Organisations today grapple with a range of challenges. While navigating the landscape of the future of work marked by demographic shifts, disruptive technologies, workforce restructuring and the urgent need for rapid upskilling, they often find themselves in uncharted territory. In such volatile conditions, attention naturally turns to leaders to steer organisations towards sustainable and inclusive growth while remaining insulated from adverse external influences.

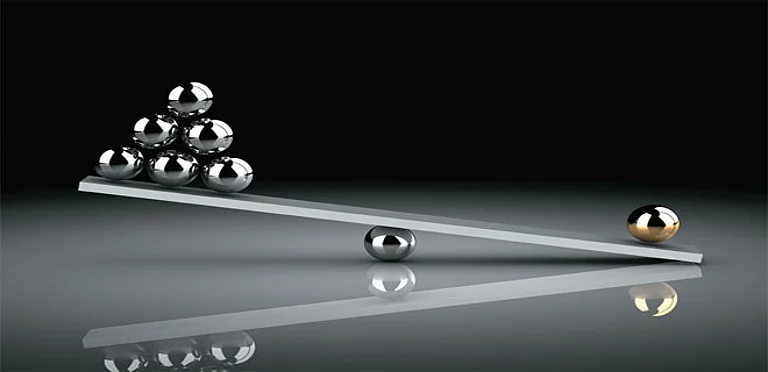

Practitioners and scholars of leadership agree on one point: prudent decision-making is the need of the hour. Leaders must demonstrate patience and a deep commitment to understanding problems and developing imaginative, sustainable solutions. Yet, more often than not, decisions are made in haste not out of choice but because the pace of business demands it. This tendency may signal a lack of strategic foresight, where the pressure to appear decisive leads to biased thinking and logical fallacies.

This gap between ideal decision-making and reality became evident during a recent executive training programme that we conducted, a participant raised a pressing concern observed across industries: the decline of critical thinking and the rise of unsustainable decision-making. He remarked, “While we see the presence of confirmation bias in managerial decision-making, we do not know how to tackle it.” His concern is valid.

The Cost of Hasty Thinking

The prevalence of confirmation bias and other cognitive distortions reflects a stifling environment that undermines trust, constrains creativity and hampers innovation. Although this insight came from a participant employed in a public sector undertaking, similar issues are pervasive across sectors. The erosion runs deep, embedded in both our professional and everyday lives. This brings us to a fundamental question—why is critical thinking so highly relevant in the workplace today and for the future?

Critical thinking is often described as a soft skill but in practice it equips individuals to challenge ideas and assumptions rather than accept them at face value. It enables people to examine their reasoning, refine it and make better decisions. Over time, it has evolved into a survival skill, especially as extreme automation threatens millions of jobs across industries.

According to The Future of Jobs Report 2025 by the World Economic Forum, 69% of employers view analytical thinking as a core skill for the future workforce. The OECD Employment Outlook 2023 report also highlights that critical thinking is in high demand in the age of artificial intelligence (AI). These reports make it clear that critical thinking is no longer optional. In times of disruption, managers must evolve from task supervisors into adaptive leaders capable of maintaining decision hygiene and navigating uncertainty.

The challenge, however, lies with the decision-makers who often rely on intuition rather than reflection. Consider a scenario where a manager favours a candidate simply because they share similar beliefs. In such cases, hiring for “culture fit” becomes a proxy for bias. These managerial heuristics or mental shortcuts can be particularly harmful when an organisation claims to support diversity, equity and inclusion. Strategic failures frequently arise from unmanaged biases rooted in wishful thinking and flawed logic. When these biases go unaddressed, value creation for organisations and their stakeholders remains unrealised.

This raises a crucial question: If individual decision-makers are so susceptible to bias, can institutions do any better?

In an interview, Nobel Prize-winning psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman observed that he has more confidence in the ability of institutions to improve their thinking than in the capacity of individuals to do the same. Individuals struggle to maintain decision hygiene due to cognitive limitations, emotional variability and bias. In contrast, organisations have the ability to design structures that promote better decision-making. Still, collective intelligence often fails not because it is absent but because it is clouded by unchecked noise and deeply ingrained biases.

This gap between potential and practice becomes stark when we examine real-world examples of institutional decision-making. Consider the case of the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF), created by the Government of India in 2016 to foster healthy competition and enhance institutional performance. Despite its objectives, NIRF has faced criticism for its lack of credibility. A recent study highlights how blind acceptance of self-reported data undermines the reliability of the rankings.

Building Better Decisions

Although the framework sets objective criteria, the results frequently show significant anomalies. In the absence of robust mechanisms to verify institutional claims, manipulated data may encourage unethical practices. For example, an institution may inflate its faculty–student ratio by misreporting visiting faculty as permanent, demonstrating a form of reporting bias. This unchecked decision-making is only a small part of a larger problem.

This issue is not limited to education rankings. It reflects a broader organisational malaise: the persistence of motivated reasoning and the lack of mechanisms to counter it. Many organisations have yet to confront the fundamental issue. Despite claims of restructuring and leveraging AI tools for data-driven decisions, they remain vulnerable to compromised thinking. A persistent problem in boardrooms and team meetings is flawed reasoning: “I want ‘P’ to be true; therefore, ‘P’ is true.”

This logical fallacy has permeated organisational culture, revealing systemic vulnerabilities and raising ethical concerns about decision-makers who may be driven by motivated reasoning. When an individual pushes a questionable agenda for personal gain, whether financial, reputational or otherwise, it reflects a deeper problem of self-interest influencing strategic decisions. Unfortunately, the lessons from history, such as John F Kennedy’s failed Bay of Pigs invasion (a failed attempt by the US to overthrow the communist government in Cuba), appear to have gone unheeded.

What lies ahead is the need for decision-makers to become more self-aware. Many tend to overestimate their capabilities, rely on past successes and ignore evidence that challenges their assumptions. We must move beyond wishful thinking and stop overvaluing the resilience of businesses in the face of market disruptions. The story of Naresh Goyal, founder of Jet Airways, offers a cautionary tale. At a time when the aviation sector was shifting toward low-cost models, he remained in denial and failed to recognise the growing dominance of carriers like IndiGo and SpiceJet. Anchored in past success and brand loyalty, he continued to pursue a full-service model despite mounting signs of irrelevance.

History repeats itself as start-ups across sectors struggle to justify their niche. Time and again, we see decisions promoted as beneficial yet lacking long-term viability. It could be an executive from the banking industry highlighting strong performance metrics while ignoring poor asset quality or an academic institution spending extravagantly on branding while neglecting faculty recruitment, research ecosystem and curriculum innovation. To address such challenges, organisations must confront flawed thinking directly. A robust decision-making process requires strategic dialogue, open deliberation and a culture that values dissent. Diversity of thought must be embraced not penalised to ensure sustainable outcomes.

There are ways to overcome these persistent biases. If Kennedy’s failure taught us anything, it is the importance of inviting diverse perspectives and fostering open intellectual exchange. When individuals bring different experiences and viewpoints, their contributions enrich decision-making. Rather than striving for conformity, organisations should encourage the formulation of alternative hypotheses. Instead of gatekeeping ideas, they must recognise, cultivate and evaluate arguments that strengthen critical thinking. As Aristotle reminds us, “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.”