IndiGo Airlines’ flight cancellations have exposed India Inc’s duopoly problem.

The episode, flagged by experts and even a parliamentary committee, highlights the CCI’s reactive approach to regulation.

We explore whether a resource-constrained competition regulator can tackle this challenge head-on.

On December 5, IndiGo airlines, which carries two out of every three domestic air travellers in India, cancelled over half of its 2,200 or so daily flights. The chaos it triggered was unprecedented: large piles of baggage inside airports, angry passengers shouting at ticket counters and tearful ground staff struggling to cope.

IndiGo blamed the cancellations on the alignment of several precipitating factors, especially the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA)’s new Flight Duty Time Limitations (FDTL) norms that restricted pilot duty hours. The situation in India’s airports became so unstable that the Ministry of Civil Aviation was forced to roll back the FDTL norms and delay their implementation till February 2026. The events also triggered an investigation by the Competition Commission of India.

To some, the entire turn of events may look like the result of a misstep by an overzealous or out-of-touch regulator. However, critics, including pilots’ associations, have suggested that what happened was no accident, but engineered chaos designed to strong-arm the government into withdrawing the flight duty limitations hostile to corporate profits. Or, as the Airline Pilots' Association of India (ALPA India) put it: it was “an artificial crisis engineered to exert pressure on the government for commercial gain under the pretext of public inconvenience”.

The Rise Of Duopolies

Yet, the incident has aspects that go beyond a private corporation’s response to inconvenient legislation: It also lays bare the pitfalls of concentrating market power in the hands of one or two players. Specifically, many believe the incident is only the latest reminder of a lingering problem with the functioning of India’s competition regulator: how it waits for a crisis to act, instead of ensuring the health and competitiveness of a sector through continuous monitoring and interventions. They argue that the Competition Commission of India has failed in its primary duty, to ensure healthy levels of competition in the market by preventing unbridled concentration of market power.

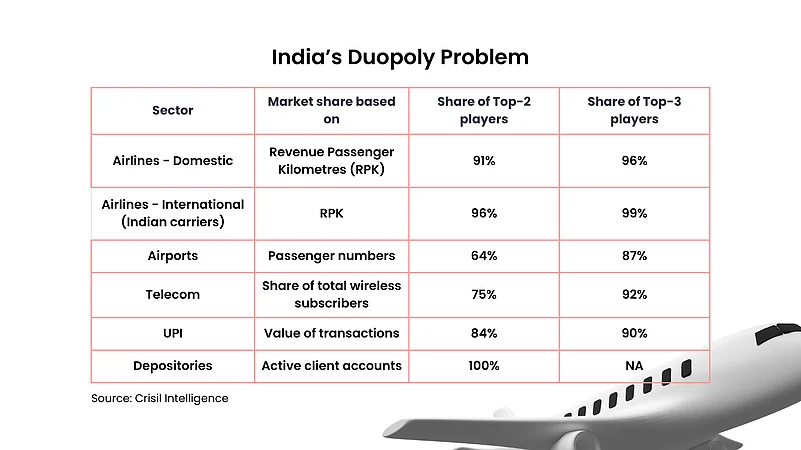

To buttress the argument, they produce data showing rising market concentration in several key sectors of the Indian economy. They point out that heavy market concentration is not visible in just the airline sector, where the top two players—IndiGo and Tata—control 91% of revenue passenger kilometres.

In the airports segment, the top two operators handle 64% of passengers. In telecom, the top two account for 75% of the total wireless subscriber base. In digital payments, the top two UPI players handle 84% of transaction value. In the stock market depository business, two players account for the entire market.

In other sectors, concentration is a little less pronounced but still present. For instance, in the paints sector, Asian Paints controls about 52% of the market, and is facing an antitrust probe after recent entrant Birla Opus complained to the CCI about market manipulation.

In ports, Adani Ports (APSEZ) leads with about 27% market share by cargo volume, significantly ahead of competitors like JSW Infrastructure, APM Terminals (Pipavav) and Gujarat Pipavav (GPPL). The Adani Group company operates 15 domestic ports and terminals across India.

Critics of the CCI’s ‘passive’ approach allege that concentration of power has not only given these players enormous control over pricing, but has reduced alternatives and capacities, leaving consumers and the state exposed.

Deepening Dependence

The critics point out that while the CCI is fully aware about its duty to protect competition when it comes to approving mergers and acquisitions, it seems to be rather oblivious to the phenomenon of creeping dominance.

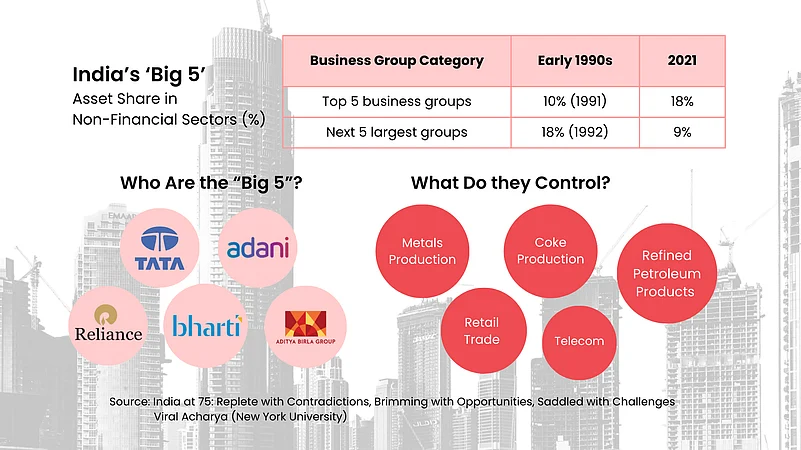

In his papers, Viral V Acharya, former deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India, has traced the phenomenon of creeping market dominance after India’s liberalisation reforms in the early 1990s. He chronicled the increasing power of top five Indian conglomerates—Reliance Industries, Tata Group, Aditya Birla Group, Adani Group and Bharti Telecom—which he calls the “Big 5”, in non-financial sectors.

In his paper, he argues that their share in total assets of the non-financial sectors rose from 10% in 1991 to nearly 18% in 2021, while the share of the next five largest business groups fell from 18% in 1992 to less than 9%.

“The Big 5 grew not just at the expense of the smallest firms, but also of the next-largest firms. It is possible that some of this growth in the share of the Big 5 is due to their ability to acquire relatively large defaulted companies that were filed to the IBC following the Reserve Bank-initiated clean-up of the banking sector in 2017–18,” Acharya wrote in a 2023 paper titled “India at 75: Replete with Contradictions, Brimming with Opportunities, Saddled with Challenges”.

However, increasing market share only paints a partial picture of the dominance of these groups. In addition to driving their overall growth, these groups have also been narrowing their attention onto certain key industries, he noted.

Acharya noted that until 2010, the Big 5 were focused on a varied number of sectors. However, starting in 2015, they began acquiring larger shares in certain key sectors where they were already present, which makes their presence and potential control more effective. Among the sectors subjected to their increasing domination are metals, coke and petroleum refining, retail and telecommunications.

Acharya has not been alone in flagging risks around market domination and concentration. Just four months before the IndiGo crisis, the Lok Sabha’s Standing Committee on Finance warned the CCI about the growing problem of duopolies.

“In critical sectors like telecom, only two major players remain, and now aviation [has also followed suit]. The problem has shifted from monopolies to duopolies,” the committee, led by BJP MP Bhartruhari Mahtab, said in August 2025. It asked the regulator to outline its long-term strategy to regulate and mitigate the rise of duopolies in critical sectors.

In its response, the CCI had said: “The conduct of duopolies can be examined under the framework of Section 3 of the Act, which covers all anti-competitive agreements, including horizontal and vertical agreements.”

Consequences of Concentration

The rising dominance and market concentration in key sectors can have a dampening impact on competition in the market, which can in turn lead to rising inefficiency reflected in high prices and a lack of innovation and consumer choice.

“Goods prices in India remained elevated even after global goods inflation softened in 2022 when global supply-chain issues eased. Indeed, goods inflation momentum in India in 2022 remained positive, whereas its global counterpart was negative,” noted Acharya and coauthor Rahul Singh Chauhan in a paper last year.

The ex-RBI official added that goods inflation in India is likely to persist as margins of manufacturers are substantially high due to the dual factors of tariff-based protection from imports and market power arising from rising concentration.

Headline consumer price inflation excluding food and fuel components also remained persistent at around 6% during 2020–22. “A possible reason for this persistence in core inflation is that consumers in India do not seem to be fully benefiting from input price declines, which may be due to greater pricing power in its increasingly concentrated industrial organisation structure,” he noted.

Envisioned Role of CCI

It was exactly to prevent this kind of concentration, and to ensure proper competition and consumer choice, that the Competition Act was passed in 2002. Acting on the Raghavan Committee’s recommendations, Parliament designed the CCI as an independent, expert, quasi-judicial authority with investigative, adjudicatory and advocacy functions.

Unlike the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act of 1969, the new law was envisioned as a modern regime that regulates conduct, not mere dominance, said B. Shravanth Shanker, Advocate-on-Record, Supreme Court of India. The shift was doctrinal as much as institutional, moving from monopoly control to an effects-based assessment of practices that cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition.

The Act bestowed upon CCI a broad range of suo motu, advisory and advocacy powers and envisioned the agency as one actively monitoring the market through various studies, surveys and analyses. "In this sense, the CCI was conceived as a proactive guardian of the competitive process rather than a passive tribunal reacting to private disputes," said Shanker.

Reactive Regulation

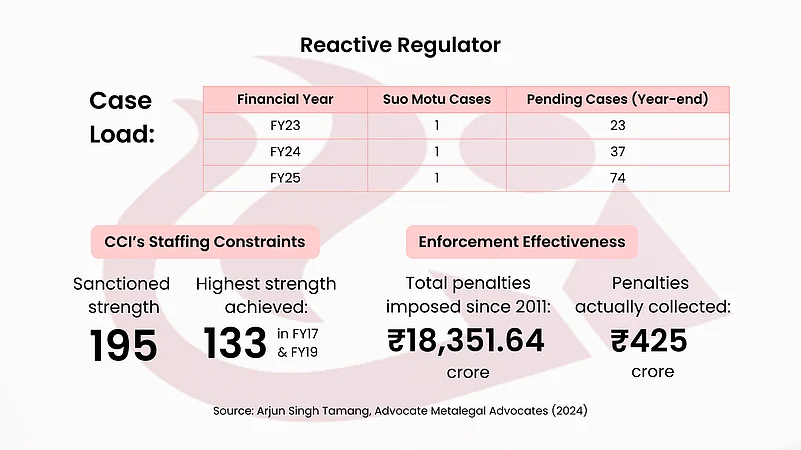

However, the CCI has struggled to live up to its mandate of being an agency actively ensuring market health through suo motu market research and studies. In recent years only one such study has been released publicly—on artificial intelligence (AI), which came out earlier this year.

“The CCI has functioned more as a reactive tribunal than as the proactive market regulator that its statutory design clearly contemplated,” said B. Shravanth Shanker, Advocate-on-Record, Supreme Court of India, adding that the aviation sector illustrates the cost of this posture, where dominance consolidated over time without timely regulatory engagement.

The last time the CCI investigated the aviation market was in 2015, when there were at least five large players. After six years of investigation, however, the regulator found no evidence of collusion among airlines on air ticket pricing.

Nearly a decade later, two of those five airlines, Go First and Jet Airways, have collapsed, while SpiceJet operates on a much smaller scale than it once did. A new entrant, Akasa Air, has so far made little dent in IndiGo’s dominant position.

“The moot point is whether they (CCI) should have looked at this earlier and seen whether there was abuse or not… perhaps there were no complaints,” Ashok Chawla, former chairman of the Competition Commission of India, told Outlook Business.

Alay Razvi, managing partner at Accord Juris, agrees that the commission has been somewhat circumspect in the use of its powers. "Although the Act empowers it to initiate suo motu inquiries, conduct market studies and intervene early against emerging concentration, these powers have been sparingly used,” he noted.

Data show that the CCI took up one suo motu case each year for the past three years, compared to an average of about three cases referred by central or state governments. Notably, data from CCI’s annual reports show that it received three antitrust complaints in FY24, though there are no further details on what these complaints were about or what happened to them.

Instead of proactive monitoring, said Razvi, CCI has primarily relied on informants and adversarial proceedings, responding to violations after market harm has already occurred. “This has limited its ability to pre-empt structural concentration, particularly in fast-moving sectors such as aviation, telecom and digital markets,” he said, adding that more than one review has pointed out that the CCI lacks continuous market surveillance and sector-wide monitoring mechanisms.

Lack of Resources

Part of the reason for the lack of proactive interventions may be related to a lack of resources.

Since FY15, the CCI has yet to operate at its full sanctioned capacity. As per the latest data available, the CCI’s highest strength, recorded at 133 members, constituted only 67% of its authorised capacity during FY17 and FY19. The body's total sanctioned strength is 195.

The resource crunch sometimes extends right to the top, such as when CCI chairperson Ashok Kumar Gupta retired in October 2022. The government did not fill his vacancy for nearly seven months. During this period, the regulator also suffered from a lack of quorum (the CCI needs at least three members to approve mergers or pass orders). This delayed some high-profile investigations involving major technology firms such as Google and Apple.

Former CCI chair Chawla said there was also an issue in terms of the time taken in enforcement, which he described as “rather long” and said it could be due to staff shortages or the time taken for investigations. Since 2011, the CCI has imposed penalties totalling ₹18,351.64 crore but has managed to collect only ₹425 crore, which is just 2.3% of the total, the report noted.

According to Arjun Singh Tamang, Advocate at Metalegal Advocates, who brought out a report on the problems faced by the CCI in 2024: “The real issue with the CCI is that the statute has given it only adjudicatory power rather than enforcement power. That adjudicatory power is also weakened due to a lack of human resources,”

Ease of Doing Business and National Champions

Finally, beyond the problems of approach and resource availability, the CCI’s functioning also seems to have been impacted by the ‘progress at a fast pace’ agenda of the executive branch.

An expert, who did not want to be named, told Outlook Business that the focus on “ease of doing business” has trickled down into the thinking and working of the Commission. As a result, it appears to be more engaged in the quick disposal of mergers and acquisitions, while enforcement seems to have taken a back seat.

Acharya identified this problem as stemming from the “national champions” policy that depends on a handful of large conglomerates to implement the government’s vision of fast economic development. In return, they are given preferential project allocation, regulatory forbearance and high tariff protection.

“The national champions are expected to deliver on government-desired projects (especially in infrastructure) but receive, as a quid pro quo, among other benefits, preferential allocations, access to government, bypassing of bureaucratic hurdles and a steady garnering of market power within and across industrial sectors,” his 2024 paper explained.

The push to build “national champions” is often compared with South Korea’s ‘chaebol’-led model, where the likes of Hyundai and Samsung were subsidised to grow into large conglomerates. However, there are key differences that cast doubt on its effectiveness, according to Acharya.

Unlike Seoul, New Delhi has protected large conglomerates with high import tariffs, limiting exposure to global competition and keeping most Big 5 revenues domestically focused, except in tech services and parts of e-commerce.

Moreover, South Korea also paired its champion strategy with deep reforms in land, labour, power and finance to foster strong domestic competition, whereas India’s reforms outside the financial sector remain incomplete, according to the former central banker. He asks whether India’s increasing industrial concentration is economically efficient, as it is marred by weaker investment, lower firm entry of newcomers and rising barriers to competition.

Finding the Right Balance

In the end, the key question is: What can the CCI do in a climate that prioritises clearances and growth at all costs, and whether a competition regime designed for markets with competing firms can coexist with a development strategy that prioritises scale.

The CCI is undeniably a strong institution, says Meghna Bal, director of Esya Centre, a technology policy think tank based in New Delhi.

“As a horizontal regulator, it possesses wide-ranging investigative, adjudicatory and remedial powers that cut across sectors. However, the strength of competition institutions cannot be assessed in a blanket or abstract manner, divorced from market realities and policy context,” she noted.

She added that in certain markets, softer or more deferential intervention may be warranted to allow efficiency gains, economies of scale or sectoral stability, while in others, stringent enforcement is necessary to prevent the entrenchment of market power and foreclosure of competition.

“What therefore becomes the relevant benchmark is not the formal authority of the institution, but its institutional competency — that is, its ability to calibrate enforcement intensity in response to evolving market structures,” Bal said.

When asked about CCI’s enforcement power compared to its foreign counterparts, she noted that “the CCI is much more reasonable and open to understanding market dynamics than the competition regulator in the EU, particularly”.

However, she added that the capacity of the CCI needs to be bolstered—more manpower, more experts and more funds. As a horizontal regulator whose oversight spans all markets, it needs greater resources.

“Greater reliance on market studies, deeper engagement with sectoral regulators and continued investment in economic expertise would assist the Commission in addressing complex market structures at an early stage,” said Tushar Kumar, advocate at the Supreme Court of India.

As Acharya points out, in India, the risks from rising market domination is not restricted to the stifling of innovation and consumer choice, but has socio-political aspects due to the fact that most of the increasing market power ends up in the hands of a handful of conglomerates. These risks include crony capitalism and political connections, inefficient project allocations, related-party transactions within corporate groups, over-leveraging due to an implicit too-big-to-fail perception, and key-family risk in operational efficiency.

For now, the IndiGo episode has exposed the risks of an economy where competition is thin and regulatory intervention arrives only after disruption. Whether this crisis pushes for such a reform remains to be seen.