefully, this will lead to better outcomes going forward.

When we look at new-age companies in India, the number of patents filed remains low. Why do you think this is?

The higher the number of patents, the stronger the signal that quality research is taking place. As a nation, this is one of the challenges we need to address. Whether it is government, academia, or industry, investment levels remain low, and this is something that must be fixed.

I come from an academic system that I believe is a good one, especially given the context we operate in. Institutions such as the IITs, IISc, and IISERs are far better off today and are performing well. However, at a national level, they still represent only a small fraction of the overall ecosystem. That gap continues to exist. There is a clear connection between the number of patents, the quality of research, and broader outcomes such as higher education participation.

The data shows a strong correlation between GDP growth and higher education, particularly beyond school. At our institute, this is reflected in a sharp rise in patent activity, with around three patents filed every two days.

This momentum traces back to the founder’s vision of prioritising original investigation and research. Today, the institute has about 5,400 students, including nearly 2,800 PhD scholars, an unusually high share, even globally. But nationally, the number of patents filed is still low. This reflects [the need for] a serious, long-term commitment to knowledge creation, supported by sustained investment in infrastructure.