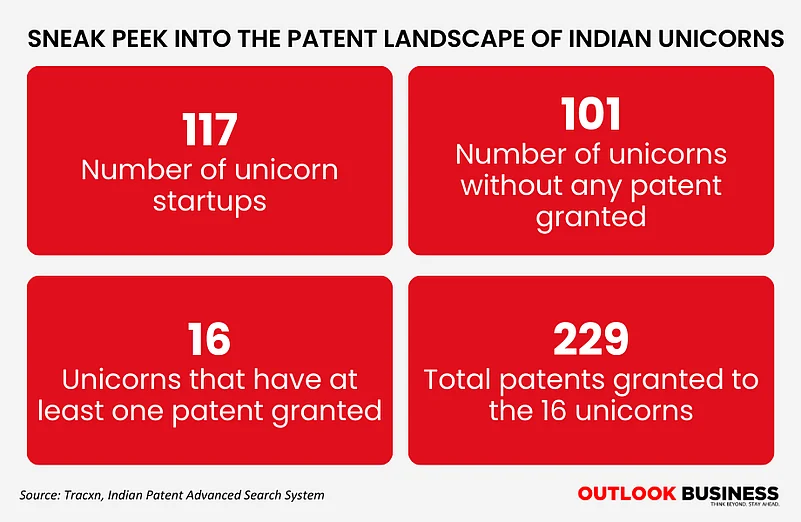

India’s startup boom has created 117 unicorns—startups valued at over $1 billion each—making it the world’s third-largest tech ecosystem. But scratch beneath the surface, and an unsettling trend emerges: of these 117 unicorns, a staggering 101 hold zero patents.

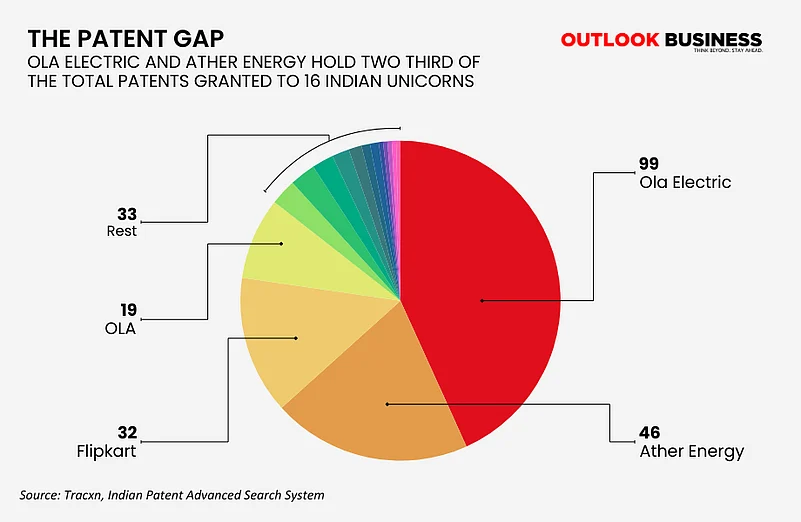

The entire unicorn cohort collectively owns just 229 patents, and 63% of them belong to just two companies—Ola Electric and Ather Energy, according to data from the Indian Patent Advanced Search (IPAS) System.

Ola Electric leads the patent tally with 99 grants, followed by Ather Energy with 46. Together, these two EV startups account for almost two-thirds of all patents held by Indian unicorns.

According to the IPAS data, Ola and Ola Electric—both founded by Bhavish Aggarwal—collectively hold 118 patents.

However, a source familiar with Ola’s operations claimed that the company has applied for over 650 patents, with 180 granted so far. “This includes Ola Electric, Ola Consumer and Krutrim, with the EV company having the biggest chunk of patents at around 70-80%,” the person added.

Ola Electric spent Rs 507 crore in FY23—19.3% of its revenue—up from Rs 175 crore the previous year. It plans to invest another Rs 1,600 crore in R&D between FY25 and FY27. “R&D and technology is at the core of our business model,” the company’s IPO prospectus stated before it went public last year.

Ather Energy, meanwhile, spent Rs 236 crore on R&D in FY24, up from Rs 191 crore in FY23. Its IPO prospectus said that it has plans to deploy Rs 750 crore from its IPO proceeds into further R&D.

Flipkart, notably, is the e-commerce player with the most number of patents at 32.

“Flipkart has over 30 patents issued by India IPO and a few by the US PTO,” a company spokesperson said. “We started a patenting program recognising that we generate enormous intellectual property.”

The company said that it pursues patents across diverse areas—supply chain, warehousing, data science, UX, and more—where innovations solve real-world problems and enhance customer and stakeholder experiences.

On the other end of the spectrum are 101 unicorns with no patents at all—including well-known names like Paytm, PhonePe, Swiggy, Zepto, Zetwerk, Nykaa, boAt, Rapido, Krutrim, Zomato, and Policybazaar.

Union Minister Piyush Goyal didn’t mince words when he called for a “reality check” at Startup Mahakumbh earlier this month. “Indian startups need a reality check in terms of what they are doing. It is essential that we focus on industries that truly add value to our economy. We shouldn’t shy away from competition, but rather strive for innovation and long-term sustainability,” he said.

That criticism sparked a flurry of reactions from founders.

For instance, Zepto founder Aadit Palicha took to LinkedIn after Goyal’s comment to share his perspective: “Any capital we generate from this business… will be invested towards long-term innovation and value creation in India.”

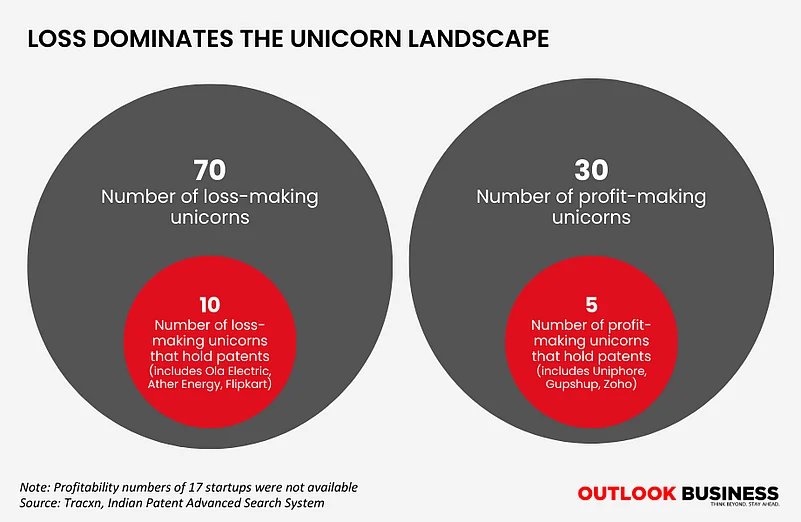

But the bigger issue may be profitability—or the lack thereof. According to Tracxn, just 30 of India’s 117 unicorns are profitable. Among these, only five hold patents. Of the 70 loss-making unicorns, 10 have patents.

Some experts argue that expecting consumer tech firms to file patents may be misguided. “They are building their whole framework on Amazon's or Google’s infrastructure,” said an industry executive. Much of the innovation lies in delivery models or UX—not core technology.

But that argument weakens when compared with global peers. DoorDash, a US food delivery firm, holds 329 patents globally.

A Pipeline Bottleneck

Many Indian unicorns have applied for far more patents than they’ve received. Ola Electric has published 306 patent applications—triple the number granted. Ather has applied for 98; Flipkart, 169. Fractal Analytics has published 12, but only one has been granted.

boAt and Krutrim have each filed a handful of applications, but received none yet.

The reason? India’s patent review system is notoriously sluggish. “Indian IP office is one of the slowest in the world,” said an executive from a startup with multiple pending applications. While new examiners have been hired, a large backlog and training delays persist.

Meanwhile, some unicorns are focusing their IP efforts abroad. AI startup Gupshup, for instance, holds three granted patents—all in the U.S.

“In India, the timeline is longer, and the scrutiny on disclosures is more intensive,” said Nahida Shaikh, Senior Director - Legal, at Gupshup. “The USPTO offers a more streamlined approach with options for expedited examination.”

The ‘Per Se’ Conundrum

Software patents remain a grey area. India does not allow software to be patented unless it demonstrates a clear industrial application. Section 3(k) of the Patent Act, which excludes “computer programs per se,” remains a legal thicket.

Courts have interpreted this differently. The Delhi High Court has ruled that software may be patentable if it improves speed or efficiency. The Madras High Court granted a software patent without establishing any technical advancement.

“The real issue is the inconsistent application of this principle,” said Essenese Obhan, Managing Partner at Obhan & Associates. “That’s why startups often file first in the US, where the rules are clearer.”

Draft CRI (Computer-Related Inventions) guidelines released recently are intended to clarify things—but lawyers say they fall short. One controversial requirement is that applicants disclose all AI training data. “This is impractical,” Obhan said, “especially since training data can be proprietary and massive in volume.”

Beyond regulation and delays, there’s also a knowledge gap.

“Startups need an intellectual property policy,” said Rodney D Ryder, Founding Partner, Scriboard. Many are unaware that a simple IP landscaping exercise could help them understand what’s patentable and what’s already in the public domain.

While India’s patent system is seen as sluggish, Ryder noted that fast-tracking is possible—if founders stay engaged and push their legal teams to act.

“There’s a lot of noise about how we’re doing, but the key is to stay focused on the work,” said one startup founder. “The noise will eventually fade.”

What remains to be seen is whether India’s billion-dollar startups will also become billion-dollar innovators—or continue building billion-dollar valuations on borrowed tech.