A patriarch holds the family firm not because everyone agrees with him but because his shadow is too vast to contest. Empires often crumble within years of the passing of the one figure who kept personal ambitions in check.

The 156-year-old Tata group finds itself in a similar situation. Its patriarch, Ratan Tata, passed away last year, and now the group is alive with ambitions and rivalries that, some say, could tear the $326bn conglomerate asunder.

Trouble Brewing

The first sign came on September 11 this year. Inside the boardroom of Tata Trusts, the powerful body that controls over 65% of Tata Sons, a vote on the reappointment of former defence secretary Vijay Singh split the seven-member board. Singh, 77, recused himself while the others voted. When the count ended, four were against and two in favour.

It could have ended there, but it did not. Soon after, Singh resigned from the board of Tata Sons, and the long-frozen lines of loyalty within the Tata establishment began to shift once more.

When Ratan Tata presided over the group’s affairs, dissent was rare, at least in public. Even after he stepped down as chairman of Tata Sons in 2012, his word remained final on most matters concerning the group’s long-term goals. Cyrus Mistry, his successor, lost his position, among other things, for attempting to halt projects such as the Tata Nano and Corus, the loss-making European arm of Tata Steel.

“While Tata is India’s most valuable brand and conglomerate, it is also now a part of a much more liberalised economy and active financial market. These broad macro forces inevitably create conditions where there would be a tussle for control,” says Prateek Raj, associate professor of business management and health sciences, University College London.

In Search of Balance

For decades, the Tata group moved under the quiet authority of Ratan Tata. Decisions were swift, ambitions checked and minority shareholder, the Shapoorji Pallonji (SP) Group, watched from the margins.

After his passing, the successors sought to ensure that no single personality would again wield such power. They introduced a resolution requiring annual voting to reappoint any director over the age of 75—a quiet safeguard against the concentration of authority.

The first to invoke this clause was Mehli Mistry, cousin of Cyrus Mistry and connected by blood to the SP Group, which holds 18% of Tata Sons, who used the rule to challenge Noel Tata, the current chairman of the Trusts and half-brother of the late Ratan Tata.

Mistry has on his side several members of the Trusts, including Pramit Jhaveri, Jehangir HC Jehangir and Darius Khambata. Despite not being from the Tata family, they see a chance to assert themselves within a timeframe that may be short but decisive in the group’s history.

“Ratan Tata’s dual chairmanship of Tata Sons and the Tata Trusts concentrated influence in a way few corporate structures allow. His passing has revived dormant questions of succession and control,” says Ketan Mukhija, senior partner at Burgeon Law.

Trustees backing Mehli Mistry have voiced concerns over lack of transparency from those representing the Trusts on Tata Sons board. Vijay Singh’s ouster, it appears, was plotted because of his proximity to Noel Tata and Venu Srinivasan, both nominees of the Trusts on the Tata Sons board. The rival camp, led by Mehli Mistry, sought entry into the small circle that decides the fate and stature of everyone.

Amid this internal conflict, Tata Trusts unanimously re-appointed Srinivasan as a trustee for life, just days before the expiry of his tenure. Mehli Mistry, whose term is also due to expire in October, is also expected to be reappointed.

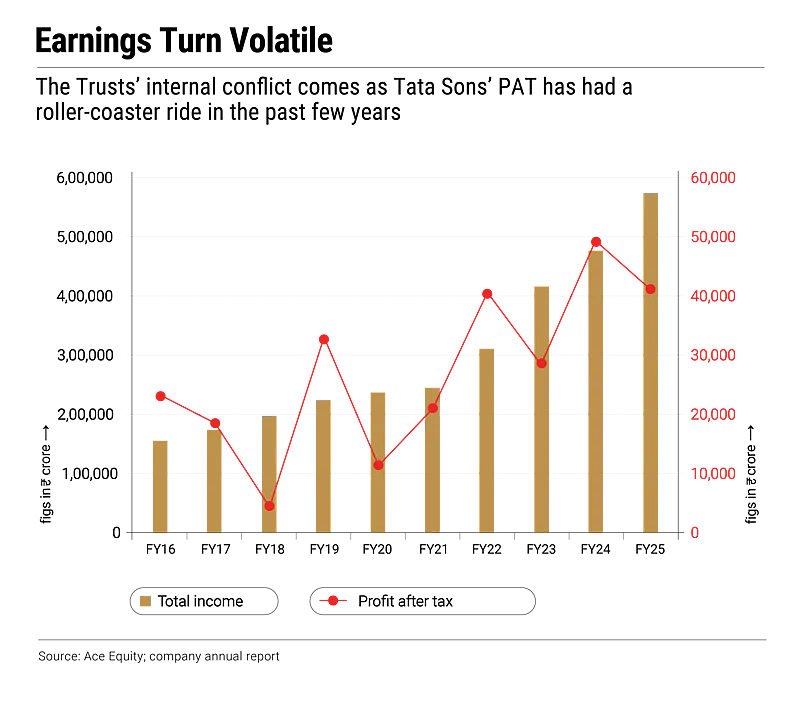

Mehli Mistry has reportedly given a conditional approval for the reappointment of Srinivasan, demanding that for all future trustee renewals approvals should be unanimous. If any future resolution for reappointment was not unanimous, his approval would be withdrawn. The tension inside the Trusts comes just as Tata Sons earnings have turned volatile. Data from ACE Equity, a database of Indian companies, shows that its profit growth has been uneven over the past decade, rising from ₹23,121 crore in 2015–16 to ₹49,000 crore in 2023–24, before dropping to ₹40,985 crore in 2024–25 as expenses climbed sharply from ₹4,17,083 crore to ₹5,37,618 crore between 2023–24 and 2024–25.

Tata Rule Book

The group faces mounting pressure to deliver at a time when global trade remains unsettled and its crown jewel, Tata Consultancy Services, has been under strain for a few quarters.

SP Group, now seeks a greater voice in shaping the Tata group’s future. Yet, two clauses in Tata Sons’ Articles of Association (AoA) tilt the scales in favour of Tata Trusts. Article 104(b) allows the Trusts to nominate one-third of Tata Sons’ directors, giving them sweeping influence over strategic decisions. Article 121 requires their consent for any investment exceeding ₹100 crore, any change in leadership or any major shift in direction.

It was these very provisions that Cyrus Mistry challenged in court after Ratan Tata unseated him from the chairmanship of Tata Sons in 2016.

A public listing would expose Tata Sons to Sebi’s disclosure and governance requirements, shareholder activism and market volatility, potentially weakening the Trusts’ influence and diverting dividends that fund their charitable missions

“The AoA sits at the centre of a delicate balance between trusteeship and corporate governance,” says Tushar Kumar, a Supreme Court advocate. “While originally intended to preserve the group’s philanthropic ethos and ensure continuity of vision, these provisions have, over time, become the very fault line of contestation, pitting trustees against one another and raising larger questions about accountability, transparency and control.”

The 2021 Supreme Court ruling upheld the Trusts’ special rights but did not grant them absolute power. “The Court made it clear that the Trusts’ rights remain subject to company law and cannot override statutory duties or enable oppression,” Rajarshi Chakrabarti, senior partner at law firm Kochhar & Co, had earlier told Outlook Business.

Governance Squeeze

In 2022, the RBI classified Tata Sons as an ‘upper-layer’ Core Investment Company (CIC) under its scale-based framework for non-banking financial companies. The designation meant tighter oversight, mandatory disclosure and a compulsory public listing by September 30, 2025. For years, Ratan Tata’s towering stature had earned the group quiet indulgence from regulators.

Tata Sons has since argued that it is an industrial holding company, not a financial one, and in March 2024 sought to surrender its CIC registration after clearing its debt. The RBI has yet to decide. But in a moment when trustees are divided, the regulator will find it difficult to grant special dispensation.

“If the RBI mandates a listing, it will change the character of the company…the Trusts’ veto powers will have to go, and their shareholding will likely be diluted,” says Shriram Subramanian, managing director, InGovern Research Services.

A public listing would expose Tata Sons to Sebi’s disclosure and governance requirements, shareholder activism and market volatility, potentially weakening the Trusts’ influence and diverting dividends that fund their charitable missions.

While the Tata model now faces pressure to evolve, other legacy groups have adjusted more easily to modern governance demands, though none resemble Tata’s trust-controlled architecture.

“Tata Trusts’ situation is relatively sui generis,” observes Alay Razvi, managing partner, Accord Juris, a law firm. “In contrast, other legacy entities such as the Godrej Family Foundations, the Azim Premji Trust and Foundation and the Birla group’s promoter and charitable bodies have faced calls for greater clarity and governance, but not a regulatory push to list their apex holding companies.”

There can be governance concerns when public charitable trusts exert significant influence over listed entities. “These include potential misalignment between charitable objectives and commercial goals, lack of transparency in trust operations and perceived shadow control through nominee directors,” says Nilesh Tribhuvann, managing partner, White & Brief–Advocates and Solicitors.

The Road Ahead

Without a figure like Ratan Tata to command quiet consensus, the Trusts now stand at a crossroads. The longer the infighting festers, the stronger the argument grows for throwing open the doors of Tata Sons to public scrutiny. The group’s might was never just in its balance sheet but in the moral gravitas of the man who led it. With that gone, the opacity that once signified discretion now begins to look like evasion.

Experts say Tata Sons faces three choices. It could buy back the SP Group’s stake, preserving control but risking debt and regulatory glare. It could list on the exchanges, inviting accountability it has long kept at bay. Or it could seek a waiver, setting a precedent that might one day return to haunt Indian capitalism itself.

The Indian state, too, will be tested. These are uneasy times for a nation that needs its corporate champions to keep faith in the growth story. With the US, China and others backing their industrial titans, India can ill afford to watch its most trusted conglomerate unravel. Without Tata, who would have taken Air India when it bled?

Raj, the academic, says, “Tata remains India’s crown jewel...because it aspires to balance financial power with a philanthropic soul.” That balance now trembles on a knife’s edge. The house that once defined trust must now earn it in public view. Perhaps this is the irony of legacy; the ideals that once shielded the empire now demand its exposure. Without Ratan Tata’s shadow, the group must learn to walk in the light.