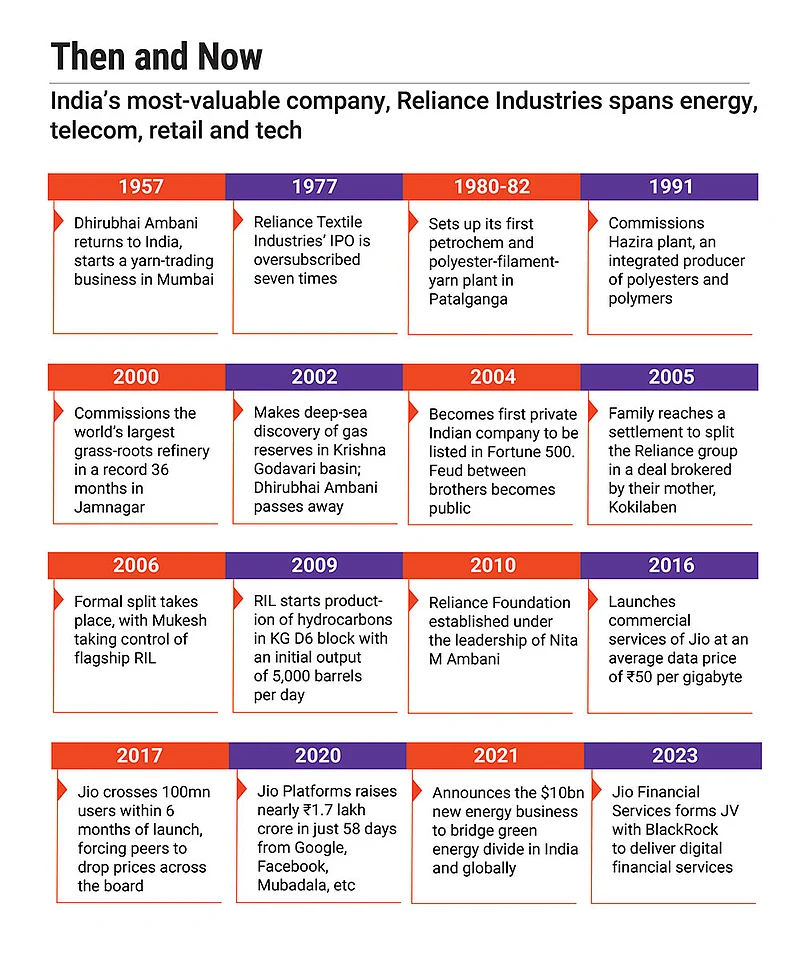

When Dhirubhai Ambani died in July 2002, he left behind no will, only an empire. At the time, the Reliance group boasted revenues of over $12bn which was over 2% of India’s GDP. But without a succession plan, the company’s future was quickly consumed by a storm of whispers and sibling strife between his two sons, Mukesh and Anil.

The feud, once private, spilled out into the open eventually. At its peak, the family drama roiled the Indian stock markets. So public was the dysfunction that then Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee was forced to step in, advising the brothers to resolve the dispute swiftly.

It was Kokilaben, the matriarch, who summoned both sons and, with the help of banker KV Kamath, forced a truce. Mukesh kept oil and petrochemicals. Anil took power, finance and telecom. However, the conflict continued for years after.

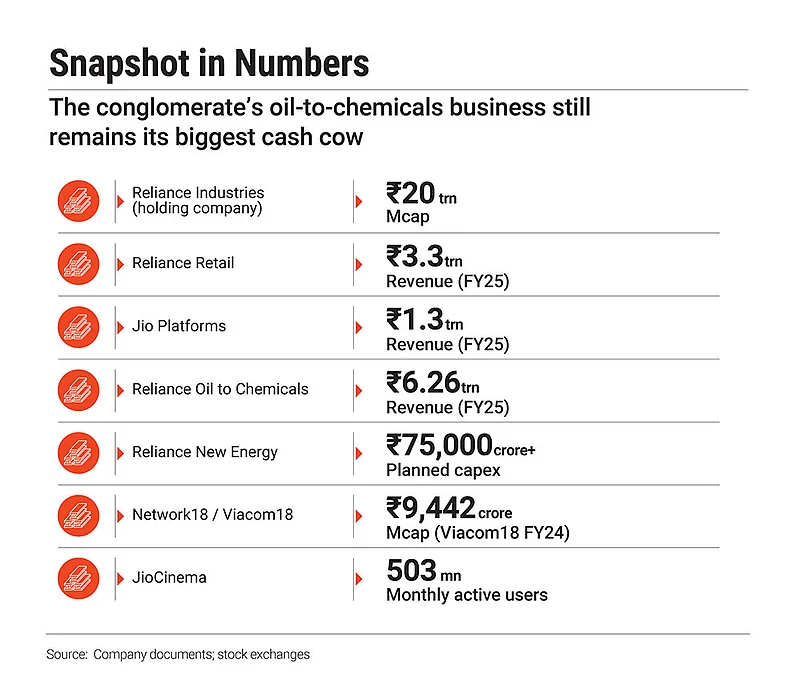

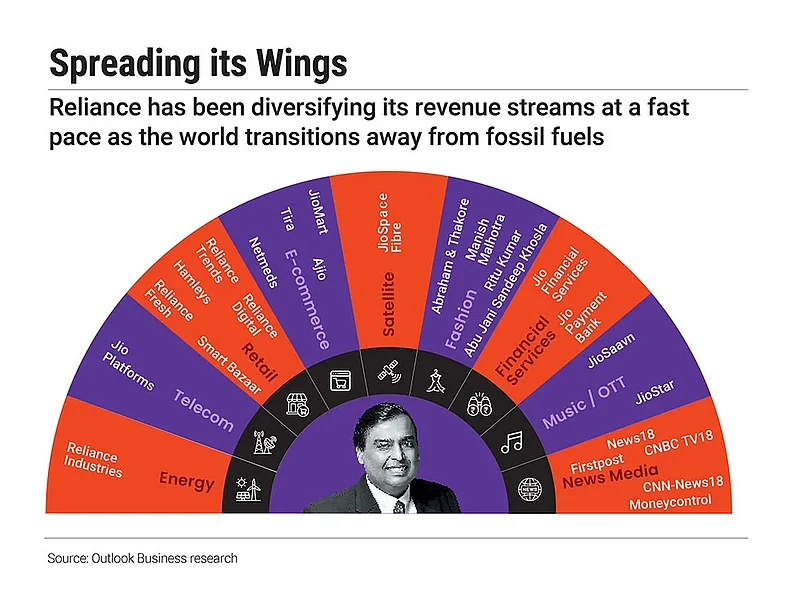

While inept choices have almost fully depleted Anil’s businesses since, the elder brother has expanded his empire and stomped his way into his sibling’s sectors after the end of a non-compete agreement. Reliance Industries (RIL), the holding company of the sprawling conglomerate that Mukesh has engineered, is now the most-valuable business in India with a market capitalisation exceeding $240bn (₹20trn) and commands the largest share, almost a tenth, of the country’s exports.

Today, as Mukesh contemplates a succession in his branch of the family, he wants to mitigate the chaos that unfolded two decades earlier.

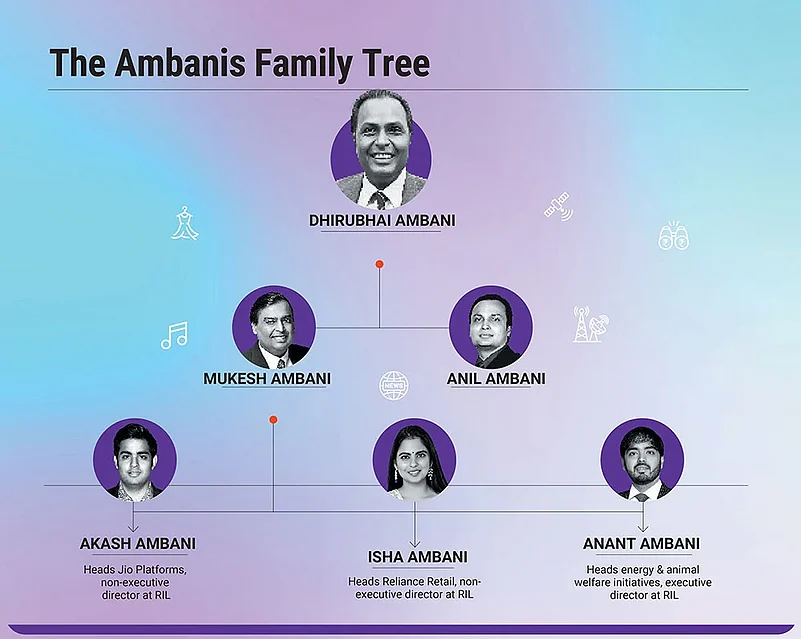

A few years back, he reportedly showed interest in the Walton family model, where the day-to-day management of Walmart was outsourced to professionals and the family just retained board-level oversight. However, it’s not clear if Mukesh has made up his mind on the matter as he has also positioned his children as leaders of distinct verticals: Akash for telecom, Isha for retail and Anant for new energy.

“The fact that the next generation is being groomed to take over is the right thing to do, rather than them being suddenly parachuted to the corner office one fine day,” says Shiram Subramanian, managing director of proxy advisory firm InGovern.

Choosing Their Stripes

Earlier this year, Nita Ambani, Mukesh’s wife and the chair of an $8.5bn joint venture between RIL and Walt Disney, said in an interview that the couple’s three children played a key role in succession planning. The scions chose which verticals of RIL they wanted to lead based on their own personal interests, Nita told Bloomberg.

Akash runs Reliance Jio and is driving its pivot from mobile connectivity to a full-stack digital infrastructure business. He oversees the group’s push into AI, enterprise cloud and undersea cable systems. Low-key and detail-oriented, Akash is viewed as a tech geek by family and friends.

Isha, Akash’s twin, is the only one among the trio with an advanced management degree. After graduating from Stanford’s business school, she worked as an analyst at management consulting firm McKinsey before joining the family business. “I will feel proud if someone says: ‘She furthered her parents’ legacy.’ And of course, if Reliance can be one of the top 10 companies of the world, that would be a dream come true,” she told Vogue in 2019.

Apart from leading the retail business, Isha also is the only one among the siblings to sit on the board of the conglomerate’s newly launched financial-services arm. She is also the only one among the trio to be married to a scion of a prominent Indian conglomerate that has interests across finance, pharma and realty, among other businesses.

Anant, the youngest, has taken charge of Mukesh’s latest bet: a $10bn investment in new energy. More spiritual and inward-facing than his siblings, Anant speaks the language of responsibility and legacy, often framing his work in terms of devotion and sustainability.

Challenges Galore

As the Ambani scions take over the business, it won’t be easy. They have to find avenues of growth in mature businesses and seek out newer verticals to keep shareholders interested, according to industry watchers. Most importantly, they would be expected to deliver at the same breakneck speed of Dhirubhai and Mukesh.

For Akash and Isha, the magnitude of the challenges has already started revealing itself.

“The private equity investors who invested billions of dollars in Jio Platforms and Reliance Retail are waiting to exit. Even though strategic investors like Google and Meta might have a longer horizon, the financial investors will seek to exit sometime via initial public offers [IPOs] to cash in on their returns,” says Subramanian of InGovern.

But RIL has delayed the IPO plans. The two verticals need to mature more before going public, so that the investors can secure bigger returns. On the back of $60bn of investments over a decade, Jio, led by Akash, has become the world’s largest mobile-data network by consumption with more than 488mn users.

However, everything is not sunny. The vertical’s monetisation has lagged due to a prolonged price war and its inability to make consumers pay for value-added offerings like media and financial services as yet.

“In India, tariff hikes are tough because value customers lack disposable income, and Jio, with a large share of them, struggles to drive revenue this way. Fixed-wireless access adds some upside but strains capacity 10–20 times more than mobile, limiting scale... If Vodafone Idea exits, Jio gains short-term revenue by absorbing its users, but long-term ARPU growth depends on premium customers—a segment where Jio remains weak,”

According to him, Jio’s real monetisation potential lies in premium 5G services, but its spectrum is too limited to allow top tier user experience.

Make no mistake. Despite these issues, Jio today controls 40% of the telecom market, with Airtel being second at 34%. As a result, according to analysts, Jio already accounts for the lion’s share of RIL’s valuation, trumping the older verticals of oil to chemicals and retail.

Moreover, brokerage firm Bernstein expects Jio to become the biggest contributor to RIL’s earnings before interests, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) by 2025–26.

On the other hand, experts say the fortunes of Isha’s Reliance Retail aren’t panning out so well.

As growth slowed down over the past few years, Mukesh has reportedly stepped in to fix things. Hundreds of physical stores have been shuttered, thousands of employees have been laid off and any new hire beyond a certain salary threshold has to be directly cleared by the patriarch’s office, according to Bloomberg.

While RIL is looking to list the entity at a $125bn valuation, multiple brokerages have pegged its value in the range of $50–90bn.

“The area that Reliance Retail has been falling short is customer experience. It is not a very difficult thing to crack as there are global benchmarks in retail—Amazon for online and the likes of Zara and H&M for offline,” says Arvind Singhal, a veteran management consultant.

He goes on to add that for most of its history, Reliance has been an industrial company rather than a consumer-facing one. Given that Reliance Retail is the country’s biggest retailer with ₹3.5 lakh crore of annual sales, it might be too late to fix the culture.

“It might be as difficult as trying to convert an oil tanker into a cruise liner while it is on sail,” quips Singhal.

Question of Cash Cow

One of the biggest reasons Mukesh Ambani was able to build RIL into the sprawling megastructure it is today was the steady, firehose-like cash flow from the oil-to-chemicals (O2C) business. For years, this legacy engine—refining, petrochemicals and fuel marketing—provided the capital muscle to fund RIL’s ambitious pivots into telecom, retail, and now, green energy.

“O2C’s integrated operations, flexible crude sourcing and consistent demand position it well to deliver stable cash flows. These flows are critical in supporting the company’s ongoing diversification into high-growth, capital-intensive areas like new energy and digital platforms,” says Vinit Bolinjkar, head of research at Ventura, a brokerage.

Anant has been entrusted with the new energy mandate. Though symbolically significant, it is still in the build-out phase; it may take years before it becomes cash-generating at a scale comparable to the Jamnagar refinery.

“While full profitability will take time, Mukesh Ambani has stated that these businesses could become as big and profitable as the O2C segment within five to seven years. This suggests a cash-positive outcome in the 2030–32 window, particularly as scale and efficiency improve,” adds Bolinjkar.

In context of the investment demands of the new energy bets, a critical question that arises is: can the retail and telecom verticals expect support from the O2C cash-generation machine in the long run?

It’s also worth noting that energy, specifically gas pricing and allocation, was at the heart of the feud between Mukesh and his younger brother Anil in the mid-2000s. That fight not only dented the Reliance empire but also triggered shareholder volatility and government intervention. As the next generation settles into their roles, the ownership and governance of the O2C vertical may be essential to avoid ambiguity and future conflict.

Future Tense

Morgan Stanley, an investment bank, recently estimated that RIL’s bets on AI and new energy could unlock $50bn in additional value over the next decade. But unlocking value is not the same as creating it, especially in a conglomerate where the past funds the future, and the future is arriving faster than the systems meant to manage it.

The Ambani scions are not just inheriting businesses, they are inheriting a national expectation. RIL today is not merely a company; it is a key part of the Indian economy, its capital flows, a force in policymaking and central to tapping the rising aspirations of the Indian consumer.

Mukesh’s children must deliver precision and vision without margin for error. They are expected to be operators, reformers, diplomats and futurists—all the while living under the shadow of a founder’s founder and a builder who rewrote the rules of Indian capitalism.

The empire is theirs. The machinery is live. The ambitions are public. But as the lines between private succession and public consequence blur, a simple question hangs in the air: can the heirs of the megastructure learn to govern it or will it be too big to handle for them?