In 2011, Shravan Bhati, working with ex-ISRO scientist Dr. Ranendu Ghosh, identified that India’s scattered weather stations were limiting temperature data accuracy, a crucial factor for agricultural forecasting.

In 2023, Bhati, Ghosh, and Urmil Bakhai launched SatLeo to use satellite thermal imaging for real-time, high-resolution land surface temperature (LST) data, leveraging India’s newly liberalized Space Policy.

SatLeo’s ex-ISRO-led team is building satellites with MWIR and LWIR thermal cameras to replace ground-based guesswork, enabling applications from agri-insurance to weather prediction.

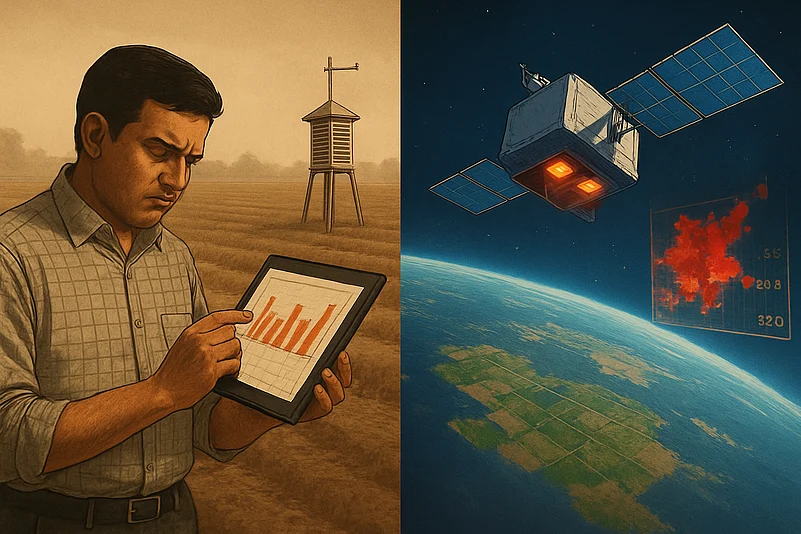

Back in 2011, Shravan Bhati armed with a Master’s in Geomatics and a string of ISRO-linked research projects was at the helm of a major government-backed initiative. The mission was ambitious: harness satellite data and AI to deliver precise agricultural advisories. Supported by a team of seasoned ISRO veterans, the project was breaking new ground in using space technology for farming.

Working with Dr. Ranendu Ghosh, a former ISRO scientist and technical advisor, they pinpointed that temperature data from the country’s scattered network of weather stations was limiting forecast accuracy. This finding became a pivotal step toward strengthening the precision of agricultural predictions in India, proving the project’s value as a catalyst for systemic improvements.

That pain point, frustrating, specific and systemic, sparked an idea. Could satellite thermal imaging solve what on-ground sensors could not? Bhati and his collaborators realised there was no scalable way to get high-resolution, real-time temperature data across vast agricultural belts. IoT sensors were too scattered, drones lacked range, and manual monitoring was a non-starter.

That insight would eventually power up SatLeo.

In 2023, Bhati teamed up with Dr. Ghosh and Urmil Bakhai to launch the space-tech startup designed to beam back thermal intelligence from orbit. The timing was perfect. India’s Space Policy 2023 had just thrown open the doors for private companies to build and launch satellites. The trio brought ISRO’s legacy with them and a mission to fix India’s broken climate data infrastructure.

Behind the sleek brand is a formidable engineering engine. SatLeo’s core team includes Amit Krulkar (Head of Systems), Arup Roy Chowdhury (Head of Electronics), and Rajesh Garvalia (Head of Power Electronics), all ex-ISRO scientists with deep technical chops. Their job: build satellites smart enough to read the planet’s skin temperature, cheap enough to launch at scale, and reliable enough to replace terrestrial guesswork.

“Temperature data is the bedrock of everything from agri-insurance to weather forecasting,” says Bhati, now CEO and Co-founder. “Our technology is focused on assessing land surface temperature (LST), often referred to as the 'skin temperature' of the Earth. This data acts as a base layer from which a range of other critical information can be derived. For instance, ambient temperature essential for accurate weather forecasting can be estimated from LST.”

The architecture is classic Earth observation: a payload (the camera), a satellite bus (which houses and powers it), and a launch vehicle. SatLeo’s payload is a thermal camera, tuned to pick up two specific bands of heat — MWIR (Medium-Wave Infrared) and LWIR (Long-Wave Infrared).

“Our satellites operate in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), approximately 500 kilometres above the Earth's surface,” explains Dr. Ghosh, now CTO. “These satellites are launched via rockets that follow a polar trajectory, allowing them to scan the entire surface of the Earth from pole to pole.”

LEO is not just a cool acronym. It is a battleground. As of December 31, 2023, India operated just 22 satellites in this orbital range. The US, by comparison, had deployed thousands. For India to scale its ambitions in space intelligence, defence and connectivity, it needs a lot more eyes in the sky.

“According to some estimates, laying terrestrial network infrastructure can cost nearly ₹10 lakhs per kilometre, making it economically unfeasible in remote or sparsely populated regions. In such cases, satellite communication (SATCOM) emerges as a highly viable and efficient alternative,” says Lt Gen Anil Kumar Bhatt (Retd.), Director General of the Indian Space Association (ISpA).

SatLeo’s choice of orbit is no accident. LEO satellites, which fly at altitudes between 500 and 2,000 kilometres, are ideal for high-resolution thermal imaging — the company’s core function. They are cheaper to launch, faster to update, and better suited to near-real-time observation than their geostationary cousins.

And the payload? It is all about the bandwidths. “Optical data, like what we see on Google Maps, falls in the 0.4 to 0.7 micrometre range,” explains Bhati. “Thermal infrared, on the other hand, starts at around 3 micrometres and extends up to 12 or even 14 micrometres. Within this thermal range, MWIR spans 3 to 5 micrometres and is often used for high-temperature targets, while LWIR spans 8 to 12 micrometres and is valuable for applications like night-time imaging, agriculture, defence and urban monitoring.”

By capturing both MWIR and LWIR on the same satellite, SatLeo sidesteps the usual cost-versus-performance trade-off. “We reduce costs, enhance efficiency, and offer greater value to the customers across sectors,” Bhati says.

And that is just the tech. The business model is just as carefully engineered. Bhati and his co-founders have done the maths. “If launching one of the satellites costs ₹10, we make sure it generates at least ₹1,000 in revenue over its operational life, typically about five years. Only then does it make sense for us and our investors,” they say.

SatLeo’s business model flips the usual space startup economics: for every ₹10 it spends on launching a satellite, it targets ₹1,000 in revenue over five years. This 100x revenue-to-cost ratio reflects a sharp focus on scalability, sector-wide applicability, and investor viability.

The economics are compelling and timely. India is eyeing a 44-billion-dollar space economy, and investors are hungry for proof-of-concept companies with government backing, commercial clients and frontier IP. In April 2025, SatLeo raised 3.3 million dollars in pre-seed funding led by Merak Ventures, with support from Java Capital, GVFL and Huddle Ventures.

According to Dr. Ghosh, the global agri-tech market alone is worth 400 billion dollars. “The specific datasets that we are capturing with our satellites are highly relevant for this sector,” he says. Capturing both MWIR and LWIR bands from a single satellite, he adds, is a technological edge that not only lowers costs and simplifies deployment but also boosts investor confidence.

And customers are buying in. Government ministries, especially in defence and agriculture, have begun engaging with SatLeo’s data streams. So have deep-tech and agri-tech companies like CropIn, SetuShots and Amnex, which currently rely on ground teams and IoT sensors to monitor fields. By switching to SatLeo’s orbital datasets, they can scale faster, cut costs and operate with greater precision.

In the space intelligence race, SatLeo is moving fast. Backed by ISRO and IN-SPACe, the startup plans to launch India’s first thermal imaging satellite by 2026, with initial testing scheduled for December 2025. The recently raised funds will go toward manufacturing, payload calibration and hiring new talent in data science and AI to bolster SatLeo’s analytics muscle.

It is not just about watching the Earth from space anymore. It is about decoding its temperature in real time, at scale and with precision sharp enough to change how we grow food, monitor cities and plan for war.