In late 2021, Barbados, a small island country in the Caribbean, became the first one in the world to announce that it was planning to set up its embassy on Decentraland, a popular metaverse platform. This embassy will enable citizens to get consular services virtually, while the country is also working on deals with other metaverse projects. Around the same time, South Korea’s capital Seoul announced its plan to establish a “Metaverse Seoul”, a full-service virtual world, by 2026, making it the first city government in the world to enter the space.

What Barbados and Seoul have done is just the beginning. The rapid growth of technology has made way for new innovations in a world that is exploring the age of metaverse with connected and persistent virtual realities, where we will live digital lives alongside our real ones.

With the two worlds set to collide, a question mark hangs over how the real-world ideas of nation-state, law, regulation and policies will mingle with the idea of metaverse, as the two sets seem contradictory in nature. Experts argue that the very conceptualisation of metaverse is open and unregulated in nature. The budding virtual world is being designed in a way that makes it a boundless, borderless place, where technology and culture intersect to create a user-owned world. That, however, is not how a nation-state, with a central government authority, functions.

Meta Clones of Nations

As a user-governed world, metaverse offers a possibility where creators share the same level of influence as governments do in the real world. “This is perhaps the most intriguing aspect of blockchain-based virtual worlds—digital worlds created as nations by users that are governed by a community of believers who assert their influence based on the voting power they hold—basically the number of tokens they hold,” says Ankit Gaur, CEO and co-founder, EasyFi Network, a company that builds metaverse platforms.

Once nation-states increase their stake in metaverse, things could change. The key, as Sharat Chandra, vice president of research and strategy at EarthID, a Web 3-focussed organisation, mentions, lies with the telecommunication networks and cloud service providers, which are gateways to the metaverse world. In this respect, the governments will hold sway. “Governments would be able to exercise control over these channels effectively to ensure compliance. Forward-looking countries, like South Korea, have laid a metaverse roadmap and are creating an ecosystem of developers and technologists to foster innovation and augment the potential of meta-commerce,” says Chandra.

Many sovereign governments have expressed a desire to take part in the development of a digital twin of their country’s physical world, says Gaur. These are going to be the digital twins of a country administered by a sovereign government—democratically elected or otherwise. “If technology permits and evolves, we could have true-to-the-ground copies of the entire country down to the street, very much like an interactable Google Street view,” he says.

Experts believe that these governments on the metaverse, which could be used for imparting policies on social, political and fiscal issues and processes towards social welfare, will essentially be driven by a centrally controlled government entity. While this kind of metaverse will have several uses, it will have a geographical boundary for all the citizens on the nation-state metaverse and will be highly regulated by local laws. “Users will have the liberty to walk into the metaverse, use a service offered by the government entities like any free-nation person could do in the real-world. The limitations would be that of movement between two adjacent sovereign countries in a larger metaverse,” says Gaur.

Travelling in Metaverse

If metaverse companies are sanctioned to make adversarial countries on their platform, how would the visa issue play out against the backdrop of real-world vagaries? Will people even need a visa or a pass to cross boundaries in the metaverse?

In a normal metaverse, one needs to have an avatar non-fungible token to enter and explore, which acts like a login instrument or a digital passport. Industry experts, however, say that in case a specific metaverse belongs to a sovereign country, there has to be a digital visa for entering or exiting. The nations building their metaverses will have to figure this out with the help of technology.

“Maybe blockchain is the answer, but there have to be other mechanisms that make for better solutions which are yet to be found. The future might even see virtual embassies in these country metaverses. These embassies could provide visas to enter a country’s metaverse or help their own citizens in other metaverses,” says Gaur.

However, some experts point out that if a private company is building the metaverse comprising two countries, that may become a cohesive open unit, where the boundaries of the company operate and not the boundaries of individual countries. In such cases, the permits may be needed to move from the metaverse of one company to the one held by another and digital visas become redundant.

Seeing the future of metaverse, Alok Joshi, co-founder, Lepasa, a platform which is building a metaverse ecosystem, says that the metaverse opportunity is so humongous that it is not even possible to estimate its addressable size in the future. “Most of the leading financial institutions around the globe, like the Citi Group, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan, etc., are looking at it as the next generation of the internet, and its total addressable market size is as big as five billion users [which is the total number of the internet users in the world]. CitiBank predicts that the metaverse could be a $13-trillion opportunity by 2030,” says Joshi.

With such numbers, dealing with data in the metaverse, in general, would be another pain point. Computing infrastructure, coupled with high-speed low-latency networks, would be needed to ensure enterprises are equipped adequately to store and process massive amounts of data generated within the metaverse. “Metaverse will collect an exponential amount of data as compared to today’s internet, including data capturing expressions, behaviour, motions and emotions. Securing such huge data will become critical,” says Purushottam Anand, founder, Crypto Legal.

Chandra points out that global data regulations, like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, need to be enforced aggressively to ensure citizens’ data rights are protected. Anand and Chandra’s concerns suggest that metaverse will not be able to fully escape national or international regulations.

Regulation Rigmarole

Metaverse platforms are mostly being built by decentralised organisations or platforms which are not headed or established by identifiable individuals. Unlike a nation which is governed by a constitutional scheme, the idea of metaverse is not a structured jurisprudence. “Decentralised platforms are being developed by communities of many anonymous/pseudonymous persons. For example, if any investor or customer suffers any loss/harm due to some problem in the Ethereum or Decentraland network, it is not clear which person(s) or organisation can be held responsible for such loss,” says Anand, who is also a lawyer.

The metaverse offers an immersive experience using augmented reality and virtual reality, which could make it difficult for users to distinguish between virtual experience from reality. “Bullying or assault in the metaverse is, therefore, likely to have a higher, more severe psychological impact on individuals. Until a robust KYC and identification mechanism is implemented, it will be difficult to trace, identify and initiate any legal action against such perpetrators,” he says.

Many decisions regarding the space are taken by the Web3 metaverse project token holders who hold the right to vote for any decision making, including regulations. “In some scenarios, decentralised autonomous organisations play an important role in deciding the rules and regulations/policies of any metaverse projects. Such decisions are eventually being made by the representatives of the governing community for the whole community. That is the biggest reason why communities prefer the decentralised and open metaverse infrastructure over the ones like Meta, which is fully governed by a centralised entity,” says Lokesh Rao, co-founder and CEO, Trace Network Labs.

“For all the companies dealing in the Web3 metaverse to establish a shared code of conduct, it involves setting trust and safety policies to avoid doxxing or spying. A community should be authorised to enforce these policies,” says Rao, adding that metaverse is still in a developing stage, which means that several improvements will be required from time to time to build a secure space for all.

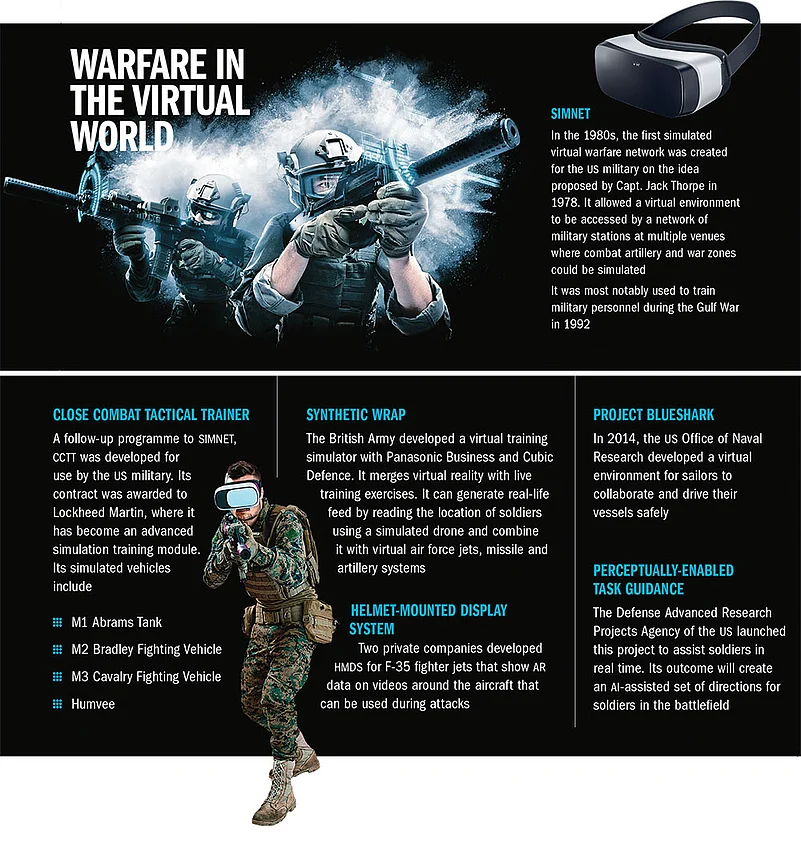

While the borders of metaverse get drawn and redrawn, its use cases within a nation-state by governments are increasing rapidly. Case in point: The defence sector. VR has even been listed as one of the most important technologies of the 21st century by the US Department of Defense. The Advanced Information Technology division of the US Naval Research Laboratory in collaboration with Columbia University has even been developing the Battlefield Augmented Reality System for armed forces in combat operations.

Investing in a Digital Future

India’s commitment to digitisation of defence is reflected in the fact that the government has set up a Defence AI Project Agency chaired by the secretary (defence production) and has allocated Rs 100 crore annually for AI-enabled projects. Additionally, the Defence Research and Development Organisation has the Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics, a premier laboratory involved in research and development in the areas of AI, robotics, command and control, information and communication security leading to the development of critical products for battlefield, secure communication and information management systems.

While the metaverse is the future of warfare, armed forces, especially, are rigid in their thought processes, says Retired Lt General Vinod Bhatia, adding that most of the time, the present relevance of technology takes up focus and resource and then the catch up game follows.

“It would not be wise to assume that everything can be done in-house. There is more in the civil domain and we need to get the experts in the civil domain on board and let them design the technology in the Indian context,” he opines.

“We are late starters as far as technology is concerned but we can still take a late-mover advantage,” Bhatia adds.

With input from Kamalika Ghosh