There is scope of improvement in speeding up the signing of PPAs, grid infrastructure and last-mile reforms.

Offshore wind is 2.5–3x more expensive than onshore wind but it can play a role in the energy mix post-2030.

Continuous improvements in turbine design, AI-driven digital twins, automation, robotics, drones and smart monitoring are reducing costs and improving efficiency in the wind energy sector.

Wind’s higher capacity utilisation factor of up to 45% makes it more reliable for 24x7 power compared to solar.

Suzlon is positioning itself not just as a turbine manufacturer but as a green energy transition partner, helping customers with integrated FDRE solutions.

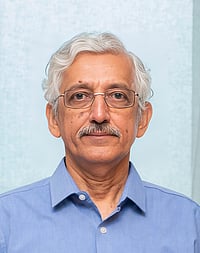

Suzlon, with nearly 40% share of India’s wind energy market, stands at the forefront of the country’s clean energy transition. In an interview with Outlook Business, Vice Chairman Girish Tanti highlights the vast potential of wind power, its growing importance in India’s energy mix and the critical challenges the sector must overcome.

He also shares insights on offshore wind deployment and explains why wind, with its unique advantages over solar, will play an increasingly pivotal role in achieving India’s Viksit Bharat vision.

What is the wind energy potential in India, and to what extent are we currently harnessing it?

We are among the few countries in the world to set such an ambitious decarbonisation goal—achieving nearly 50% of our energy from renewables by 2030. We have already met 50% of renewable energy capacity five years ahead of schedule. In absolute terms, our target is 500 GW from renewables, with 100 GW from wind. In wind energy alone, we have crossed the halfway mark, reaching 51 GW.

Unlike earlier, the market today has three distinct demand segments: government procurement, the commercial and industrial (C&I) sector and PSUs. Demand for both wind and solar is strong, and we are well positioned to achieve our targets.

India has just crossed the halfway mark to achieve its 2030 wind capacity target but needs to install another 49 GW. Meanwhile, our annual addition stood at 3.25 GW last year. In which areas, do we need to improve to accelerate progress?

On the project execution side, there are three key levers that can accelerate this journey. First, we must reduce the time between bidding and the signing of power purchase agreements (PPAs). Currently, there is a backlog of about 40 GW.

The second opportunity lies in strengthening grid infrastructure. Renewable energy projects need to be developed in a distributed generation system. Traditionally, grids designed for centralised generation and distribution. Wind and solar projects are often located in remote areas, far from demand centers, making transmission a critical challenge. To address this, the government is implementing the Green Corridor initiative—building new grids specifically designed to integrate wind and solar. There is an opportunity to speed up those activities If grid infrastructure is developed faster, achieving the 500 GW target will not only be certain but could even happen ahead of schedule.

The third lever is last-mile project execution. States have an opportunity to introduce reforms related to land acquisition, right of way (ROW) and local law and order. Streamlining these processes will enable faster on-ground execution and ensure that projects move smoothly.

Reforms are needed more on the execution side but when all three levers are put together, the country largely seems to be on track for 500 GW.

India has installed over 50 GW of wind capacity compared to about 122 GW of solar. The momentum clearly favours solar. Why is wind not receiving equivalent policy and investor focus, despite its higher capacity utilization factor (CUF)?

The target is in the ratio of 1 is to 3. As long as we maintain that ratio, we are on track. These numbers have been derived through a scientific approach, considering resource allocation, adequacy, cost of energy and execution feasibility. The right mix of non-fossil sources will ensure the lowest possible cost of energy for the end consumer.

Solar naturally has a higher share due to its advantages, but wind also brings unique strengths, which is why its share must grow faster. Going forward, wind will play an increasingly important role in our grid system, and there are several clear reasons for that.

India’s power demand has two daily peaks: one in the morning before people leave for work and a larger one in the evening when households switch on lights, fans and appliances. Unfortunately, solar cannot meet these peaks, as they occur before sunrise and after sunset. Wind, however, closely matches this demand pattern, generating more power when demand is high and less when demand is low.

Seasonal demand peaks during the monsoon, summer or winter broadly align with wind generation patterns. This high correlation between wind patterns and demand makes wind energy valuable for India’s power system.

So, a large portion of wind energy generated is consumed immediately, without the need for storage. In contrast, solar power faces a different challenge. We have already reached a stage of zero pricing in some regions during the afternoon. Solar generation is so high that demand cannot absorb it. This means that despite producing electricity at around ₹2.5 per unit, there are times when no buyers exist, even at zero cost. It has happened in many countries. India is going through that phase right now.

This is why battery storage tenders are becoming more common which adds a significant cost. When we compare the cost of pure solar, solar plus storage, pure wind and wind plus storage, wind emerges as the least-cost option for meeting 24x7 demand. By 2047, as part of Viksit Bharat, the share of wind in the new energy system design will significantly increase.

It is also important to note that the cost of carbon is not yet factored into today’s energy pricing. Once carbon costs are integrated, the gap between fossil fuels and renewables will widen further. Pollution from conventional fuels will inevitably carry a cost—someone must pay to clean it up. At present, that cost is invisible in energy pricing, but as markets mature, it will become a reality, making renewables even more competitive.

Given the clear advantages of wind energy, do you see increased policy focus and increased investment in wind energy in the coming years?

The business case for wind is very strong, and things will only improve further. If wind is the cheapest source for consumers, then naturally it will prevail, because ultimately, consumers decide what works.

As the share of renewables in the grid increases, the role of wind will grow. At smaller levels of penetration, its impact on pricing is limited, but once it reaches significant levels, it starts to influence market pricing. In terms of actual generation, renewables account for closer to 15–20% of total electricity in kilowatt-hour terms. Solar has a lower CUF of around 27–32%, while wind is somewhat higher, with best results reaching 40–45%. This means wind’s utilisation is about 1.5 times higher than solar.

By 2030, renewables may contribute around 25% of actual energy consumption. Solar may have three times the installed capacity, but it will generate only about double the energy compared to wind. The real metric we must track is the share of each source in the energy actually delivered to consumers. Capacity build-up is important, but from a consumer’s perspective, what matters most is who can generate energy when it’s needed, at the lowest possible cost.

The National Institute of Wind Energy has identified a potential of about 70 GW that is spread across 16 offshore zones of Tamil Nadu and Gujarat coasts. What are the some of the challenges hindering wind capacity expansion in coastal and offshore zones?

Countries go for offshore wind either because they are land-constrained or because the wind conditions at sea are stronger and more consistent than on land. This is why most large offshore developments have happened in Europe—the North Sea, Germany, the Netherlands, Scandinavia—where offshore wind potential is high, making the economics work.

In India, the total onshore wind potential is about 1,165 GW. Current installed capacity is around 50 GW. We have utilised only about 4–5% of our potential. Contrary to the perception that land is scarce, about 96% of viable wind sites are still available.

The cost of offshore wind is typically 2.5 to 3 times higher than onshore, due to complexities such as underwater cabling, floating foundations and marine infrastructure. Moreover, the difference in wind potential between land and sea is not very high in India, since the Indian Ocean is relatively calm compared to, say, the North Sea. This makes the cost gap significant—offshore wind here would cost over ₹9 per unit, while onshore is far cheaper. So, large-scale offshore projects are not immediately viable.

However, the government has identified sites for demonstration projects, much like how land-based wind started in the 1990s. To make them attractive, the government has committed viability gap funding (VGF) to cover the cost differential.

These projects are complex, involving multiple ministries, environmental clearances and marine considerations. Realistically, India’s 2030 target of 100 GW of wind will be met almost entirely through onshore projects. Offshore may play a role post-2030, as part of the Viksit Bharat vision.

When India began wind development in the 1990s, the estimated potential was only 300–350 GW. Today, it has tripled to 1.1 TW, not because wind has increased, but because technology has advanced, enabling generation even at lower wind speeds. This trajectory will continue, and over the next 20–30 years, offshore wind may also become commercially viable.

MNRE has introduced Approved List of Models and Manufacturers (ALMM) for wind energy requiring manufacturers to source key components from domestically. What challenges do you see and how is Suzlon preparing to align with these mandates?

Last year, the wind sector had an average local content of about 64%, while at the company level we are already above 80%. Wind manufacturing has been building in India for nearly two decades, so the base is strong. By comparison, other industries are much lower—solar at around 20%, and battery storage or EVs at only 15–17%, still heavily import-dependent.

The government’s aim is to strengthen this further so that by 2030, India can reach 80–85% local content at the national level. This is achievable, since wind manufacturing does not face constraints like rare earth material dependency seen in other industries. The technologies, designs and supply chains are largely manageable within India.

At Suzlon, we currently have 15 manufacturing plants, spread across all eight key windy states—Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh.

At the national level, India has an integrated wind manufacturing capacity of about 20 GW annually, while current installations are only 5–6 GW per year. This means we already have nearly 4x manufacturing capacity available, with almost 50% of it being exported.

According to the latest Global Wind Energy Report, India is expected to account for about 10% of the global wind supply chain by 2030, representing an opportunity of $15–20 bn.

It is one sector where India can proudly say we are truly Atmanirbhar. We have our own IP, globally benchmarked technology and products that compete at the cutting edge in terms of performance, reliability and cost efficiency. Our progress is also not heavily dependent on geopolitics, which is a major advantage.

Are there any technological innovations in the wind turbines globally that India should adopt?

There is a general belief that imported is better but India has proven that in wind otherwise. Suzlon turbines have been running successfully in 17 countries for the past 15–20 years. These are high-value, high-tech products operating across both the Southern and Northern hemispheres, including advanced Western economies, competing at par with the global best.

A wind turbine is a highly complex engineering marvel, involving mechanical, civil, electrical, electronics and aerodynamics. The blades we manufacture in India have a wingspan larger than that of an Airbus A380. At its core, Suzlon is a technology company. Globally, only a handful of wind companies have survived the past three decades. Many others have disappeared due to the challenges of this industry.

Unlike other industries, wind turbines cannot be standardised worldwide—conditions differ drastically. For example, in extreme cold conditions in Northern Hemisphere projects, blades face icing at –30°C, requiring advanced de-icing technology, and in high moisture zones, there is a risk of short circuit. Similarly, in coastal areas, high salinity causes corrosion, requiring anti-rust protection.

Each geography demands customised solutions. That is why engineering expertise is critical in this industry. India’s wind technology is world-class, proven and competitive globally.

How is India leveraging technology and AI across the wind energy value chain to reduce costs and enhance performance?

Our focus is to consistently reduce the cost of wind energy generation year after year, whether through technology, supply chain improvements or performance optimisation.

What makes this even more exciting today is the role of AI, which is opening new frontiers across the value chain. At the design level, we are using AI for advanced simulations through digital twins, allowing us to test multiple scenarios, optimise outcomes and sharpen engineering designs without the high costs of physical trials.

In manufacturing, AI, automation and sensing technologies are driving productivity, enhancing safety, reducing waste and improving efficiency. We are actively implementing the integration of robotics in our operations.

We have started using drones for project design and monitoring. AV tools, geotagging and geoscience mapping help us plan and execute projects more effectively, enabling smarter, sharper and more efficient designs.

Every innovation must contribute to one of three outcomes—reducing costs, enhancing performance or delivering greater value to customers.

Beyond your current verticals, what are the next frontiers Suzlon is targeting in the next 3–5 years?

Right now, customers are asking us: “Can you also provide a full FDRE solution with solar, storage and design support?”

We’ve begun helping customers design such integrated solutions, positioning ourselves as a partner in their green transition. Energy management will play a central role as we expand in this direction. But there are no fixed timelines yet. We’re experimenting, standardising approaches and will make formal announcements once ready. What matters most is keeping our customers with us on this journey.

A recent Teamlease RegTech report said that there are over 2000 regulatory compliances that solar projects have to deal with. Is the situation similar in wind projects? If yes, how do you navigate this challenge?

All said and done, today the power sector is a regulated market. There are many aspects to address, and the government is working to simplify them. Just last week, we had meetings where the government asked industry for suggestions on how to improve the sector.

There is strong support across the value chain to enable the green transition. Naturally, the scale and speed bring challenges. India must manage them differently, taking all stakeholders along. Key priorities include energy security, reliability of power supply and affordability. While challenges remain, forums for engagement exist and issues are being fast-tracked.

What is the role of wind data in efficiency of project execution? Are we strengthening weather forecast to ensure better data collection?

Currently, we are required to provide 15-minute average forecasts as part of the grid management system, and the supporting technologies are steadily improving. AI is playing a significant role in enhancing forecasting accuracy. It’s a complex subject, but one that is well within our ability to manage and the tools and methods are only getting sharper.