The sweet and juicy story around the country’s only pure-play listed beverages company, Manpasand Beverages, has now left a big stain in investors’ portfolios. The Vadodara-based juice maker, known for its Mango Sip brand, has fallen from grace after its auditor for nearly eight years, Deloitte Haskins & Sells, abruptly ended its assignment with the company.

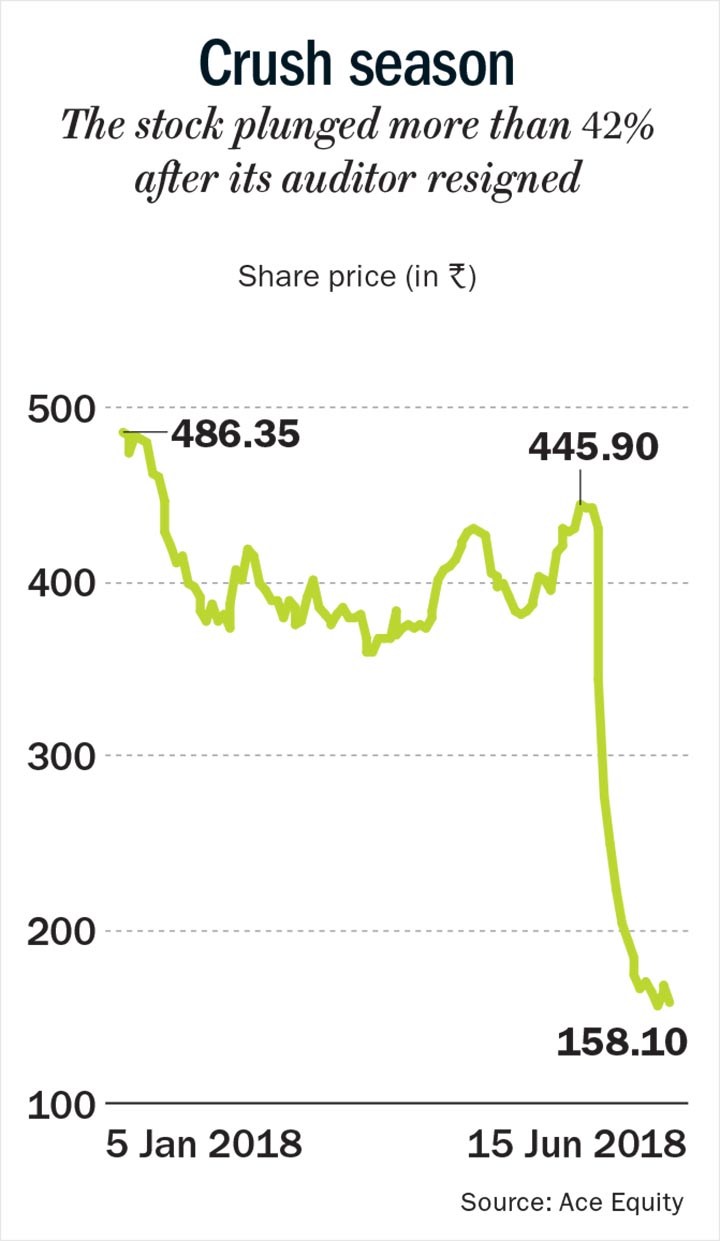

The stock, which listed three years ago, plunged more than 42% in just three sessions after the company informed the exchanges that its auditor had resigned just days before the board was to approve its quarterly and annual results. The stock is now trading below the issue price of Rs.160 (Rs.320 pre-1:1 bonus) at Rs.157 as of June 15. The stock had hit a high of Rs.512 in September 2017. With the stock hitting a new low every day, it has now been placed under additional surveillance by the exchanges with a daily 5% circuit limit.

While the company didn’t disclose the reason to the exchanges, in a letter to the Registrar of Companies the auditor has stated that the management didn’t provide “significant information” despite repeated requests. Though the company issued a statement terming the resignation “coincidental and a minor hiccup”, it’s yet to respond to a query sought by the stock exchanges; it did not reply to queries sent by Outlook Business either. This is not the first instance where there was a hiccup before the results were announced. In FY17, the Q4 result date was postponed from May 29 to June 13, a delay of 15 days. Incidentally, the results were announced without any qualification by the auditor.

Though the stock has less than a sensational debut after it fell below its listing price of Rs.320, over the ensuing years it caught the fancy of well-known institutional investors as the company showed some impressive growth and its founder, 55-year-old Dhirendra Singh found himself in the limelight as the media wrote extensively about his rags to riches story. While the twist in Manpasand’s tale was sudden, it wasn’t exactly unexpected given that in the past some market participants had raised doubts over Manpasand’s too-good-to-be-true story.

Sweet start

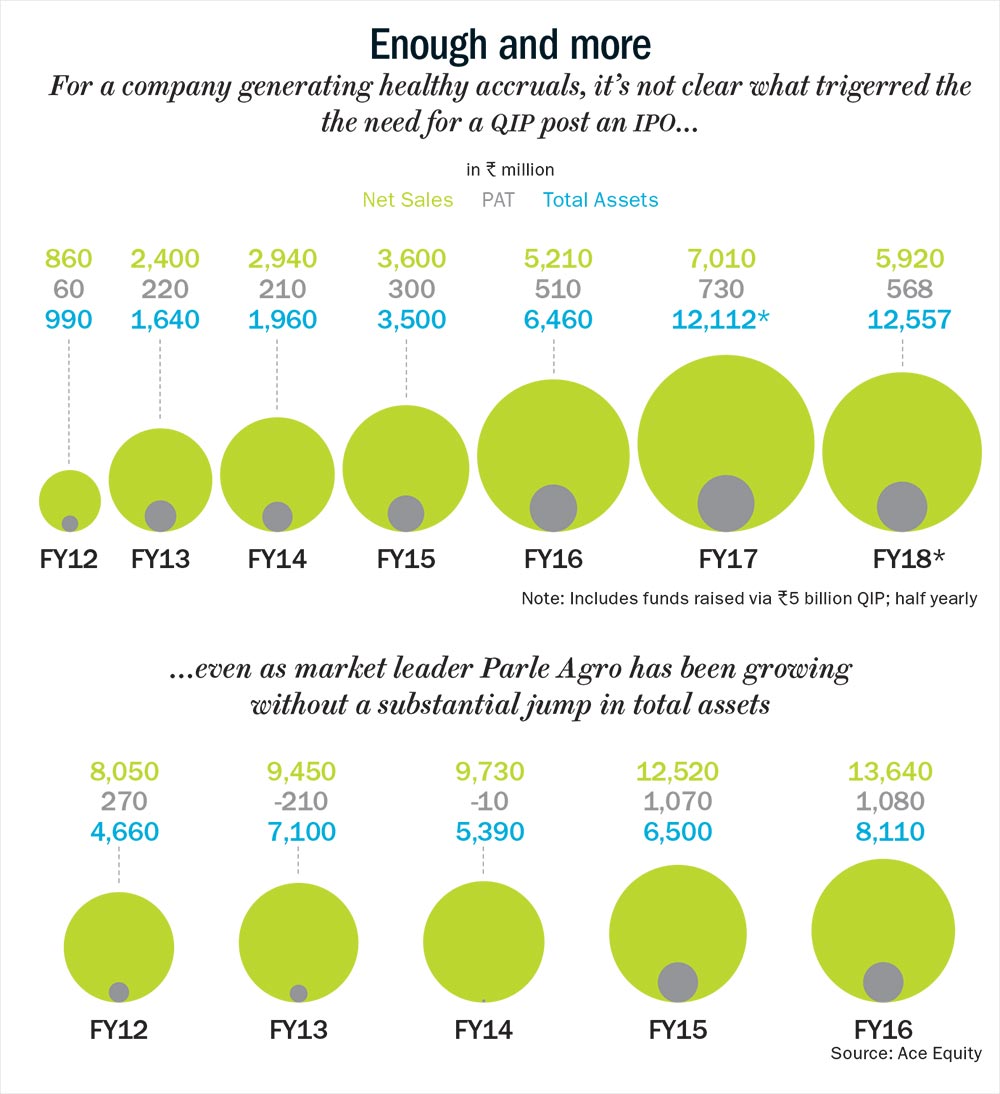

Manpasand operates in a category which has several established players such as Parle Agro, PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, Dabur and the likes. Mango juice dominates the fruit juice market with 85% share. After going public, Manpasand reported net sales growth of 44% to Rs.5.2 billion in FY16 and 34% to Rs.7 billion in FY17, while its rival Parle Agro, which dominates the market with its Frooti brand, reported net sales growth of 8% in FY16 to Rs.12.52 billion. In FY17, Manpasand reported PAT of Rs.730 million, up 43% while unlisted Parle Agro’s PAT was nearly flat at Rs.1 billion in FY16.

Having established a strong presence in the semi-rural markets, the company claimed that Mango Sip enjoys 10% market share and its FY17 annual report stated that the company was looking to substantially increase it beyond 25%. In fact, according to Euromonitor, the market research firm, the organised juice market had grown just 6.6% in volume and 10.2% in value YoY between 2016 and 2017. This meant that Manpasand was an outperformer as no other juice maker had reported such growth. Yet, Euromonitor’s top five brands did not feature Mango Sip. The company claims to have a footprint in over 20 states with over 400,000 retailers, 2,500 distributors and 250+ super stockists.

In December 2016, Amit Mantri, a fund manager at 2Point2Capital, wrote a blog post “The curious case of Manpasand Beverages”, questioning the company’s revenue growth and market share. In 2016, Mantri, like any other fund manager, was researching for a stock to invest in the beverage sector. “Manpasand operates in a sector which we think is very interesting. Beverage consumption is increasing, and this company has been reporting phenomenal growth. We were looking to invest in this space as there was massive potential for growth,” says Mantri. But during his research, he spotted big loopholes in the company’s growth story. “There was a huge mismatch between company’s revenue and growth of the industry,” says Mantri.

With Manpasand’s growth rate entirely differing from the industry, Mantri conducted a dipstick survey, speaking to more than 100 distributors in Tier-II and Tier-III cities. The survey revealed that Manpasand had a negligible presence even in its core market. “We found out that less than 10% of the retailers had Manpasand’s products. Some of them had put up hoarding of Mango Sip but didn’t even store the product,” says Mantri.

Mantri also punched holes in the company’s claims that it garners a significant portion of its sales from Indian Railways. “We couldn’t believe that they were generating so much revenue from Indian Railways. It wasn’t adding up. They had the approval to sell on only 3 out of 16 railway zones. A basic calculation showed that this was too small a market for the company to generate 25% of its sales,” says Mantri. “Mango Sip is only classified as a ‘Category A’ supplier by IRCTC while Maaza, Slice and Frooti are all classified as ‘Category A Special’ suppliers. This means that Manpasand is not allowed to sell its products on premium trains while competition can. Clearly, Manpasand’s competitors are better placed in selling on the Indian Railways,” mentions Mantri, adding that in the absence of a third-party ratifying the company’s market claim, there was always going to be a doubt.

Mantri wasn’t the only one. In fact, while Saif Partners was the earliest venture capital fund to invest $10 million in the company in 2011, IDFC Private Equity and Everstone, too, had evinced interest in the company. According to a source at IDFC Fund, during the course of their due diligence they found that Mango Sip did not command any visibility in retail stores in Tier-I and Tier-II towns except for railway stations. “We weren’t entirely convinced about the promoter’s response. Also, there was a lack of process coupled with a poor management information system. It was very much a one-man show. We were quite surprised as to how the company had managed to raise money from a well-known fund,” says the source. Not surprising that both the funds chose not to invest in the company. Incidentally, a year before Manpasand went public, Saif along Aditya Birla PE picked up additional stake by investing Rs.800 million in the company. In 2015, the company went ahead with its Rs.4 billion IPO by issuing fresh shares, post which the promoter’s holding came down to 50.4% from 67.2%, while SAIF’s around 30% stake came down to 22%, and Aditya Birla PE held 2.25%. Interestingly, in September 2016, Manpasand raised an additional Rs.5 billion through a qualified institutional placement (QIP) at Rs.716 a share. The funds were to be deployed for the company’s four new manufacturing plants having a total production capacity of 200,000 cases per day against the then 170,000 cases per day. The new plants with 50,000 cases per day capacity each were to be set up at four different regions — Sri City in Andhra Pradesh, Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh, Vadodara in Gujarat and the fourth plant in Eastern India.

Something’s amiss

For a company that generated over Rs.1 billion in profit over FY14 to FY16 and had raised Rs.4 billion through an IPO, the need for raising Rs.5 billion was a bit surprising, considering that the company could have funded the expansion through its internal accruals. Pointing out that Manpasand had used the part of the IPO proceeds to clear its debt of Rs.1 billion, Mantri questions, “If the company had around Rs.900 million in cash as of March 31, 2016 to invest in growth and expansion, what was the need to raise capital through equity? The expansion could have been easily funded by debt and internal accruals.”

What’s more disconcerting is that utilisation of existing plants have come off. At the time of the IPO, its capacity utilisation was around 60%, and now it has drastically decreased to 56%. “If the existing plants itself are not utilised then why are you spending money on new plants?” he asks.

But none of the existing investors were perturbed about these issues. Vishal Sood, managing director at SAIF Partners, told CNBC-TV18, the fund had done due diligence before investing in 2011 and 2014 but didn’t come across any trouble. SAIF, which had invested Rs.900 million, now holds 17.57% stake, after it sold over 2% stock in 2016 for Rs.670 million. Its holding which was worth Rs.8.6 billion before the crash, is now worth Rs.3.3 billion. However, despite a freefall in the stock price, the fund is backing the management. Motilal Oswal Mutual Fund, SBI Mutual Fund and ICICI Prudential Mutual Fund hold 5.51%, 4.40% and 1.04%, respectively. SBI Mutual Fund and ICICI Prudential Mutual Fund chose not to participate in the story. In a note to investors, Motilal Oswal stated that while it had done the due-diligence at the time of purchase, being a listed company, it had placed its faith on the audited numbers as it was backed by a widely respectable audit firm who were the auditors for over five years prior to the listing. It is now awaiting the results of the company along with the opinion of its newly appointed auditors, Mehra Goel & Company, before taking any action. For the nine months of FY18, Manpasand has shown a 28% rise in net sales to Rs.7 billion. Of the many brokerages that had a ‘‘buy’’ on the stock, most have either suspended coverage or are awaiting the management to come clean. But now that the seeds of suspicion have been sown, the stock is unlikely to be a market favourite anytime soon.