Tata Trusts’ meeting on Friday sidestepped key questions facing the Tata Group.

These include Tata Sons’ plans to remain private despite the RBI’s mandate for a public listing.

The holding company of India’s largest conglomerate has applied to surrender its NBFC licence to avoid the mandate.

But its minority shareholder, the SP Group, continues to call for an initial public offering.

The closely watched Tata Trusts meeting on Friday avoided two critical issues facing India’s largest conglomerate Tata Sons. They set aside the matter of Tata Sons board appointment which had divided the seven trustees in the last meeting in September. They also didn’t discuss how they plan to keep Tata Sons private in the face of the RBI’s public listing mandate.

The Tata Trusts board meeting largely focused on routine matters such as funding proposals and charitable initiatives, according to reports. This followed government intervention urging stability within the group. Observers described the meeting as “cordial” and “constructive.”

In the first part of this story 'the Tata Power Struggle: Old Ghosts, New Fault Lines', Outlook Business explained in detail the dispute over who controls Tata Sons. In Part 2, we look at what that control means and why it matters whether the company stays private.

In 2022, the RBI classified Tata Sons as an “upper-layer” core investment company, or a non-banking financial company. The move effectively treated Tata Sons as a large financial holding company, requiring it to meet stricter disclosure and governance standards, including a mandatory public listing by September 30, 2025. That deadline has now lapsed.

Tata Sons, however, maintains that it is not primarily engaged in financial business but functions as an industrial holding company. In March 2024, it applied to surrender its registration as a core investment company, a request that remains pending before the RBI. The central bank has clarified that such entities may continue operations while their applications are under review.

As part of the surrender of its licence, Tata Sons also promised to remain debt free. According to rating agency Icra’s note, Tata Sons’ net debt came down from ₹20,642 crore in March 2023 to a cash-positive ₹2,680 crore as of March 31, 2024.

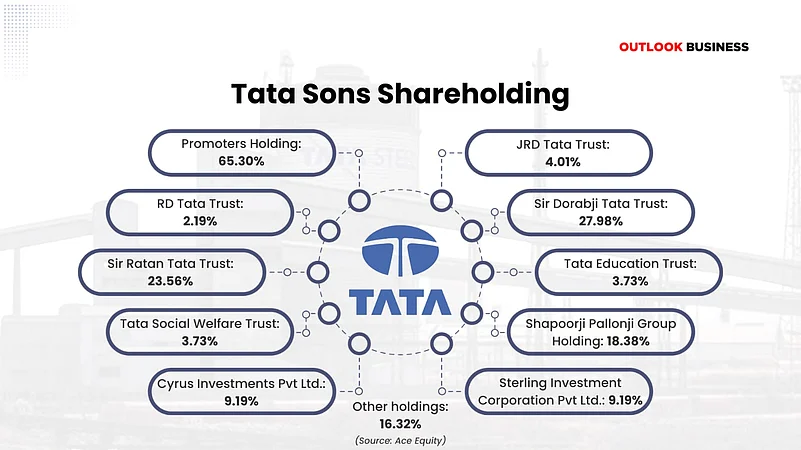

But the RBI is not the only stakeholder here. Its minority shareholder, the Shapoorji Pallonji (SP) Group, has written to the central bank demanding that Tata Sons should be listed.

The demand, while having a background in the power struggle of 2016, also stems from the SP Group's financial stress. The group remains heavily in debt, which some estimates claim is about ₹60,000 crore. Much of this debt is backed by its 18% stake in Tata Sons and part of it was recently refinanced through a private credit facility, which is costlier than a corporate loan.

For now, both parties remain in talks to provide the SP Group liquidity, which may include a complete exit from Tata Sons. The Tata group has reportedly proposed buying back a 4–5% stake, which may provide the SP Group ₹29,000 crore.

The buy-back proposal was also discussed in a recent meeting between Tata Sons’ chairman N Chandrasekaran, Tata Trusts chair Noel Tata and two trustees with Union Home Minister Amit Shah and Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman. In the meeting, the executives were suppose to urge the government to provide some regulatory relief in buying back stocks, which may incur massive capital-gains tax, and Tata Sons might have to raise external debt. We don’t know if such requests were raised.

What we do know is that the ministers asked the Tata executives to do "whatever it takes" to resolve the dispute among the trustees.

On October 10, the Shapoorji Pallonji (SP) Group reiterated its demand for the public listing of Tata Sons.

“In light of the recent developments pertaining to the internal matters of Tata Trusts, it is both timely and necessary to reiterate our long-standing position — one that has always been rooted in transparency, fairness, public interest, and adherence to the principles of good corporate governance,” the group said.

Why Tata Sons Wants to Remain Private

Legal experts say Tata Sons’ push to avoid listing is more about preserving its promoters’ original goals.

"If Tata Sons goes public and lists its shares, its articles of association [AoA] will require major clean up, negating the current affirmative rights of the Tata Trusts, including their veto powers," said Rajarshi Chakrabarti, senior partner at law firm Kochhar & Co. He added that this would subject Tata Sons to Sebi regulations, under which minority shareholders like the SP Group would gain voting rights on key decisions.

In short, a public listing could dilute the trusts’ control over Tata Sons, the holding company of the Tata group–a matter which is the core of the current battle.

"Such changes could constrain Tata Trusts’ control and create barriers to their unchecked dominance over Tata Sons. Consequently, the listing could materially alter the governance dynamics of the company," he added.

But for the authorities, the risks are broader. The rules under which Tata Sons has been asked to list were brought in following the IL&FS and DHFL crises. IL&FS, a key infrastructure financing firm, defaulted on its debt of over ₹90,000 crore in 2018, triggering a liquidity crisis across non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and mutual funds. At the time the company was still not listed on the public market.

A year later, DHFL (now rebranded as Piramal Capital & Housing Finance), a major housing finance company, collapsed under the weight of bad loans and allegations of diverting ₹31,000 crore through shell firms.

These major shocks to India’s financial system exposed deep cracks in the country’s shadow banking sector. It also pushed the RBI and the Ministry of Corporate Affairs to tighten oversight of large private conglomerates for more financial transparency and better governance.

"Trend suggests that while Tata Sons may continue to operate as an unlisted entity in the short term, long-term regulatory pressure for greater public accountability will only increase," said Rishabh Gandhi, founder, Rishabh Gandhi and Advocates.

In 2021, when the Supreme Court sided with Tata Sons in the case examining the removal of Cyrus Mistry as its chairman, it also gave its blessing to the group's current structure. It upheld the current governance system under which Tata Sons' majority decisions must go through three nominee directors appointed by its majority owner, Tata Trusts.

Under Tata Sons’ AoA, these directors have the rights to take a call on all investments or sales exceeding ₹100 crore and to appoint the chairman and board members.

According to Tushar Kumar, a Supreme Court lawyer, while originally intended to preserve the group’s philanthropic ethos and ensure continuity of vision, these provisions have, over time, become the very fault line of contestation, pitting trustees against one another and raising larger questions about accountability, transparency, and control in one of India’s most storied conglomerates.

"The AoA, therefore, sits at the epicentre of a delicate balance between trusteeship and corporate governance, and any discord therein inevitably reverberates through the broader Tata ecosystem," he added.

According to Nilesh Tribhuvann, managing partner, White & Brief–Advocates and Solicitors, there can be governance concerns when public charitable trusts exert significant influence over listed entities.

"These include potential misalignment between charitable objectives and commercial goals, lack of transparency in trust operations and perceived shadow control through nominee directors, which may raise questions about minority protection and board independence," he said, adding that when structured carefully and operated with transparency, this model can encourage long-term thinking, ethical conduct and responsible management.

The key lies in maintaining clear boundaries, ensuring full disclosure, and fostering a governance culture that respects both fiduciary duties and the overarching mission of public good.

Ketan Mukhija, senior partner, Burgeon Law, points out that similar trust-based structures, such as the Azim Premji Trust’s holdings in Wipro, show how philanthropic entities can shape corporate direction.

"This blend of charitable purpose and corporate control calls for stronger governance clarity in India," said Mukhija.

Public Listing Amid Growth Concerns

The demand for Tata Sons' listing comes at a time when the company has been facing volatility in its earnings. Data from corporate-data provider ACE Equity shows that Tata Sons’ growth in profitability has been more uneven over the past 10 years. The company’s profit after tax (PAT) has shown significant fluctuations, rising to ₹49,000.66 crore in FY24 from ₹23,121.74 crore in FY16.

Further, in FY25, PAT stood at ₹40,985.19 crore, sharply down from ₹49,000.66 crore in the previous year, due to increased expenses from ₹4,17,083.58 crore to ₹5,37,618.27 crore. Last year, Tata Sons' consolidated total income stood at ₹5,92,673.56 crore.

Public listing comes with the pressure to show growth every three months to keep shares attractive for investors, and right now, many of Tata group’s companies are in a phase of capital-intensive growth. It remains to be seen if Tata Sons succeeds in its efforts.