River targets tenfold turnover growth by 2028, planning new products, stores, and manufacturing plants

Current Bengaluru facility produces 3,000 units/month; $120–130M capital required for next expansion phase

EV two-wheeler penetration in India: 6.9% overall, ~20% within scooter segment

Bengaluru-based electric two-wheeler maker, River, is eyeing over tenfold increase in turnover by March 2028. The start-up is looking to ramp up product portfolio and bolster sales network across the country. It has recently launched its first North India store in Delhi and the latest iteration of its electric scooter, the Indie Gen 3.

The EV scooter maker already has 34 stores across India, including in Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, Pune, Kochi, Coimbatore, Patna, and Hubli. It is now focusing on markets like Punjab, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Gujarat, with the monthly sales of approximately 20,000 units and a turnover of around ₹1,200 crore.

River is now targeting ₹500 crore in sales revenue and the launch of two new products by March 2027. “We will launch our third product when the network reaches the 350 outlet mark in 2028. By march 2028, we will be at ₹1,200 mark,” Aravind Mani, cofounder and CEO of River told Outlook Business.

Mani assures that the start-up’s entire sales network will be fully supported by service centres. Currently, the EV maker is in discussions with several state governments to establish a greenfield manufacturing plant to boost its production capacity.

Its Bengaluru facility produces around 3,000 units per month. He also notes that the company may need approximately $120-130 million in capital for its next phase of growth. So far, the start-up has raised around $70 million from a group of investors, including Yamaha, AI-Futtaim Automotive, Lowercarbon Capital, Toyota Ventures, and Maniv Mobility.

The start-up plans to launch an IPO in the next 3-5 years.

EV Penetration Numbers & Trends

EV penetration in India was 7.8%in FY25, a slight increase from 7.1% in the previous year. The market is seeing steady growth, with the government aiming for a 30% EV share of the total vehicle sales by 2030. Of these, Mani says that four-wheelers are not witnessing a strong growth in EV adoption.

Sale of EVs in India went up from 50,000 in 2016 to 2.08 million in 2024 as against global EV sales having risen from 918,000 in 2016 to 18.78 million in 2024. Thus, India’s transition has been slow to start, but it is picking up. India’s EV penetration was only about one – fifth of the global penetration in 2020, but has picked up to over two-fifth of the global penetration in 2024.

“If you look at total penetration, electric two-wheelers make up about 6.9% of all two-wheeler sales. But since nearly all are scooters, the EV penetration within the scooter segment alone is around 17%, which has now risen closer to 20% this year,” says Mani.

Last year, Mani asserts that those 1.2 million electric scooters came from a base of about 7 million scooters and 19 million total two-wheelers sold. Out of 19 million two-wheelers, 7 million were scooters, and 1.2 million of those were electric.

The reason behind higher diversification in scooters is that two-wheelers are primarily used for intra-city travel. “The average scooter usage in India is about 25–30 km a day, and most good electric scooters today have a range of 100 km, which means that they need charging only once every three days. So, range anxiety isn’t really an issue,” he explains.

He also points out that motorcycles are less likely to get electrified due to price and limited range suitability. A basic motorcycle priced at around ₹70,000–₹80,000 cannot support an economically viable electric conversion, as EVs generally cost 25–30% more than comparable petrol models.

For instance, a TVS N-Torq 125cc scooter priced at ₹1.2 lakh can justify an electric version at ₹1.5–₹1.6 lakh, but the economics don’t work for entry-level motorcycles.

As a result, the roughly 5 million low-end 100cc motorcycles — the largest chunk of India’s two-wheeler market — are unlikely to electrify anytime soon. Hence, for now, scooters remain the most practical use case for electrification.

Technology, Market Dynamics & Batteries

The Indian market has witnessed a huge improvement in battery life and gaining consumer confidence. Earlier, there were doubts about degradation and safety, but now most OEMs provide 5-8 years of battery warranty.

Another interesting factor is the economics of running an electric vehicle. Even though the upfront cost is higher, the River founder says the running cost per kilometre is one-fourth that of petrol vehicles. This is the reason why high-usage customers like delivery riders, fleet operators, and gig workers find EVs financially attractive.

“Many OEMs believe that battery costs will decline enough to make EVs naturally competitive by 2026-27. Battery costs have already dropped from about $150 per kWh to approximately $100 per kWh. And it may further go below $70 per kWh in the next two years,” he says.

When it comes to resale value, electric two-wheelers are still catching up. ICE (internal combustion engine) vehicles have a well-established resale ecosystem, whereas EVs are relatively new. “Over the next few years, as the secondary market for EVs matures, this will become less of a concern”.

Policy, Infrastructure & OEM Strategies

Mani further acknowledges that the government’s role in the surge of EV adoption across the country. According to him, the FAME II scheme and other state-level incentives have made electric vehicles financially viable during the early adoption phase.

However, as those subsidies start to phase out, Mani says that the market now has to sustain itself through product innovation, cost efficiency, and customer experience – the next big test for OEMs (original equipment manufacturers).

Besides EV adoption, the government is also working on policies around battery recycling, swapping infrastructure, and production-linked incentives (PLI) for cell manufacturing to reduce import dependence, especially on China for lithium cells.

Even as the government pushes forward with policies to boost the overall EV ecosystem, the practical infrastructure for charging remains uneven, with two-wheelers faring better than larger vehicles and fleets. Companies like Tata Power, Statiq, and ChargeZome are expanding charging networks, but utilisation levels are still low.

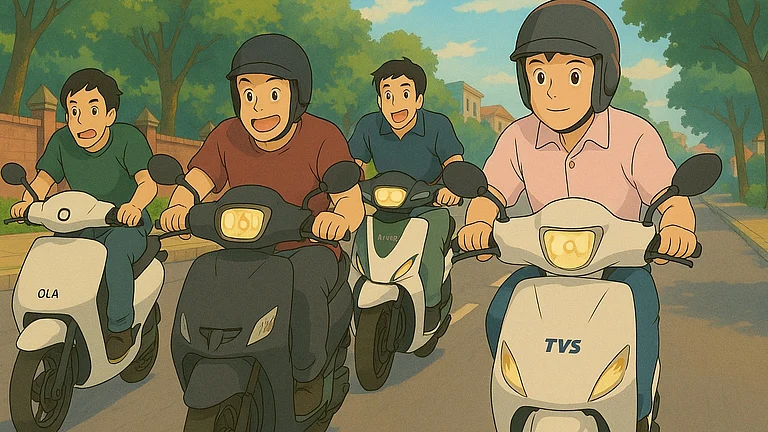

On the OEM front, legacy players like Bajaj, TVS, and Hero Motors are much more aggressive today. “They are expanding their EV portfolios and retail presence. For example, TVS has managed a strong transition with iQube series. Bajaj is also ramping up its Chetak production,” he says.

“Among new-age companies, Ola Electric continues to dominate in volume, though it faces pressure to maintain quality and service standards as it scales. Ather, on the other hand, is positioning itself as a more premium and reliable brand. Both are expanding into new segments — Ather recently launched a family scooter, while Ola is entering motorcycles,” he adds.

In addition, international players like Honda and Yamaha are also expected to join the EV race by 2026, once localisation and cost structures stabilise. He believes that their entry could significantly accelerate the market’s maturity.