Not long ago a logistics start-up valued at a staggering $878mn was planning to go for a blockbuster initial public offering (IPO). Then things changed.

As the funding winter set in, the company unravelled. However, that isn’t something new. Start-ups falter all the time.

“But what stood out was the nonchalance of the investors. Nobody cared. There was no effort to take stock of the situation,” says a senior executive who is on his way out after a fire sale of the company to a bigger rival.

“The thing is that the biggest shareholders were sitting thousands of miles away. And one portfolio company in India going bust didn’t really matter,” he rues.

Many in the start-up ecosystem echo his sentiment. The going was good for the better part of a decade as foreign venture investors like SoftBank, Tiger Global and Sequoia Capital pumped in billions of dollars. Start-up founders were made to feel like celebrities, valuations skyrocketed overnight and unicorns blossomed.

Capital Crunch

However, once the music of the zero-interest-rate policy era stopped, these funds have quietly stepped back. While Sequoia shut shop in India after a string of governance lapses at its portfolio start-ups, Tiger Global and SoftBank retreated as a response to changing macros. The same goes for Alpha Wave which has turned its focus to mature late-stage businesses rather than start-ups in India.

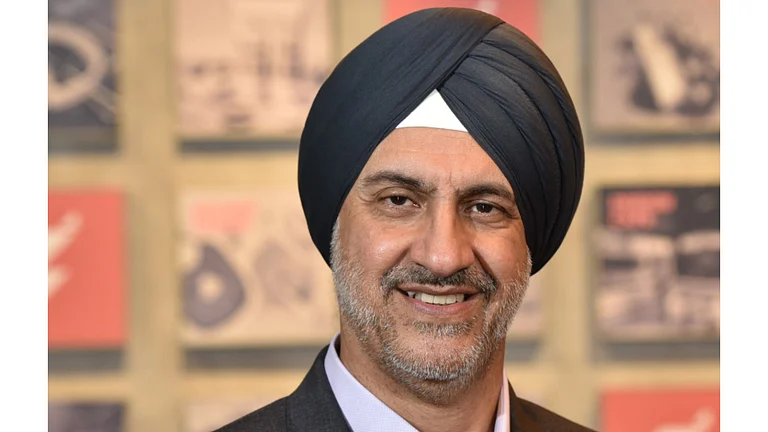

“When you have a foreign PE [private equity] or VC [venture capital], they’re obviously subject to a fairly high degree of volatility over time. There could be sovereign risk, currency risk, political risk and geopolitical risk. That’s why it behaves every country to develop a local pool of private capital that won’t fly away in the face of volatility,” says Sanjay Nayar, president of industry body Assocham and a veteran private-equity investor.

The fact that India has not produced companies that dominate international markets isn’t due to a lack of entrepreneurial talent or ambition. It’s because, beyond the early stages, there is a glaring absence of deep, domestic capital to help them achieve global scale.

By contrast, China has produced global tech giants. Beijing’s state-backed funds, local venture pools and a maturing base of homegrown investors have ensured that capital remains available to promising Chinese companies.

“China has been incubating a local PE/VC ecosystem for the past three decades,” says Nayar.

He believes it’s high time India takes the cue from China and builds a large funding ecosystem. And the veteran financier is putting his money where his mouth is. After a career in private equity that included setting up and scaling investment firm KKR’s operations in India to $14bn, he has started his own VC firm called Sorin.

And he isn’t alone.

According to data from Venture Intelligence, the number of domestic PE/VC funds has jumped 10-fold over the past decade—from 14 in 2014 to 145 in 2024. For the first time in 2019, the industry raised funds of over $2bn in a year—and that has remained true for every year except 2020 when Covid struck.

Fuelling Aspirations

After completing his master’s in electrical engineering from Stanford, Pranav Pai stayed back in Silicon Valley and worked at a start-up. When the start-up was acquired, Pai cashed in big on his employee stock options. It was 2015 and he decided it was time to head back home to Bengaluru.

“When I met a lot of founders, my first surprise was that they all hated raising venture capital. They were feeling very suppressed in India. They felt like the VCs were very robotic on thesis and founder selection. There were only seven or eight business models that the VCs were interested in—like e-commerce, food delivery, ride-hailing or payments. If a founder was doing anything outside that set, they didn’t even get a meeting,” he recollects.

So, Pai along with his brother Siddarth started 3One4 Capital with the aim of funding new categories of businesses. These didn’t have to be proven formulae mimicked from Silicon Valley or China. And he wanted to index more on deep tech, a category that accounts for 21 of the 110 investments made by the firm to date.

A few years before Pai started 3One4 Capital, a former Airtel honcho named Sunil Goyal had made a hefty sum on his stock options after the telecom company went public. He started a VC firm called YourNest to invest in deep-tech start-ups. His thesis was that sooner rather than later the country would shift from being an information technology (IT)-outsourcing hub to an intellectual property-driven product nation.

Of course, it is not that all domestic VCs are just making deep-tech bets.

Fireside Ventures and Sauce are funding local consumer brands that can disrupt multinationals like Nestle or Unilever. Then there are those like climate-tech fund Synapses or gaming fund Lumikai.

“It is absolutely essential for a country the size of India that its economic aspirations should be tied to its own funding infrastructure. Just as you need domestic banks, insurance companies, you need your own LPs [limited partners] and GPs [general partners],” says Gopal Jain, founder of private-equity firm Gaja Capital.

Family Matters

Kushal Khandwala, the scion of a realtor-to-financing group based in Gujarat, became fascinated with Shark Tank, a business reality show, when he was studying for his master’s in the UK. He was not content to see his wealth compound by 15–20 percentage points a year.

So, when he returned home, he sought out VC funds to invest in through the family office. Two of the funds where he put his family’s money were Sixth Sense Ventures and Fireside Ventures.

Khandwala wasn’t alone. The earliest believers in India’s domestic VCs were high-net-worth individuals (HNIs) and family offices.

This early capital was often relationship driven and flexible, helping new GPs like Fireside which was backed by the Mariwala family, or India Quotient which started in Paytm’s office. In industry parlance, managers of PE/VC funds are called general partners (GPs), while limited partners (LPs) provide them with capital with limited liability and no management role.

“Initially the largest contribution came from consumer companies or their promoters’ family offices. The Mariwala family, Premji Invest, Sanjiv Goenka family, Sunil Munjal family—they all invested in us because they understood the phenomenon,” says Kanwaljit Singh, co-founder of Fireside, a VC investor in new age consumer brands like Mamaearth and boAt.

Global LPs were not particularly interested in Indian VCs till the Flipkart moment happened. Till then, the sovereign-wealth funds and pension funds were content on getting a slice of the Indian private capital market mostly via the global GPs.

For the domestic GPs, it has been an uphill battle to attract global capital. First, the US stock market has grown at a compound annual growth rate of over 10% and the Nasdaq has logged around 15% over the past two decades. This has meant that LPs have sought to cash in on the more stable returns in a more mature market rather than deploy too much in risky emerging markets.

Moreover, the continual slide of the rupee against the dollar has not helped as this means that exits from the Indian market don’t necessarily translate into bigger returns in dollar terms.

Another factor was that—for the longest time—the global LPs saw India primarily as a hub of arbitrage businesses, such as the IT sector, which don’t generate substantial profits akin to product companies like search engines and social-networking platforms.

However, as the top bracket of Indian VCs generated competitive returns in their initial funds, global LPs have started taking interest over the past five years or so.

According to data from rating agency Crisil, over the past four years, Indian early-stage venture funds delivered an internal rate of return (IRR) of 26.9% as of March 2024, beating the BSE 250 Smallcap by 4.3 percentage points. Growth and late-stage funds posted an IRR of 23.6%, outperforming the BSE 200 by nearly 6 percentage points.

“As a result of the returns that we have demonstrated, there is a lot more interest in India now from global LPs. We’ve raised from American university endowments, European investors, Japanese investors and Singaporean LPs. The same kind of investors that global firms raise from—we have access to maybe 50-60% of those today,” says Pai of 3One4 Capital.

“We don’t have the same level of access to other nationalities’ family offices, pension managers, or sovereign LPs and state pension programmes,” he adds.

A Glaring Gap

When Sunil Goyal joined Airtel as an executive assistant to the chairman at the turn of the millennium, the telecom company was one of the hottest start-ups in India. As it raced towards an IPO, it needed to raise a massive round of growth capital.

“This was in May 2001. We were at the Belvedere [a club] in The Oberoi [in Delhi] for a board meeting when Sunil Mittal [Airtel founder] said that he wanted to lock down the funding round that day itself. He offered a 15% discount and Warburg Pincus didn’t miss a beat to say that it will invest the full $300mn,” recalls Goyal.

As the bet grew six times over in no time, it was a dream deal for Warburg Pincus. The New York-headquartered investor exited its holding for $1.8bn in 2005, making a profit of a little over $1.5bn within a short span of time.

While many celebrated the exit, it disturbed Goyal that no Indian investor could make a single penny from what was one of the biggest Indian start-up successes of the time. This was one of the reasons he started YourNest to back Indian start-ups.

As foreign PE/VC firms bet big on Indian internet start-ups over the past decade, they scored the biggest exits and took back home the spoils of victory—be it the $16bn acquisition of Flipkart or the $20bn public market debut of Paytm.

While the domestic VC boom has filled the early-stage capital void and brought local context to pre-Series A funding, the gap remains painfully wide at the growth and late stages, just when companies are preparing for the public markets.

It’s not that growth and late-stage domestic GPs don’t exist. Firms like Gaja Capital, Multiples Alternate Asset Management, Chrys Capital and Kedaara Capital have been quietly laying the groundwork for the past couple of decades. But the problem is that the sector has not exploded like VCs as growth-stage funds need access to billions of dollars of LP capital, which is not yet available in India.

Without Indian growth-stage capital, the risk remains that India may continue creating its best companies for someone else’s benefit.

Take for example Flipkart. In 2018, US retail giant Walmart acquired a 77% stake in Flipkart for $16bn, then the world’s largest e-commerce deal. Founded in 2007 by Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal as an online bookstore, Flipkart had come to define India’s start-up boom. But post-acquisition, both founders were gradually edged out.

Today, Flipkart is valued at around $35–40bn, making it India’s most valuable homegrown e-commerce company. Yet the spoils of this value creation largely accrue to Walmart that now controls over 85% of Flipkart.

As India’s start-up ecosystem matures and begins listing on domestic bourses, global private equity and venture-capital firms such as SoftBank, Tiger Global and Prosus are reaping massive windfalls.

These firms entered early or mid-stage, took large bets and now routinely exit with outsized returns during IPOs. Case in point: SoftBank and Tiger are set to be among the biggest beneficiaries in IPO-bound companies such as Lenskart and Meesho.

Ironically, while the technology is built in India, the consumers are Indian and the IPOs are held on Indian stock exchanges, the ultimate wealth extraction often flows overseas. Indian retail investors provide the liquidity and confidence needed for these listings to succeed.

“Every year, $35bn flows into VC/PE investments in India, but only 20% or so is local. The result? Nearly ₹2 lakh crore in profits leaves our shores. India cannot afford to keep exporting capital while our own pension pools sit idle,” says Gopal Srinivasan, chairman of TVS Capital, chairman of TVS Capital, a Chennai-headquartered growth equity fund.

The domestic ecosystem still doesn’t have the financial wherewithal to satisfy the funding needs of IP-led start-ups for the long haul

But it is not just this route through which India loses out on value creation by its innovators. A lot of Indian founders choose to sell the company or move to the US or Singapore to access bigger sources of funding and scale up.

AI start-up Halli Labs was acquired by Google; Mango Technologies, which built OS stacks for feature phones, was absorbed by chipmaking giant Qualcomm; and Perpule, which developed cashier-less retail technology, became part of Amazon. These Indian companies created globally relevant IP but were scaled or monetised abroad, highlighting how innovation born in India often migrates to foreign shores.

One of the earliest bets that 3One4 Capital made was a biotech start-up called Bugworks that had found a new way to fight antibiotic resistance. Yet, the company was compelled to flip its domicile to the US to be able to access bigger amounts of funding needed to develop the product.

Anand Anandkumar, the founder and chief executive of Bugworks says he would have had to shut down his company if it had not moved to the US five years ago.

“They either go bust or become a services company or figure out a way to get funding from abroad,” he says.

Regulatory Shackles

The US and China are the two countries that have used the depth of their domestic capital pools to fund their tech and start-up ecosystem.

The US did it through free-market policies by easing taxation and capital allocation rules that allowed its financial institutions like banks, insurance firms and pension funds to invest in PE/VC funds as they saw fit. Meanwhile, China’s modus operandi has been to create state-backed funds.

“In contrast, India’s policy has been half-hearted. It can’t make up its mind which approach to take. On one hand, it would be right to say that Sidbi [Small Industries Development Bank of India] fund of funds corpus of ₹10,000 crore has been instrumental in creating the domestic VC ecosystem,” says the partner of a Mumbai-based investment bank.

But he goes on to add that there is so much regulatory cholesterol that PEs and VCs have to be on their toes all the time.

Take, for instance, a 2023 directive from the RBI which intended to curb conflicts of interest and ensure credit prudence. The regulation prohibited banks from investing in alternative investment funds (AIFs) that in turn invest in companies to which the bank has any credit exposure. To make matters worse, banks and non-banking financial companies together now can’t contribute more than 15% of an AIF’s total corpus. Insurance companies face similar restrictions.

The biggest sore point for the PE/VC ecosystem however is their inability to raise capital from the Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation which has a corpus of over ₹25trn (or $291bn). Although the Centre changed its stance in 2021 to permit 5% of its corpus to be invested in PE/VCs, there has been no allocation yet.

Charitable trusts too have rules specifying where they can invest. “IIT Delhi’s endowment fund can invest in mutual funds. It can back start-ups directly. But it cannot invest in a professionally managed VC fund. The regulations make no sense,” says a VC fund manager.

The opportunity cost of this regulatory stasis is enormous. India has over 1,500 registered PE/VCs and hundreds of new start-ups forming each year. But the lack of local institutional LP capital means most funds either stay small, or rely on foreign capital, which itself is drying up in the current macro environment.

“These are idiosyncratic barriers that no longer have any relevance. Our banking system has $2.5trn of deposits, mutual funds have $700bn of AUM. By contrast, the total domestic capital into AI so far is about $60bn. All we need to do is to remove the roadblocks and allow domestic capital to flow into funds,” says Jain of Gaja Capital

Here Comes the Taxman

It’s not that the government and regulatory agencies are blind to the issues faced by the PE/VC ecosystem. But the problem is that the bureaucracy is too slow to respond, say industry insiders. And, more importantly, the sector has found that easing of rules often comes with a catch.

Take for instance the angel tax law. It was introduced in 2012 as a measure to stop the menace of money laundering masquerading as high valuations.

As investors and start-ups cried themselves hoarse over the next decade over unfair demands made by taxmen, the government sought to find a solution by tweaking the rules. But it simply didn’t work out. An overeager tax official would always find a way to make a demand to meet collection targets. Ultimately, the angel tax was abolished last year after 12 years of harassment.

Similarly, another long-standing gripe of the private market had been its higher tax treatment compared to the listed market.

“At one point, unlisted investments attracted 2.36 times the tax compared to listed, once you accounted for all surcharges. So, it hurt the appetite for investing in PE/VC funds and effectively this made it harder for us to compete against the stock market for money from family offices and HNIs,” says Pai of 3One4 Capital.

“Now, thankfully, after a substantial amount of effort from the industry side, the government has rationalised the tax rate between listed and unlisted,” he adds.

National Interest

At an annual gathering of the country’s start-ups in Delhi earlier this year, Union minister Piyush Goyal ruffled many feathers as he remarked that India’s VCs were focussing on grocery and food delivery, while not backing enough start-ups in deep-tech segments like robotics and electric vehicles.

VCs point out two things: one, that there aren’t many investible deep-tech start-ups in the country to choose from. This is the case because there aren’t enough research grants in universities.

The second issue is that the domestic ecosystem still doesn’t have the financial wherewithal to satisfy the funding needs of IP-led start-ups for the long haul.

Although several deep-tech-focussed domestic VCs like Speciale Invest, Pi Ventures, YourNest and others have tried their best to move the needle in deep-tech funding—from 50 investments in 2014 to 230 in 2024—it hasn’t been easy.

It is no secret that foreign PE/VCs, especially in the US, have always sought to make Indian start-ups flip abroad. For example, YCombinator, one of the best-known start-up accelerators globally, sets US domicile as a precondition to fund a company.

Today, Pixxel, which is one of the most promising space-tech start-ups in India, is domiciled in the US. While the company hasn’t disclosed its reason for the shift, industry insiders say that a defence contract from the US government is likely to have prompted the move.

While some argue that in the past foreign investors asked start-ups to relocate just to avoid taxes in India, many believe that the geopolitical fragmentation of today makes it a tool to siphon away IP created in the country.

And the way to prevent this from happening is paving the way for India’s start-up ecosystem to access domestic pools of capital. At a time when countries are racing to develop and control emerging technologies like AI, India can’t afford to lose the plot.

If India’s start-up decade has taught us anything, it’s that capital is not neutral—it shapes the kind of companies that survive, the IP that stays and the wealth that circulates within our borders.

Now, with a generation of homegrown GPs proving they can deliver world-class returns, the question is whether India can unlock its domestic capital to build a funding infrastructure that spurs innovative companies like Nvidia and Apple. The challenge is to build them fast and large enough.

The clock is ticking for the nation’s economic sovereignty.