India plans a ₹7350 crore scheme to promote domestic manufacturing of rare-earth permanent magnets.

Five integrated units will be supported with sales-linked incentives and capital subsidies.

Finance Ministry flags over-reliance on subsidies and the lack of a long-term critical minerals strategy.

The government is in the last stage of launching a massive ₹7,350 crore scheme to boost the domestic production of rare-earth permanent magnets, which India has been highly dependent on China for sourcing.

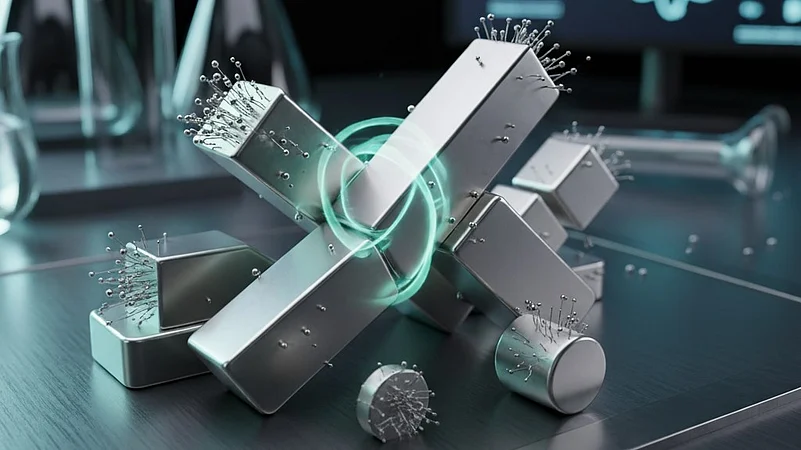

The scheme is likely to be called the Scheme to Promote Sintered Rare Earth Permanent Magnet Manufacturing in India and aims to develop a fully indigenous manufacturing ecosystem with an estimated annual capacity of up to 6,000 tonnes.

The scheme has an objective to build a domestic value chain spanning the conversion of neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) oxide into sintered neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, which are critical to the automobile, electronics, defence, and the energy sectors. The rare-earth permanent magnets production involves mining, beneficiation, processing, extraction, refining to earth oxide, conversion to metal and alloy, and magnet manufacturing.

The proposed scheme will provide incentives to facilities capable of undertaking the final stages, which are conversion of rare-earth to metal, metal to alloy, and alloy to magnet, according to Business Standard. However, a challenging point is that India currently lacks the cutting-edge technology needed for rare earth elements extraction and the infrastructure to manage these processes.

Atmanirbhar: Powered by Rare-Earths

Under the scheme, the government will support setting up five integrated rare-earth permanent magnet manufacturing units with a capacity of up to 1,200 tonnes per annum each. Applicants may bid for a minimum of 600 tonnes per annum and a maximum of 1,200 tonnes per annum in 10 tonnes per annum increments. Selected firms will then be eligible for financial support in two ways: first, a sales-linked incentive on the sale of sintered neodymium-iron-boron magnets; second, a capital subsidy for establishing integrated neodymium-iron-boron manufacturing units in India.

The upcoming schemes include a gestation period of two years for setting up facilities and beginning production. Production is expected to gradually ramp up between three to seven years to achieve the target of 6,000 tonnes per annum.

Who Gets To Build India’s Rare-Earth Ecosystem?

The Ministry of Heavy Industries will issue a Request for Proposal through a Global Tender Enquiry to invite bids for five integrated sintered rare-earth permanent magnet manufacturing facilities. The selection process will follow a transparent Least Cost System involving both technical and financial bids. Only applicants who qualify in the technical evaluation will have their financial bids opened.

During the financial bid stage, applicants must specify the per-kilogram sales incentive they seek, capped at ₹2,150 per kilogram of sintered neodymium-iron-boron magnets.

Indian Rare Earths Limited (IREL) currently produces around 500 tonnes of neodymium-praseodymium oxide annually, sufficient for approximately 1,500 tonnes of sintered rare-earth permanent magnets. Under the scheme, IREL will supply 200 tonnes per annum to the applicant with the lowest incentive bid, 167 tonnes per annum to the second-lowest bidder, and 133 tonnes per annum to the third.

The remaining quantities will need to be sourced independently by the companies. The last two applicants with the lowest bids will have to arrange their entire requirement of 400 tonnes per annum on their own, without any supply from IREL.

The Ministry of Heavy Industries will oversee the scheme’s implementation through an inter-ministerial Scheme Monitoring Committee, headed by the MHI Secretary.

Finance Ministry Raises Red Flags in the Scheme

The Department of Expenditure (DoE), under the Union Ministry of Finance, has raised several questions on the Ministry of Heavy Industry’s rare-earth production boost scheme while highlighting that the scheme could leave India dependent on rare-earth oxides from elsewhere other than China, and the generous subsidies could in turn leave only little incentives for the bidders to improve efficiency or cut costs. The department also raised questions on why a separate scheme was needed instead of leveraging the broader National Critical Mineral Mission, Business Standard reported.

The DoE has also sought clarity on the long-term strategy on securing critical minerals, as the proposed scheme is limited to setting up plants that convert rare-earth oxides into permanent magnets. The DoE also noted that while the production-linked incentive aims to boost domestic production and limit over-dependency on imports, the scheme could encourage reliance on subsidies rather than competitiveness.

The Reliance Dilemma: Production or Innovation?

China recently tightened its grip on exports of rare-earth processing technology apart from earlier curbs placed on the export of rare earth materials. It has also sought assurances from India regarding not re-exporting rare earths. While China has resumed exports of rare-earth products to several countries in Southeast Asia and the European Union, vendors supplying India have yet to receive approval from Chinese authorities. China maintains a near-monopoly on rare-earth production and has weaponised this dominance as leverage in its trade war with the US. Indian manufacturers, especially in the automobile and electric vehicle industries, are rattled by rising uncertainty and supply-chain disruptions.

India currently imports nearly all of its rare-earth permanent magnets, with government estimates projecting domestic demand to double to 8,200 tonnes per year by 2030, up from the current 4,010 tonnes. Moreover, finished rare-earth permanent magnets cost nearly 43% more domestically than abroad, according to reports.

While the scheme marks a critical step toward limiting our dependency on China and building a self-reliant rare-earth ecosystem, it also presents an important dilemma for India and the industry. With nearly 30% of the global EV market expected to shift to rare-earth-free motors by 2035 and increasing research into alternative magnet technologies, the question is not just whether India needs a production boost; it is whether this boost will be complemented by robust investment in R&D.

Striking the right balance between production and innovation is the sweet spot for India’s path toward Vikasit Bharat by 2047.