Amidst the changing tides of global trade patterns and geo-spatial boundaries triggered by a wave of international events, including an increasingly erratic US President, emerging economies have a lot to balance against in reimaging their trade policies and while securing preferential trade deals, anchored as FTAs (Free Trade Agreements) with dominant trade partners.

In the India-US context, for all the diplomatic warmth and strategic alignment defining the current form and dynamics of bilateral ties, embedded in areas from defence pacts to semiconductor cooperation, one pillar remains unresolved: Trade.

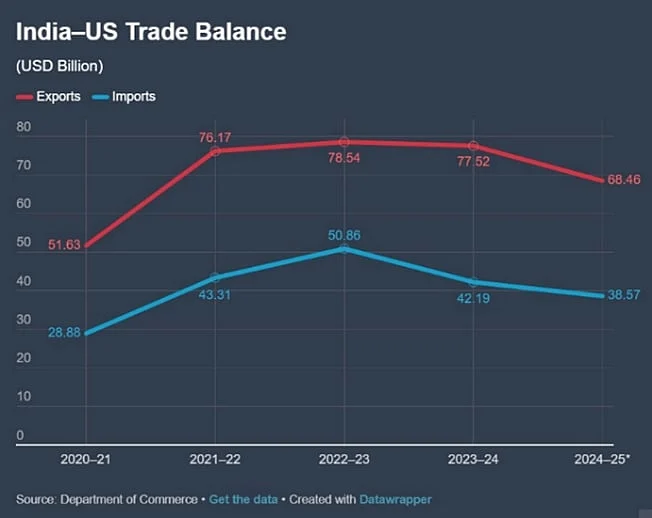

Bilateral goods and services trade between the two countries soared to $131.84bn in financial year 2024–25, with India exporting pharmaceuticals, software services and gems while importing aircraft engines, oil and defence systems. Yet, beneath this pleasant arithmetic lies a complex reality of uneven benefits and cautious-mistrust. This was also before Trump-ism wreaked havoc with its reciprocal tariff measures. More importantly, India’s $41.18bn goods trade surplus tells only half the story. As the Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI) study highlights, when services, intellectual property royalties and arms exports are factored in, the US holds a $35-40bn surplus, fuelled by India’s growing appetite for American technology, weapons platforms, cloud services and the export of Indian talent to US firms.

Despite this, trade negotiations often pressure India to open its markets wider, faster and with fewer safeguards. This needs a cautious review particularly in areas like agriculture, dairy, food processing etc where Indian markets and its workers are more vulnerable.

In this backdrop, the US is experiencing under Trumpism a confused economic and trade policy that baffles critical reasoning and sound economic logic/principles.

The US federal court’s ruling on May 28, 2025, declaring Trump-era tariffs on steel, aluminium and other goods unlawful comes with an already critical window of 90-days. These tariffs imposed under the guise of “national security,” has epitomised a confrontational approach to trade, which is dangerous particularly for carefully vetted and reasoned negotiations.

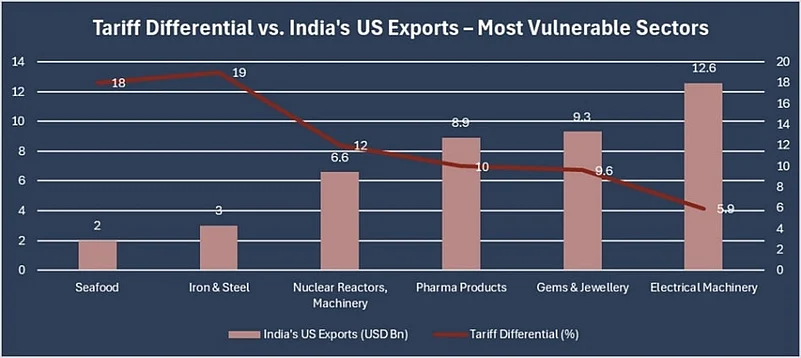

With respect to India, the US’ own position under Trump hasn’t looked very promising. As a senior official told Reuters, the recent tariff pause offers immediate relief to exporters in seafood and light manufacturing where $12bn in exports face potential 8-12% margin erosion. More crucially, it provides time to craft a limited but sound trade pact, targeted for completion by autumn 2025, with ambitions to propel bilateral trade to $500bn by decade’s end.

The pause however shouldn’t be misunderstood as goodwill. The United States under Trump has attacked sparing allies like India, while targeting China, signalling a new phase of trade hostilities, while also positioning India as a pivotal player in a reconfigured global supply chain.

Yet, daunting choices loom for the Indian scenario. Should India liberalise agriculture, risking the livelihoods of 700mn tied to smallholder farming? Can micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), driving significant export value, withstand low-cost imports if tariffs are slashed? Should New Delhi concede on digital trade, potentially compromising data sovereignty?

GTRI urges India to resist concessions tied to unlawful tariff threats, advocating a deal rooted in reciprocity, resilience and realism. This is India’s moment to strategically navigate the global trade landscape, leveraging its unique strengths to secure a transformative agreement.

India is therefore now poised to capitalise on its competitive edge in services, digital technology and pharmaceuticals.

Leveraging India’s Comparative Advantages

India’s evolving trade posture with the United States must be guided by a twin imperative: maximising strategic gains in areas of proven global competitiveness while reinforcing vulnerable sectors from premature exposure. In financial year 2024-25 India’s merchandise exports to the US totalled $89.81bn which is just 18% of its overall exports (approximately $437bn) according to the Ministry of Commerce. Unlike Vietnam (87%) or Thailand (65%), which are far more reliant on the US market, India’s relatively low dependency offers it rare negotiating bandwidth.

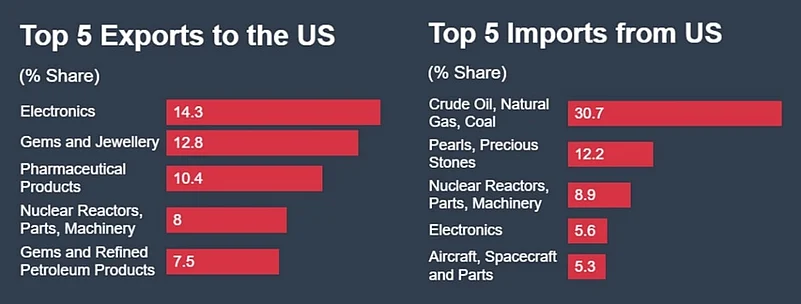

India’s strengths are clearest in IT services and pharmaceuticals, where consistent American demand has created durable trade surpluses. Gems, textiles and telecom follow closely, sectors ripe for deeper market access.

A ScienceDirect study on US-India services trade reveals that India’s computer and information services alone accounted for more than two-thirds of its commercial services exports, driven largely by sustained American demand for cost-effective, skilled labour. In 2024, India’s IT services exports to the US alone reached an estimated $50bn. Pharmaceuticals, aided by India’s status as the “pharmacy of the world”, added another $12.7 bn, much of it entering the US tariff-free under existing provisions.

To build on these comparative advantages, India must pursue preferential market access for its leading sectors. For example, textiles ($9.6bn in exports) and gems and jewellery ($9bn) stand to gain from tariff differentials: while China hits back with 34% tariffs on all U.S. goods, Indian exports typically encounter lower barriers at 26%. Policy think tanks like Niti Aayog recommend targeting such asymmetries in a potential Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA), while simultaneously diversifying trade ties to markets like the EU (European Union)and Asean (Association of Southeast Asian Nations). Notably, textile exports to these regions grew by 6.32% in financial year 25. Since the signing of Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA) , bilateral merchandise trade has more than doubled, rising to $26bn in financial year 23 from $12.2bn in financial year 21 provides a working template.

Yet, the risks of a broad low-tariff arrangement remain stark. Agriculture, food processing and MSMEs, each foundational to India's employment and livelihood base could suffer disproportionate damage. Agriculture alone supports over 700mn people and contributes 15% to GDP(Gross Domestic Product). It also enjoys weighted tariff applied tariffs of 37.7%, compared to the US’s 5.3%.

A sudden opening of India’s agricultural sector would invite heavily subsidised US farm products, where subsidies often cover huge amount of production costs, to flood Indian markets, potentially displacing smallholder farmers. Meanwhile, The fresh tariffs from the US, particularly the 26% tax on Indian exports, are a big setback for Indian MSMEs which contribute nearly 45% of its total exports

Following the court ruling that paused some of the Trump-era tariffs, India finds itself with a fleeting window of relief which shouldn’t be looked upon as a solution, it only underscores the urgency for built-in protective clauses. Options include tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) to cap agricultural inflows, phased tariff reductions for MSMEs and sensitive product carve-outs for key goods like dairy and pulses. India can take cues from its ongoing UK-India FTA, which phases tariff reductions over seven years, this is a pragmatic model that tempers liberalisation with domestic security.

Strategic Framework for a Balanced Deal

For India, any future engagement on a Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) with the United States must be guided by strategic sequencing and sectoral differentiation. One way forward is to design a phased trade deal that deliberately excludes hyper-sensitive sectors such as dairy, certain pulses and low-margin MSME products from immediate liberalisation.

A “forward most-favoured-nation” (MFN) clause could be incorporated to ensure India enjoys automatic benefits if the US extends better terms to other trading partners later. This would preserve negotiating leverage in an evolving trade landscape.

There are valuable precedents to draw from. The US-Japan trade agreement (2019) concessions in agriculture and digital trade but created regulatory coherence in automotive and technology standards, securing both access and autonomy. Similarly, the recently announced UK-India FTA offers lessons in how to sequence tariff phase-outs while embedding safeguard clauses and labour protections.

Looking ahead, the two democracies have the potential to scale bilateral trade to $500bn over the next decade, if supported by the right institutional scaffolding. India’s young workforce, digital scale and improving infrastructure give it long-term structural advantages especially in services, clean tech and high-skill manufacturing. But these must not come at the cost of domestic dislocation or economic precarity for small producers.

As India prepares for deeper integration into global value chains it must also remember that trade is not a race to liberalise but a strategy to modernise.

As a trade economist recently said, “The real success of a trade deal lies not in the number of tariff lines reduced, but in the number of lives it uplifts without leaving others behind.” India’s trade diplomacy too, with the United States and other dominant trade anchors, must strive for exactly that kind of success - measured, equitable and anchored in developing a long-term economic bond which is resilient, while safeguarding our own industrial centres and workers.