Despite a surge in small businesses and service providers, declared business incomes remain disproportionately low to salary income

Experts argue that classification issues and cash-heavy transactions have created a large grey zone

As digital payment growth moderates, policymakers face pressure to rethink how India taxes its services economy

India is losing substantial revenue due to persistent leakages in its tax system, particularly in its large and rapidly expanding services economy, and must urgently plug these gaps to raise its tax-to-GDP ratio—critical for funding social welfare and investments in human capital—according to former finance ministry officials.

Current officials argue that India’s tax-to-GDP ratio is not as low as critics claim, pointing to the country’s low per-capita income. Many tax experts and former officials dismiss this defence as a convenient excuse for the state’s limited success in curbing widespread tax avoidance and evasion, especially given India’s vast welfare needs.

According to the International Monetary Fund, India currently mobilises about 20% of its GDP through taxes and other revenues. While this is higher than some other emerging economies, including Indonesia and Malaysia, it remains significantly lower than countries of comparable economic size and population. China, for instance, collects roughly 26% of its GDP in revenues.

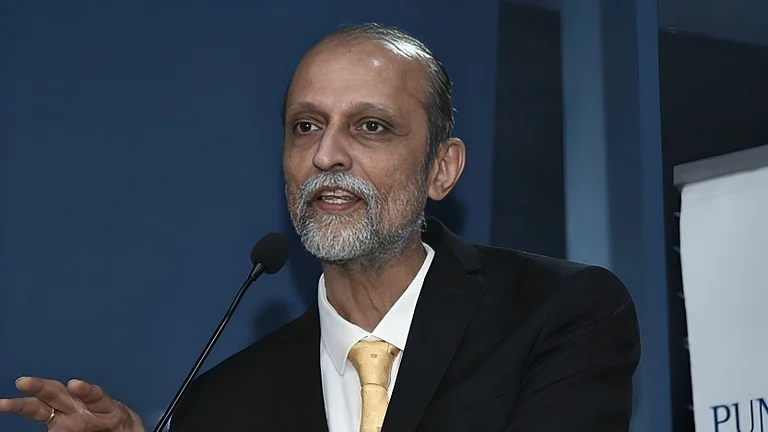

“Our system is extremely efficient at taxing salaries because they are transparent and easy to trace. But the moment you move into business or professional income, especially services, the opacity increases and compliance weakens,” says Akhilesh Ranjan, former member of the Central Board of Direct Taxes, while speaking with Outlook Business.

Hole in the Pocket

India’s income tax law offers simplified compliance to small and marginal businesses and professionals through presumptive taxation schemes, aimed at those who typically struggle with maintaining detailed accounts.

Under Section 44AD, traders and small businesses with an annual turnover of up to ₹2 crore can declare 8% of their gross receipts as taxable income and pay tax accordingly, without maintaining detailed books. To encourage digital payments, this presumptive rate is reduced to 6% for receipts made electronically, and the turnover limit is raised to ₹3 crore, provided cash receipts do not exceed 5% of total receipts.

Similarly, under Section 44ADA, professionals such as lawyers, architects, and accountants with gross receipts of up to ₹50 lakh can declare 50% of their receipts as taxable income. This threshold has been increased to ₹75 lakh for those whose cash receipts remain below 5%.

However, Ranjan points to a growing grey zone of service providers who fall outside these formal categories, such as operators of beauty parlours, tuition centres, and those offering various technical or freelance services. “They do not fit neatly into either category but make up a large part of our service-driven economy,” says Ranjan.

“Many of them earn far more than salaried professionals but end up paying significantly less tax by taking shelter under the 8% presumptive category. That is where we are losing substantial revenue,” he adds, suggesting a separate category for them.

In recent years, India has indeed seen a sharp rise in small and unincorporated businesses, led largely by service providers. According to the Annual Survey of Unincorporated Sector Enterprises 2023-24, the total number of such establishments increased from 6.50 crore in 2022-23 to 7.34 crore in 2023-24, a 12.8% rise year-on-year.

Within this, the “other services” category, which covers a broad range of service providers, recorded a 23.6% increase to 3.04 crore, far outpacing growth in manufacturing and trade. Many of these are India’s new middle earners who, unlike the traditional salaried middle class, operate in a grey zone between small traders and high-end professionals and arguably warrant a distinct classification. But the challenge does not end there.

Cash is King

Presumptive taxation has undoubtedly expanded the tax base, drawing millions of small businesses into the filing system. But it has not produced a commensurate rise in taxable income. A significant proportion of these returns continue to report incomes below the tax threshold, suggesting that compliance remains shallow.

The problem lies in self-reporting. With turnover under presumptive schemes largely declared by the taxpayer, income can be understated or transactions shifted into cash to reduce tax liability. In his study Do the Wealthy Underreport Their Income?, Ram Singh, Director of the Delhi School of Economics, finds that rental and professional incomes are particularly vulnerable to evasion because cash payments leave little verifiable trail.

The imbalance is visible in tax return data. In 2023–24, salary income reported by individual taxpayers was more than twice the business income declared, even as the number of small enterprises and service providers has surged across the country. And while reported business income is growing, it is doing so far more slowly than the expansion of India’s services-led economy.

At the same time, the momentum behind digital payments, long seen as a tool to formalise transactions, appears to be easing as well. “Digital payments have blossomed in India in the last few years and were expected to replace cash transactions,” writes Subhash Chandra Garg, former finance secretary, in a column. “In the last two years, however, digital retail payments growth has been noticeably moderating, whereas cash seems to be making a comeback.”

That moderation is striking because the scale of India’s digital payments expansion remains unprecedented. Digital retail transactions have increased more than five-fold since 2020–21, rising from about 44 billion transactions to nearly 222 billion in 2024–25, with their total value more than doubling over the same period. Much of this surge has been driven by UPI, which has become the backbone of retail payments, accounting for the overwhelming share of digital volumes.

Yet the pace of UPI’s rise has clearly slowed. After growing at triple-digit rates in the immediate post-pandemic years, UPI transaction growth has steadily decelerated, falling to about 42% in 2024–25, with value growth moderating in tandem. In recent months, transaction volumes have largely plateaued, averaging around 20 billion transactions a month, with only marginal month-on-month increases.

For policymakers, this matters because the early gains from digitisation, such as greater traceability and reduced reliance on cash, may now be tapering off. If digital payments growth slows while large segments of the services economy continue to operate in cash-heavy or self-reported regimes, the limits of digitisation as a tax-compliance tool become more apparent.

As experts argue, sustaining revenue gains will require far greater policy attention to India’s booming services economy. Policymakers will need to look beyond populist measures and address these gaps head-on to preserve both revenue and fairness in the tax system.