Sanjay Agarwal built AU Bank from scratch, guided by disciplined risk management.

Cricket lessons shaped AU’s long-term strategy of patience and controlled growth.

AU crossed ₹1 lakh crore by diversifying products and keeping lending secured.

Transition to universal bank reflects focus on stability, scale and succession.

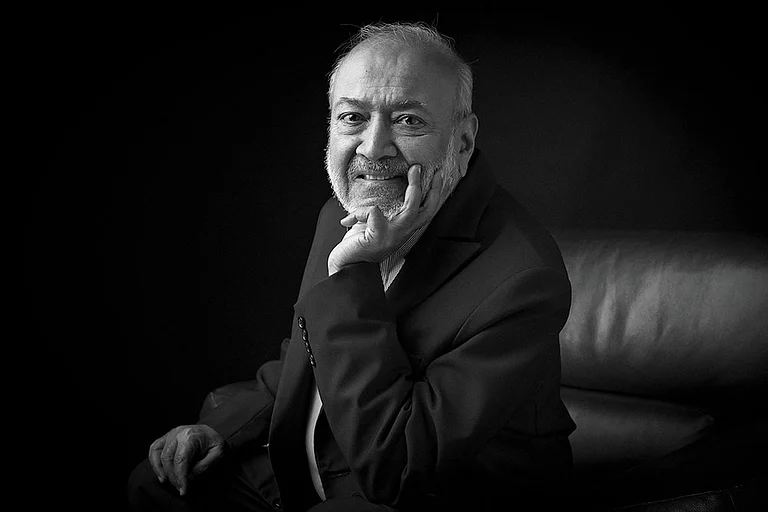

When the history of Indian banking is written, AU Small Finance Bank’s MD & CEO Sanjay Agarwal hopes to be remembered as a challenger, as someone who built something from nothing, rather than as a CEO of a bank. It reflects not just his pride, but also the stubborn grit that carried him from a middle-class upbringing in Jaipur to the corner office of one of India’s most remarkable home-grown banks. As AU Small Finance Bank gets ready to become the first small finance bank to transition into a universal bank, it mirrors the entrepreneur’s desire to inspire countless other middle class Indians to dream big.

With no family capital, no business legacy and no godfather in finance, Agarwal built his first lending business in 1996 on little more than borrowed trust, and a promise: Your money is safe with me. That trust and resolve would become the very foundation of the institution he would eventually create.

In this exclusive conversation with Outlook Business, the cricketer-turned-chartered accountant recalls learning early the importance of staying put, of surviving the initial overs, and that life rarely hands out advantages and one must build amid imperfections.

From vehicle finance to micro-business lending, from housing credit to eventually becoming a full-fledged small finance bank, AU’s journey has been defined by instinct to build steadily, think long-term and never overplay a shot. Edited excerpts:

Can you take us back to your journey and how AU started?

I come from a very humble background. My father was a government servant. There was no family capital, no business background, no exposure to entrepreneurship.

I played cricket for Rajasthan in 1990. I studied accountancy and graduated in 1994–95. At that time, life was about finding a livelihood, not about building a company. I started the NBFC [Non-Banking Financial Company] in 1996 —with support from a few HNIs [High Net-Worth Individual]. I guaranteed the safety of their capital and assured them of a minimum return. Any additional profit we’d share equally. That’s how my lending business began.

Vehicle financing was one of the key retail assets for any NBFC then. I observed players like Mahindra Finance and Gujarat Lease and realised that vehicle loans could be given at around 30% interest—short-term, secure, and profitable.

The first five to seven years were all about learning—how to raise money, lend money, design products, create systems where all stakeholders were happy. By 2003, we’d built an asset base of about ₹100 crore.

Then around 2003, HDFC Bank was looking for a partner to help them build their priority-sector asset base. We entered that arrangement as a channel business partner. The entire money came from the bank, but I provided a first-loss guarantee. We were the exclusive partner for Rajasthan.

Between 2003 and 2008, we worked exclusively with HDFC Bank in Rajasthan and Maharashtra. Working outside my home state helped me understand regional challenges and how to build a business in a new environment. HDFC Bank, even then, was a well-governed organisation. Their philosophy of building, scaling and sustaining a business was extremely solid.

What were the learnings from this period that you incorporated into your own strategy?

One big learning was diversification. Many NBFCs remain one- or two-product companies. But by 2015, we already had three or four product lines. For the first 12 years, we were primarily vehicle financers. Then, around 2010, I started micro-business loans or secured business loans.

After that, we launched a housing finance company, and then an insurance-broking venture. We even did a small portion of commercial lending. So, we diversified our risk—something many NBFCs don’t do.

In 2015, when the RBI issued guidelines allowing NBFCs to transition into banks, I took that as an opportunity. I’ve always believed an NBFC is a transactional model, whereas a bank is a relationship model. Relationships last longer; transactions don’t.

It wasn’t an easy decision—as an NBFC owner, I could have continued indefinitely as CEO without challenge. That’s where I learnt, from HDFC Bank again, to think not about today, but the next 20–30 years.

You started the housing, insurance and commercial-lending businesses around 2010–2012. Can you tell us more about them?

We had a housing arm called AU Housing, which we later sold around 2016–17 to comply with small finance bank guidelines. We also sold AU Insurance Broking because we weren’t allowed to continue that line once we became a bank.

But they played an important role in AU Finance’s growth—not just financially, but in broadening our understanding of different business segments.

For instance, if you don’t do housing, you never truly understand why people, especially in semi-urban and rural India, need loans to build their homes. If you don’t do insurance, you miss why people want protection for their belongings or lives.

When did you first envision that AU could actually become a bank?

When we became a small finance bank, we already had our eyes on a universal licence—it was the natural progression. But when I was running the NBFC, that thought didn’t cross my mind explicitly. It was an unsaid, unexpressed desire.

If you look at our journey—the first five years were driven by private money, with no certainty of scale. Then came the partnership with HDFC Bank, fulfilling their priority-sector requirements. After that, in 2008, we brought in private equity. Those private investors supported us immensely.

In 1996, when you raised money from HNIs, was it debt or equity? Did those investors see significant returns on their investment?

It was quasi-equity. Financial services never give huge profits to investors. We operate on 2–3% ROA [Return on Assets]; there’s no super-profit here. The advantage is scalability and sustainability because the sector is regulated.

In those early years, I gave my HNIs about 15% return on capital—which was good, considering bank deposits gave 8–10%. But that model wasn’t sustainable for long. Eventually, the HNIs wanted higher returns, which just wasn’t feasible.

That’s when I shifted to bank funding in 2003 through HDFC Bank. Even today, our banking ROE is around 15–16% on leverage of eight to nine times, earning 1.5–1.75% on assets.

How do you look at risk? What is your philosophy and strategy around it?

Being a chartered accountant [CA], maybe it’s a natural trait—I’ve always tried to understand risk first and then see how to mitigate it. If I can mitigate a risk, I go ahead. If I can’t, I simply don’t take it.

Can you share an example—maybe a decision where you differentiated between understanding and mitigating risk?

In the 2000s, microfinance was the big trend—everyone was talking about it. But I realised early on that microfinance was more of a process model, not a credit model. If a borrower defaulted, there was very little you could do—you couldn’t recover the money.

In contrast, if you lend against an asset, you can enforce recovery through that resource. The only real risk is if the asset itself doesn’t exist or is inaccessible. So, I built our lending model around that. That’s why, even today, around 95% of our book is secured and asset-backed.

In 2015, I also realised that beyond a point, the NBFC model itself carries structural risks—raising money from wholesale markets, people management issues, and overdependence on one or two products.

So, when the RBI came out with licensing guidelines, we decided to convert into a bank. That way, we could free ourselves from the risks of private debt or private equity and create a more permanent structure.

Since you were also a cricketer, do you approach risk like a batsman—playing the percentage game, as they say?

You’re taking me back to my old zone. We used to play early morning matches—around 8 or 9 am. At that time, you’re tentative, the ball is new, the bowlers are fresh, the pitch is lively. If you play a rash shot early on, you’ll get out.

But once you spend time on the pitch, the ball gets old, the bowlers tire, and the conditions improve. You learn when to play, when not to play, when to stay quiet, and when to take your time.

Business is exactly like that. You have to survive the early overs, understand the pitch, and then build your innings. Timing, patience, and reading the situation—that’s what separates a good innings from a reckless one.

For me, AU has always been about that balance—controlled aggression. You can’t rush into every opportunity that looks shiny. You need to know your strengths, stay disciplined, and play within your circle of competence.

There will always be tough days—like during COVID. I told my team then, “We just have to stay on the wicket. Don’t get out.” And you can see it in our numbers—after 2020, our deposits have grown four times in four years.

Last year too was uncertain—high inflation, tight liquidity, slow growth. Industry-wide credit growth dropped to about 10%, yet AU crossed ₹1 lakh crore in loans, assets, and deposits. How did you manage that, and how do you plan to sustain it in FY26?

Our size is still small. The entire deposit base of the Indian banking system is over ₹200 lakh crore, so we’re not even half a per cent of it.

That’s why even if the industry grows by 10%, we can easily grow by at least that much—and we can also take market share from others, simply because we’re smaller, hungrier, and more nimble.

Both the asset and deposit markets are massive—around ₹180 lakh crore and ₹100 lakh crore respectively. We’re just a 0.5% player in each.

We’re also well diversified, with around 30 products. So even if one sector, one product, or one geography doesn’t perform, others will make up for it.

I believe AU should grow at least two to two-and-a-half times the nominal GDP over the next five years. Our size itself is our opportunity.

As you transition from an SFB to a universal bank, it’s like moving from Ranji to test cricket. What kind of cultural or structural changes do you envision over the next 20–30 years?

I’d say the real transition—from Ranji to test—happened when we became a bank from an NBFC, not now. We’re already a scheduled commercial bank, and all regulations apply to us.

Culturally too, we’ve already become a bank. What defines a bank’s culture? A deep sense of customer protection, a strong understanding of regulatory discipline, inclusivity, and the belief that the platform we’re building is meant to last forever, a sense that we have multiple stakeholders—customers, employees, regulators, investors, communities—and that we must satisfy each of them. Those lessons are well-ingrained now.

For the past eight years, we’ve been playing test cricket—and not against easy opponents!

Despite that, we’ve crossed ₹1 lakh crore in deposits and assets, and built an all-India franchise with over 2,500 touchpoints serving everyone from microfinance borrowers to mid-corporates, from zero-balance account holders to those keeping ₹500 crore in deposits.

So, will there be any major change ahead?

No, because internally, we’re already structured like a universal bank. But yes, because public perception has shifted—people now say, “They’ve been promoted. They have great products. They have a bright future. We can bank with them.”

We don’t have to do much more—our tech is complete, our distribution is complete, our product portfolio is complete. Future products will come naturally as our cost of funds reduces.

Throughout a transformative decade which has seen everything from demonetisation to digital revolution, how does responsibility shape your vision?

The world is imperfect, and it will always be. We have to work through imperfections to reach excellence. Challenges will always exist—interest rate swings, inflation cycles, trade disruptions, or wars.

Globalisation today is at its peak. It’s not easy to build businesses anymore. But banks are different—they’re well-regulated, well-protected. Getting a banking licence is not easy, and that itself creates resilience. Some businesses will rise, others will fade—but a strong bank endures.

How do you see the tension between inclusion and premiumisation of banks over the next 10 years?

Many large banks are raising minimum balances because they’ve reached scale. If they don’t, their service quality may suffer. It’s natural at that size.

We are still small enough to serve everyone. It’s difficult to say where AU will be in ten years. What matters is balance, and the system itself keeps inclusion at the core.

Over the long term, say 10 years, how are you preparing the next line of leadership?

Succession planning is an ongoing, structured process—and a deeply emotional one for me as a founder. Structurally, we already have a deep bench: two deputy CEOs, plans for two executive directors, group heads, national heads—and a young team coming up behind them.

The average age of AU employees is between 20 and 30. Among our senior management partners—about 18 to 20 people—the average age is below 50. That gives us both maturity and energy.

Banking isn’t rocket science—it’s about principles: protecting customers, ensuring inclusivity, respecting diversity, safeguarding depositors, and enabling faceless yet personal banking. If future CEOs and executives understand those 10–12 principles, the institution will run smoothly.

Again, it’s like cricket—after Gavaskar came Sachin, after Sachin came Kohli, and now we have new stars like Abhishek and Jaiswal. Every generation produces its own talent, and institutions evolve with them. AU will be no different.

When the history of Indian banking is written, how would you like AU—and you personally—to be remembered?

If you ask me, I want to be remembered as a challenger—someone who built AU Bank; as a story that inspires every ordinary Indian to dream big, to stay on the right path, and to believe that it’s possible.