For the developing world, global climate negotiations have long fallen short. The story has remained unchanged and predictable over 29 editions of the planet’s foremost climate convention, the Conference of Parties (COP). As an increasingly turbulent world steps into Belém, Brazil, there are doubts about whether COP30 will be any different from Baku and the 28 other COPs before it.

Last year at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, developed countries had agreed to mobilise $300bn annually by 2035, a fraction of the $1.3trn developing countries needed to implement their climate action pledges. Though not unexpected, Baku’s fiasco looked much the worse for its “finance COP” billing. Unmoved by that failure, COP30 is being heralded as the “first COP of implementation”.

The Global South, in particular, must hope it is, because the credibility of the global climate process itself is pegged on Belém succeeding where Baku failed.

“The discussions are expected to revolve around what is really achievable. There will likely be a reality check: can we actually meet 2050 net-zero goals? The balance between energy transition and energy security will remain central,” says Gauri Jauhar, executive director, global energy transitions and clean-tech consulting, S&P Global Commodity Insights, a market-analytics firm.

In the run-up to the negotiations, developing countries have spelt out their priorities. At a climate summit convened by UN Secretary-General António Guterres and Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva on the margins of the 80th UN General Assembly in September, they pushed for adaptation, resilience and loss-and-damage measures to be woven into national climate pledges.

The summit noted that the technologies to decarbonise energy, transport and industry, protect forests and build resilience already exist. What’s missing is the means to scale them.

Echoing this, the implementation forum organised by the COP30 presidency during Panama Climate Week in May this year stressed promoting tangible actions on climate finance, technology transfer and carbon-market development. The emphasis this time is not on fresh promises but on mechanisms that can make past promises work.

The Finance Reality

The finance required for a genuine energy transition is staggering. Private Fantasies, Public Realities—a report by Oil Change International, an advocacy organisation—estimates that the world will need $5.7trn every year by 2030 to make it happen. Yet barely 38% of that was actually tracked in 2023–24.

Against this backdrop, last year’s COP managed to nudge the $100bn pledge up to $300bn. In reality, even that exists largely on paper. “History shows that pledges don’t always materialise. Even the $100bn commitment took years to take shape, and even then the money never fully came through,” says Jauhar.

India has been forthright in calling out this imbalance. The New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance, announced at COP29 in Baku, was described as “grossly inadequate”, “incomplete” and an “eyewash”.

At the heart of India’s demand is clarity on the definition and delivery of finance. “Climate finance flows must be grant-based or concessional, not private equity or commercial capital flows,” says Leena Nandan, former secretary, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and deputy leader of the Indian delegation at COP29.

At the 62nd session of the Subsidiary Bodies (SB62) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Bonn, India-led coalitions—G77+China, the Like-Minded Developing Countries, the Alliance of Small Island States, Least Developed Countries and the African Group of Negotiators—joined forces to raise the issue of accountability in climate finance. SB62, or the Bonn conference, is the annual precursor to the COP.

India’s Climate Dilemma

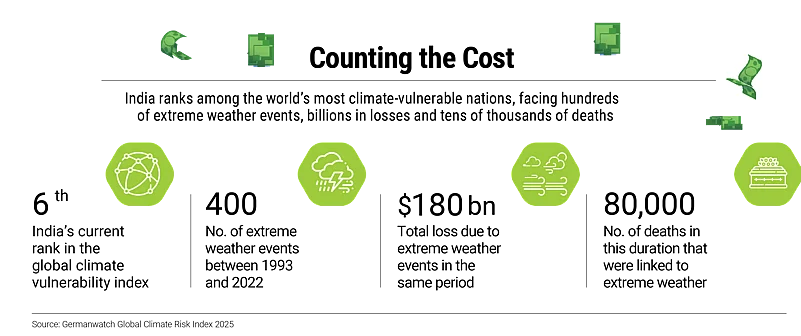

The finance vacuum has direct and devastating consequences for countries like India, which now ranks sixth globally in climate vulnerability, according to the Germanwatch Global Climate Risk Index 2025. Tracking extreme weather events between 1993 and 2022, it recorded more than 400 such incidents in three decades, causing losses of nearly $180bn and at least 80,000 deaths.

According to a 2022 report by World Weather Attribution, a scientific research initiative, climate change made early heat in India and Pakistan 30 times more likely. The Climate Transparency Report 2022 noted that heat exposure in 2021 wiped out roughly 167bn potential labour hours, costing India about $159bn, or 5.4% of its GDP.

Even the Economic Survey 2024–25 concedes that effective adaptation demands a many-fronted approach: policy action, resilient infrastructure, research and finance.

Yet adaptation finance remains nowhere near the need. Even as international funding inched up from $22bn to $28bn in 2022, the requirement stands closer to $359bn a year. More than 60% of what arrives comes as loans, loading fresh debt onto economies that are already struggling.

“There needs to be a concerted international effort to ensure that developing countries apply pressure on developed nations to meet their commitments,” Abhishek Acharya, director, MoEFCC said during a roundtable organised by Climate Trends, an environmental insights platform, ahead of COP30.

Establishment of the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) under the Paris Agreement has been neglected for six years after which countries agreed to commence a two-year work programme at COP28 to develop indicators for tracking progress, with the goal of finalising them at COP30.

So far, developing countries, including India, have not accepted the discussions on GGA as they have been limited to technical debates without being grounded in the realities of implementation. Therefore, indicators for ‘Means of Implementation’, such as finance, capacity building and technology transfer are critical as they show how climate action will actually be carried out.

“It is the biggest challenge that India is likely to face. Beyond the difficulty in providing the required data, it is tricky because the current indicators are too intrusive, asking countries to report how much they are spending across sectors and different stages of the adaptation cycle,” says Amrita Goldar, senior fellow at Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, a public-policy body.

“The indicators should be clear and categorical, but financial support for adaptation cannot become yet another reporting burden for developing countries,” says Nandan.

Bridging the Gap

The absence of accessible finance also chokes technology deployment. Funding for emerging solutions such as green hydrogen, carbon capture and nuclear power remains limited because they are deemed too risky. India has made progress in renewables, but battery storage still trails.

“Net zero will not be possible unless money flows into these higher-risk projects. These breakthrough technologies, essential for decarbonising hard-to-abate sectors, need heavy investment to become commercially viable. Financing has to support not just production but the entire ecosystem: midstream infrastructure, off-takers and replication of bankable projects,” says Jauhar.

The consequences are visible in daily life. “Without timely finance, access to technologies that reduce emissions, whether catalytic converters, retrofits or advanced clean technologies, gets delayed,” she adds.

It is a vicious cycle: scarce finance slows technology adoption, prolongs emissions and reinforces the perception of risk, raising the cost of capital still further.

“If such technologies were made readily available, emission reductions could have accelerated significantly. India will continue to emphasise this point: cleaner production technologies are essential for meaningful climate action,” says Nandan.

Progress in carbon markets has been similarly sluggish. Uncertainty over operationalising Article 6 of the Paris Agreement has denied India and other developing nations a potentially important source of finance. “At COP30, countries will seek clarity, but no new negotiations will take place,” says Trishant Dev, deputy programme manager, climate change, Centre for Science and Environment, a think tank.

India, meanwhile, has begun moving on its own. It has signed a bilateral carbon-credit pact with Japan and is developing a domestic market through amendments to the Energy Conservation Act. “In Brazil, the dominant agenda is expected to centre around operationalising Article 6, along with discussions on climate finance, addressing loss and damage and enhancing adaptation efforts,” says Anjal Prakash, professor, Indian School of Business.

Together, technology finance and carbon-market access will determine whether implementation finally shifts from intent to impact.

Decisions Must Translate

Progress has been slow, but India is tackling the challenge in its own way. The government has begun discussions with insurers on a nationwide climate-linked insurance scheme to speed payouts after extreme weather events. Yet domestic effort can only go so far when global willpower lags.

The crisis itself was created largely by developed economies, yet its sharpest blows fall on developing ones struggling to grow and adapt at once. For India and the Global South, COP30 must deliver three essentials: finance that is equitable, grant-based and time-bound; adaptation indicators that are transparent and practical; and carbon markets that actually function.

“India calls for enhanced technology transfer and capacity building to strengthen resilience, especially in agriculture, health and infrastructure,” says Prakash.

Last year, the talk was all about finance. This year, the how of it matters more. “It must decide on the mechanisms to actually operationalise that finance and its flow into projects on the ground,” says Jauhar.

There has been enough talk. COP30 must be about implementation and clear action, delivering the climate justice that India and the Global South have waited far too long to see. Otherwise, Belém will be Baku once again.