A year after Ratan Tata’s death, divisions have emerged within the Tata Trusts, which control a 66% stake in Tata Sons.

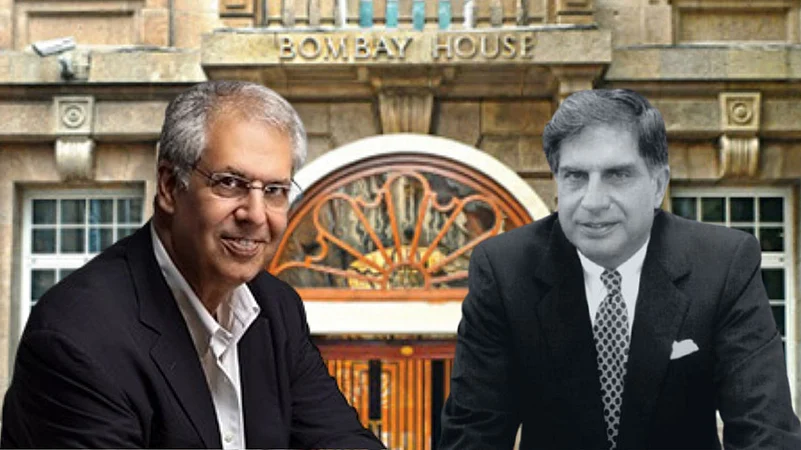

On September 11, trustees met at Bombay House to decide on the reappointment of Vijay Singh, their nominee on the Tata Sons board.

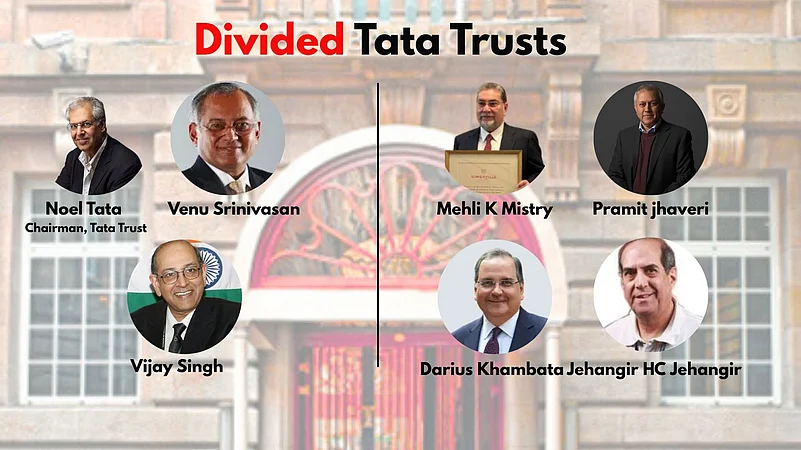

The proposal, supported by Noel Tata and Venu Srinivasan, was voted down 4–2, leading to Singh’s resignation soon after.

The episode has reignited questions over who truly holds power in the Tata empire, echoing the 2016 boardroom battle that ousted Cyrus Mistry.

Trustees of the Tata Trusts, the powerful governing body that majority owns Tata Sons, will meet today. The main agenda on the table is resolution of a brewing dispute that erupted at their last meeting at Bombay House — and it feels eerily familiar. Almost a decade after Cyrus Mistry’s ouster, and four years after the Supreme Court’s final verdict, the question of who truly controls the Tata empire has returned, only this time, the battle lies within the Trusts themselves.

On September 11, six trustees of the Tata Trusts, the umbrella body that controls a 66% stake in Tata Sons, met at Bombay House to discuss the reappointment of Vijay Singh, their long-time nominee on the Tata Sons board. Singh, 77, recused himself from the meeting as his reappointment was on the agenda.

The proposal, backed by Tata Trusts’ chairman Noel Tata and vice-chairman Venu Srinivasan, was voted down 4–2 by the other trustees. Days later, Singh, a former defence secretary of India and trustee of Tata Trusts since 2018, resigned from the Tata Sons board.

It was seen as a significant rebellion: one that reopened questions the Tata group thought it had settled nearly a decade ago. The core issue, once again, is who really holds power inside the Tata empire. In 2016, that same question had triggered one of India’s most dramatic boardroom battles when Cyrus Mistry was ousted as chairman of Tata Sons.

“Can a public trustee be subject to insider trading norms? Can minority shareholders sue them in a class-action suit for violations,” asked Anil Singhvi, founder-director of proxy advisory firm Institutional Investor Advisory Services, in Outlook Business’ December 2016 issue, summarising the tension between public accountability and private control. how

The Mistry affair

The ouster of Mistry led to a five-year legal battle between Mistry’s family-owned Shapoorji Pallonji (SP) Group, which holds 18% in Tata Sons, and the Tata Trusts, which owns the controlling stake through a network of charitable entities.

Mistry’s supporters raised “governance concerns” stemming from alleged “abuse of the Articles of Association (AoA)", which is the company’s internal constitution and defines the balance of power with its majority shareholders. In 2021, the Supreme Court dismissed these allegations and upheld the company's AoA, especially the rights of nominee directors Tata Trusts appoints on Tata Sons' board.

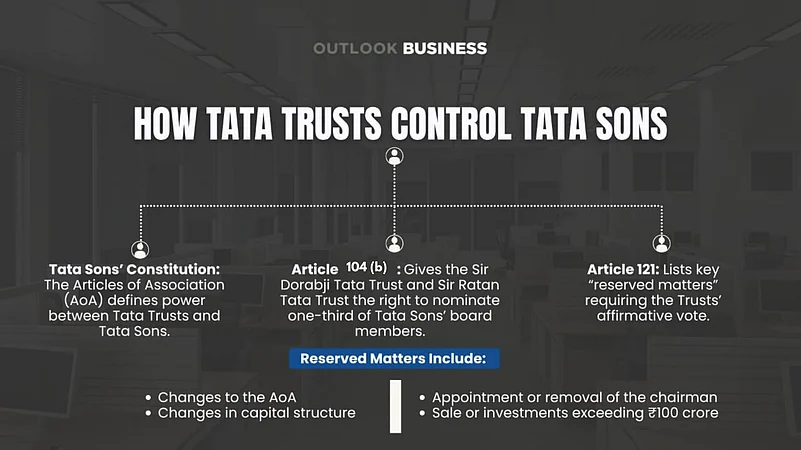

Two provisions—Article 104B(b) and Article 121—of Tata Sons' AoA have long been the focus of contention, according to Pune-based corporate lawyer Rishabh Gandhi, who is also the founder of Rishabh Gandhi and Advocates.

He explained that Article 104(b) gives the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust and the Sir Ratan Tata Trust (two prominent parts of Tata Trusts) the right to nominate one-third of Tata Sons’ directors whenever the board is constituted or a vacancy arises.

Meanwhile, Article 121 lists “reserved matters”, such as amendments to the AoA, appointment or removal of the chairman, sale of substantial assets, or investments exceeding ₹100 crore, which require the affirmative vote of the Trusts’ nominee directors.

"In practice, these provisions give the Trusts a decisive say in all major strategic decisions," said Gandhi. The minority shareholders, particularly the SP Group, have argued that these provisions distort the balance of power by entrenching the Trusts’ control and limiting the influence of other shareholders.

Nearly a decade later, the 156-year-old group once again finds itself in the midst of a dispute with Tata Sons’ AoA once again at the centre of contention. This time, the nominee directors are accused of not passing on complete information from the Tata Sons board to Tata Trusts.

While the opaque transfer of information had been reported, it escalated in a meeting of Tata trustees on September 11.

Vijay Singh is one of the seven trustees of Tata Trusts. Of the six trustees present at the meeting, Tata Trusts’ chairman Noel Tata and long-time trustee Venu Srinivasan forwarded Singh's renomination proposal. However, it was struck down by four trustees: Mehli Mistry, Pramit Jhaveri, Jehangir HC Jehangir and Darius Khambata. They tried to nominate Mistry, a long-time Ratan Tata confidant, for the role. However, Tata and Srinivasan opposed it and the meeting concluded without a decision.

Later, Singh stepped down from his post on Tata Sons' board. The next meeting of Trustees is scheduled on Friday, October 10.

Tata Sons' Contested Rulebook

The Tata group's origin can be traced back to 1868, when Jamsetji Tata founded his first trading firm. However, its holding company, Tata Sons, was incorporated as a private limited company under the Companies Act, 1913 in November 1917. Two years later, Tata Trust was set up to keep family control on the company.

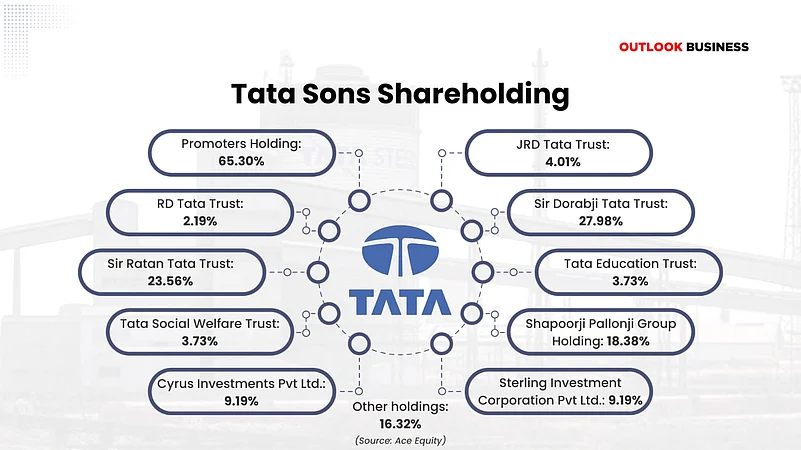

In 1965, Cyrus Investments and Sterling Investment Corporation, part of the SP Group, acquired shares in Tata Sons. Over the years, their shareholding in Tata Sons has grown to 18.37% of the company’s total paid-up share capital.

As per ACE Equity, a financial database, the Tata Trusts collectively hold a 65.30% stake in Tata Sons, distributed among the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust (27.98%), Sir Ratan Tata Trust (23.56%), JRD Tata Trust (4.01%), RD Tata Trust (2.19%), Tata Education Trust (3.73%) and Tata Social Welfare Trust (3.73%).

The remaining shares are held by various operating companies.

So, while Tata Sons is controlled by these charitable foundations, the group’s governance is shaped by the internal rulebook—AoA.

Over the decades, the company’s AoA underwent several amendments. Some of the key provisions included Article 75 that empowers the company to transfer ordinary shares by special resolution without notice; Article 86 that mandates that no quorum shall be formed at a general meeting unless a representative jointly nominated by the Tata Trusts, holding at least 40% of the paid-up capital, is present; Article 104, entitling the trustees of the Tata Trusts to nominate three directors; Article 118, which requires a selection committee to recommend the executive chairman as long as the Trusts hold at least 40% equity.

The last and most crucial amendment, Article 121 that mandated that all board decisions require the affirmative consent of the majority of Trust-nominated directors, was introduced in 2014, two years after the appointment of Cyrus Mistry as the chairman of Tata Sons.

At the time, when Ratan Tata was still the emeritus chairman and chair of Tata Trusts, Articles 121A and 121B were introduced to ensure that such decisions are mandatorily brought before the Board, where Trust-nominated directors are always the majority.

Those provisions later became central to the conflict between the Trusts and the then chairman Cyrus Mistry.

The 2016 Showdown

In October 2016, just four months before his term was supposed to end, Mistry was removed as chairman of the group. Officially, the company cited deteriorating performance of group companies, not fulfilling pre-appointment goals, and his “desire to seek control of group operating companies of the Tata group, to the exclusion of Tata Sons and other Tata representatives".

Mistry and SP Group accused Ratan Tata and the Trusts of “oppression and mismanagement” and took the fight to the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT).

In July 2018, the NCLT ruled in favour of Tata Sons, stating that Mistry’s removal as executive chairman was due to loss of trust. It held that his removal as director was prompted by the alleged leakage of confidential company information. Tata Sons had told the tribunal that Mistry had shared some of the company financial documents with the income-tax department.

The tribunal also concluded that proportional board representation was not mandatory and Articles 75, 104B, 118 and 121 were not inherently oppressive.

But a year later, in a subsequent appeal, NCLAT overturned the decision in favour of Mistry terming his removal "illegal” and reinstating him for the remainder of his tenure. It also restrained Tata Trusts’ nominee directors and Ratan Tata from making future decisions invoking Article 75.

Tata Sons challenged this verdict before the Supreme Court, which stayed the NCLAT order on January 10, 2020. Finally, in March 2021, the Supreme Court delivered its judgement in a joint hearing of all 15 appeals, ruling in favour of the Tata group.

The Supreme Court observed that the role of executive chairman has no statutory recognition, and even removal from directorship cannot be deemed oppressive or prejudicial. It rejected claims of oppression and mismanagement, stating that Mistry’s own actions warranted his removal.

That ruling, meant to settle the debate over governance, has instead re-emerged in 2025 with the question: Who within the Trusts gets to exercise those powers now that Ratan Tata is gone?

Return of the old debate

The Supreme Court’s 2021 verdict closed the Mistry chapter, but it didn’t fully resolve the question of how much power the Tata Trusts should hold over Tata Sons.

“The 2021 order favoured Tata Sons on the Mistry claims,” said Shravanth Shanker, advocate-on-record, Supreme Court. “But it did not create an absolute, judicially granted power for the Trusts."

He added that Tata Sons’ AoA is at the root of the recent shareholder dispute because they stipulate how board seats are filled and what powers key stakeholders, particularly the Tata Trusts, hold over pivotal decisions at the company. "Ergo, the current dispute is effectively a dispute over who gets to exercise those rights," he added.

The AoA gives Tata Trusts substantial level of control over the conglomerate, which has a net worth of ₹1,49,680 crore.

Tata Trusts have veto rights on key Tata Sons’ decisions, restricting minority shareholders like SP Group, according to Rajarshi Chakrabarti, senior partner at corporate law firm Kochhar & Co.

"The articles require Tata Trusts approval for transferring or using Tata Sons shares as collateral, restricting SP Group’s ability to leverage their stake. This dual control curbs both their governance influence and financial flexibility. This has been a contentious issue for a while but has assumed significance in the context of the listing controversy coupled with SP Group’s financial position," he added.

The decision also reaffirmed that all directors continue to owe fiduciary and statutory duties under company law, according to Nilesh Tribhuvann, managing partner, White & Brief–Advocates and Solicitors.

Rishabh Gandhi also agreed that the ruling held that even nominee directors must comply with fiduciary obligations under Section 166 of the Companies Act, 2013, which require them to act in good faith and in the best interests of the company rather than their nominator.

"The judgement made it clear that these rights cannot be exercised arbitrarily and that minority shareholders continue to enjoy remedies against oppression or mismanagement under Sections 241 and 242 of the Act," he said.

Adding that this balance between control and accountability has now become the focal point of the 2025 dispute. Dissenting trustees have accused their colleagues of limiting transparency and restricting information flow, allegedly in breach of the principles laid down by the court.

While the initial arguments suggested that the trustees’ opposition might be an attempt to improperly take control of Tata’s boardroom and thereby its key decisions, people close to Mehli Mistry have come out to deny this narrative. Amid this counter narrative, all eyes will now be on what happens in the trustees’ meeting on today.