Like every year, world leaders and corporate biggies were keeping their date with Davos, debating ways of “cooperation in a fragmented world” at the World Economic Forum. Also, in attendance this year was Sequoia Capital’s managing director for India and Southeast Asia Shailendra Singh. At the same time, 6,700 kilometres away from Switzerland, in India, his colleagues were caught up in a different debate. As Singh, the protagonist, or maybe the tragic hero of our story, hobnobbed with the who’s who from the private and government, was his mind pre-occupied with the storm that was brewing in India?

Of course, he knew that his trusted lieutenants were already looking into the concerns raised by EY in GoMechanic, an Indian start-up Sequoia is invested in. Sources say that the venture capital (VC) firm wanted the founder of the company to come clean on its blunders. Many say that it was an attempt by the VC firm to wash its hands off the goings-on in a fraud-hit start-up, while others point to how it was in keeping with Sequoia’s “zero tolerance towards proven wrongdoing”.

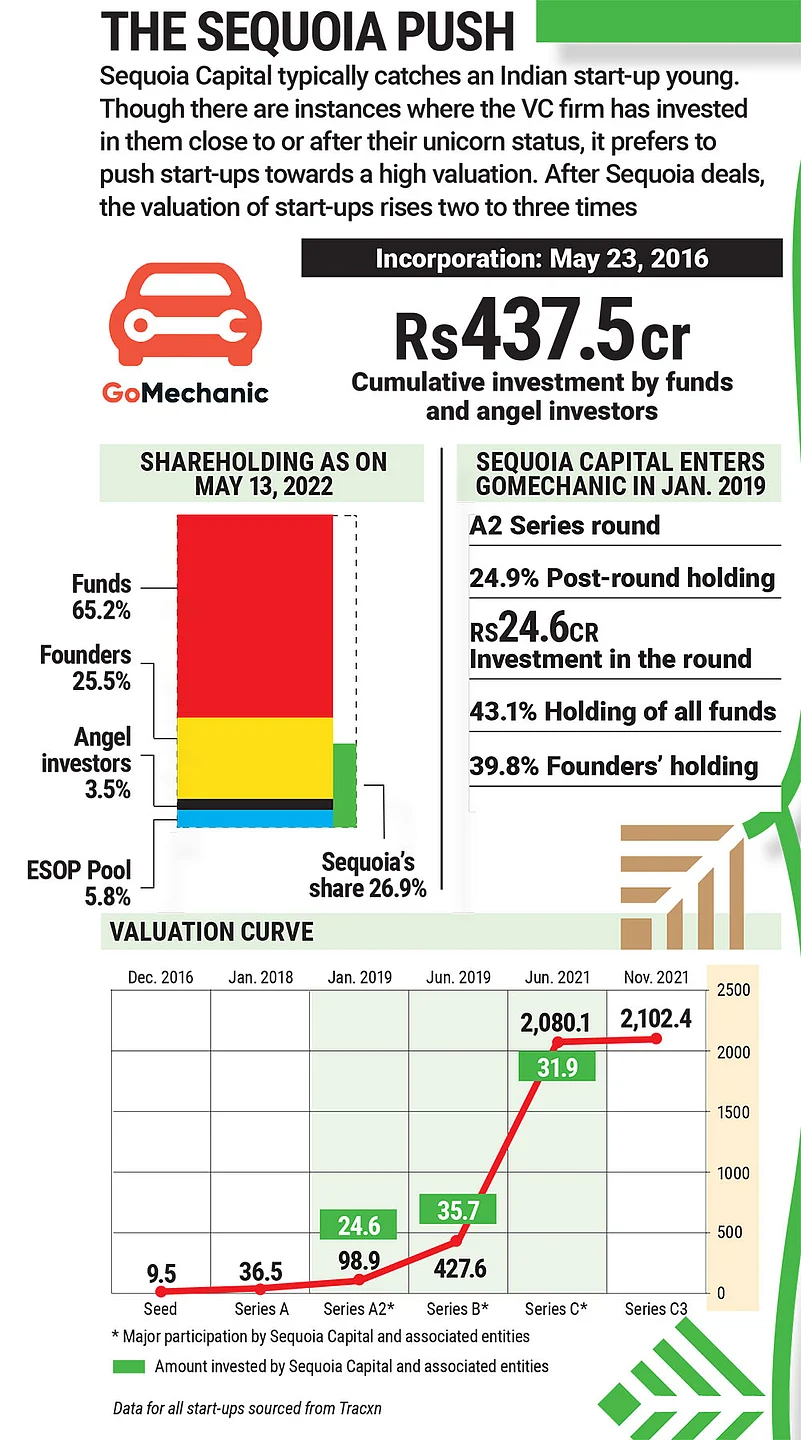

In an unusual move in the Indian start-up sector, on January 19, GoMechanic’s co-founder Amit Bhasin took to LinkedIn and admitted to cooking the books of his start-up. Sequoia invested in GoMechanic in 2019, three years after Bhasin and his three co-founders started the multi-brand car service company. In a post reminiscent of the 2009 Satyam scam, when promoter Ramalinga Raju admitted to cooking books to hide diversion of funds, GoMechanic’s Bhasin confessed to “errors in judgement” for chasing “growth at all costs”. This has become a case all too familiar now in the Indian start-up world: that is, reporting revenue at any cost for higher valuation. You have heard this story earlier when Byju’s unravelled, Zilingo hit headlines before that and the sordid saga of BharatPe even before that. The unkind point to common factors here, Sequoia and, more specifically, Shailendra Singh. Like Greek heroes, he has lost a few unicorns on the start-up stage and his personal brand and kingdom are under attack.

There are close to a dozen managing directors on board Sequoia in its India and Southeast Asia operations, but everyone seems to single out Singh whenever a controversy erupts, even when he is not part of the board of the company that catches fire. The obvious reason is that Singh, as managing director, is part of all important verticals of Sequoia in the subcontinent and Southeast Asia. “His tenure, combined with his stature, makes Shailendra Singh the last word in Sequoia,” says a founder of a start-up in which the VC firm has invested.

A Star Rises

The thing with Greek tragedies is that all seems to go well for the protagonist till it does not. When things go rapidly south, it is always a combination of circumstances and personal failings amidst grand designs. But till the climax arrives, the hero seems without moral or material fault. So was Singh and his relationship with the Indian start-up sector. He was its unblemished high priest.

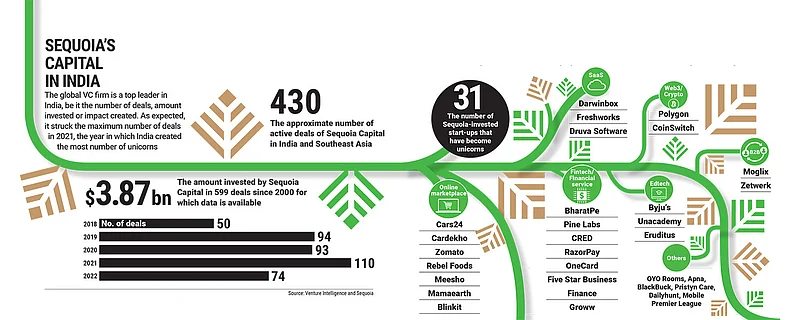

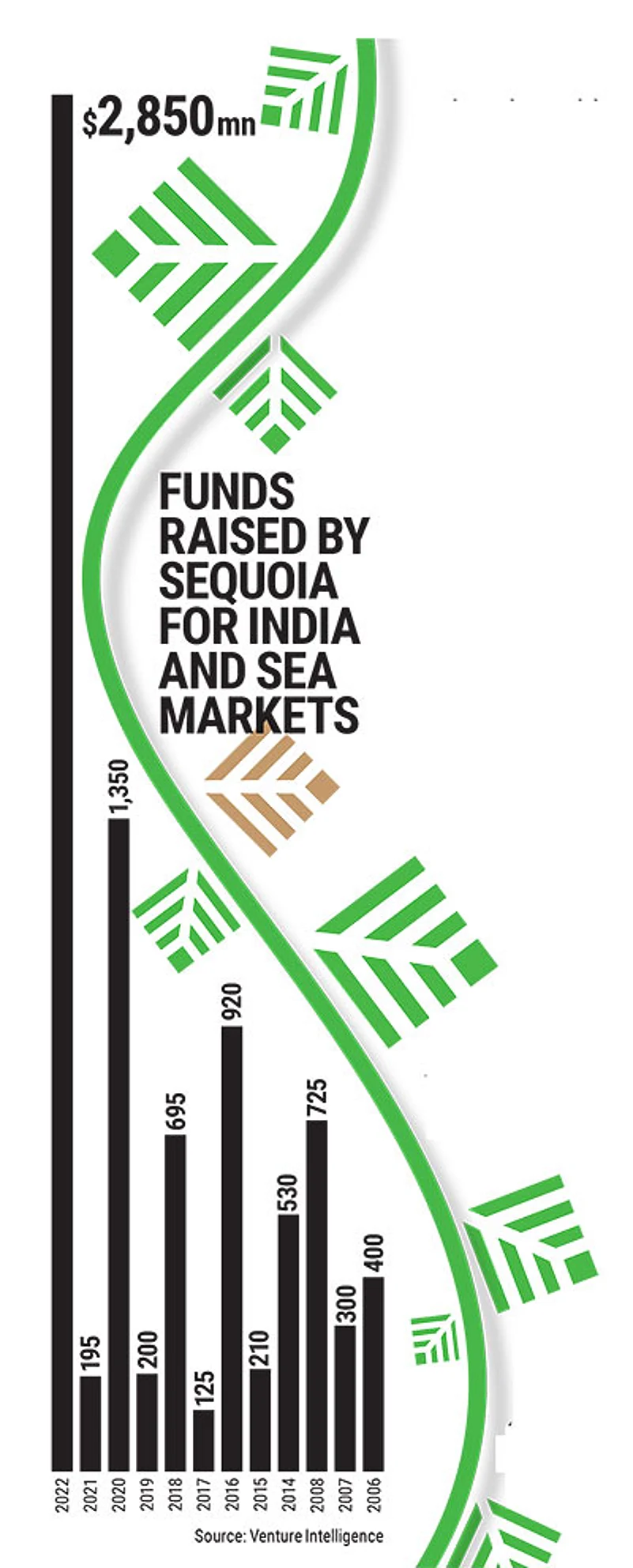

Sequoia leads the pack of venture capital firms in India. It started backing Indian founders well before start-up and entrepreneurship became buzzwords in the country. According to the market research firm Venture Intelligence, Sequoia participated in 50 deals in 2018, followed by 94 and 93 in 2019 and 2020 respectively and peaking at 110 in 2021, when India produced a record number of unicorns. Even in 2022, a year seen as dull for start-up funding, it participated in 74 deals.

No wonder then that any issue that afflicts the Indian start-up sector today has a Sequoia connection to it from yesterday. And, given Singh’s long stay at the helm—over 17 years to be precise—his name crops up every time an investee company is in the news for the right or wrong reason. Of late, Singh and his team have found themselves caught in the crosshairs as some of their bets have imploded in close succession.

The world of venture capital stays opaque in India, but its story can be pieced together through the voices of its multifarious cast. While some actors take centre stage, there are several voices that lurk in the background, the ones which refuse to be identified but shed light on the protagonist’s character and moves to explain why things unfold the way they do.

By all accounts, in the days following Sequoia’s founders splitting to set up WestBridge Capital, Singh emerged as its most influential partner in India. Start-up lore is filled with anecdotes of how Singh’s bets in India and Southeast Asia helped the global VC firm shed its early conservative approach to investing. While Sequoia missed out on investing in Flipkart and Paytm, Singh closed deals with the likes of Kunal Shah’s Freecharge within minutes of the pitch.

“In a VC firm, there is always a personality cult. It has that one person who is most powerful. Sequoia in India is no different. On paper, he along with 10 others might have the same designation, but even in the investment committee, there is one who is the first among equals. In this case, it is Shailendra Singh,” says a senior executive at a rival VC firm.

Singh has had a stellar run so far at the global VC firm, as a large number of his India and Southeast Asia bets have paid off, giving its limited partners (LPs) handsome profits on their investments. (Limited partners invest money in VC firms and could be individuals, family offices, foundations, etc.) Some of Sequoia’s storied bets include Tokopedia and Gojek outside India and Pine Labs, Zomato and CRED, among many others, in the country.

“Shailendra Singh is known for taking asymmetric bets to give outsized returns,” says the founder of a tech start-up in which Sequoia invested seven years back. The going was good till some of these bets blew up, the founder adds. “With such high risks and returns, there are bound to be some public relation disasters,” the founder says.

Bold, aggressive, and workaholic are the adjectives most use to describe the 46-year-old Singh, quickly adding that these are flattering qualities for a venture capitalist, had one controversy after another not hounded him. “Given the size of its cheques, Sequoia has no competition in India. And, then, there is the confidence that LPs repose in it [as] their returns from Sequoia are unmatched. Even if two out of 10 bets go kaput, the LPs are already sitting on multiple X on their investment in those two start-ups,” says an investment banker, who has close contacts with Sequoia in India. In fact, insiders say how, in a recent meeting with a prominent limited partner, Singh volunteered details about the recent controversies at GoMechanic and Byju’s only to be reassured of the absolute faith the LP has in Sequoia’s business decisions.

“But all LPs are not the same. Some like IFC, pension funds and most foundations are extremely conscious about the investments of their fund managers. They see it as a reputational risk if there are corporate governance lapses in portfolio companies of their fund managers,” adds an executive at a rival VC firm.

The biggest reputational risk is to Sequoia, a 50-year-old fund house that has reared companies such as Apple and Google. So far, the controversies are in less than 1% of the firm’s portfolio in India and Southeast Asia, as per Singh’s own admission, and many believe that the singling out of Singh and his team is the doing of their rivals. Sequoia’s American bosses are also happy to contend with this version so far. But rumours are abuzz that a few more Sequoia-backed start-ups are on the boil. What happens if the rumours turn out to be true?

Clouds are also gathering elsewhere. New Delhi is concerned. Particularly after the confessions of the GoMechanic founder, top echelons of the government are worried about the impact such controversies can have on India’s image as a global start-up hub. Singh knows about it. Political leaders told him as much when they met in Davos.

Sources say that the government has a few options under the Companies Act to instil accountability in the start-up sector. For example, the Serious Fraud Investigation Office, or SFIO, could be called into action. It has the authority to start a suo moto probe, but it cannot be mobilised for start-ups of all shapes and sizes, says the source. The opinion is that the size of a start-up and what constitutes serious fraud need to be defined.

“The idea is not to kill the pace of operations in a start-up but to ensure that financial and legal best practices are followed. Start-ups are listed companies of the future and their valuation is dependent mostly on their reach, so there needs to be a mechanism to ensure that their claims are verified by authorities,” says a senior bureaucrat.

Any investigation into financial irregularities in a start-up is not likely to stop at the examination of books but may get extended to probing the role of its directors. Indian authorities are infamous for their strict enforcement procedures, so it could be in the interest of fund managers that the government does not ponder on its options.

The Script Flips

While the charitable observer may consider the GoMechanic fiasco a one-off episode and Singh’s role in it rather incidental, the current crisis at Sequoia was building up for some time. Its first major crisis in India took place in 2015, when Singh had a public spat with Housing.com founder Rahul Yadav, with the latter accusing him of poaching the property platform’s employees. Things between a very young Yadav and Singh escalated to such an extent that in an email to Singh, Yadav proclaimed, “This marks the beginning of the end of Sequoia Cap in India.” Though Yadav expressed regret at his spat with the investors later, it brought a loss of image to Singh and Sequoia.

Much later, this act would repeat itself in the BharatPe case, which gave rise to a full-blown founder-versus-funder debate in the country.

The dust had barely settled on the Housing.com issue that, in 2016, Sequoia came on the radar of the Enforcement Directorate. Its Bengaluru office was raided during a probe into its investee company, Chennai-based Vasan Healthcare, on the charges of it diverting funds to businesses associated with Karthi Chidambaram, a Congress member of Parliament and son of former finance minister P. Chidambaram.

These two episodes show that Sequoia under Singh invited questions both on the ethics of corporate governance, which is seen more as a moral issue, as well as the legal standing of its investments. These themes kept repeating themselves irrespective of the sector the VC firm invested in.

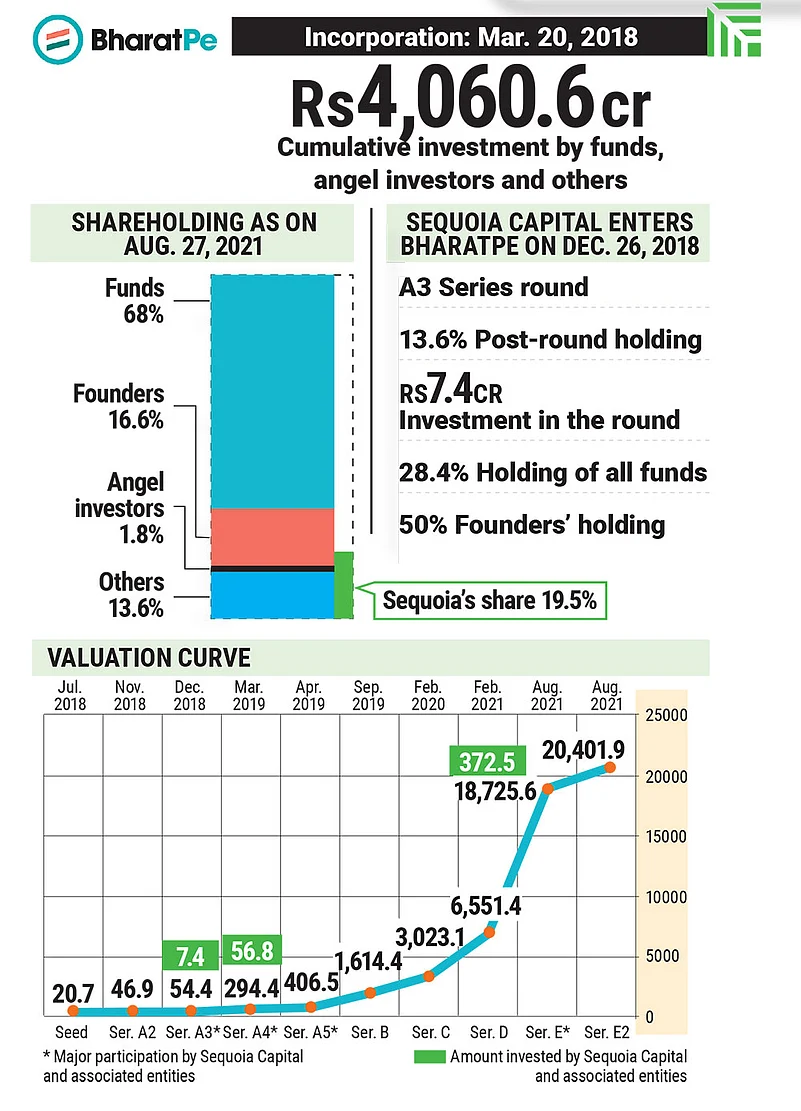

Perhaps Singh’s image took its worst beating in the BharatPe saga, where the friction between founders and the Sequoia team made news headlines. Company co-founder Ashneer Grover took on Sequoia and turned the episode into not just a founder-vs-funder duel but also a nationalist issue. Sequoia’s managing director Harshjit Sethi was on the fintech company’s board, but Singh’s silhouette was seen in the episode as the media reported how mails about the goings-on in the unicorn were marked to him. Sequoia’s holding of 19.6% in BharatPe makes it the largest stakeholder in the fintech firm.

Zetwerk was the next in line when, in 2022, income tax officers searched the manufacturing services platform’s offices and warehouses and the residence of its founders for allegations of suspected tax evasion. Similarly, last March, social ecommerce platform Trell came under the scanner when a forensic audit by EY probed it for financial irregularities.

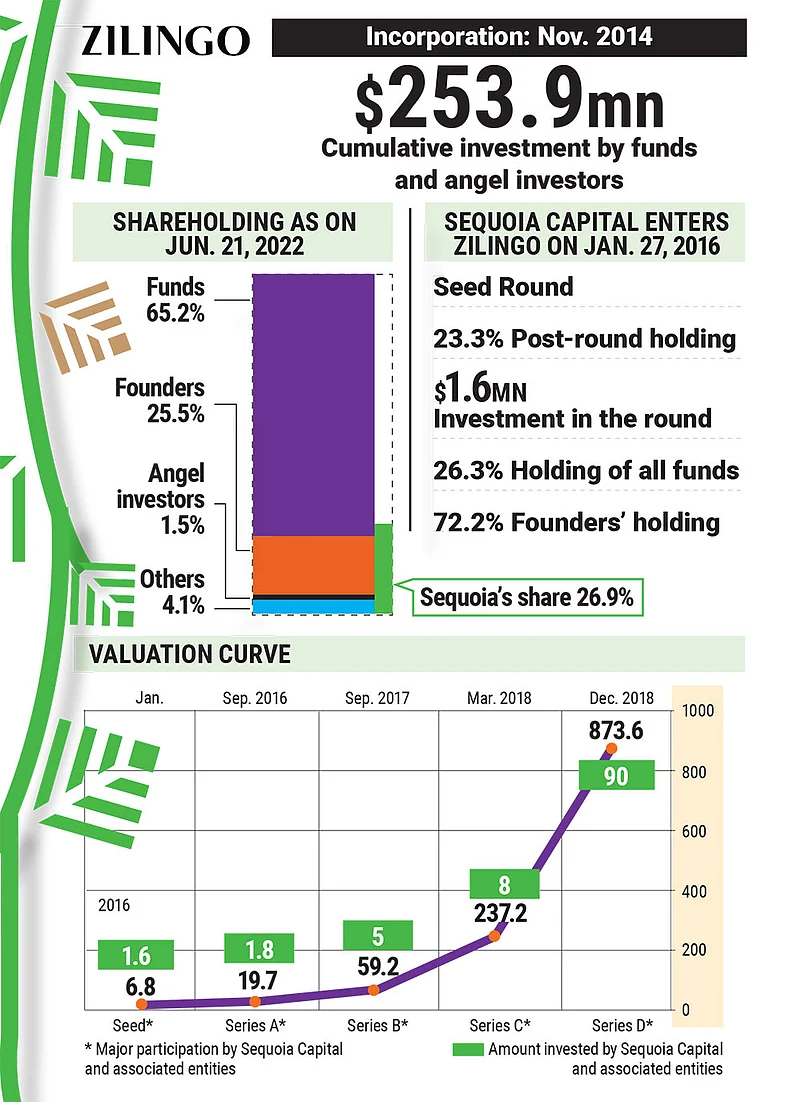

This build-up led to alarm bells ringing—even in the media, which celebrates loud moves by VCs and rarely asks critical questions—when Singapore-based fashion tech company Zilingo was caught in a quagmire of non-business irregularities, resulting in the dismissal of its 31-year-old co-founder and CEO Ankiti Bose in May 2022. The founder maintained that the high-decibel drama that played out for months was a “witch-hunt” and she was a scapegoat for decisions taken by the company’s directors. Like Grover, she blamed Sequoia and its top management for things going wrong. Singh was one of the directors in Zilingo, but he later stepped down from the position.

The Zilingo fiasco is perhaps what Singh feels the worst about. For him it was a personal failure, as he had spotted Bose and was her mentor.

But this was not the end of troubles for Singh. More bad press was just round the corner. First a delay in closing $2.8 billion India and Southeast Asia fund last year raised questions and eyebrows about the state of trust of its limited partners, and then questions on Byju’s financial declarations made Sequoia uncomfortable. Controversies were stacking up against Singh and Sequoia.

Karthi Chidambaram made another entry in the tragic tale of Sequoia, albeit in a different cast. He called into question the accounting practices at its crown jewel Byju’s and the edtech company’s inability to file its 2020–21 financials for 18 months. Once considered India’s most promising start-up, auditor Deloitte raised concerns about compliance issues at Byju’s, while there were also allegations of mis-selling and over-selling by the edtech decacorn along with its financial instability following a spate of high-value acquisitions with losses rocketing to Rs 4,589 crore in 2020–21 from Rs 232 crore in the previous fiscal. The start-up was also in the spotlight for several rounds of layoffs, and questions abounded about the profitability of the edtech, which Sequoia’s managing director G.V. Ravishankar was hard-pressed to answer.

From time to time, the VC firm has made statements about its “zero tolerance towards proven wrongdoing”, but the encore has now become too hot to handle for Singh and his team.

The concerns against Sequoia are many, and since the identity of the firm merges with its most prolific representatives, they are mostly aimed at Singh and his team, which includes Mohit Bhatnagar and Ravishankar. All three joined the VC firm around the same time in 2006, thus shaping the firm to its current avatar in India and Southeast Asia. Interestingly, both Singh and Bhatnagar have tried their hands at starting up. For Singh, entrepreneurship has a deep personal connect. His elder brother, whom he lost to cancer, was a fearless entrepreneur. His dynamism left a mark on Singh.

Born in Kanpur, Singh checks all boxes on academic pedigree, with an IIT and a Harvard thrown in for good measure. He worked at Bain & Co. before joining Sequoia. “Workaholic”, “teetotaller” and “motivated by the aspiration to give back to society” are the ways in which Singh loves to describe himself. According to him, he fulfils the third aspiration by making money for the non-profit organisations that are his limited partners at Sequoia. Unlike partners at different VC firms of his stature, Singh claims to not hold materialistic possessions dear. He does not have a Montana ranch or own a private yacht. In fact, he has not bought a house since he started working, Singh takes pride in stating.

India is an emerging market with a hyped demographic dividend, abundant tech and business talent and enthusiastic policymakers rallying behind the start-up sector. The enviable success of Singh and his team and the rise of Indian start-ups as a sunshine sector have in the past decade fed into each other.

Forbes lists Singh as one of the top tech investors in its Midas List (though he dropped off in 2021). The magazine called him the man who “helped Sequoia India become the country’s biggest venture capital firm and also led its expansion into Southeast Asia six years ago”. Singh hates accolades; it is about the firm and not him, he says repeatedly, claim those who know him well.

Burning Sensations

Unprecedented expansion has a cost and gives VCs a character. “There is a reason why VCs are called sharks. They are known to be focused only on one thing, which is growth. And, Shailendra Singh fits the bill to a tee,” says a founder who is also an angel investor.

Once Singh developed this reputation, it started making founders wary, especially the ones who thought that they had gathered enough muscle to resist big VC cheques. In this setting, Singh met Flipkart’s top team, including the Bansal duo, at a restaurant. It was an uncomfortable meeting by all versions. Those in the know say that the Bansals were keen on building the business at Flipkart and not get caught in the “valuation game”, while Singh stressed on the latter. No prizes for guessing that the deal never happened. Other observers say that the Bansals could nonchalantly rebuff Singh on the valuation approach because they knew that Flipkart had many suitors. On the one hand, Amazon was wooing it, and, on the other, General Atlantic had almost made a unicorn-like offer to Flipkart and Sachin Bansal was about to fly to the US to sign the deal.

An observer of the early ecommerce developments in India says that the Bansals were dismissive of Singh’s approach in the very first meeting, as they thought that if they accepted Singh’s offer, it would harm the business logic of Flipkart. “Singh expects founders to become investeetutes once he invests in their start-ups,” the observer says, adding that the suggestive wordplay describes the investor-investee relationship after multiple rounds of funding take place. The source alludes to how an investment from Sequoia would also mean key positions being filled with people the VC firm brings in, an apparently innocuous move to get in the right talent from the ecosystem, but the underlying allegation is of concentration of power in the hands of the investor. “Singh’s typical strategy is to zero in on a weak link among the founders, bet on him/her while driving a wedge in the top team and then bring their chosen ones to do his bidding,” the observer adds.

The casualties of pursuing the valuation strategy single-mindedly are corporate governance and best practices that are essential to creating multigenerational companies with lasting leadership. Ironically, these are the two phrases that Sequoia and Singh hold dear.

Outlook Business spoke with a large number of stakeholders in the start-up sector on the issue of corporate governance and the role of investors in it. The dominant opinion among them is that the behaviour of VCs is such that corporate governance is never a consideration for them—and Sequoia is no exception to this behaviour—as the focus is firmly on growth in valuation where burn is not a bad word.

One founder tells us how in all their meetings since Sequoia invested in the start-up seven years back, not even once did the VC firm insist on getting the “big four to audit the start-up”. “The focus is on customer acquisition, so the general understanding is that burn is the way to go,” says the founder.

Another founder, and angel investor, corroborates the burn doctrine, popularly called the loss-leader strategy in the start-up lexicon and which has many takers globally, and describes the extent to which founders are pushed to build brand and acquire customers rather than chase unit economics. “Globally, 40% of every VC dollar goes to Google and Facebook or straight to digital marketing. That is an interesting statistic to keep in mind. This is insane, because they are surrendering equity in their company for this!” he says.

A mindless chase for the loss-leader strategy is geared towards cocking a snook at the very logic of entrepreneurship of making a profit-making business entity. While companies in the Sequoia stable are masters of this game, Singh can take consolation in the fact that this is a global approach being followed by top VCs in the world at the cost of corporate governance. The interesting thing about this game is that most stakeholders, including founders and the next set of investors, know the reality and still play it. “As long as the MIS shows growth that can be directly related to increasing valuations, no questions about best practices or corporate governance are asked,” says one founder. “The key performance indicators, or KPIs, keep shifting,” says another. First it was about customer acquisition; with global fund flow facing headwinds, the narrative now has shifted to revenue generation.

“VC firms, such as Sequoia, have successfully managed to delink growth from profit. So, creating a viable revenue model became a big selling story; a viable business model was not the focus. All this is done to justify the next round of investment,” says a senior executive of a global consultancy firm who works closely with Sequoia in India. “The next investor also knows what is happening and is just waiting to palm off this story to the investor after him,” the senior executive explains.

This model showed early cracks in 2019 with the OYO crisis, a company that Sequoia has been backing since 2014. With a loss of over $25 million per month, its young founder Ritesh Agarwal, under tremendous pressure from investors and the media, moved swiftly to laying off employees and shutting a few non-performing business units. But that was not enough to keep the valuation intact. As was widely reported, Agarwal then invested at a higher valuation in OYO Rooms, allegedly with a loan from Softbank, all to keep the valuation intact and growing.

That Agarwal could do it without there being any probing questions from investors shows the philosophy that India’s start-up sector has adopted.

A similar turn of events panned out at Byju’s last year when after all the allegations of a lack of compliance, it still managed to announce a $800 million fund-raising round, taking its valuation to $22 billion. This episode confounded even the industry veterans. Quoting its losses and valuation, industrialist Harsh Goenka tweeted, “Nothing is making sense to me! Can anyone explain please?” To which, Biocon’s Kiran Mazumdar Shaw replied, “It’s like virtual reality - now you see it now you don’t. Valuations just don’t stack up n yet real businesses are under valued!”

Just like Agarwal’s move, Byju’s founder Byju Raveendran is also investing in the Series F round, obviously to keep the valuation intact and their VC backers happy. That Byju’s is yet to close the round is a story for another day.

“In all of this, the power of Sequoia in the Indian start-up sector is immense. The fact that questions about profitability as a measure of a viable business model are not considered has shaped the start-up sector here,” says the consultant quoted above.

Beyond the VC model it champions, specific allegations are hurled at Sequoia every time an investee start-up is in crisis: why did Sequoia miss the early signs of irregularity?

Like all stories, this also has two sides: the founder’s and the funder’s.

“The choice of how to run a company entirely depends on its founders. No matter how high the incentives of taking an unethical shortcut may be, maintaining high standards of corporate governance and financial controls is always the responsibility of the founding or management team,” says Aloke Bajpai, co-founder and group CEO, Ixigo, a travel app and Sequoia-investee company. A crooked mind bent on crime will always be ahead of those policing him, he adds.

Mahesh Singhi of the merger and acquisition advisory firm Singhi Advisors says that when malpractices in a start-up become public, investors find ways to escape responsibility. “In reality, the investor has absolute control over all operations from the MIS to which person to appoint and which direction to go in,” he says.

It is a familiar tale where some say it is difficult for investors to catch wrongdoing since they are dependent on quarterly reports sent to them by start-ups.

But when a VC firm of Sequoia’s pedigree is in the picture, questions will be asked if they have the wherewithal to spot a transgression. Sequoia in India and Southeast Asia is staffed with 11 managing directors and five principals in roles that take direct decisions on investments. However, the strength of the internal finance team that scans reports filed by investee start-ups is just six. In contrast, the team Sequoia has for human resource or communication is much larger, while the internal finance team is rather small for a VC firm that has close to 430 active investments in India and Southeast Asia.

Questions for the Shark

Geopolitics is in a state of flux, especially after the Russia-Ukraine war began, which, among other things, brought the West’s discomfort with China’s economic clout to the fore. It is widely believed that the US Fed tightening money supply led to the global funding winter in 2022, which made venture capital firms more circumspect as their limited partners started calling for action on investments.

The growing buzz around financial irregularities and corporate governance issues at its investee companies did compel Sequoia to take a step back and reassess matters. A clear indication of the corporate introspection became evident when it delayed the closing of the $2.8 billion fund in mid-2022.

Seemingly under pressure, Sequoia’s other managing director Rajan Anandan emphasised at the NASSCOM Product Conclave 2022 that the global funding environment had reverted to 2018–19 levels, with many VC companies shifting back to quality and viability of start-ups, with “pursuit of quality” topping their list.

When Sequoia enters a start-up, it immediately jacks up the company’s valuation even if its underlying value registers no great growth: a venture capital version of growth that ensures higher returns on investment but debunks all theories of creating a lasting business.

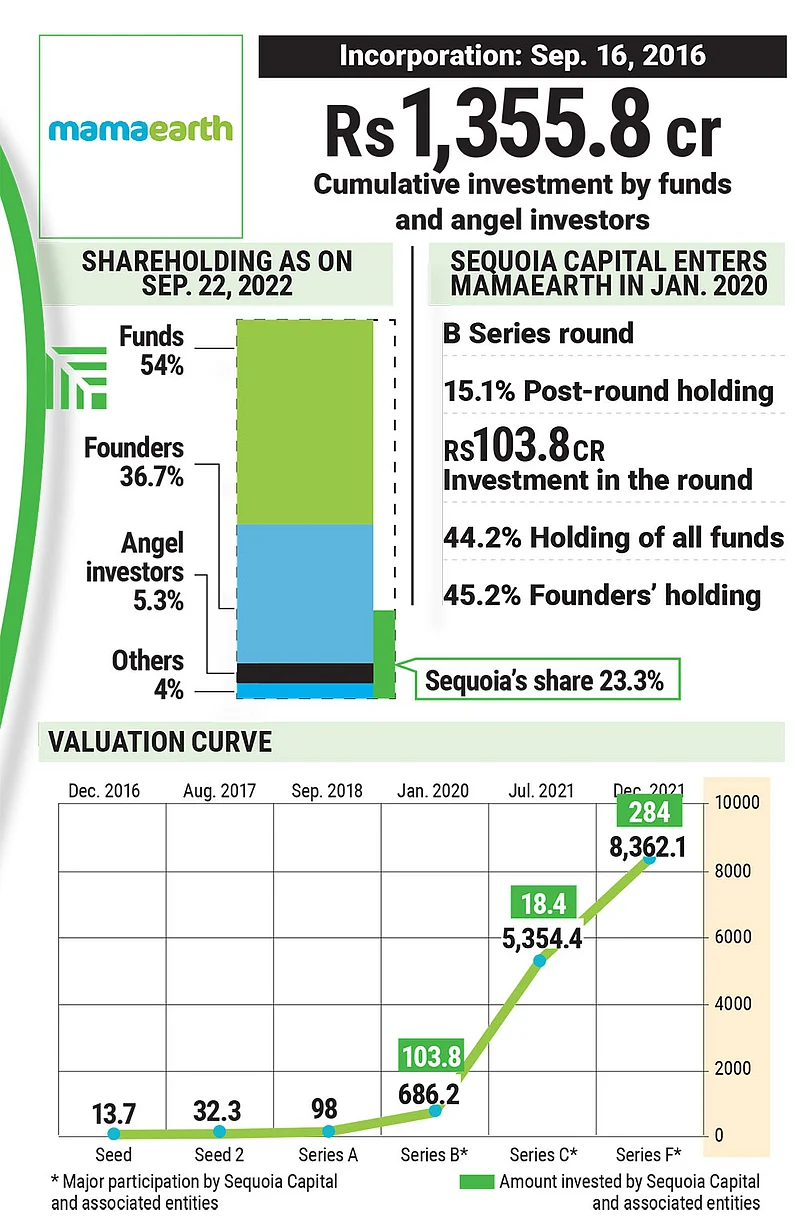

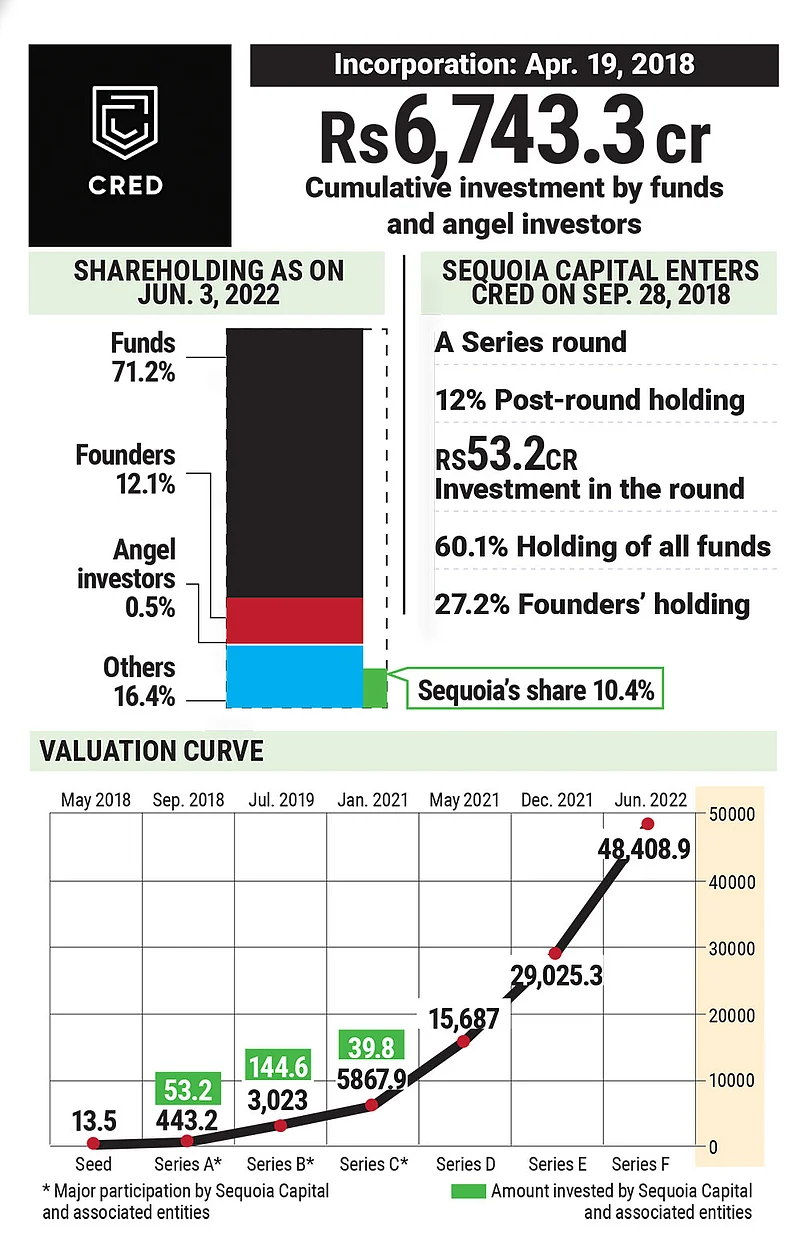

Take, for example, the case of CRED. Sequoia partnered with CRED in 2018 when the start-up was still new and was raising its Series A fund of $2.2 million. At the close of the round, the fintech company’s valuation jumped to $61.1 million from the seed valuation of $2 million. Sequoia supported CRED till the Series C round, taking its valuation to $805.5 million in November 2020. Similarly, Singh took Khatabook to a valuation of $600 million from the Series A to Series C rounds. Singh has been the principal investment advisor in both these companies.

Observers say that when Sequoia invests in multiple rounds in a start-up towards its journey to be a unicorn and beyond, it looks for two-to-three times jump in valuation. This observation is certainly true of its investment in Unacademy—another of those start-ups where Singh has been a principal investment advisor. Most start-up founders are chuffed to have Sequoia on their cap table. It has a ripple effect on the entire ecosystem, as, with Sequoia’s dollars in the kitty, a start-up begins to be branded as desirable.

“After speaking to many Sequoia-backed founders last year, I found a sense of overachievement and arrogance in them, the arrogance that since Sequoia invested in them, they were doing things right. Today, they are running around because their unit economics is not making sense and they are not generating enough revenue. Not one new investor is ready to invest in these companies,” says a co-founder and general partner of an upcoming, early-stage fund, which is rival to Sequoia.

Founders seem to be growing slowly with the realisation that the growth-at-all-cost approach, even when it is being advocated by the top VC firm in the country, has avoidable pitfalls. “Therein lies a problem,” says the founder of a fashionwear start-up. She tells us how she turned down a Sequoia cheque primarily because of the pressures it entails. “It is never about profitability, good practices, corporate governance and ethics. The founder of a profitable company is no more dependent on the VC money, so how will you bully her to remain on the treadmill of valuations?” she asks.

Course Correction

With questions about due diligence and corporate governance resonating across the start-up landscape, investors have belatedly decided to engage the big guns of forensic audit to shoot down the noise. The number of follow-on due diligence after investment by VC firms have increased as they commission consultants with experience in due diligence processes, like Kroll, EY and PwC, to take a closer look at their portfolio companies.

Saket Bhartia, managing director of forensic investigations and intelligence for Southeast Asia at the American corporate risk analysis firm Kroll, says that due diligence was done in the start-up space earlier too, but now its character seems to have changed. “A growing number of PE and VC funds are reaching out to us to enhance this with aspects like external reputational and proactive due diligence as well as portfolio analysis to raise potential red flags,” he says.

Interestingly, last year Zilingo had reportedly commissioned Kroll to investigate an “anonymous whistle-blower complaint” against Ankiti Bose, which looks like a case of a delayed response to a crisis that could have been averted proactively.

“Earlier, investors would call investigators quite late, as they themselves learnt about the issues very late. ... Now investors are increasingly doing active portfolio monitoring even where there are no real problems,” says Bhartia.

While the mantra in Sequoia is to trust unless confessions suggest otherwise, efforts have started to engage with their partner start-ups to instil best practices on the path to corporate governance. The number of follow-up due diligence has also increased.

“We do not want to penalise all founders for the mistakes of a few. Too much intervention would also obstruct normal every-day running of a business,” says a source in Sequoia. The VC firm has also started hectic search for independent observers to be placed on boards of their partner companies. The lookout is for credible names with experience of steering boards towards upholding corporate governance, hence the first choice are retired bureaucrats and technocrats.

“It is important to have a good, independent board of directors who are well qualified to advise on business matters. Such a board will act as a sounding board for management to run the business, give timely advice and ensure that public confidence in the enterprise remains high,” Mohandas Pai tells Outlook Business.

There are several things in question here: Singh’s way of working with founders and his team; how he is wading through the controversies that refuse to leave his side; and, how he is managing to keep his top bosses in the US invested in his leadership in India and Southeast Asia. “At the end of it, there is so much money at stake. Like in FTX, both Temasek and Sequoia said that the amount they had invested was less than a percentage of their assets under management (AUM). These cases [of Indian start-ups with financial issues] make no impact on Sequoia’s overall business or reputation, because the LPs think that it is less than 1% of AUM. So, who cares?” says a source close to Sequoia.

Well, some do.

“We are very early in our development as an ecosystem of start-ups and equity investing. Though the Indian ecosystem has grown fast, it still has to reach many levels of maturity,” says Padmaja Ruparel, co-founder of the Indian Angel Network (IAN) and founding partner, IAN Fund. A reputation loss at this stage of ecosystem development can spell doom for India’s ambitions for its start-up sector. This lends to demands for regulating VCs in India getting louder, followed by news that Sequoia’s honchos met the Central government representatives to ostensibly show support for a healthy and regulated start-up sector.

Focus has been on the indemnification clause in shareholders’ agreement between start-ups and investors absolving the latter of any culpability in case of non-business failures. While this is not unique to India, it disincentivises investors from paying attention to issues of corporate governance.

Catharsis

What is our tragic hero’s fatal flaw? It is energising Sequoia with hectic deal-making, say his fans; early success fuelling over-confidence, say his detractors.

But whichever version holds ground, the fact remains that Sequoia in India finds itself in troubled waters. Adding to the tension is the constant media focus on Singh. Sources close to him describe how disturbed he gets every time a story about him surfaces in the media. He calls them unfair.

A source in the VC firm, on strict conditions of anonymity, tells us about “mounting pressure since the BharatPe episode in 2021 to set things right”. He refers to internal questions being raised about why best practices around corporate governance were not instilled in investee companies and the extent of Sequoia’s knowledge about the goings on in a start-up when allegations of financial irregularities surface.

Sequoia is frantically trying to set the narrative straight by advocating building intergenerational companies with lasting leadership. But can it shut out the noise around Sequoia’s role in controversies in start-up after start-up?

Now that the Sequoia honchos have met key government officials, the former project it as an overture from the government to emphasise the role of the firm in creating wealth and jobs in India. But given the current sentiments against the VC firm, the government could consider probing the books of its investee start-ups which are either already listed or about to be listed at the bourses. If it results in a law that disallows loss-making start-ups to be listed, it could prove detrimental for the whole Sequoia bouquet in India and affect its reputation globally.

This story is far from over, but its high priest is not free of blemish anymore.

Note:

This story has been edited with a reference to Trell. The earlier version contained a mention to the result of a forensic report whose content is not publicly known.