When it came to letting go of his eight-year-old diesel variant of Maruti Suzuki’s Brezza, Swadesh Singh thought of buying an electric car. It would not only save on fuel costs but also take care of the ever-changing regulatory norms for internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles in the country. Delhi’s air-pollution combating scheme, Graded Response Action Plan, is especially annoying.

And anyway, his BS IV model had only two years left to ply on the roads of the national capital. With the government schemes incentivising electric vehicles (EVs) and the industry launching more EV models, Singh was optimistic that electric cars would get a bit cheaper in the next couple of years.

However, that did not happen.

Empty Pockets

“The upfront cost is higher than other cars; plus batteries, which are very important in EVs, are not covered in standard car insurance. You have to add a top up. On top of it, many of my friends have complained of poor service vis-a-vis EVs,” says Singh, a professor in one of Delhi University’s colleges.

For people like Singh, the biggest deterrent in shifting from ICE to EVs is the cost factor, which is compounded by the stagnation in middle-class incomes.

According to Marcellus Investment Managers, the average annual income for this group has grown at a mere 0.4% compound annual growth rate over the past decade, from ₹10.2 lakh to ₹10.7 lakh, while car prices have risen 7.6% annually between 2019 and 2024, according to Jato Dynamics, an automotive business-intelligence firm. Inflation, averaging 5% annually, has further squeezed purchasing power.

“Inflation may have gone down for the past few quarters but real wage growth has been flattish,” says Rajani Sinha, chief economist at credit-rating agency CareEdge Group.

The transition to electric powertrain in the country has been a mixed bag so far. In 2024–25, over 57% of the three-wheelers sold in India were EVs, staying on top in terms of EV adoption across the vehicle categories.

Similarly, the electric two-wheeler industry crossed the 1mn sales mark in 2024–25 for the first time, leading the charge in terms of sales volume.

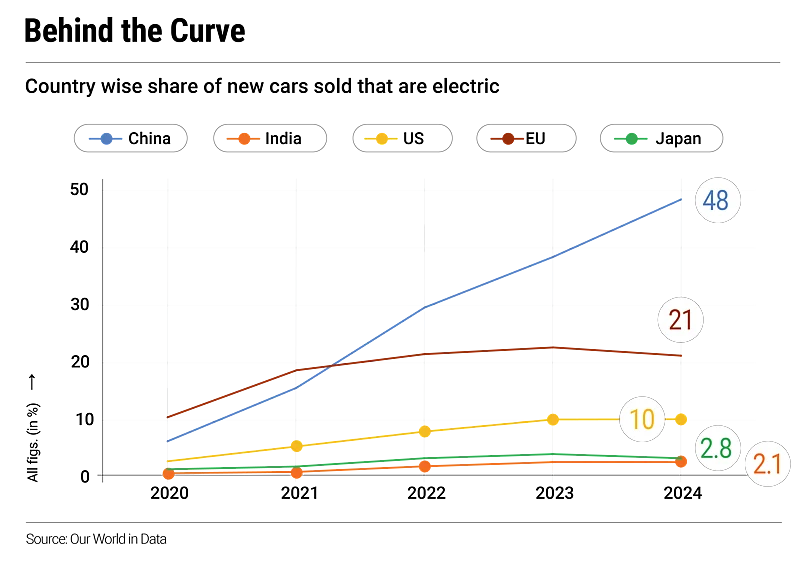

On the contrary, one segment which has lagged on both share and volume is passenger vehicles (PVs). Out of over 4.1mn PVs sold in 2024–25, about 100,000 were electric. This translates to a sales share of about 2.5%, only marginally higher than the 2.3% share in 2023–24.

“India is doing well with electric two-wheelers and electric three-wheelers. With regard to…electric cars it has been slow,” said a recently released Niti Aayog report on the country’s adoption of EVs in the past 10 years.

Handbrake On

High cost has been a roadblock in the mass adoption of EVs. While the cost difference has gone down in the past three years as battery prices eased and stricter emission norms were clamped on ICE vehicles, the difference continues to be high, say experts.

MG Motor’s Windsor EV, the car Singh was looking to buy, became pricier by ₹50,000 in January this year.

The price gap between the electric and ICE variants of say Tata Motors’ Nexon has so far ranged between 10% and 15%. Under the new GST regime, this gap could widen to as much as 30%, according to Tarpan Vyas, founder and CEO of EVINDIA, a platform dedicated to EVs. “The difference appears even starker because the entry-level EV variant offers features comparable to the mid-level ICE variant,” he adds.

Out of over 4.1mn passenger vehicles sold in 2024–25, about 100,000 were electric...a sales share of about 2.5%, only marginally higher than the 2.3% share in 2023–24

Additional charges such as insurance for batteries can further increase the ownership cost by around 1-3%, which may turn out to be a deal-breaker for many like Singh.

Cost parity of an EV comes only after considering benefits given by central and state governments, said a report by Kotak Mutual Fund. “Viability of an EV on like-to-like basis with ICE vehicle is yet evolving,” it said.

EVs are expensive to produce as the Indian auto industry is dependent on imported technology for crucial components like batteries and traction motors.

“For any automobile company, the component infrastructure is an exceedingly important aspect. You take the battery. There is no company yet manufacturing batteries in India at a competitive price. Most of the internal parts [of an EV] are also imported. The result is that all electric cars in India become high priced,” RC Bhargava, Maruti Suzuki chairman, had said a few months back.

Fewer Takers

A typical compact ICE car contains imported components worth ₹1–1.25 lakh, an auto analyst explains. On the other hand, this figure jumps to about ₹2.8–3.5 lakh in small electric cars even when only battery cells and traction motors are considered.

“We have given the pricing power to the outsiders,” says an analyst. Even when a component is produced locally after partnership with foreign players, the Indian partner needs to pay royalty to the foreign firm. While some part of this cost is transferred to the consumer, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) also take a hit on their margins.

Most OEMs are still recording lower profitability or losses selling EVs. Among the EV makers in India, only Tata Motors has so far been able to achieve operational profitability for the first time in 2024–25.

Some experts suggest that is also the reason behind a lack of options in the affordable electric-car segment.

There are currently three electric cars priced below ₹10 lakh. These include MG Comet EV, Tata Punch EV and Tata Tiago EV. Data shows that the ICE variants of these models are still far ahead in sales numbers than the electric ones. In 2024–25, about 18,000 units of Punch’s EV variant were sold in comparison to over 100,000 units of petrol and over 71,000 units of CNG variants.

The same trend is seen for Tiago which recorded sales of 17,145 units compared to 36,302 units of petrol variant and 15,775 units of CNG variant.

“Whatever the options customers have in the affordable car segment, particularly in electric drive train, are the base variants which the customers do not want. The better equipped options breach the ₹10-lakh mark,” says Vilas Deshpande, chief operating officer, Vayve Mobility, an EV manufacturer.

Second Set of Wheels

With the affordable car segment already on a decline, OEMs are reluctant to invest in low-margin EVs. “Automakers do not want to put money into smaller EVs, particularly when the technology is new and more expensive,” says another analyst.

Even buyers of higher-end EVs often keep an ICE vehicle as a backup for times when their EV is unavailable. Those who rely solely on an EV often risk facing challenges like Ghaziabad-based Bharat Bhushan, 49, a consultant with a media firm.

His BYD E6 ended up at the service centre after a technical glitch showed up on July 9, when heavy rains flooded several parts of the National Capital Region (NCR). Vehicle inspection revealed that water caused the malfunction and the ₹15-lakh battery would need to be replaced.

The car dealer took over a month to change the battery and Bhushan was left with no other option but book a cab to commute to Delhi.

“After inspecting the car twice in the last one month, the insurance company has now agreed to cover the battery claim,” Bhushan says, claiming that hundreds of EVs owners faced similar issues during recent waterlogging in NCR.

The insurance company did not respond even after repeated attempts by Outlook Business.

Currently, EVs are being projected as a premium vehicle. Experts say only 30–40% EV owners are first-time buyers while the rest have an ICE vehicle that they use for long-distance travel.

The Indian market’s exposure to EV technology is in its initial phase, says Kedar Balasubramanian, cofounder of PerspectiEV Club, an independent energy platform. “Every technology has an adoption curve. Initially the early adopters are followed by mass adopters and then the late adopters. Early adopters are those who either know the technology or have the purchasing power,” he says.

Still a Dream

Owning a car has long been an aspiration of the Indian middle class since the time of liberalisation. According to a 2021 survey by People Research on India’s Consumer Economy, a research centre, that defined the middle class as households earning in the range of ₹5–30 lakh annually, nearly 58% of all cars in the country are owned by the middle class, compared to just 23% by the rich.

To make the EV technology accessible to the masses, the government has been generous in providing support to the industry. It has got back-to-back subsidies, production-linked incentives for manufacturers, direct tax incentives for buyers along with a concessional 5% GST (compared to 18% or 40% on hybrids) and investments worth thousands of crores by manufacturers.

Listing the ₹8,000-crore Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid and) Electric Vehicles—FAME—in India Phase II scheme for buying EVs at a subsidised price and improving the charging infrastructure, Prime Minister Narendra Modi in January this year had highlighted the importance of the EV industry for the government in achieving its net-zero targets.

“The government is constantly taking policy decisions and supporting the industry to expand electric mobility in the country. Through this [FAME], more than 1.6mn EVs got the support. In our third term, we have brought in the PM Edrive scheme,” he had said.

But for many, an EV is not part of the middle-class dream. This Diwali, Swadesh Singh is now planning to buy a hybrid car which will not only save fuel consumption but also avoid the risks associated with an EV.