Devendra Fadnavis has returned as Maharashtra chief minister after his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won 132 out of the 149 seats it contested, and its Mahayuti coalition, won a thumping 235 out of 286 seats. While the reasons for specific electoral outcomes are varied and disparate, one reason that everyone seems to agree on is the popularity of the Ladki Bahin scheme.

Launched in July this year, following the humbling general election results, the scheme promises to give Rs 1,500 every month to women applicants along with three free liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) cylinders and educational support.

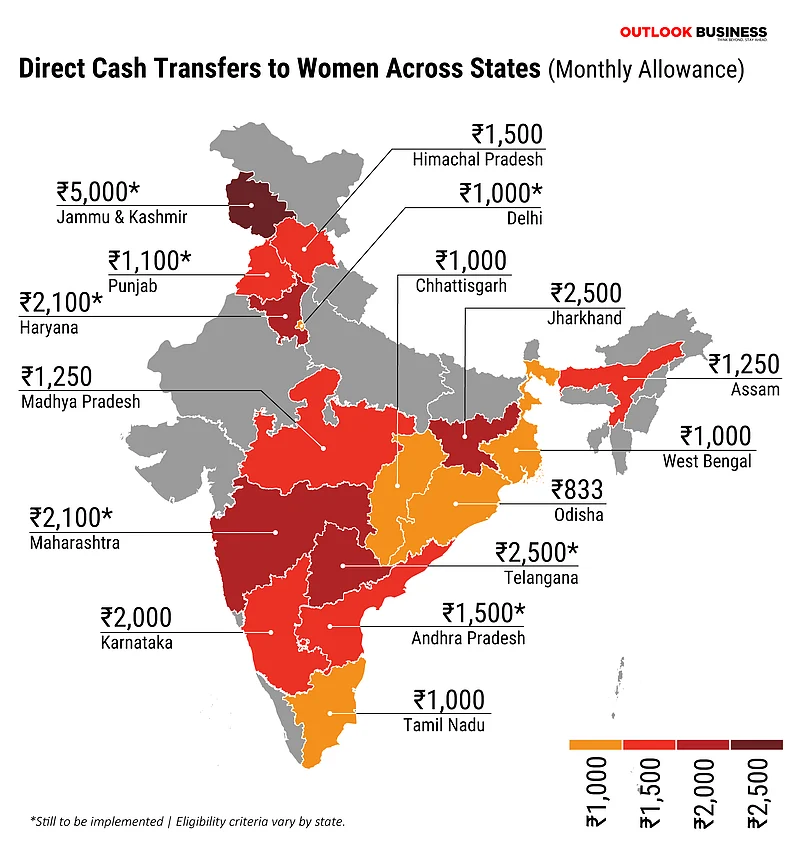

Similar schemes have been launched by state governments across the country and political parties seem to have realised that direct cash transfers to women is an effective way to secure women’s votes.

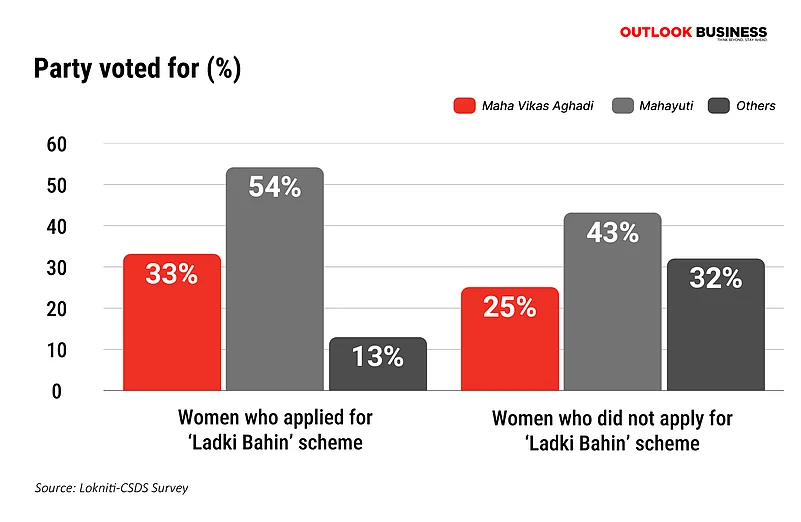

According to a Lokniti-Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) survey, more than half of the beneficiaries of Ladki Bahin scheme voted for Mahayuti, the coalition made up of BJP, the Eknath Shinde-led Shiv Sena (SHS) and the Ajit Pawar-led Nationalist Congress Party (NCP). Against them, the Maha Vikas Aghadi, comprising Congress, Shiv Sena (Uddhav Balasaheb Thackeray) and NCP (Sharad Pawar) fell tremendously short.

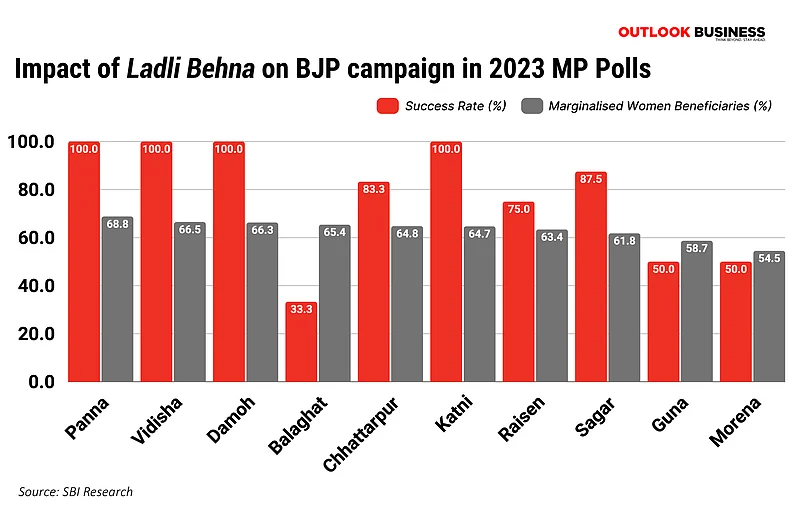

A similar trend was noticed in Madhya Pradesh when the state voted earlier this year. Districts with a high number of beneficiaries of the direct cash transfer scheme Ladli Behna voted in disproportionately high numbers for the incumbent BJP. The scheme offers Rs 1,000 cash assistance to women.

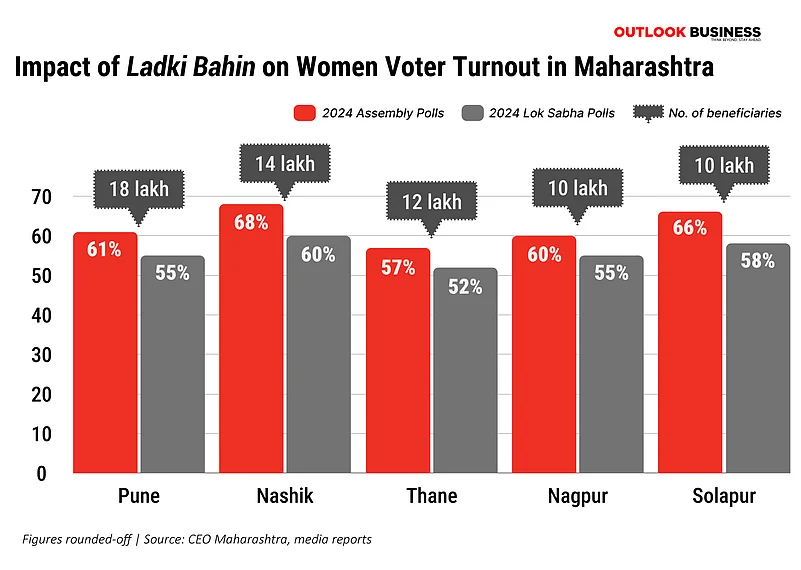

The link between direct cash transfer schemes and electoral success is further validated by increased voter turnout among women. For example, in the Maharashtra elections, districts with the higher number of beneficiaries of the Ladki Bahin scheme also saw a significant increase in voter turnout among women.

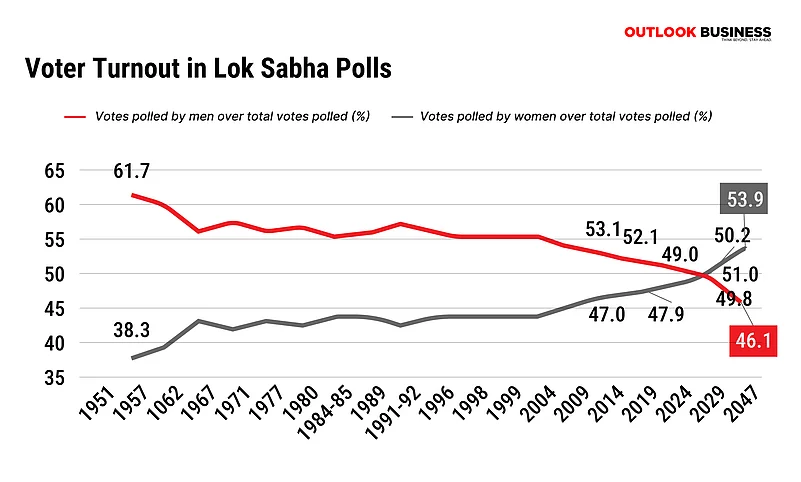

In fact, one can see a significant difference in the turnout among women voters in the Lok Sabha elections earlier this year and the assembly elections that took place after the launch of the Ladki Bahin scheme.

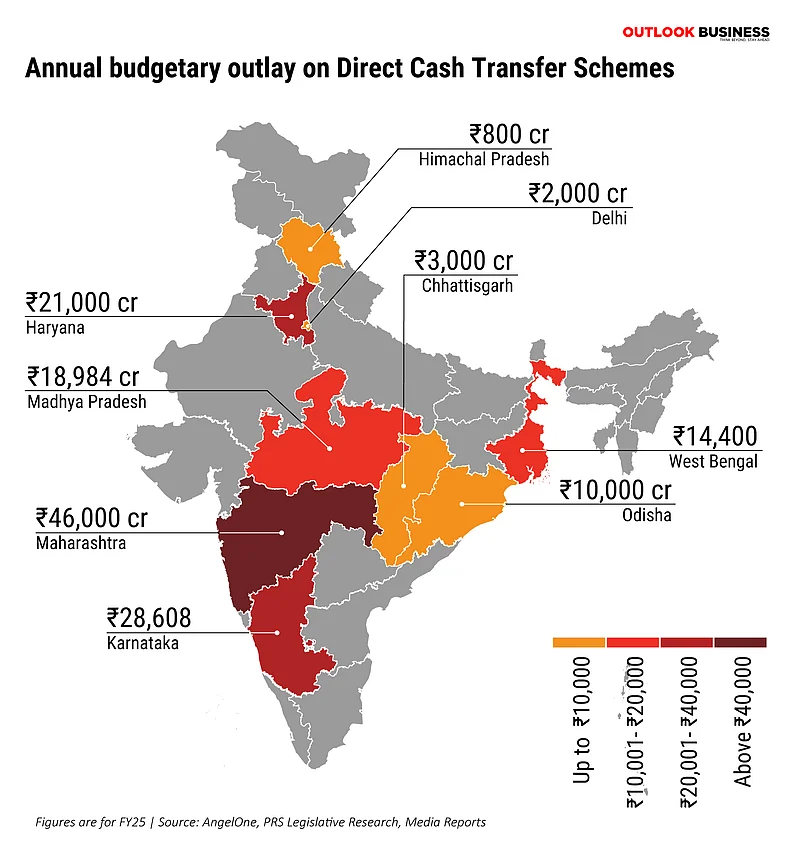

Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh are not the only two states to have implemented direct cash transfers. Such schemes have either been implemented in 16 out of 28 Indian states. Here is how much each state is paying its women citizens.

Why are incumbent political parties spending so lavishly on such schemes? One of the reasons for that is the rise of women as a distinct political bloc with specific demands, aspirations and causes.

More and more women are coming out to vote. Of the 55 crore votes cast in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, 26 crore (47.9 per cent) came from women. In 2024, women accounted for 31.2 crore out of 64.2 crore votes cast, 48.6 per cent. At this pace, the number of women voters in India could reach 37 crore by 2029, surpassing the number of male voters, 36 crore, according to a study by SBI Research, the research arm of the State Bank of India.

Notably, women voter turnout was higher than men in 19 out of India’s 36 political units (28 states and 8 Union Territories) in the 2024 general elections.

And as a consequence of that, political parties have decided to splurge on direct cash transfers to women. These direct cash transfers currently cost over Rs 2 lakh annually, making up 3–11 per cent of state revenues, according to SBI Research. About a fifth of India’s adult women are beneficiaries of one or the other cash transfer scheme, according to a report by Axis Bank.

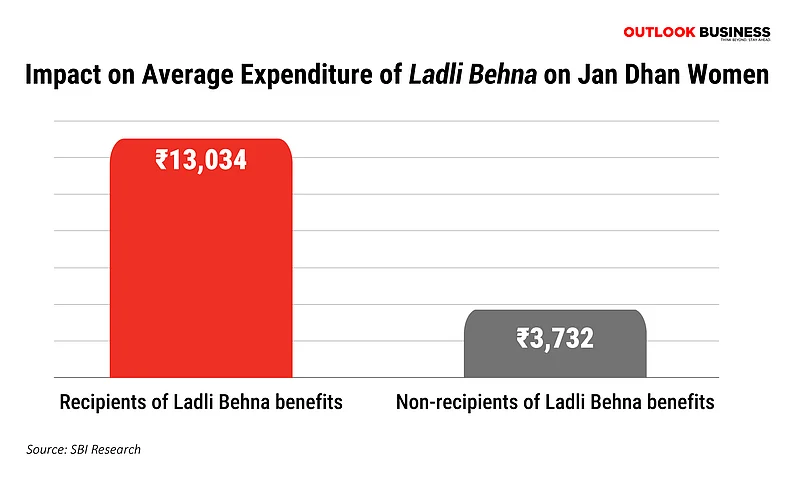

While these schemes are expensive, they seem to have had a significant impact on women’s spending power.

To assess the impact of Madhya Pradesh’s Ladli Behna scheme, SBI Research compared women who received these cash transfers in their Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) bank accounts against those who did not.

The comparison, using the difference-in-differences (DiD) estimation method, revealed that beneficiaries of cash transfers spent approximately Rs 9,302 more at merchant outlets than non-beneficiaries, SBI Research found. It also found that while non-beneficiaries spent mainly on essentials, beneficiaries allocated more to consumer goods.

Beyond cash transfers, women voters are also having a say on critical policy decisions for the past few years. Bihar’s decision to ban alcohol in the state in 2015, and thus give up a large source of revenue, was a bid to placate women who had been seeking such a ban for years.

Successive Narendra Modi-led governments have made cooking fuel and women’s education-related schemes political planks. That has forced opposition parties to frame or propose similar policies. The Indian woman voter is certainly not a monolith. Voters’ concerns depend on economic status, culture, socio-political values and location. But for the first time in India’s history, women wield so much power as a political bloc. How they vote will decide India’s journey.