Delhi is the most polluted city in the world. Each winter, its air thickens until it feels like breathing inside a flour mill. The haze settles over everything. It crawls into homes. It clings to lungs.

And in this weather, if one has to sleep on the pavement outside India’s biggest government hospital for treatment, life itself can feel existential. Priyanka, a 30-year-old from Haryana battling a knot in her back, is living proof of what illness means when you are poor in India.

“There is no other option,” she says, shivering in the cold and polluted night outside All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in South Delhi. Around her, patients camp out on the cold concrete because they have nowhere else to go. They have travelled across the country with nothing but hope. Life narrows into a fight for breath, even as the city around them moves on.

It is a struggle Jyoti knows too well. “It took us four months just to confirm that my father had cancer,” she says. Her father, 67-year-old street vendor Sundar Lal from Raebareli, Uttar Pradesh, spent nearly a year shuttling between Delhi’s Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital and AIIMS. What began as a festering ankle wound ended with the removal of one of his lungs. By the time he was finally admitted in November, the family had lost its income, and Jyoti had lost a year of her education.

Doctors and economists say India’s premier government hospitals are overcrowded not because they are too successful, but because the system below them is too weak to hold. District- and state-run hospitals, starved of funds and stripped of expertise, cannot absorb the weight of demand. As a result, studies point out that India’s out-of-pocket health spending is among the highest in the world, a burden that extracts a punishing price.

Not far from the edge of this health-system collapse, another tragedy plays out. A short walk from the Murad Nagar metro station on the Delhi–Meerut corridor stands PM Shri Ukhlarsi Primary School No. 1. It tells a different version of the same national story, of a demographic dividend slowly and casually wasted.

This is a place meant to anchor children in learning but held together by the bare minimum. The classrooms do not have enough benches. The compound echoes with the absence of a much-needed support staff. The small building carries the exhausted look of an institution abandoned by the state, its needs piling up like dirt no one has been assigned to clean.

Teachers struggle to keep the school intact. Children clean the school themselves because there is no one else to do it. Most of the students come from the poorest families in the area. For them, this school is the first rung of opportunity, even as the structure meant to lift them falters in neglect. “We are managing with whatever little we get,” says Vartika Tripathi (name changed), a teacher at the school.

Across India, millions of children study in schools with facilities that belong to another century. As per the government’s own data, about 35% of state-run schools in India do not even have boundary walls, and therefore it is not surprising that only 46% have access to internet. In a nation that dreams aloud of becoming a superpower, many of its children sit in rooms that look as though they have been frozen in time.

This crisis in India’s health and primary-education sectors has a direct relation with the country’s economic growth.

“The productivity of India’s workforce has not risen significantly in recent years. If we want labour productivity to improve, we must invest in health care and education,” said Shamika Ravi, member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister (EAC-PM), in a recent interview with Outlook Business. She warned that primary health care can no longer be narrowly defined, as chronic and lifestyle diseases now hollow out the workforce long before old age.

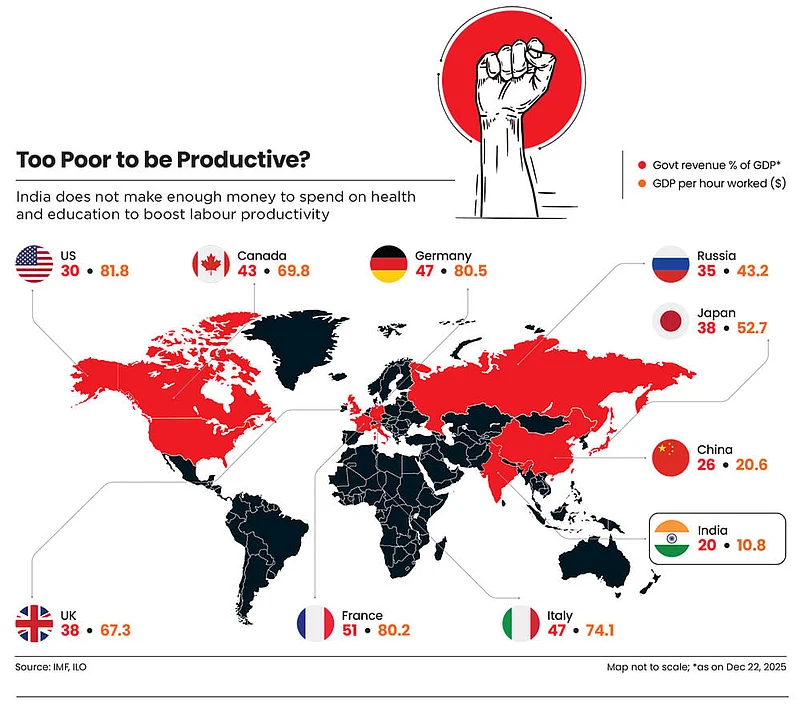

According to the International Labour Organisation, India’s labour productivity remains low by global standards. Its GDP per hour worked is estimated at around $10, placing it below countries such as the Philippines, Vietnam and Taiwan.

India at present fears a future in which it grows old before it becomes rich. A demographic dividend is never permanent. Indian policymakers have understood this in theory, but China always felt it in its bones. It acted with the instinct of a nation that knew history had offered only a narrow opening to escape centuries of deprivation. What followed was two decades of double-digit growth making it a power that the West fears today.

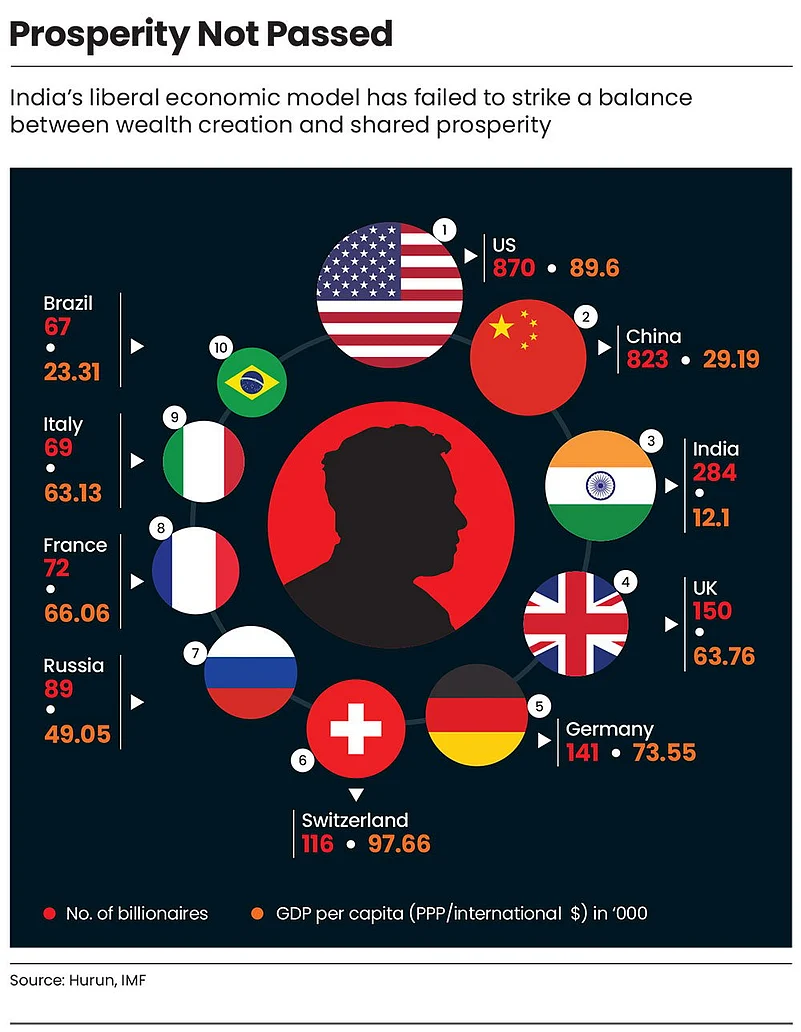

It is a case study in how two nations began alike but grew apart. In 1990, India and China stood shoulder to shoulder, young, restless and almost indistinguishable in promise. Three decades later, China has risen to become the world’s second-largest economy. India, now fifth, as per IMF’s October 2025 World Economic Outlook, is left to confront an uneasy truth. Its youthful workforce, once celebrated as its greatest strength, is edging towards becoming a burden, even as the gap in living standards between the two neighbours continues to widen.

Ask any wise policymaker in the country of 1.5bn, they say the solution is straightforward: spend more on health care and education.

Money spent on these sectors has increased in absolute terms, but their share of GDP remains well below the levels economists and government’s own documents prescribe.

The story of underfunded hospitals and classrooms is ultimately a story of limits, of a country tasked with lifting a low per-capita-income country out of the middle-income trap, but without the financial muscle to do so.

India’s goals have expanded far faster than its public finances.

On paper, education and health care are national priorities. In reality, they sit on the edges of budgets, competing with other critical investments and the rising cost of debt. The Centre speaks confidently about demographic dividend and global leadership, but its balance sheet tells a harsher truth that there is not enough money to do everything, everywhere, all at once. And when resources are scarce, it is spending on human capital that takes a back seat.

It took more than two decades after economic liberalisation for public health spending to even cross the symbolic threshold of 1% of the economy. Experts have long warned that this was nowhere near enough, consistently arguing that the country needed to more than double, even triple, its commitment.

The Centre argues that health and education fall largely within the states’ domain, while it must reserve resources for national priorities such as infrastructure, defence and strategic industries. For instance, the resurgence of tensions on India’s borders has reopened questions about defence preparedness and whether current allocations are sufficient.

States counter that they are asked to shoulder the most politically and socially sensitive responsibilities without control over the richest tax sources, leaving them dependent on transfers that rarely match the scale of their obligations.

This has become a rare point of consensus across political lines. Both Bharatiya Janata Party- and Opposition-ruled states have repeatedly demanded a greater share of central taxes. A large proportion of their revenues is locked into committed expenditures such as salaries, pensions, interest payments and subsidies, leaving little room to expand public services or invest in human capital.

At the same time, political compulsions have hardened. In large parts of rural India, the absence of sustained big-ticket investments has made welfare support not just an economic tool but a political necessity.

The real challenge, then, is not simply how to divide a limited pool of resources more efficiently, but how to enlarge that pool itself. So far, India’s spending gap has increasingly been filled with borrowing. “The bigger weakness is around the high interest burden of the government, which is related to the high debt level,” says Jeremy Zook, director of Asia Sovereign Ratings at Fitch Ratings, which continues to place India at its lowest investment grade of BBB–. “Interest payments take up nearly 25% of the government’s revenue, more than twice the median for BBB-rated [second lowest] countries. This significantly limits fiscal flexibility by constraining the government’s ability to spend on other priorities.”

Unlike other countries of similar economic size and ambition, India raises a comparatively modest share of its GDP through taxes and other revenues. It collects only about 20%, while even smaller economies like South Africa manage roughly 27%. In this position, India cannot fund hospitals and schools by endlessly reshuffling scarcity.

It must bring in more money and unlock a more inclusive growth for its young population.

Milking the Middle

Anujesh Kumar (name changed) is not poor, and he is not wealthy. He lives in the narrow, restless country in between.

At 49, he works as a senior manager with a real estate firm in Gurugram. His annual salary, before taxes, is around ₹28 lakh. This should place him among India’s comfortable classes. But in reality, much of that comfort dissolves before it even reaches his bank account.

A significant part of his income, over 20%, goes straight to the state in the form of taxes, if one also includes indirect taxes. By the time the money is his to spend, what remains is around ₹22 lakh. From that, he pays school fees for two daughters—private, because the government system feels too broken.

Kumar pays health-insurance premiums that rise every year, because his job will not allow him to sit in the corridors of a public hospital for months, waiting for a bed. He budgets for rent, transport, groceries, ageing parents and the fear of one medical emergency unravelling everything.

“Often I ask myself what I am paying taxes for,” says a disappointed Kumar. He earns roughly 11 times India’s nominal per-capita income, placing him comfortably above the threshold for the top 10% of earners. Yet nothing about his life feels extravagant. Nothing feels secure.

At the top of the economy however, the story looks very different.

India is now home to more billionaires than almost any country in the world, bar the US and China. Their numbers have risen sharply in the past decade, from a few dozen in the early 2010s to well over 250 today, according to a Hurun report. Their companies dominate stock markets and the public imagination. They pay large absolute sums in taxes, and yet, relative to their wealth, the burden they carry is far lighter than Kumar’s. The reason lies in how their money moves.

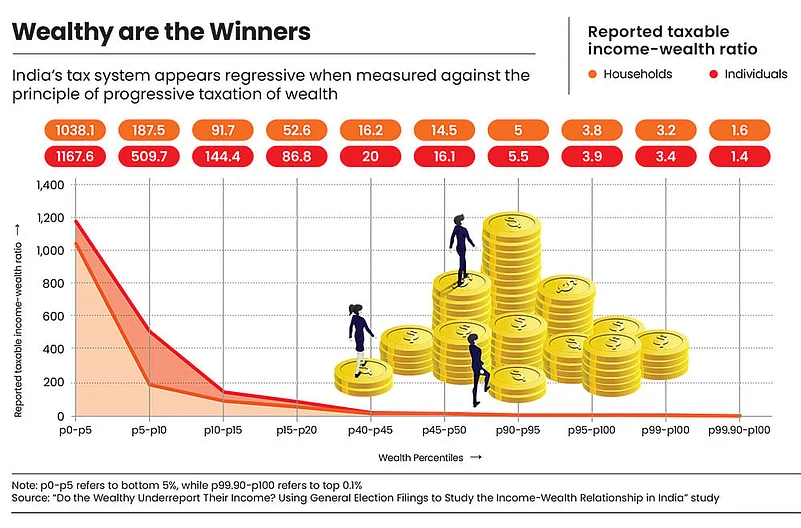

A large share of their wealth sits inside companies, not in personal bank accounts. The profits their companies make do not always show up as personal income, because profits can be retained instead of distributed. Dividends from company to owners and shareholders, are kept deliberately modest. Across India’s largest private listed firms, dividend pay outs are barely a fraction of the value of their equity assets, hovering around well under 1% for many top companies, notes Ram Singh, director, Delhi School of Economics, in his study “Do the wealthy underreport their income?”

“One of the consequences of tax avoidance is that dividend pay outs by Indian companies are meagre compared to most other countries,” Singh points out.

This matters because dividends, once paid, become personal income, and personal income is taxed. By keeping pay outs low, wealth stays parked inside corporate structures, growing quietly but never quite crossing over into taxable hands. “[Their] effective tax rate reduces mainly due to this shift, as dividends face taxation at highest rates up to 39%, while long-term capital gains are taxed differently and taxed only when realised. Also, in India, unrealised profits on shares are not taxable,” says Prashant Bhojwani, a corporate-tax expert and partner with BDO India, an accounting firm.

As opposed to this legal architecture of avoidance, there is also a messier route that many choose. Officers of the Indian Revenue Service admit that the agricultural-income exemption has, over the years, turned into a convenient tax shelter. High-income individuals, especially in cities like Delhi and Mumbai, have been reported to purchase agricultural land with no real intention of farming. Their primary professions have nothing to do with the soil, yet portions of their income begin to appear, on paper, as “farm earnings”.

The evidence already sits with the government. In an early compliance audit of direct taxes, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) examined a sample of 6,778 cases of claimed agricultural income. Delhi, strikingly, accounted for the second-highest number of claims that were ultimately disallowed. But the story does not end there. In a total 1,527 cases, agricultural income was allowed without adequate documentation or proper verification of supporting records, according to a report by the CAG.

“In cases where individuals earn both agricultural and non-agricultural income, it is remarkably easy to blur the lines between the two,” explains Akhilesh Ranjan, former member of the Central Board of Direct Taxes.

Media reports of celebrities and high-profile professionals increasingly buying farmlands suggest the problem is no longer marginal. Yet the Centre consistently shifts responsibility to state governments, citing their constitutional right to tax agricultural income. “Taxation of farm income constitutionally is a state subject. It is open to the states to levy this tax,” former finance secretary TV Somanathan told Outlook Business in an earlier interview.

Policy experts, however, say this deflection is driven less by constitutional restraint and more by political convenience. In a country with nearly 30 states, and where significant shares of legislators are themselves landowners, taxing farm income is politically combustible.

This system of convenient tax avoidance and evasion produces an odd result of a regressive tax system. Wealth expands. But tax liability does not rise in proportion. In fact, Singh’s study shows that as people become wealthier, the share of tax they pay compared to their wealth keeps shrinking. For those at the very top, income tax often amounts to around 1% of their total wealth. For the ultra rich, it falls even further to fractions of a per cent. The middle, meanwhile, bears a heavier relative load, even after accounting for exemptions.

Does this regressive tax system serve the economy any good? The answer is no. It strains public finances by distorting fairness, overburdening salaried individuals who cannot conceal income and end up paying a disproportionate share of taxes for underwhelming public services and quality of life, driving many to seek better value abroad.

At the same time, the poor pay the price through crumbling schools and hospitals, and with limited scope of upward mobility.

Instead of promoting equity and broad-based growth, this structure deepens inequality and erodes trust in the state. “The cost of their avoidance is collective. It falls on public services, rural infrastructure and human-capital investments that India desperately needs,” says Rajesh Shukla, managing director and chief executive of People Research on India’s Consumer Economy, an independent think tank.

Stung by voter discontent after the last general election, the Centre has tried to please them with income-tax concessions and GST cuts that many see as politically timed.

The government has also raised capital-gains taxes on listed equity in a bid to soften the regressive tilt of the system, but this is unlikely to be a real solution because much of India’s richest wealth is built through lightly taxed or creatively structured gains that rarely show up cleanly on the tax roll.

Trust Breaker, Tax Break

Much before the Centre looked towards the middle class to stimulate the economy through consumption, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman placed her biggest bet on India’s richest. The wager was simple. Cut their taxes, free their hands and they would build the factories, laboratories and jobs that would carry the country into its next phase of growth.

So, when the corporate tax cuts were announced in 2019, it was framed as a turning point, a signal that India was open for serious business. “Back then, we believed we had to make our private sector competitive, especially against South Asian peers,” recalls Ranjan. “The idea was that this would spur capital and R&D investments that would benefit the broader economy”, adding that this unfortunately did not happen, possibly because of a host of non-tax factors inhibiting private investment.

Apparently, the tax cuts have been followed by a long retreat into safety.

Balance sheets were repaired. Debts were pared down. According to rating agency CareEdge, corporate debt came down significantly from 66% of GDP in 2017 to just over 50% after the pandemic. But new factories remain scarce, bold research bets rarer still. There has been no visible surge in hiring, no great reshaping of the industrial landscape. The tax break that was meant to unlock animal spirits seemed instead to have fed an instinct of preservation.

The Centre speaks confidently about demographic dividend and global leadership, but its balance sheet tells a harsher truth that there is not enough money to do everything, everywhere, all at once

So, in September 2025, Sitharaman urged the Indian industry, once again, to overcome hesitation and ramp up investment, noting that the government had delivered on tax reforms, foreign investment liberalisation and ease of doing business. Speaking at the annual symposium of the Indian Foundation for Quality Management, she said, “I have a basket of things on which the government has delivered…I hope there’s no more hesitation for the industry to invest further, expand capacities and produce more in India.”

Private investment has become the Achilles heel of India’s growth story, and even global rating agencies have begun to flag the hesitation. As Fitch’s Zook puts it, there is unease about the absence of “any meaningful acceleration in private capital expenditure, despite healthy corporate and bank balance sheets”.

Not everyone has missed the warning signs. The government’s own Economic Survey 2023-24 has acknowledged that something fundamental has broken in the transmission. “Results of a sample of over 33,000 companies show that, in the three years between FY20 and FY23, the profit before taxes of the Indian corporate sector nearly quadrupled. Hiring and compensation growth hardly kept up with it.”

Many believe this is also why the government had to offer such deep tax cuts to the middle class throughout the year, that is, to make up for what the private sector was not delivering. Former Union finance secretary Tuhin Kanta Pandey, in an interview with Outlook Business post the 2025 Budget, explained that corporate-tax relief was meant to nudge companies to share the gains with workers through better wages, rather than pocketing the entire upside. “If you are raising productivity, then wages must also reflect that growth,” said Pandey. “This is why we are also indirectly telling corporates that please raise wages.”

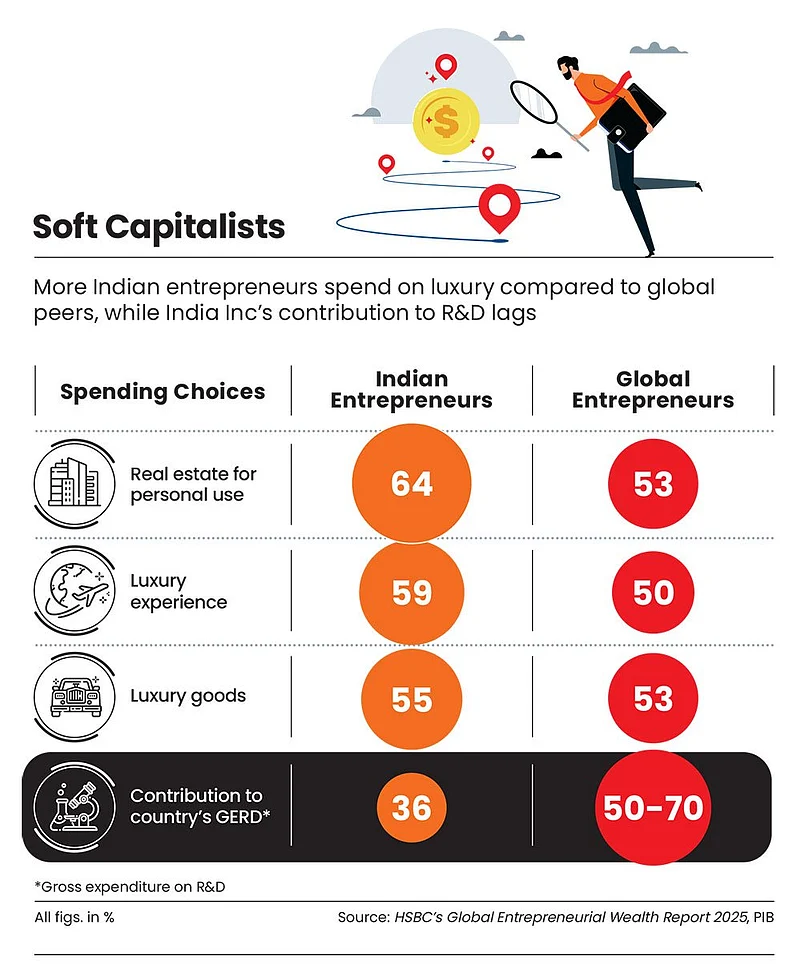

A similar story plays out with R&D investments, where Indian entrepreneurs are increasingly blamed for refusing to grow their spending on cutting-edge research that could give the country an edge in a rapidly evolving global economy. Yet what has grown instead is something else entirely: a culture of luxury.

In India, wealth is rarely quiet. As many as 64% of wealthy Indian business owners, according to HSBC’s Global Entrepreneurial Wealth Report 2025, park their personal wealth in real estate for their own use, compared to a global average of 53%. Their appetite for visible indulgence is stronger too, as they are likely to spend 59% on luxury experiences versus 50% globally.

This culture of conspicuous consumption routinely comes into public view, especially through the over-the-top weddings of industrialists that dominate headlines.

Much of India’s wealthy elite has turned inwards, focused less on building the next big thing and more on protecting what they already possess. Whether this reflects a fading appetite for risk, once the defining trait of entrepreneurship, or an obsession with securing dynastic futures is a question only they can answer.

Harsh Goenka, chairman of RPG Enterprises and one of India’s top industrialists, has shared his thoughts bluntly. “Gone are the days of sweating over P&Ls [profit and loss statement] and capex plans. Modern scions believe in passive income, active vacations and aggressive networking at yacht parties,” he wrote in a column for The Economic Times in February last year. “No labour strikes, no messy operations, no innovation headaches. Just a steady inflow of wealth, managed through mutual funds, private equity and hedge-fund brunches in London, with a long weekend in Courchevel to discuss asset allocation.”

Policy advisers appreciate Goenka’s truthful admission. Sanjeev Sanyal, member of EAC-PM, wrote on X, “Instead of leveraging their wealth to take bigger risks, they create ‘family offices’ and spend their time fighting with their cousins over the family art collection. Their parents need to insist on their heirs being on the shop floor rather than doing Ivy League MBAs that are no more than finishing schools.”

An economy does not grow because wealth exists. It grows because wealth is put at risk. Capitalists should be willing to lose money in the hope of creating something new. The rich should be brave enough to fail in public. Today, too much of India’s elite is not building the future but insuring itself against it. As many as 88% of Indian entrepreneurs, the highest in the world, believe preserving family control and legacy is a top priority, and therefore, they are also the most optimistic globally about their wealth continuing to grow, according to HSBC’s Global Entrepreneurial Wealth Report 2024.

But for a country, that needs big-ticket investments and public resources, this turn towards the comfort of simply multiplying wealth is now more of an economic problem than a cultural one. And it is draining the growth story the state wants to parade as evidence of national ambition and civilisational revival.

Time for a Wealth Tax

In 1991, India reinvented itself, stepping away from state control and into a market-driven economy. The old socialist order had stalled growth, so wealth was given room to expand and businesses were trusted to build the future. The bargain was that let the rich prosper, and they would pull the country along with them. But that promise came with a condition, that the state would remain strong enough to educate the poor, heal the sick, and provide security and justice.

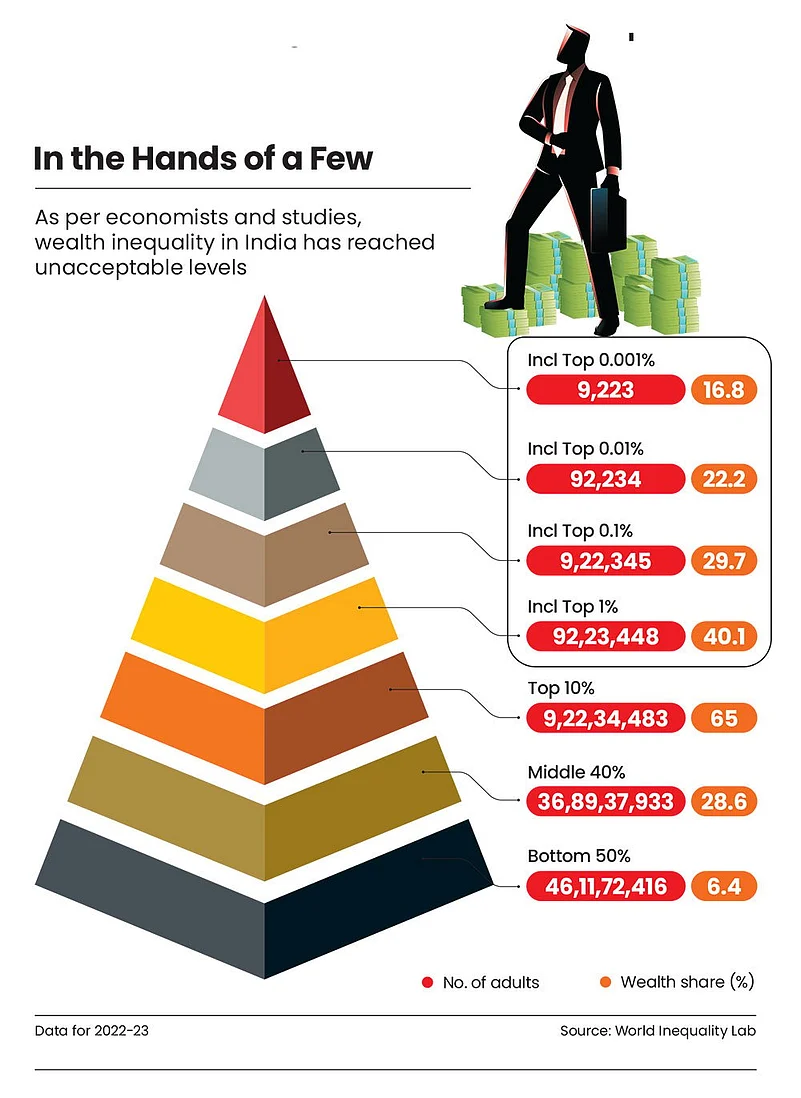

More than three decades later, India appears to be failing on both fronts. Union minister Nitin Gadkari, in a rare admission, expressed concern about the direction of India’s economic trajectory. Speaking at a public event, he warned that liberal economic policies could “centralise wealth in the hands of a few”, even as “the number of poor people is increasing”. The problem, he suggested, was not growth itself but its concentration.

Before him, French economist Thomas Piketty, working with Indian researchers, in a controversial report, warned that modern-day India risks building a new “billionaire raj”, where inequality would rival what the country saw under colonial rule. Their prescription is to impose wealth tax and inheritance levies on the “crorepatis”, and channel the proceeds into public services, into hospitals and schools, and begin undoing the centuries-old drift towards concentration of wealth.

Their proposal, affecting just 0.04% of the population, suggests that India could raise 2.7–6% of GDP annually through wealth and inheritance taxes. The exact details, such as exemption thresholds, progressivity, rates and inflation adjustments, would, they argue, need to emerge from a broader democratic debate.

Unsurprisingly, the proposal has met fierce resistance from economists working with the government. “Imposing wealth tax is not the solution for improving revenue and increasing growth,” says S Mahendra Dev, chairman, EAC-PM.

He argues that there are other instruments to reduce inequality and increase growth and welfare. “Creating quality employment, education and health provide better equality in outcomes,” adds Dev.

The lead author of the Piketty report, Nitin Bharti, pushes back hard. He argues that the very levers the government emphasises are now increasingly controlled by the private sector. “We are in a trap with high inequality and not enough public finances,” he says.

Bharti points out that India has seen an explosive expansion of private education and health care, an arrangement ill-suited to a low per-capita-income country. “Poor investment on the children of the bottom 90% relative to the top 10% will ensure this rich-poor divide exists in future as well,” he warns.

Yes, there are valid concerns. Chief Economic Adviser V Anantha Nageswaran has cautioned that a heavy levy on wealth or inheritance could spur “capital flight”, especially when global money moves at the slightest provocation and India is still trying to ramp up investment. Recent headlines about industrialists reportedly leaving countries such as the UK following tax-hike proposals only add to that fear.

But proponents counter that this anxiety is overstated. A well-designed package of wealth tax and inheritance taxes would target net wealth, regardless of where the underlying assets are held. In case of flight of individuals, global tax authorities are already using “exit taxes” to address exactly the kind of flight some fear.

“Even though exit taxes have not been a great source of revenue according to academic literature, they are certainly useful if the goal is to simply discourage renouncing citizenship for tax purposes alone,” says Rishabh Kumar, a wealth economist, who teaches economics at the University of Massachusetts.

“If the risk of capital flight was large enough, then we should have already seen all the richest people in the world move to low-tax jurisdictions like Dubai, Singapore and Monaco,” he adds.

A modest tax rate on wealth, even as low as 2%, Bharti argues could instead force wealthy asset holders to put dormant fortunes to work.

According to Knight Frank, a global real estate consultant, the combined wealth of Indian billionaires now hovers around $950bn, placing India among the top three globally. This speaks volumes about how much wealth is sitting idle in a country that craves for productivity.

The real difficulty has always been in designing a viable tax on wealth. India has tried before, both wealth and inheritance taxes once existed, but they failed largely because of weak implementation and meagre returns. Even advanced economies have struggled with such levies. Yet the context today is markedly different. This is an era shaped by rapid technological change, one that threatens to displace labour, widen inequality and generate instability unless low-income workers constantly upskill.

It is in this shifting landscape that the discussion on wealth taxation gains fresh urgency. The Economic Survey itself warns that governments may eventually need to tax the profits generated from the replacement of human labour with machines. If technology is imposing new burdens on the poor, it is only reasonable that the state also explore how technology can make wealth taxation feasible.

“Technology now allows what is essentially triangulation,” says Ajit Ranade, economist and senior fellow at the Pune International Centre, a think tank. “You can look at an individual or entity through multiple lenses and piece together a reasonably accurate picture of financial income or wealth, and then design a workable tax. We have to start somewhere, because extreme inequality is not healthy for any economy.”

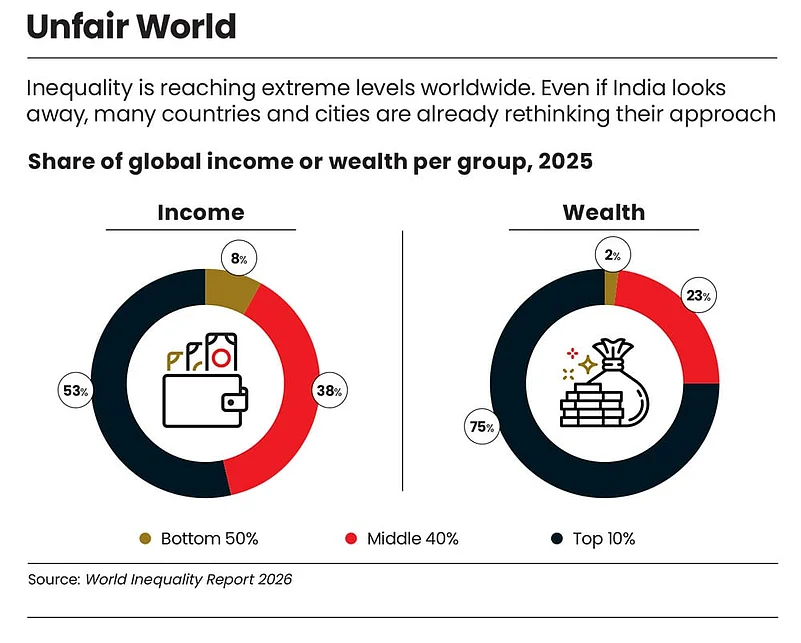

Indeed, and that is why the global mood is shifting. Cities long seen as strongholds of capitalism are now also backing higher taxes on the rich. In New York, the election of Zohran Mamdani as mayor on a platform of higher taxes for the wealthy has sent a clear signal to the world.

In the Global South, Brazil used its G20 presidency to put a proposal for a minimum wealth levy on the agenda, prompting talk of a 2% floor on billionaire wealth to raise revenue and curb extreme concentration.

In India however, the challenge still runs deeper than technicalities. Taxation is, ultimately, a political choice. Disclosures on electoral bonds show that corporate donations to political parties remain alarmingly opaque, with nearly half flowing to the ruling party.

So, when the same elite whose wealth may be taxed also wields political influence, the question of making them pay becomes more political than economic.

Realise the Size

For years, the idea of taxing the rich to fund human development has remained trapped in the legend of Robin Hood, reduced to the caricature of stealing from the wealthy to give to the poor. That narrative, however, now misguides a country edging towards instability at a time when its neighbours—Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka—have already shown what instability means.

The government may be alert to the fiscal leakages baked into the tax system, yet it remains uncertain about whether it can bite the bullet on wealth and farm-income taxation. Despite the resistance, some believe the moment will arrive, if not today, then inevitably tomorrow. As French author Victor Hugo once famously said, “No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come.”

India chose the path of a mixed economy, and rightly so. It needs the firepower of businesses and private investments to fuel its ambitions of becoming a developed nation. But when one half of the mix prospers without giving back in proportion, the other half shrinks in size.

Millions, who depend on the state for education, health, security and mobility, feel left out today. And so, when the country pours billions into bets like semiconductors, it attracts strong criticism for compromising on its human capital. A state chasing Viksit Bharat carries multiple obligations at once yet is routinely faulted for prioritising one over the other.

In a system where resources are thin and the tax base narrow, every choice feels like a trade-off. It is only fair, then, that the government recognises the scale it was always meant to have. A state that remains small by design can neither build human capital fast enough nor support the aspirations of a young population. In the end, size matters.

Note: By the time this story went to press, the government in a press release on December 29 said India has overtaken Japan to become the fourth-largest economy with a size of $4.18trn.