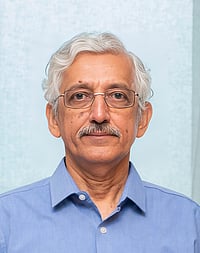

Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, director general of meteorology at the India Meteorological Department (IMD), popularly known as the "Cyclone Man of India" due to his accurate predictions of cyclones, recently won the United Nations Sasakawa Award for Disaster Risk Reduction 2025. He has also been conferred the Outstanding Service Award 2025 from the American Meteorological Society for enhancing tropical cyclone prediction and warning systems in the Indian Ocean region.

With over 30 years of experience in the field of meteorology, Mohapatra serves as the third vice president of the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO).

In an exclusive interview with Outlook Business, Mohapatra discusses the impact of climate change on weather forecasting, the evolution of forecasting over the years, gaps in current weather forecasting and the IMD’s research and development in artificial intelligence.

Due to climate change, extreme weather events like heatwaves and cyclones are becoming more frequent and intense. How is IMD helping in predicting these?

Climate change is an ongoing phenomenon that has accelerated due to human activities. As the nodal agency, IMD assesses these shifts and shares the findings with the government, public and international bodies like the WMO and IPCC. Although predictability has declined, IMD has improved its forecast accuracy over the past decade by upgrading its observational systems to deliver denser, more frequent and standardised data. The rise in localised weather extremes has made this even more critical.

How has IMD improved community engagement and accessibility?

A month ago, associations of rickshaw-pullers, street vendors and domestic workers in Delhi asked for weather forecasts. We responded by providing updates, which they translated into local languages and displayed in markets. That kind of community engagement is central to what we’re building.

Today, our forecasts are hyperlocal. We’ve moved from national- and state-level forecasts to alerts at the block and even panchayat level. The Panchayat Mausam Seva, launched in January 2024, delivers information to ward members, sarpanches and panchayat secretaries. We also reach grassroots workers like Krishi and Pashu Sakhis.

We have also set up WhatsApp groups across one lakh villages. Our target is 10 lakh.

Moreover, we have started public weather observations. Citizens can report missed forecasts through our website or app. These reports help validate model accuracy and enhance nowcasting.

How do forecasts help farmers?

Since 2018, we’ve issued weekly extended-range forecasts valid for four weeks. These are especially useful for the first two weeks and help farmers plan crop sowing, fertiliser use and water management based on expected rainfall. If farmers know there’s above-normal rainfall ahead, they can start sowing early, plan inputs and anticipate better water storage.

We display these forecasts on boards at “hundis”—local procurement centres where farmers bring produce to sell. We also partner with private organisations like the Reliance Foundation and the MS Swaminathan Foundation to reach farmers.

Has forecasting helped in reducing loss of life?

Absolutely. Since 2019, we have implemented impact-based forecasting for cities and districts. For cyclones, we provide layered information—rainfall intensity, wind speed, storm surge levels and flood risk—to help determine evacuation needs, potential damage and the types of houses at risk.

We’ve also introduced lightning prediction models that offer alerts 12–24 hours in advance. These efforts have significantly reduced fatalities during extreme events like heatwaves, cyclones and heavy rainfall. That said, challenges remain, particularly in forecasting lightning and short-lived storms.

You've worked in IMD for a long time. How has forecasting evolved over the years?

When I joined IMD, we were manually plotting weather charts based on limited observations sent via telegram or teleprinter. It took three hours to collect the data and another three to plot it. Forecasts were based on hand-drawn charts and were valid for just 24 hours. Numerical models didn’t exist. Confidence in forecasts was low.

Over the past decade, advances in technology have transformed this landscape. We now operate over 2,000 automated weather stations, 6,400 rain monitoring stations and 45 modern radars—with a target of 126 under the Mission Mausam programme. Radars offer data at a resolution of 350 metres, compared to the 4 km resolution of satellites.

Our high-performance computing systems allow us to generate 10-day forecasts in under four hours. Forecast accuracy has improved by 40–50%. Since 2013, we’ve introduced nowcasting systems that offer three-hour forecasts for short-lived local events like thunderstorms and hailstorms.

What led to the delay in the monsoon's arrival in Delhi this year, and why did the IMD's predictions fall short?

The monsoon reached most of India but was delayed in Delhi, parts of Haryana, northern Rajasthan and southwest Uttar Pradesh due to a low-pressure system in Madhya Pradesh. This stalled the northward movement of the monsoon trough.

Forecasting becomes harder as the geography narrows. Small spatial zones pose higher challenges in accuracy. While we could confirm its advancement in broader regions like western Uttar Pradesh, pinpointing cities like Meerut or Delhi becomes much more complex.

How does IMD collaborate with research institutions?

We work with over 100 institutions, including IITs, IIITs and the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services. These partnerships span data-sharing, joint studies and training. Our scientists also guide PhD students and pursue their own doctoral research.

Since the formation of the Ministry of Earth Sciences in 2006, departmental collaboration has improved, leading to a better understanding of climate systems.

What are IMD’s current R&D priorities?

Artificial intelligence is a key focus. While we are still at a preliminary stage, we use AI to detect cyclone intensity and predict heatwaves at a small-scale. We also tap into global models, such as those from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

Over the next five years, we expect AI to become deeply integrated with our forecasting systems, working alongside physical models to improve accuracy and efficiency.

What role does IMD play for neighbouring countries?

IMD serves as a regional hub for weather services across 13 countries. We provide forecasts for cyclones, severe weather, rainfall, wind and wave conditions. Nine countries receive our daily alerts, particularly for the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea regions.

We also support capacity building by training personnel from neighbouring countries and providing long-range climate outlooks. As Vice President of the World Meteorological Organization, I work to ensure India contributes to global forecasting and disaster preparedness policy.

How are IMD personnel being trained to keep up with climate realities?

We follow WMO training protocols and conduct annual sessions at our recognised centres in Pune and Delhi. These courses are open to both Indian and international meteorologists. We also send our staff abroad for training. Our goal is continuous upskilling to match the pace of technological advancement.

How are businesses and start-ups involved in your work?

We currently support around eight start-ups that use IMD data to build new technologies. Earlier, we relied on imports for radars and instruments. Now, Indian firms manufacture them domestically through partnerships with IMD. Public-private partnership is critical to strengthening India’s weather infrastructure.

How is IMD addressing urban heat islands and heatwaves?

We are working on three fronts: expanding our observation networks, refining our scientific understanding of urban heat and building customised models for urban areas. Pilot projects are underway in Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata and now Delhi.

In Delhi, we now generate forecasts for 18 locations across seven districts. These are published in GIS format, allowing for neighbourhood-level mapping and planning. Our aim is to support urban adaptation to increasingly intense heat.

What is IMD’s long-term vision?

Our Vision 2047 outlines goals over five, ten and twenty years. By 2047, every Indian household should have real-time access to weather and climate information. Every village should have its own automated weather station. In the next five years, the goal is to install automated weather stations in every panchayat.

More importantly, we want citizens to become part of the ecosystem—as “citizen scientists” who report conditions.