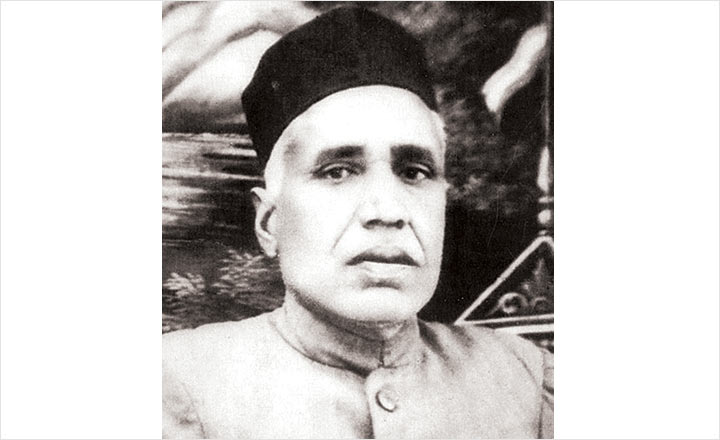

Jagannathji Goenka, my grandfather, was the eldest son among nine brothers and several cousins. His father was also the eldest son. Thus, dadaji became the de facto head of the extended family. Back in the ‘60s, there were over a hundred members in the household and while they were all engaged in businesses of their own, when it came to a family dispute, crisis or matrimony, everybody consulted him. He was my hero and till this very day is my greatest teacher.

He would carry along a pocket diary all the time and would jot down details of youngsters who’ve reached a marriageable age wherever, he went. Matchmaking was his favourite pastime. He even undertook measures to ensure every girl who received a proposal stood a good chance to be picked. So when a suitor would visit our home, he’d insist that no other girl more attractive than the one proposed to, be present.

He would carry along a pocket diary all the time and would jot down details of youngsters who’ve reached a marriageable age wherever, he went. Matchmaking was his favourite pastime. He even undertook measures to ensure every girl who received a proposal stood a good chance to be picked. So when a suitor would visit our home, he’d insist that no other girl more attractive than the one proposed to, be present.

With transport in those days not being as efficient as it is today, people would end up coming to our place in Hisar for a halt during their travel. Dadaji would ask me to massage the feet of the elders and I enjoyed the chore due to the entertaining nature of the conversations that transpired. When alone at bedtime, he’d narrate stories of the people he dealt with — their relationships, attitude and mannerisms. And that was my biggest source of learning as he would not deliver long sermons on life otherwise.

I was only 12 years old when he first assigned me the task of accompanying trucks ferrying our produce to nearby markets, where I was to collect money from the commission agents we catered to. Soon after that, I was allowed to travel to Delhi to oversee the grain trade along with Munimji and other employees. I enjoyed the trip that included a 5 am ride on the Krishna bus service and a return journey from Fatehpuri in Delhi at 5 pm that very day. This was followed by a ritual of tallying expenses where every penny was accounted for. There was one instance when dadaji asked me to note down the expenses for the day and not question Munimji about a Rs.15 charge for oil change. Since we didn’t use a vehicle for the journey, I asked what that was about only to learn much later that it was for his personal entertainment (a kothewali) as he was away from home for a long period. Dadaji was frugal with money but he was also a pragmatic man.

As children, we were not allowed luxuries such as watching a movie unless a guest or a son-in-law of the extended family was accompanying us. But Satya Narain and me figured out a way to enjoy a movie by buying one ticket for two days instead of two for a single show. I’d watch the first half on one day and he’d watch the second half, and the next day we’d swap. There was no way our absence would go unnoticed for three hours from either home or work and once in a while we had to face our uncle’s ire when we were caught. But dadaji would defend us saying, “Chhora kaam karey hai. Kya baat ho gayi agar picture dekh li (The boy is working already so what’s the harm if he watches a movie?)”

It’s unfortunate that unlike back then, my grandchildren don’t have time to sit and talk with me today. Maybe, I don’t have the time either to bring in that personal touch like dadaji. He was a wise man. The best part about him was that he never admonished me for my mistakes. He just asked me not to repeat them. If others complained about me, he’d say, “Gir ke hi seekhogey (You’ll only learn from your mistakes).”

He had a knack for reading people. I remember a visit to Hansi market yard, where dadaji had to recover money from someone. We met the person momentarily before he left for lunch and dadaji predicted he would return pretending that he’d eaten a hearty meal. And my grandfather’s guess was spot on. He explained that the man wanted to deceive us into believing all was well financially when in fact he was burdened with debt.

Apart from inculcating several life lessons, he was also one of my biggest supporters. When I passed 10th grade in 1965 with a good score, he approved of my admission to Punjab Polytechnic Institute in Sirsa. It was a big deal in the family as most patriarchs then preferred that their sons took over the reins of the family business. I felt liberated in college and those were fun days! The sole ambition of the boys at my college was to charm girls at the college next door; we all bought cycles to impress the girls but nothing went beyond just getting their address. Ram Singh and gang were great fun — they ate meat, got drunk and would party all night. I enjoyed everything else apart from the meat. We travelled to Bhatinda to watch a circus and that was the time we witnessed the prettiest site thus far — bikini-clad women. My roommate Radhe Shyam was my conscience-keeper; he dissuaded me from giving in to temptations.

***

I cried after reading dadaji’s letter. I was having a great time in college, I didn’t want to get back. But mid-way through second year, he wanted me to return as business was suffering and the family could no longer afford my education. Dadaji had placed some bets in Satta Bazaar and the price went against it. Plus a huge investment in an oil mill, financed through loans, failed to deliver. As word spread that our firm was unable to honour its commitments, arranging for working capital became tougher. The cash crunch was killing us; fitting in aptly with the proverb in our community, “Occhi punji, khasam ko khaye” (a cash crunch can kill a businessman). Business came to a standstill.

And when I returned home and saw dadaji, he looked like a man defeated. His was a commanding personality otherwise, but he was so weak then. The only question I had was — what next? He didn’t have an answer and he was of the opinion that we must let the storm pass. I disagreed. But he claimed nobody would help us out; he’d even buy lottery tickets in the hope that someday we’d win something. After six months, I was restless and confronted him about re-starting the business. He refused even then saying that there was no money to do so but I persisted and convinced him to let me revive our dal mill.

It wasn’t easy to win back the confidence of the traders. Even if my bid was high, they would ignore it to sell it to a bidder who paid a lower price. I felt humiliated. One day, a distant relative advised me to make partial payments to agents every few days from the sales cash collection. It worked like magic. And since I made the effort to go and hand over the cash proactively, gradually their faith in me was restored. As time passed, dadaji grew confident that we would tide over the difficult times. All through this period, I remember my mother telling us to believe in ourselves and in God. She was a religious person who managed the affairs of the joint family and not once did I hear her complain about having too much work. It was a year since we re-started the mill and I was 18 then. We managed to make a profit and save Rs.300,000 but the debt was not entirely paid off.

***

A bus ride from Hisar to Delhi altered my growth trajectory. I met Chaudhary Aman Singh, an assistant manager with the Food Corporation of India (FCI). As the official procurement agency of the government, FCI was a huge player in the grain market. FCI would procure grains, store it and then auction it to traders after a couple of years to be supplied to the open market. But the Indian Army, would not procure from FCI as it had stringent specifications that the government agency couldn’t fulfil. Instead, the food and agriculture ministry would float tenders for traders to supply to the army.

This is when I sensed an opportunity in the food grains trade and I made an offer to Singh. I suggested that we could purchase the stock from FCI and supply it to the army. It passed through various levels of hierarchy before the ministry awarded us a pilot project, with some incentive given to the officials involved of course. But it wasn’t a clear road ahead as traders, who formerly supplied to the army, tried their level best to put me out of business. First they tried to get my supplies rejected. When that failed, they lobbied to levy a tax on sales from outside Delhi. That would hike my cost but they clearly didn’t expect that I would move to the capital overnight. Moving away from home was a tough decision. I rented two mills, one in Nangloi and another in Najafgarh, both in opposite ends of the city and would end up spending almost the whole day to visit both of them.

Since I lacked funds, I partnered with a rival, C Lal, an influential trader who had the resources but lost the bid. He gave me the money and an accountant to run the business and we agreed to a 50:50 split of the profit. While that sounded like a fair deal, it was anything but that. After executing three contracts, we ended up with a marginal loss as opposed to my calculation of a Rs.300,000 profit. When I confronted Lal, he denied any foul play. But I had no way to prove him wrong, I was duped and I felt dejected.

My folks back home were sympathetic but they asked me to return to Hisar. I was back to where I started and I resented it. All efforts to convince my family to let me give it another shot went in vain. Not surprisingly, even at this juncture it was dadaji who stood up for me. He instructed me to go alone. It was 1970 and I was 20 years old with Rs.17 in my wallet. I was experiencing mixed feelings about my journey ahead but I was determined to make it big in Delhi.

***

Mangat Ramji turned out to be a very helpful man. He was our neighbour in Hisar and was a broker in Naya Bazaar. I lived in his shop once I was back in Delhi. I wanted to enter the grain trade but knew nothing about it except for my dealing with FCI, so I registered myself for tender bids under the family firm name just to give the impression that it wasn’t a one-man show.

When I went for my first bid, which would be held at FCI’s Chandigarh office, I discovered that there was a cartel at play led by a man called Anil Chanana. The modus operandi was not going below an agreed minimum price and then splitting the contract with whoever won the bid. So, I invited the assistant manager Tibana and his assistant, Gurdeep for drinks. That dinner treat came from the money I saved living in a government-run guest house instead of a respectable hotel. And with their help, I won the first bid and then a few more. Gurdeep would open my bid last and quote the lowest price and in turn I repaid both of them in either cash or kind.

Engaging in the grain trade was a turning point in my life. I managed to reduce the family debt by Rs.500,000 by simply focusing on repaying the principal. Dadaji taught me that was a better way out when you present a lender with the option of either forgoing interest and accepting the principal amount or wait longer for the dues to be cleared, most lenders went with the former; except for a man called Radha Kishan Kharakediwala with whom I cut a deal about paying the principal amount of Rs.50,000 and an additional Rs.50,000 simply to be returned later just to keep the interest from piling up. The money was never returned but I saved up on the interest due.

There were several other such instances where I never missed an opportunity to save or make a quick buck. One such instance was the day I became a taxiwala. Our landlord in Rajendra Place, Makhan Lalji, who was rumoured to be dealing in smuggled gold, was in a great mood one Sunday morning, when he came and offered me his car for a joy ride. My friend, Ramjas, and I drove down to Bulandshahr in UP, about 180 km from Delhi, for some work. En route we realised we were running out of petrol. We hardly had money to fill petrol, but there was an unusual opportunity in sight. There were a bunch of people waving down buses and trucks. I stopped and offered them a ride for a fee per person at the same time warning them that we were running out of fuel so they may have to push if we stopped. By the time we returned from Bulandshahr, we had made a neat profit of Rs.60. We celebrated in style with a quarter whisky and dinner at Moti Mahal in Daryaganj.

After mastering the grain trade, I ventured into selling grain covers — low-density polyethylene sheets to FCI. Here again I was tricked by a business partner, Rakesh Gupta, due to my dependence on him for capital. He went back on his word about an equal share of profit and demanded a higher percentage once we won the bid and threatened to pull out if I didn’t comply. So, I organised Rs.70,000 on my own and went ahead without him. I convinced a banker, Suresh Rastogi to lend me money based on a personal guarantee against the security I offered in the form of the tender document. That’s the time I truly mastered cash management. I’d persistently follow up with FCI for timely payment and convince Union Carbide, the raw material supplier to sell us sheets in small instalments so we could manage with minimum working capital.

Apart from a prudent approach to the business, we also outsmarted the system at times to overcome obstacles. For instance, once despite my best efforts to deliver 3,000 covers to FCI on time, we were short by 100. If we delayed that even by a day, we would have lost the security deposit of Rs.70,000. I couldn’t afford that to happen, and since we could not bend the rules, we went around it. New Delhi was the only delivery depot for FCI and from there the consignment would travel to other places. We found out from the clerk that the order was to be dispatched to Jodhpur. I had a cousin in the transport business and through him we placed a bid for the transport and bagged that contract. After sending the initial consignment to the depot on time, we brought the truck back to the godown, added 100 covers and the consignment was sent to Jodhpur directly. It was unethical, we delivered a few days later but nobody noticed it and nobody incurred a loss.

Even as business was doing well, my encounters with deceitful men continued. But I had become smarter about how to spot trouble early on and tackle it. This time, it was Chaggan Lal, my accountant and his assistant Om Prakash. This was in 1976. While preparing an FCI tender, Om Prakash was very eager to know the bid price, which I found fishy. Dadaji had taught me that if one were to look into another person’s eyes while speaking about non-business matters, you can learn of the person’s true intentions. I gave Om Prakash the rates, and asked him to seal the envelope and put it in the FCI bid box before 11 am the next day. The bid was to close at noon. Later that day, I made another bid, handed it over to an official in FCI and asked him to put it with a timestamp of ‘after 11 am, but before noon’, stating that this was my final bid. When the bids opened, the penny dropped, there was a new entrant, whose bid was lower than my first quote. I sacked Om Prakash, but retained Chaggan Lal with a warning as he had served us for many years.