It was around 2002 that a real estate boom was taking shape after a decade of liberalisation. There was money sloshing around. And the high networth individual (HNI) backers of Sanjay Agarwal’s financing business in Jaipur were getting restless.

He had already been giving them returns of 15% a year since the mid-’90s, but now the HNIs were greedy for more. Agarwal, who had promised the investors a profit share over and above guaranteeing a basic return, realised that the maths was not going to work out anymore.

It would be too risky to juice out more yields from the business. So, he parted ways with the HNIs.

Talk to an entrepreneur who has made it big from scratch and they are certain to talk about their grand appetite for risk. But Agarwal almost despises it.

Wait ’n’ Watch

“If I can mitigate a risk, I go ahead. If I can’t, I simply don’t take it,” he says. It is something he learned the hard way while aspiring to become a professional cricketer.

The matches would typically start at 8 or 9am. At the beginning of an innings, the new ball would swing, and that’s when it was important to be patient. If he threw away his wicket early on, somebody else would score the runs when the going got easy.

“Business is exactly like that. You have to survive the early overs, understand the pitch and then build your innings. Timing, patience and reading the situation—that’s what separates a good innings from a reckless one,” he says.

“You can’t rush into every opportunity that looks shiny. You need to know your strengths, stay disciplined and play within your circle of competence. As a bank, we follow the same principle. Growth is important, but sustainable growth is what matters,” he adds.

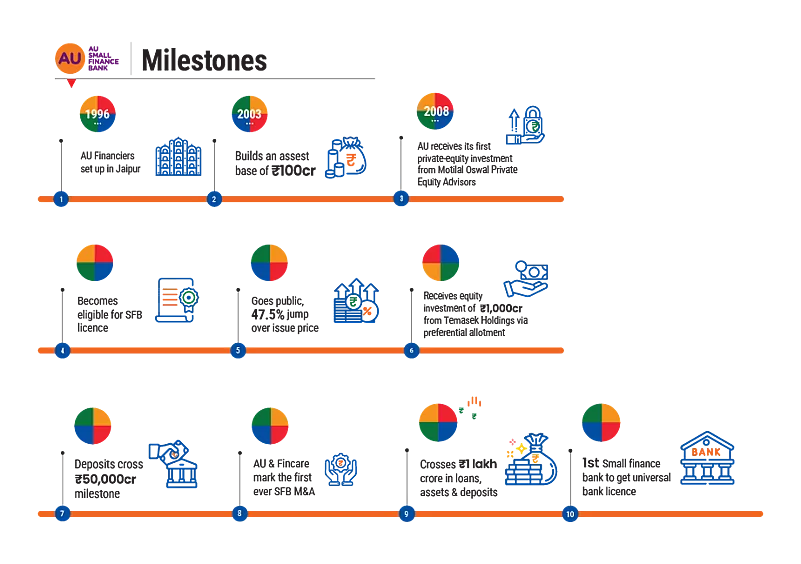

Perhaps that’s why for the first time in a decade, the central bank has made an exception for AU, the company that Agarwal founded 30 years ago, and given it an in-principle approval this year to graduate from a small finance bank (SFB) to a full-fledged one.

In a way, AU is already in the big league. With both deposits and loan book crossing ₹1 lakh crore, its market cap now not only towers over all its SFB peers, but also universal banks like RBL and Bandhan.

“The combination of good governance, compliance culture and profitability discipline made AU stand out. It’s one of the key reasons why they earned the RBI’s trust for a universal banking licence,” says Dinesh Khara, former chairman of state-run lender State Bank of India.

Many players have vied for a bank licence in the intervening years, only to be turned away. For one, the RBI does not want to grant a banking licence to any of the large family-run conglomerates in the country. And it holds any candidate to extremely high standards of being “fit and proper”. For example, a couple of years back, a non-banking financial company (NBFC) owned by Flipkart co-founder Sachin Bansal, who was enmeshed in a tax issue, couldn’t make the cut.

Circle of Competence

When Agarwal wound up his partnership with the HNIs, he had already made a name for himself in Rajasthan with a loan book of about ₹100 crore. More importantly, he had built a lending playbook: small loans that are secured by a revenue-generating asset could be given at about 30% interest.

“In the 2000s, microfinance was the big trend, everyone was talking about it. But I realised early on that microfinance was more of a process model, not a credit model. If a borrower defaulted, there was very little you could do. You couldn’t recover the money,” says Agarwal.

The focus was on self-help group formation, weekly meetings, joint-liability norms and operational discipline. The system worked as long as repayment behaviour was socially enforced. But the underlying credit risk—the borrower’s income volatility or the absence of collateral—remained largely unmitigated.

“In contrast, if you lend against an asset, say a vehicle, property or machinery and something goes wrong, you have recourse. You can enforce recovery through that asset. The only real risk is if the asset itself doesn’t exist or is inaccessible,” he adds.

That insight bore fruit in more ways than one.

Industry insiders say that one of the biggest reasons that AU became the first SFB among a dozen to get the go-ahead to become a universal bank is because secured loans comprise over 90% of its book. This has helped keep its non-performing assets under control even when macroeconomic conditions affected the recovery of its peers.

In April last year, ratings agency Icra said in a note that only AU SFB appeared clearly eligible for transitioning to a universal bank. While Ujjivan SFB met all the criteria pertaining to track record and performance, its high share of unsecured loans (about 70% as of March 2024) could hinder its prospects.

“The RBI has very specific requirements—five years of consistent performance, profitability, strong net worth, capital adequacy and solid credentials. But beyond that, if you look at AU’s asset quality, balance-sheet size and governance, they’ve demonstrated real strength,” says Arun Thukral, former managing director and chief executive of Axis Securities, an investment-services firm.

Around 2003, HDFC Bank was looking for a partner in Rajasthan to help build its priority-sector lending business. It wanted somebody who would manage distribution and lend responsibly, have some skin in the game.

AU fit the bill perfectly due to its experience of building an asset-backed credit portfolio. While the loan money came from HDFC Bank, AU provided a first-loss guarantee. Eventually, the partnership was also extended to Maharashtra.

“That period gave us immense learning. The first five years taught us how and where to lend; the next five taught us how to build distribution and manage scale,” says Agarwal.

Although the partnership ended in 2008, it became a turning point for AU. The validation from HDFC Bank and the resulting scale helped it snap up big-ticket funding from top private-equity players like Motilal Oswal, Warburg Pincus and Kedaara Capital in the following years.

Dose of Diversification

The period of 2008–09 was a difficult one for India’s auto sector. On one hand, passenger-vehicle sales took a hit as many white-collar jobs were lost due to the global financial crisis.

But that wasn’t all. Oil prices went through the roof as traders treated it as a hedge against the broader capital markets. In turn commercial-vehicle sales in India stagnated.

Meanwhile, vehicle financing still remained AU’s bread and butter. Agarwal realised around this time that it was too much of a concentration risk for the business. He had to diversify.

“Many NBFCs remain one- or two-product companies. But, we diversified our risk. Around 2010, we started secured business loans. After that we launched a housing-finance company and then an insurance-broking venture. We even did a little commercial lending,” says Agarwal.

“They played an important role in our growth, not just financially, but in broadening our understanding of different business segments. For instance, if you don’t do housing, you never truly understand why people, especially in semi-urban and rural India, need loans to build their homes. If you don’t do insurance, you miss why people want protection for their belongings or lives,” he adds.

This diversification also helped AU become one of the first NBFCs to be granted an SFB licence in 2015. To the RBI, it suggested that AU understood different risk pools and could prevent concentration blow-ups as a deposit-taking institution.

Over the past eight years, AU has made an effort to transform into a full-service retail bank: vehicle loans now account for roughly 32% of its assets, down from more than 50% in 2017, while business, home and personal loans together contribute nearly 45%.

Fee-based products such as credit cards, insurance distribution and forex services now generate over 10% of total income.

While AU diversified its products, the management was often questioned on its geographical footprint being heavily concentrated in a few states like Rajasthan, Gujarat and Maharashtra.

It acquired Fincare Small Finance Bank in 2024 to correct that. Fincare has brought with it a stronger presence in South India—particularly Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala—and a complementary deposit franchise.

“The merger expanded AU’s footprint, strengthened its capital and increased its relevance to the financial system. All of that helped it qualify for the universal-banking licence,” says Amit Jain, partner at consulting firm PwC.

Bench Strength

When Agarwal was considering applying for an SFB licence in 2015, it was not a straightforward decision. For one, it was still not clear if, how or when an SFB could become a full-fledged bank. Either way, he would have to give up the helm at some point due to RBI norms on a bank chief executive’s tenure.

That wasn’t all. As a requirement for transitioning into an SFB, the company would have to divest its stake from its very lucrative housing-finance and insurance-broking businesses. It was like giving up two birds in hand for one in the bush.

“It wasn’t an easy decision. As an NBFC owner, I could have continued indefinitely as CEO without challenge. But it was never just about me; it was about building something that would last beyond me,” says Agarwal.

“I also realised that beyond a point, the NBFC model itself carries structural risks: raising money from wholesale markets, people-management issues and overdependence on a few products. As a bank, we could free ourselves from the risks of private debt or private equity and create a more permanent structure,” he adds.

Once it was decided that AU would throw its hat into the ring, Agarwal knew that he would have to find a way to tame the most challenging risk there was: himself.

For this reason, it was not surprising when days after RBI’s go-ahead in August, reports emerged that AU SFB had enlisted the services of an executive-search company to devise a succession-planning strategy.

Over the past eight years, the company has invested deeply in creating a strong bench: it currently has two deputy CEOs, apart from several CXOs—all of whom join Agarwal to field questions from analysts after quarterly earnings.

The average age of its 50,000-plus employees is 31; while among the 18–20 senior management partners, the average age is under 50. It’s a conscious call to create a mix of maturity and energy.

The Show Goes On

“I’m not worried about succession. The market itself has an interest in ensuring continuity. Investors may place value on me today, but I’d rather they place it on the institution and its platform,” he says.

He points to Aavas, the home-financing arm that had to be sold off in 2016 in the lead up to AU’s application for an SFB licence. Kedaara Capital and Partners Group bought 90% of the company for ₹950 crore. “After I sold it, that company became one of the most expensive stocks in the segment,” he says with a hint of pride in his voice.

For him, it is about attracting high-calibre people, aligning them with the institution and enabling them to deliver.

“It’s like cricket again—after [Sunil] Gavaskar came Sachin [Tendulkar], after Sachin came [Virat] Kohli, and now we have new stars like Abhishek [Sharma] and [Yashasvi] Jaiswal. Every generation produces its own talent, and institutions evolve with them. AU will be no different,” he adds.

In the same vein of analogy, the risk appetite from Gavaskar to Abhishek has undergone a sea change every generation. Will it be the same for AU?