Nike’s famous tagline ‘Just Do It’ has a gory history. The slogan writers were inspired by the last words of a man who was facing a firing squad, in the seventies, after committing double murder. It could be considered a brash move by a responsible company, the choice of these words. But the American multinational has built its brand through its association with sports. And, on the field, defiance is celebrated.

In India, Nike chose to ride the cricket frenzy. It paid big money to become the official kit sponsor, which was meant to help with branding and which gave it the apparel-merchandise licence. Then the company expanded its retail presence aggressively and settled down to collect the spoils. Only, the till didn’t ring as much. Indians may paint their faces, cry when the team wins or fly across borders to watch a match, but they still look at the price tag before buying shoes. The $36-billion Nike’s strategy — of riding into every market on the back of a sport — has failed badly in India.

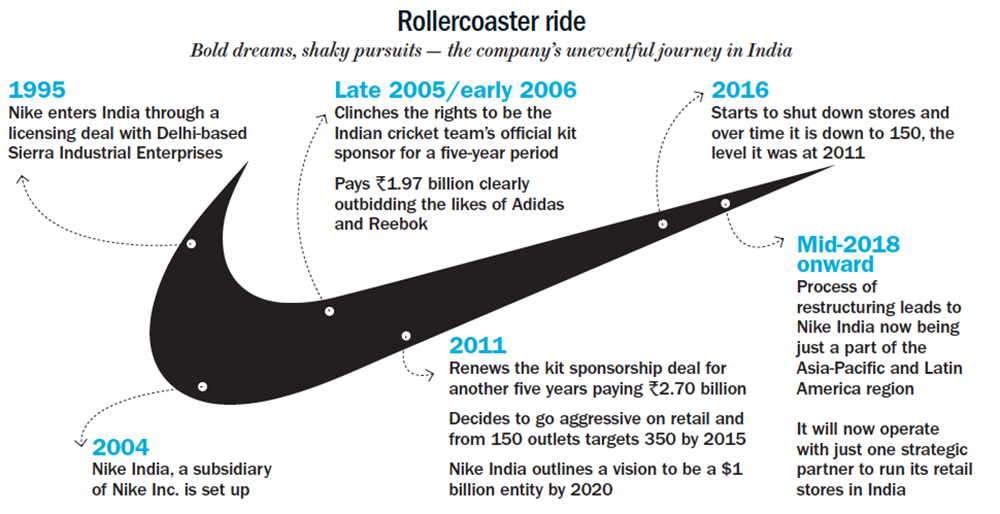

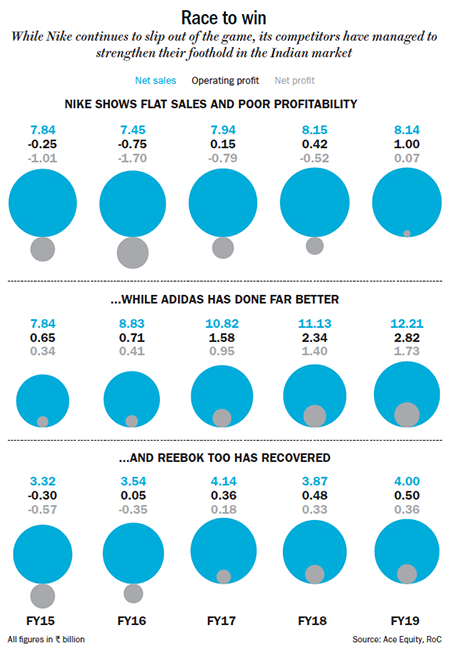

The company hadn’t registered a net profit since 2006, and last fiscal it broke that jinx with a modest Rs.76.7 million. Its revenue for 2019 was Rs.8.14 billion, a number that has virtually remained unchanged over the past four years. Today, Nike India has just 150 outlets after having shut down around 200, a scaling down that began in 2017. The company has no dedicated country head but one in Singapore who oversees the Asia Pacific and Latin America region.

Outlook Business did send a detailed list of questions to Nike India. In an emailed response, the company said, “Nike does not comment on business for specific countries and we will not participate in this story.” So, we are on our own here, but thankfully we have former employees of the company, experts and analysts to help us construct a reliable picture.

Stepping foot

Stepping foot

Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place to start, as Julie Andrews sang. The brand has been around in India for over two decades now. In 1995, it entered the market through a licensing deal with Sierra Industrial Enterprises (See: Rollercoaster ride). A decade later, it set up its subsidiary Nike India. And a year after that, it decided to hitch its wagon to cricket. In 2005, it paid Rs.1.97 billion to BCCI for official kit sponsorship rights for a five-year period. Rivals Adidas and Reebok were more measured, with the first bidding Rs.1.28 billion and the latter Rs.1.19 billion. (The two were functioning as different entities, even after their merger.)

Nike had reason to be bullish. In other markets, such as US, Europe and Brazil, the idea of attaching itself to a sport has worked beautifully. In Brazil, the company has built its brand around football ever since the 90s. It was also a market the competition had overlooked, in favour of larger markets, and was serving this through exports routed through Southeast Asia. But Nike began working with football clubs and signing on Brazil’s best players, and it even sponsored the Rio Olympics in 2016. Today, Brazil alone is well over a $1 billion market for the brand.

The company went to China in the 1980s, using it as a manufacturing base initially. However, it has since been converted into a lucrative market, yielding revenue well in excess of $5 billion in 2018 (footwear brought in $3.5 billion with apparels and accessories $1.5 billion). “The turnaround began a decade ago by opening more retail outlets and smartly working with local football clubs. Today, Nike has a market share of at least 20% in China,” says Matt Powell, senior industry advisor - sports, NPD Group, a US-headquartered market research company. Adidas has a market share of 15%, Anta 10-12%, and Li Ning, Xtep and New Balance together 15%. Other brands make the remaining 35-40%.

Howzatt!

But the cricket strategy did not pan out well in India. During 2006-2011, the contract period with BCCI, Nike remained in the red. Revenue grew from Rs.1 billion to Rs.2.5 billion. Even at its peak, revenue from cricket (apparel, merchandise and equipment put together) was never more than 2% of the total. The largest share was shoes at 60%, followed by apparels accounting for 35% and then accessories for the other 2-3%. This should have put Nike off cricket forever; you know ‘once burned twice shy’. But in 2011, India won the Cricket World Cup and there was a slight increase in the demand for Nike’s cricket products. That revived its hopes, and when the contract with BCCI came up for renewal, Nike snapped it up.

“The management was for some reason convinced that cricket could still be a big story and decided to go for it,” says a former Nike official. At a time, when no other sportswear company bid, Nike clinched it quite easily for Rs.2.70 billion. “Adidas, Reebok and Puma put their money behind IPL, starting 2008, by sponsoring teams. IPL was a safer bet with a deal being signed at just Rs.20-30 million per team,” the aforementioned source adds. In all, Adidas spent around Rs.150 million in the first year for six teams and Puma Rs.20-30 million for one. Nike’s investment in cricket, more than 20x that of its competitors, didn’t yield proportionate return.

The former Nike official says that the company misread the market badly. Sports participation is low in India, even in local cricket clubs, and those who play simply buy an affordable pair. Nike would be priced 3-5x that. Prateek Srivastava, co-founder of brand consultancy ChapterFive Brand Solutions, says, “India is not a sporting nation, and people buy expensive shoes because they want to look good in it. This is very different from the West where people buy a pair of Nike shoes to play a particular sport.” Then, there are quirks. “A sports enthusiast, even a cricket lover, will spend on a Chelsea or Barcelona jersey but not on cricket. That peculiarity in the Indian market was something Nike missed,” says another former official. Then, there was the overestimation of the opportunity. In the vision statement outlined for India in 2011, the revenue target set for 2020 was $1 billion. But in 2011, Nike India had revenue of just Rs.2.50 billion. In fact, the entire Indian market for branded cricket items is not even worth $100 million today. Besides an extraordinary transformation, Nike India would have also needed cricket to take off manifold to achieve its grand ambition.

Branding around cricket in India was anyway never going to be easy, according to Srivastava. There are too many companies, across categories such as soft drinks, television and even cement, trying to latch on to the sport’s popularity. “Not all of them are necessarily linked to the sport and that makes the process of building a brand around cricket extremely difficult,” he says. Simply put, to build a solid brand, every game must remind you of associated things such as sneakers or an energy drink, not a sack of cement or securing your financial future. That scrambles the messaging for all.

Around the time Nike decided to place its faith once more on cricket, it also decided to increase its retail presence in a hurry. Nike is known across the world for having a large number of stores, and this is done to be close to the consumer. Usually the company takes time to build that retail network, but that patience was conspicuously absent in India. Perhaps, Nike was that certain of its pitch. In 2010, the brand had a little over 150 retail outlets, and the top management here decided to ramp up the number to 350 by 2015. They could have been in a tearing hurry because the combined reach of Adidas and Reebok was at over 1,000 stores even in 2010.

Over the next four years, Nike decided to go the whole hog, even into smaller towns. It forayed into Tier 2, 3 and 4 centres, such as Rourkela, Bhiwandi, Sri Ganganagar, Hissar and Rohtak. If the average size of an outlet in the metros and other large centres was 1,000-1,500 square feet, it was no more than 800 square feet in these smaller places with Nike shoes sold for Rs.1,500-3,000.

Backtracking

To be fair, business did take off. Take a centre like Rohtak in Haryana. In 2015-16, Adidas was clocking a monthly revenue of Rs.2.5 million, while Nike was doing anywhere between Rs.800,000 to Rs.1 million. “Nike was still profitable at that level and there was potential to grow,” says an industry tracker. Building a brand in smaller centres takes time and Adidas was being rewarded for its patience, he says, adding Nike soon got tired of the wait. By 2016, the process of shutting down its stores had started, with almost none existing in these smaller centres today.

In urban centres, the expectation was that exclusive Nike stores would bring in 20-25% of the revenue, while the rest would come from large department stores. It mirrored how business was done globally. According to Rajiv Mehta, CEO, Stovekraft and ex-MD, Puma Sports India, this is one of the few countries where Nike was forced to open smaller stores due to real estate economics and purchasing power. “Eventually though, they want India to follow the global mandate which means smaller stores will not work,” he says. A former Nike official quoted earlier says strategic meetings were held to counter the imminent entry of sports speciality stores (such as Decathlon and GoSport). “However, none of the counter strategy was implemented. In the end, the stores did not evolve nor did the sales numbers improve exponentially,” he says (See: Race to win). NPD’s Powell says that in India, the company was confronted by a lack of organised retail.

In urban centres, the expectation was that exclusive Nike stores would bring in 20-25% of the revenue, while the rest would come from large department stores. It mirrored how business was done globally. According to Rajiv Mehta, CEO, Stovekraft and ex-MD, Puma Sports India, this is one of the few countries where Nike was forced to open smaller stores due to real estate economics and purchasing power. “Eventually though, they want India to follow the global mandate which means smaller stores will not work,” he says. A former Nike official quoted earlier says strategic meetings were held to counter the imminent entry of sports speciality stores (such as Decathlon and GoSport). “However, none of the counter strategy was implemented. In the end, the stores did not evolve nor did the sales numbers improve exponentially,” he says (See: Race to win). NPD’s Powell says that in India, the company was confronted by a lack of organised retail.

This also meant that the brand’s premium positioning did not fly in this market. Nike was always priced 30% more than the competition. Powell says, in the US too, its shoes are sold at a minimum price tag of $100. “In any part of the world, Nike will operate in a limited number of cities and deal with an evolved consumer,” he says. But India demanded an affordable range, priced below Rs.3,000, which was new to Nike and its image took a bit of a beating. Hemchandra Javeri, who headed Nike’s India operations in the early 2000s, says that it was not just the pricing. “Even when high discounts were offered, sales never peaked. Indian consumers are not just price-sensitive but need to see value as well,” he says. Javeri insists the swoosh always enjoyed high brand-recognition in India even in the early stages. “However, most consumers do not understand or connect with the brand. It is a case of high brand recall not translating into a strong business,” he says.

Another compromise Nike had to make was with online retail. In 2011, the management had decided to never let revenue from this channel cross 5%, since that would have affected its gilded image. But shopping behaviour was changing rapidly in India and pressure to increase sales was on Nike. Today, around 20% of Nike India’s revenue comes from the online channel – no different from Adidas’ number but much lower than Puma’s 50%. Finally, the company decided to diminish its focus on India. From a vast network of 80-90 franchisees and another 25 distributors, Nike is down to just one strategic partner, the Delhi-based SSIPL. It will run Nike’s retail store with the likes of Flipkart and Amazon catering to online demand. The internal restructuring means Sanjay Gangopadhyay, earlier the head of India, is now based in Singapore overseeing other markets in addition to India. Mehta is convinced India will be a regional play for Nike. “It is no different from having a regional office in an Indian zone,” he says. The company may have strode into the market with the ‘Just Do It’ swagger, but today it has thrown its hands up in the air with ‘can’t do it’.