- I owe my success to The value my parents placed on education

- Sounding board My wife

- My strongest belief There is no substitute for hard work

- Most inspiring phrase Be what you want to see

- Best advice I ever got Be what you are but never stop learning

- Best friends The Detroit Gang

- Inspiration People who have made a difference to the life of others

- Most important decision To move back to India

- Most touching moment A mail my son wrote to me on my promotio

- The day I felt really low That drive from Nashik to Tata Memorial, Mumbai

- Peaceful moments Listening to Bhajans

- Bliss Family holidays

- Greatest gratification Values my children have

- Advice to my kids Time is precious. Don’t waste it away

- Biggest regret Not excelling in any skill outside my profession

- My dream now To see Mahindra become a respected global brand

- Eternal quest Perfection

***

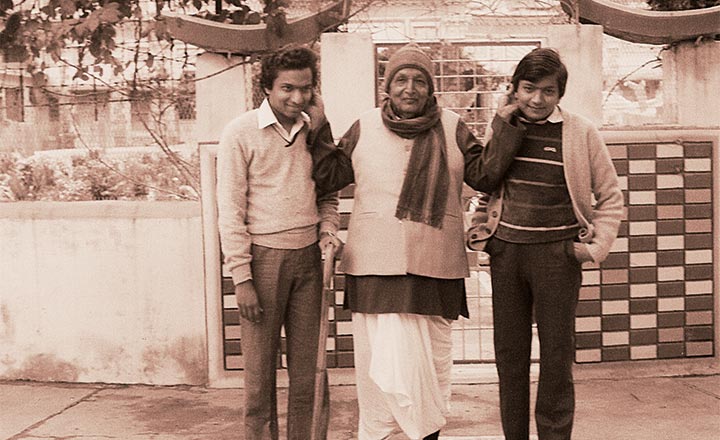

Even today, I am filled with nostalgia when I think of our home in Harpalpur, the house that I was born in and I am told the Maharaja of the region had gifted to my great grandfather, fondly known as Malik saheb. In that small village in Madhya Pradesh, everybody knew each other. Malik saheb was an honourable man. He cared for the villagers , and so was referred to as grandfather (I called him Bapuji). Malik saheb didn’t cheat the buyers nor did he squeeze the sellers, even though he was a trader; it’s not surprising he earned respect that outlived him. I stayed with Bapuji in Harpalpur until I was seven-years-old. My younger brother, Suresh replaced me in Harpalpur when I went to live with my father (Papa) and mother in the big city. My parents didn’t have the resources but somehow they managed to get almost everything we wanted. All my growing years, there used to be this disquiet during the last few days of the month, which, I realised only later, was because my parents had run out of money. But we never felt like we missed out on anything and that humble beginning set the foundation of our values and our life.

Fortunately for my parents, all of us turned out to be studious without anyone prodding us, although Papa and Ma did push us subtly. All of us brothers went to a relatively unknown school, Shree Jain Vidyalay in Calcutta, and stood first in class every single year. It was a year of sadness in our home when in grade seven, I came second in the class. We all got tuition waivers all through. Some of those lessons are still fresh in my memory. Once Ojha sir slapped me and I didn’t speak with him for two weeks — he was a great maths teacher and I knew I was his favourite student but he had been unfair that day, I felt. No one in class could answer his question; he didn’t say a word to the others, but he slapped me. Two weeks later, I asked him why he picked on me and he said, “I didn’t expect them to know, but I expected you to have the answer.” That day I learnt there is no point comparing yourself with anyone because everyone has a certain threshold and you are only expected to perform to your potential.

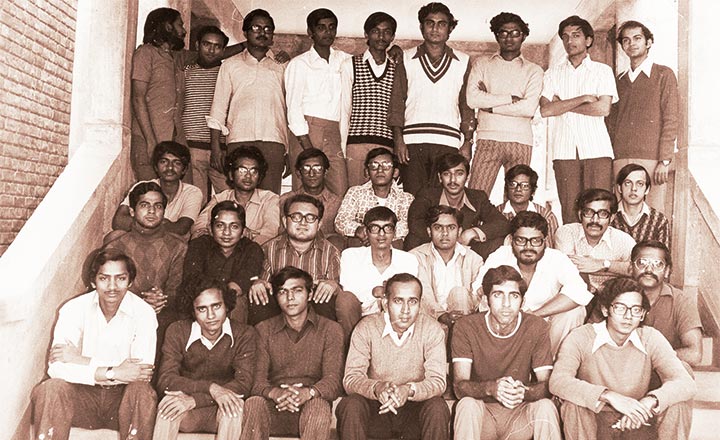

My life was shaped by a series of uncanny coincidences. I landed in IIT not by design but because I goofed up on the entrance exam dates for Bengal Engineering College, which we preferred over IIT since it was closer to home. My rank was exactly 900, which was the last rank qualifying for mechanical engineering in IIT Kanpur and I still remember the coordinator did not want to give me that seat wanting to wait for a “smarter” candidate. Things seemed to be conspiring against me — I didn’t clear the medical test. I weighed 33 kg against a minimum requirement of 41 kg and my chest was 22 inches wide as against the required 24 inches. I was also terribly nervous during the interview, which gave the medical examiner one more reason to reject me — my heartbeat was too fast. I was told to get a medical certificate from a doctor at a government hospital, stating that I had no heart problem. We managed to get the certificate with our family doctor’s help and finally, I was through.

Day one in IIT was an unforgettable one. A senior asked me, “When did you get here?” and my reply, “I came tomorrow” made them roar with laughter, setting my stomach churning. I knew no better — in Hindi, kal means yesterday as well as tomorrow. Having studied in Hindi medium institutes all my life, the IIT entrance was the first exam I ever wrote in English. Even in that, I could not have cracked the paper had I not accidently sneaked a peek at the diagram made by the guy sitting diagonally opposite me during the Physics paper — I struggled just to understand the questions through most of the paper.

The first few days were a nightmare. I could not comprehend a word of what was going on in class. On the first day, I found myself in this large hall, L7, where an American professor, Dr Devenport, was delivering a lecture on Chemistry, not my favourite subject anyway. Obviously, I did not follow a single word he said. An Indian professor teaching Maths in English was still bearable, on the other hand, an American accent? No way. I desperately wanted to go back home. But I told myself every moment that I had to do this, that going back home was not an option.

It wasn’t an easy transition at all — you came with all kinds of notions about yourself being a topper and there everyone around you was a topper. The counsellor had reminded us that we were all top rankers but going forward we would all have a lot more to prove; she warned us not to get intimidated or demotivated. That talk did help bring everyone to ground level but I had a double whammy because of my language issue. The English teacher, Mrs. Tharu, was helpful – she created quite a stir the day she supposedly brought an issue of Playboy to class, just for the heck of it. I was not in that class.

By some miracle, I cleared the first semester with a GPA of 8.6. Thereafter, between the mess committee, cultural committee and election campaigns, I still managed to improve my grades every semester. Of course, it helped to have influential friends. I remember the Sri Lankan student who somehow managed to get hold of the question paper of TA102 the night before the exam but was so unprepared, he had no option but to share it with us. Ironically, he still scored a D while I ended up with an A grade — there are no short cuts!

In my final year I got hooked on to the card game, bridge. Half my waking hours in the final year were spent playing bridge. I realised only much later how much the game had sharpened my thinking and memorising abilities, and so effortlessly.

At graduation, Telco rejected me in the interview because I had a high CGPA. They categorically said, we had to call you for the interview because you had high grades but we need to reject you for the same reason because, in our experience, such candidates do not join us — they fly away for further studies to the US. He was right.

Cornell came through after a strange turn of circumstances. But for the postal delay, I wonder where I would have been! A month after my pre-application I had not received any response from Cornell, so I sent in a second pre-application. Replies to both came in days later — the response to the first one was a rejection; the second said, come, apply! Life was truly being dictated by randomness.

Papa could not afford to pay for even my flight tickets, but he got a charitable trust to fund it. His employer, Mr. Kanoi, gave me his old suit, saying I could alter it and wear it. I never wore that suit, but it remained with me the entire time I lived in the US, to remind me of my humble beginning.

***

I landed in the US with only a six-page bulletin on the university. I knew nothing else. My first shock was at the bus station in New York City, when I tried to get a ticket to Ithaca, where Cornell is. I asked for a ticket to “EETHAAKA” in a very heavy Indian accent and the man simply shrugged his shoulders. “Sorry; no such place.” He saw I was anxious and asked me to write it down and then, of course… “Oh! Ithaca, New York, you mean?” My second heart attack was on reaching Ithaca. I stepped out from the cab I had hailed at the bus stop and the cabbie said, “That will be dollar 40, sir.” I wondered, $40 for such a short distance? I don’t think I had even $14 in my pocket then. I said, “Sorry, I don’t have it.” He freaked out. “You mean you don’t have $1 and 40 cents?” I hurriedly pulled out my wallet, counted the cents carefully and handed him the dollar and 40 cents.

110, Cook Street, Ithaca, New York, was lovely. Ram, Pravin, Aspi and I cooked the best meals. Being budding engineers, we believed in assembly line production — my job was to make chapatis. We were there for two years. Oh, how frugally we lived! We shared rooms; cooked every day, washed utensils and clothes by hand, even cut each other's hair, but it was all great fun. The dorm I moved to, the Cascadilla Hall thereafter was great fun too. I made several non-Indian friends, Alan, Phil, Bret, Jo Ellen, Amy, Harsha.

Getting used to complete strangers and a different culture wasn’t easy at all. How hesitant I was to pick up stuff at the supermarket in the initial days! Always afraid someone would chide me for doing so. And who knew what a downtown was? Our college was on a hill and downtown was literally downtown. I was so naïve, I thought downtown was called so because it was down the hill; it was only after visiting a few places that I realised that downtown had nothing to do with downhill or uphill.

Language continued to be my pain point — no one could understand me in the US. My poor TOEFL score turned out to be a blessing in disguise; rather than a teaching assistantship, I landed a research assistantship — I was thrilled!. I will be eternally thankful to professor Jack Booker. He understood that I faced problems because of both — my language and my background. He generously helped me to settle down at Cornell and learn the American way of life. He was a great mechanical engineering professor, and I was lucky to have him as my thesis advisor and a guide all throughout my stint on campus. Later after my Masters, when I secured admission at Stanford’s PhD programme, professor Booker dissuaded me from taking it up – at Cornell, I needed to put in just one more year to get the PhD; Stanford would have put me through the grind for another four years. That gave me a clear three-year lead over my peers.

There were so many things I learnt. In one of the tests, I answered the asked question correctly, but went beyond and got that part wrong. The professor didn’t even give me marks for answering correctly the question that was asked. I was upset and asked him, “Why did you deduct my marks; this was not even a part of the question?” He said, “It shows that you don’t know a certain concept that you are supposed to know.” That was an important lesson — stick to the brief and deliver on it, rather than going beyond and messing it up. However, later on, I realised that simply sticking to the brief is not what leaders do.

I also learnt about true frugality. From the $120 I got as stipend every month, I paid my rent and food expenses, bought a stereo and a camera, made a trip to India, and even managed to buy a red Mustang!

Cornell really transformed my life forever. I had come a long way from Harpalpur. My language skills improved and I tried my hand at everything that came my way – bridge, of course, and then table tennis, ballroom and square dancing, swimming, skiing, etc. I never became good at any of these but that didn’t stop me from signing up for new stuff; I used to be up till 4 am most days. I don’t know how, but amid all those distractions, I managed to get good grades.

***

The job at General Motors (GM) was sheer happenstance. I had been rejected by GM already and was about to take up an AT&T offer or a teaching assignment at Pennsylvania State University. Then I got the call from GM asking if I was still interested. I readily agreed. Apparently, the department head changed and when Mr Neil Schilke saw my application, he told the HR person he wanted to hire me. They pointed out that I didn’t have an H-1 visa to which Neil replied, “My job is to get the right guy. Your job is to get him the visa.”

Neil taught me a crucial lesson that has stayed with me. I was late by a minute for one of our first meetings. He just looked at his watch and calmly told me to attend the meeting next time as this one had already started. I froze, didn’t know what to do. That was a hard lesson learnt on punctuality. I never dared turn up late for any meeting after that, except for one, a long time later. Call it Murphy’s Law or whatever, that meeting was with Anand Mahindra, just a few days after I joined Mahindra. But my reception this time was in sharp contrast. Anand Mahindra welcomed me, asked me to sit down and briefed me on what had been discussed before I came, so I was up to speed and could join in the discussion. That’s part of what makes Anand so respected. He’s inclusive, gives you a lot of respect, never puts you in a spot and never threatens you with anything. He makes you feel comfortable.

Back at GM, my language woes continued. As luck would have it , GM had great diversity, with an equal number of Chinese, Indian and American employees. Thankfully, there were many others, especially Chinese, who were not great in English and GM organised a 14-week one-on-one tutoring in both written and spoken English, and that helped me so much. Those English tuitions were a real saviour in my career, without which my growth may have been stunted.

The huge research labs and college kind of work style with no one breathing down your neck for any tangible output made GM Research Lab (GMR) a paradise for us researchers. GMR used to be seen by operating divisions as a white elephant but we thought GMR contributed a lot to GM — the number one auto company in the world.

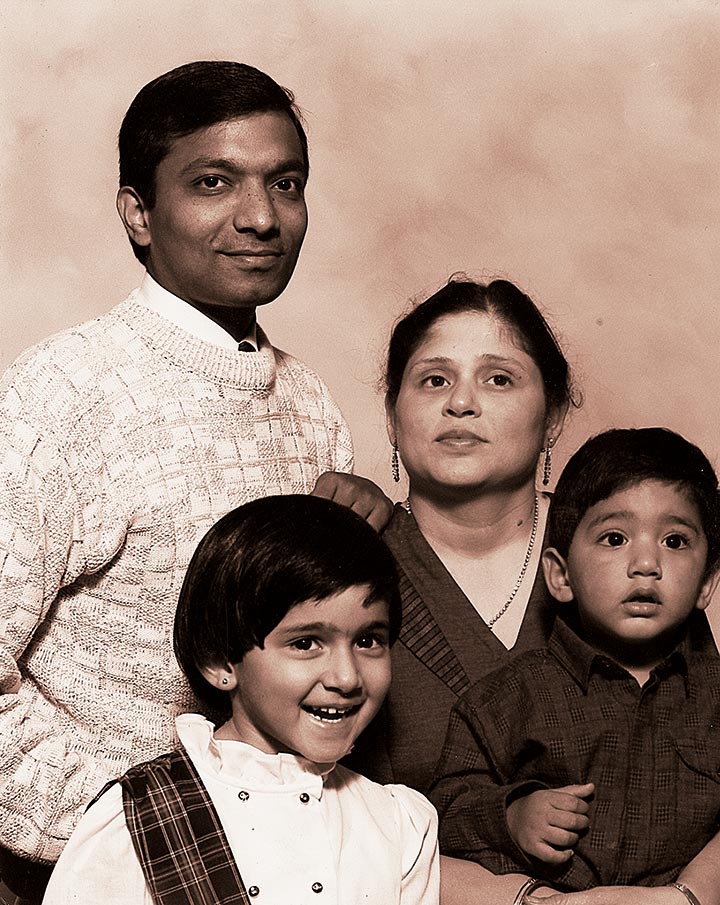

For me, those 14 years at GM were wonderful, both work wise and on the home front. The freedom, the satisfaction of building FLARE — a software solution for friction and lubrication design of automobile engines. FLARE put to good use my skill set in mechanical engineering and my love for programming. I was known as the father of FLARE. In all those 14 years I don’t recall taking any business calls at home, never worked on weekends, and could leave for home sharp at 6 pm (After all, I was the hard working type.) Mamta (my wife) and I had a ball and of course, when Pooja and Puneet came along, we had all the free time to enjoy with them. Financially, too, it was great — my first salary at GM, back in 1979, was $27,000. By the time I quit, it was over $100,000, with four promotions along the way — that was quite an achievement even by US standards.

***

A ghazal and a newspaper ad were the trigger for me to return to India. It was not easy to bid goodbye to such a cushy job but Mamta and I had been thinking about returning home. Hearing Pankaj Udhas’s Chitthi Aayi Hai would reduce me to tears. And when I saw Eicher’s full-page ad for a vacancy, urging NRIs to return home, Mamta and I looked at each other and simultaneously said, “Yes!” I decided to apply to a number of automobile companies and look for options on my next trip to India. Telco would have been my first choice.

Had it not been for the following factors — my mother, Air India, the 1992 Babri Masjid incident and the charisma of Anand Mahindra — I may not have joined Mahindra & Mahindra. My mother never wanted me to be out of Calcutta for more than a day. Air India was on strike and running few routes and the only place I could visit in a day was Bombay. I decided to go for the interview at Mahindra. But on the day of my interview, the Masjid demolition had led to riots and there was a bandh across Bombay. Only Anand Mahindra had come to the office, so he was the only one to interview me. His vision for R&D clinched the deal because I could not think of a better opportunity for an automotive engineer. He wanted to produce a world-class automotive centre and I was raring to go. Mahindra also worked better because the posting was in Nashik, closer to a metro like Mumbai.

I went back and tendered my resignation to my boss at GM, Nick Gallopoulos. He broke my heart with his initial reaction: “Okay, see you.” That’s it? I prided myself on being his best teammate and this unexpected reaction was heart-wrenching. An hour later, I received a note that put me at ease — he wrote that he was too stunned to react and did not know what to say and that he would speak to me next day.

GM not just gave me the greatest time of my life, but also the comfort of experimenting with my career. The kind of confidence you feel when you know someone will back you is immeasurable. GM gave me that, both time and backing. Even in the nine months I worked at GM after I resigned, the company gave me my due promotion. And when I left, they said they’ll keep the door open for me for four years — they treated my absence as unpaid leave. How many companies would do that? It gave me great comfort, especially as we were a tad worried whether our kids would be able to adjust. I made two promises to Mamta when we were leaving — if the children did not settle down well, we would head right back to the US; and even if we decided to stay back in India, we would send them to the US for their undergrad education and they would have the freedom to decide their own future thereafter.

I was excited about getting back to India, and having a larger role, but I can’t believe it even now what really made me come down from a $120,000 CTC to a Rs 7 lakh CTC. But we managed all right in India. This was one of the few decisions where I let my heart rule my head. I am glad I did it.

***

The initial months were a little tough. Although Anand Mahindra and Bharat Doshi wanted me on board, it seemed as if the team did not share the same view, perhaps they saw me as an intruder as they’d been working together for a long time. I was taken aback when my boss Parthasarathy, candidly told me he didn’t know why I was hired but would prepare me for the future anyway.

Their reaction was not entirely misplaced. Anand Mahindra had taken a huge leap of faith in me. At GM, I was at the highest technical level but had very little managerial experience. I had zero exposure to marketing, sales, product planning or the plant. I had worked in a narrow field for the past 14 years and was a purely technical person dealing with lubrication and designing bearings to reduce friction in engines. No one would have considered hiring me at such a responsible position. Anand Mahindra did.

True to his word, Parthasarathy did support me well. Thanks to him and Venkateshwaran, I turned from a specialist in a narrow field at GM to a generalist in automobile engineering. Over time, we all got comfortable working together and things started to fall in place.

Mahindra did everything to make me and the family feel settled in India. Our house was ready when we landed, school for the children, phone connection, gas cylinder; everything was taken care of. But I was so shocked to see the so-called R&D centre. On October 13, 1993, I was at a small shed in Nashik where the engine testing was done. It was about two acres and I asked where the rest of the R&D centre was. “This is it.” Even my specialised R&D lab at GM was about 10x larger!

I didn’t let my disappointment come to the fore though, at the back of my mind I always knew GM was still waiting, if I wanted to go back. I was also lucky to not be assigned any specific project right at the outset. Instead, I spent close to six months just learning the tricks of the trade and getting comfortable with the people.

I couldn’t believe it when Anand Mahindra told me in 1995 that I would be heading R&D. It was really a steep learning curve between 1993 and 2003 — from building on my engineering prowess to delivering a product that all of us could be proud of.

We first developed the chassis, and when I looked at the completed framework for the first time, my immediate reaction was that it was great but unaffordable; all I could see was cost everywhere. We had to bring it down to a level where it became affordable for us but at the same time we had to retain the design. We did that and built our current day pick up on that chassis. That product, even today, is very sought-after, cost effective and reasonably profitable.

Then came the Bolero. We had a product in Armada and we hired our first ever stylists, Ram and Shyam, who came up with the Bolero. That was right about the time we had set up our own dye shop, with the help of Fuji of Japan. I loved what I saw and when Anand came to Nashik and saw what we were doing with the Armada, he asked me what would be the investment. I had no clue, so I gave him a random number, something like Rs 20 crore! He exclaimed, “That’s a lot of money!” but in the same breath asked if we would use our own dye. I had no clue whether we could or should, but I just blurted “yes”, and he said, “Ok. Approved.” That was the extent of business case development done for the Bolero. It turned out, Rs 20 crore was not too far from what we invested. It also so happened that our guys could do the dye for it and Bolero became our biggest success, by far; even more than Scorpio in terms of number of vehicles we have sold (and the profit we have made).

Bolero allowed our designers and engineers to try their hand at something that was perhaps less risky and less of a stretch from where we were and prepared us to do something bigger with the Scorpio. In a manner of speaking, Scorpio was also done with a very simple brief: we needed to do a product that was a significant departure from what we had been doing until then. We formed a very small team of seven people, gave them an office and asked them to get to work. I was in charge of the project and since it was set up in Mumbai, I used to commute from Nashik.

I was told — and no one has ever confirmed this, so I don’t know how true it is — that there was a very good reason why I was chosen to head the project. Apparently, everybody could see this was a big project so during one of the early project meetings, there was a lot of push and pull as to who should head it. My name was thrown in because everyone thought a junior guy, sitting in Nashik — I had only been in the company four years — would be completely harmless. Whatever the truth, I’m thankful to whoever suggested my name, for that turned out to be a significant career-defining moment for me. What I am today is, to a large extent, thanks to the Scorpio project. It allowed me to move out of pure engineering to look at business as a whole.

But Scorpio days were testing times on the family front. Mamta had two bouts with breast cancer. Most other women would have wanted the husband by their bedside, but Mamta, the amazing woman that she is, asked me to focus on my work and said, she will take care of herself. She did not demand my time beyond what was absolutely unavoidable. She never gave me a whiff of how miserable she was. I shudder when I remember one particular instance when she was undergoing chemotherapy at Mumbai’s Tata Memorial Hospital. I was in Nashik, having a Scorpio review, when I got a call informing me that she had a reaction from the chemo and had been admitted to the ICU. She, in her feeble voice, told me that she was fine. Not to worry. I could complete my reviews and come the next day. I spoke with the doctor to check on her and to say that I will come the next day. There was a pause before the doctor said, “Dr Goenka, there may not be a tomorrow.” I dropped everything and rushed to Mumbai. It was the longest ever drive for me, from Nashik to Mumbai.

Mamta’s attitude has taught me the biggest lesson in life — never be fazed by adversity; look for the silver lining instead. She always says that, in any situation, only 10% is what is happening to you and 90% is how you react to the situation. Throughout her treatment, she remained so calm and collected. She says she is blessed to have all the support and resources to go through her bad phase. Most others, who she meets in the hospital, do not have anybody to fend for them and lack resources in every way. Mamta’s battle with cancer gave her a new purpose in life — to help cancer patients survive the psychological trauma of the disease. She has become quite a speaker!

Those difficult days had to give way to something better. As a project leader, I got credit for the Scorpio but truth be told, three things worked for the Scorpio. Apart from the product itself, which was great, we did something different on marketing. Rajesh Jejurikar, who had just joined the company, decided not to call it an SUV, but a car – one that you can walk into — and instead of naming it Mahindra Scorpio, he called it Scorpio by Mahindra. The third factor was that people did feel a sense of pride thinking here was an SUV by an Indian company, and were willing to overlook a few shortcomings.

When the Scorpio was being built, our investor relations people wanted to showcase what we were doing at Nashik. But we had nothing to show them because it was all work in progress. I got a bright idea: I put barricades all around and said that I could not take people behind because it was confidential and all investers went back very impressed.

Given how important this project was for the company, all the best resources were made available for the Scorpio project by Alan Durante (my immediate boss) and Anand Mahindra. I had the best of everything, including many gurus. Johnny Mapgaonkar, who was the purchase head, taught me all about negotiations and how to select suppliers; Winston D’Souza taught me manufacturing; Ajay Choksey was my finance guru; and from Jejurikar I picked up some marketing basics.

Johnny taught me the Narasimha Rao strategy — essentially, let the other person do the talking and let him think he’s not getting through. He will keep coming down slowly to where you want to be. Whoever talks reveals his hand. That’s when I also learnt that negotiation is not about arm twisting — it is about creating value you can share, because both parties are sitting at the table to get something out of it; nobody is going to sell you something at a loss. It’s about creating value and sharing value, rather than transferring from one hand to another.

Those initial supplier meetings were exciting. For example, we had the choice of going to well-proven established suppliers of weld lines or a company such as Wooshin from Korea that had never before done a complete body weld line. The difference in price was 2:1. Johnny, Durante and I sat down to decide — nobody was brave enough to say, let’s do it, because it was a big risk. If Wooshin faltered on supply, the whole project would be back to square one. None of us had ever done a new bodyshop; we were all playing blind. So, we called the Wooshin team over to Taj Land’s End again, tried to build our own confidence in their capabilities, and finally Durante said, “Let's take the plunge”. We were on a thin budget — Rs 600 crore — we needed to take many such risky decisions at every level. In the end, it worked out very well and many of these small relatively unknown suppliers have grown with us and become big.

Bharat Doshi and I visited CK Prahalad at his house in the US — Bharat was great friends with Prahalad. And we were discussing how to make this low cost, world class product a reality. And Prahalad said something very simple, “You need to show the suppliers the carrot in India right now and they’ll do anything for you because all these guys are hungry to get into India; it’s the biggest growth market.” He suggested that instead of spending money, we should demand money for the business we give global suppliers. We tried, and it worked like magic.

Lear Corporation had set up factories in India but had very little business and wanted our business. We negotiated with them much beyond Scorpio and we said, “You can have our entire seating business but you have to do a few things: pay a certain amount of money to the company upfront to get the entire business; bear the cost of engineering and tooling and ensure our current suppliers are not out of work.” Rati Puri came from an investment banking background and had just taken over Lear India. He was shocked at our audacity. We held our ground and said, “Well, yes, we are the largest possible business in India, so the deal is fair.” They signed the deal.

The advantage with Scorpio was that several suppliers were willing to work on the product because they could all see that the car had the potential of becoming a high-volume product in India. Most heartening was that we were able to take many Indian suppliers from “built to print” to “art to part” suppliers.

***

Much later, I saw Durante negotiating the deal with Renault. The most difficult part of the negotiations was to get 51% ownership. Renault wanted 51% because they were a big multinational company, they were bringing the technology and we would be riding on their strength. Durante was very keen on the partnership; it was his idea to get a partner to utilise our Nashik plant better, but he just did not budge. I saw the Narasimha Rao strategy play out all over again — and we got the 51%.

I first met Alan in Detroit, after I had decided to join Mahindra. We met for breakfast and his first question was, “Are you a US citizen?” I said no, to which he snapped, “What’s wrong with you?” I said I had never felt the need and now I would be moving to India, so it was unnecessary. He insisted that I apply for US citizenship and I did. During my Scorpio days, we had great fun travelling together all over the world — Europe, Southeast Asia, Japan. But wherever we went, he made it a point to remind me that it was only because of him that I was a US citizen and that was what was making my global travel so easy.

As a boss, Durante was very aggressive, bossy, impatient. No one could tell him: that something cannot be done. He would easily lose his cool and be extremely blunt, which was not easy to deal with. In the initial days of reporting to him — I think it was 1998 — we were in a meeting with five others and he said something like, “Have you left your brains at home?” As soon as the meeting ended, I went up to his cabin and told him that he could say anything to me in private, but could not ridicule me in public. He never did that again.

Durante could get people on his side despite his aggression only because he himself was so committed. When the Scorpio prototype was ready, he drove it himself from Mumbai to Goa to get a first-hand feel of what the product was like. The day he came back he called three of us —Jayanta Deb, Ravi Deshmukh and me — home that very evening. He was curt. The car was not handling well. We had to go back to the drawing board and fix a few things — only those “few” things were actually a long list. It would be an understatement to say he drove us hard. On the other hand, but for him, we would have overlooked quite some flaws, thinking it would be acceptable.

In June 2003, Anand announced I would take over as COO, with the intention of making me CEO when Durante retired two years later. It’s rare for an R&D person to get into the general management role, especially in India but Durante made the transition remarkably smooth — he made the entire team report to me, except international operations and HR. Transition usually brings two problems — you leave your comfort zone and have to deal with something new; and you are suddenly lonely because you no longer have your peers around. Neither of those became issues for me because Durante was there to see me through the entire exercise.

Parthasarathy had prepared me for R&D and Durante coached me to be a well-rounded business leader. He took it upon himself to mentor me and make me a better leader. He was a very effective leader himself, yet he had the wisdom to tell me: each one has his own style of working and what worked for him may not work for me, so I should stick to my own style. That advice from someone who had put in 43 years in the company to rise right to the top reinstated my faith in my own ways.

What also helped was Anand’s decision to send me to Harvard for an AMP. It may not have made much difference except Durante insisted that I would not attend any office work during the nine weeks of the course. That period allowed me to think how I’d like to change the way the business is managed. My aim was to try and make the organisation better than it was — one simple but effective lesson I learnt was to make a three-year promise statement, which then becomes the blueprint on how the business will move forward.

The 2004 blue chip conference at JW Marriott was inarguably the lowest point of my career. Anand Mahindra had gotten this film made without our knowledge about how customers react to Mahindra products. It reflected poorly on us, to put it mildly. That year we were at the bottom of the customer satisfaction index and especially after the glorious launch of Scorpio, this was a huge setback. At the customary photo shoot, after the conference, I stood in the last row, thinking to myself I had to earn my right to be in the first row.

From the hotel, I headed back to my home and shot out a very emotional mail to the officers of the automotive business. I was feeling terrible. But we worked harder than ever. We gained positions in customer satisfaction slowly but steadily. And 11 years later we were rated first in sales satisfaction. This was one of the proudest moments of my career. Anand Mahindra often recalls the episode, appreciating the team on how we determinedly clawed back.

Jejurikar’s suggestion of making our customer service commitment more authentic by projecting a Mahindra face worked wonders. Of course, he conned me into bearing the brunt of shooting an entire day for a 30-second commercial. And later, I had to handle a phone call from the lady who called in to correct my pronunciation from sa to sha in the word Koshish — many Marwaris can’t pronounce sh and I am no exception; she spent several minutes asking me to repeat it again and again, and then she gave up. I still don’t know who that mystery woman was.

***

Xylo was a painful lesson. We launched it after an eight-year gap as a people mover — a sturdy car that was roomy and comfortable. Sure, it would not win any beauty contests but we were confident that was not what people wanted in a people mover, anyway. We were so wrong — design expectations of Indians were just soaring and Xylo didn’t make the cut.

Sometimes, logic and analytical abilities just do not help. Many years ago, Anand Mahindra told me that it’s good to be analytical but in the process one should not lose out on the big picture. He has always felt I needed to bring in more intuition into my analytical thinking. But he never makes you feel he is pointing out a shortcoming. “Pawan, whenever I have seen you using your strong intuition, it has worked very well. You should use it more often.” I could relate to that. Mamta, too, complains that I analyse everything a bit too much, which takes away the charm. Thanks to Mamta and Anand, my right brain has began to contribute more.

The Xylo jolt drove us to focus all our energies on the design for the XUV. So much so, that we began thinking perhaps the aggressive design would backfire. But when I saw the first physical model in 2009, my first thought was, why should we not strive for it to be the highest selling SUV in the world? It had all the features a customer would look for. Anand Mahindra said the same. That didn’t happen. But what a hit it became when it was launched in 2011. When we displayed the prototype at the Johannesburg Motor Show, no one believed it was Indian made. That was a high point.

It’s amazing how we made such a huge success out of a model we started developing from dingy sheds! The Scorpio started with just about 5,000 sq ft of space in the western suburb of Kandivali in Mumbai; even the XUV started in a small shed in Chennai because we wanted to have the team in Chennai, rather than make them work in Kandivali and then move them to MVR where the R&D center was to be built.

We had a great run, with three hits within a span of 10 years, but we have had our share of testing times as well. Q4 2009 was truly a wake-up call — the automotive business suffered a Rs 1-crore loss. In the 92 quarters that I have been at Mahindra, that was the only quarter when we had a loss. But it was good we had that loss because it was a bigger jolt than turning in a profit, however small, would have been; everyone was shaken up. All I could think of was not to let the slowdown go to waste. We trimmed the fat but continued with our product development and did not cut any cost. The four-year investment cycle invariably plays out, and in 2013 we were back with a bang! When the rest of the industry was still under pressure, we had our best years — the highest marketshare and the highest margins.

***

The SsangYong acquisition happened so quickly, it was impossible to believe we cut such a perfect deal. We first heard about the offer in June 2010; by November we had wrapped up the deal; and by March we had acquired the shares. Abhinav Grover was just so phenomenal in tabling the winning bid — by creating scenarios of possible competing bids and putting in just the right offer.

In any organisation, people are truly the centrepiece in your success. Unless we had got the aspirations of people of SsangYong aligned with ours, there was no way we could have succeeded with the acquisition. That was our experience even with Satyam and Swaraj. SsangYong was almost bankrupt; the feeling was that the earlier owner, a Chinese company, was interested only in the technology, which they took away and made no effort to turnaround the company. Obviously, the company was in poor shape, and the union did not want the same story to repeat. It wanted the acquirer to be morally and legally bound to act in the interest of SsangYong. After several rounds of discussions with the union, and many sleepless nights later, Ketan Doshi and Rajeshwar Tripathi negotiated a tripartite agreement between SsangYong, its management and Mahindra with no end date – never in history have such agreements been signed and that too with no end date! That landmark document is referred to even today, six years later. It’s amazing how SsangYong had not had a single labour strike in all these years — it’s unheard of in the automotive industry in Korea.

***

In the farm sector we were a market leader, but not seen as a technology leader. Building tractors is far more tricky — in passenger cars, the expectations of customers are broadly the same: reliability, comfort, design, mileage. In tractors, every customer wants something different because the soil, crops and farming practices vary across the country and each place would require a different deliverable. We nailed it with the Yuvo, which became a big hit. Our approach was simple. The starting point was to make a list of 10 rational reasons why a customer will choose Yuvo over any other tractor. And that became our mission statement. Yuvo was tested for 50 different applications making it the most versatile tractor.

***

What a journey it has been. From my reaction initially of shock and surprise at the size of the R&D centre, to seeing it as an opportunity, to making it an accomplishment. I’m happy we took the decision to move to India with my heart and not my head.

My life has been largely shaped by chance happenings; I am glad that the happy coincidences weighed in. I have also been lucky enough to survive several potentially life-threatening incidents — getting thrown off the cliff in a car accident during my Cornell days; lost in the snow for six hours while skiing the mountains in Colorado; getting pulled in by the current in the Cayuga Lake. That, and lastly, Mamta’s battle with cancer. All of these have given me a healthy respect for life and a desire to make the most of it.

What has always worked for me is that I don’t pretend to be someone I am not; never put on a façade, a mask. If you are always what you are, then, you don’t have to try and remember what you were last time.