It’s around noon in Thoothukudi, a district situated in the south-eastern part of Tamil Nadu and home to Sterlite Copper’s manufacturing unit at the SIPCOT Industrial Complex. In the sweltering heat, a truck bearing the number plate, TN 69 4235, trundles its way out of the plant. It’s a long journey ahead since the consignment is to be delivered at Sterlite’s unit at Silvassa, located at a good 1,700 km-plus from the southern state. Forty-five-year-old Shanmugham, who’s at the wheels, and his assistant, Murugan, know the route quite well but are also aware that the consignment is worth over Rs.1.5 crore.

After a break at Namakkal, the trucking hub of Tamil Nadu, the drive turns pleasant as the sun has set. Shanmugham switches on the headlights, illuminating the path ahead in a nice golden hue. The rumbling of the engine is the only sound that reverberates in the eerie stillness of the night, as the vehicle makes its way through the 463-km route from Namakkal to Chitradurga (Karnataka), a dense and treacherous stretch known to be unsafe for drivers. It’s closer to midnight when Shanmugham notices a vehicle trailing his truck. Assuming it to be just another passenger vehicle, Shanmugham continues to drive till he notices that the vehicle instead of pulling ahead is still trailing it. Anxiety grips him as he recollects tales of how consignments were stolen and drivers who resisted ended up paying with their lives. Fearing the worst, he steps on the accelerator, but the 21-tonne load doesn’t let him pull ahead. That’s when things begin to turn ugly. The trailing vehicle suddenly picks up speed and comes perilously close to the side of the truck. His worst fears come true as he notices four people with sickles and knives, directing him to stop the vehicle.

Instead of putting up a resistance, he calmly presses a switch adjacent to the steering wheel. The goons force the vehicle to a halt and push the driver and his helper out of the truck. One person takes control of the vehicle, while the rest stay in the jeep. Bruised from the fall, Shanmugham is not too worried about losing the truck. The switch he had turned on was a fuel cut-off device, which would soon immobilise the engine after travelling a few kilometers. As luck would have it, he comes across a police patrol vehicle and informs them about the hijack. Hopping on to the vehicle, the patrolling unit travels a good 5 km, when they notice the flickering tail light of the truck at a distance. Nearing the vehicle they notice that it’s stationary and no one seems to be in sight. Shanmugham is happy that the device had done its job and that the consignment is safe.

The above incident is part reality and part fiction but what is true is that such a technology does exist and has been deployed by Sterlite Copper on all its long-haul vehicles to prevent such incidents. For the over Rs.22,000-crore company, which meets 48% of the country’s copper demand, relying on cutting edge technology had become the need of the hour. N Hariharan, head of logistics, Sterlite Copper, says, “Implementing the device has eliminated robberies as in the past we have lost over Rs.4-5 crore worth of goods and not to mention the excruciating procedure of lodging a police complaint and doing follow-ups. It’s a huge loss of manpower.”

The company behind the device is the Navi Mumbai-based Novire Technologies, which has built a suite of products aimed not at just preventing theft but also ironing out the fault lines in transportation and a company’s supply chain. Uma Rajan, co-founder and partner, Novire, says, “It’s a customised solution that we have created for Sterlite wherein a 24/7 control monitoring room both at Namakkal and Bengaluru, not only tracks the trucks on a GPS network but also ensures that the company doesn’t incur any monetary loss. Our role is to act as a revenue enabler besides bringing in efficiency into the logistics network,” says Rajan.

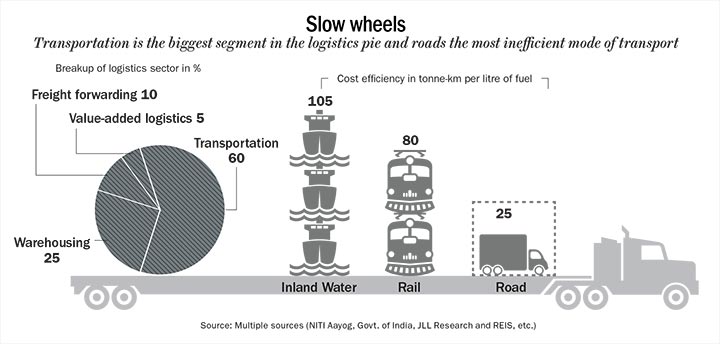

It’s not without reason. Efficiency is not something one associates with India’s logistics sector given that its inefficiency costs the nation 14% of its GDP. Reports suggest that the country can save up to $50 billion if logistics costs are brought down to 9% of GDP. Within transportation, which accounts for a huge chunk of the logistics pie, it is the road network that corners 57% of the goods transported by volume. This is despite the fact that in terms of cost efficiency, roads are the most inefficient and costliest mode of travel for domestic freight (See: Slow wheels).

Logistics major TCI along with IIM-Calcutta had conducted a study that revealed some telling statistics. Poor road conditions, check-post delays and old vehicle fleets resulted in trucks covering a maximum 250-400 km as against 700-800 km in developed countries. While a truck in India covers anywhere between 60,000 and 100,000 km in a year, in the US the travel time is 4 times that of India’s upper limit. The report pegged an annual loss on account of the delay at $5.5 billion. Similarly, the report states, additional fuel consumption owing to stoppages and slow speed of vehicles are robbing the economy of Rs.600 billion ($12 billion) every year. The biggest culprit for this loss are the inter-state check-posts across the country’s 29 states.

Hence, it’s not surprising to hear Nitin Vaidya, group manager, IT, VRL Logistics, griping about the huge operational hassle that the check-posts pose to the country’s largest fleet owner, which owns over 4,300 commercial vehicles. “While our entire operation is paperless we have one dedicated department tackling paperwork related to road permits. Kerala is the worst check-post where it can take over eight hours. In Karnataka, you have to show papers both at the entry and exit. It adds to the delay,” he explains. The same is corroborated by a World Bank article that states that exporters from manufacturing hubs of Tirupur and Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu divert their shipments several hundred kilometres to avoid the Tamil Nadu-Kerala border crossing. On an average, a five-hour halt at each border is a day added to a cargo journey between Delhi and Mumbai, the country’s two great economic hubs.

Putting this in perspective, TCI Express CEO PC Sharma elaborates, “A consignment from Delhi to Bengaluru takes four days and it has four states to cross. One inter-state check-post takes anywhere between three to six hours and that could stretch longer in case their servers are down. So that means 20 hours have been lost in transit, which otherwise would have yielded the vehicle one more trip.” The company, which works on an asset-light model, has 1,600 vehicles on the long haul (long distance) and an equal number on the network (short distance), that is, from the customer’s place to the nearest TCI branch.

Hariharan of Sterlite shares a similar take. “The minimum distance our truck goes is 700 km in three days and the maximum is 3,400 km in 10-12 days. Within 700 km, the truck may have to halt at one check-post, which could be a couple of hours. But longer the distance, you can imagine the loss of time not just from a delivery perspective but also loss of business for the trucker.”

But what is now par for the course is expected to change from July 1, with India switching over to the most awaited indirect tax reform in the country since independence.

Burning rubber

The implementation of Goods and Services Tax (GST) is expected to result in a common market, thereby allowing unhindered movement of trade across state borders. A consumption-based tax, GST will be received by the state in which the goods or service are consumed and not by the state in which such goods are manufactured. The GST will be administered in three forms: CGST, to be paid to the Centre and SGST, to be paid to the state and, in the case of an inter-state sale, IGST will be applicable. That’s a sea-change from the current system of differential tax rates prevalent across states. As a result, check-posts at state borders scrutinise each and every consignment for material and location-based tax compliance, thus stretching transit time by several hours. In addition, officials of different state and central agencies such as transport, VAT and forest departments also have the authority to stop vehicles and check for relevant documents. This is despite the number of vehicles detained for non-compliant documentation estimated to be less than 1%.

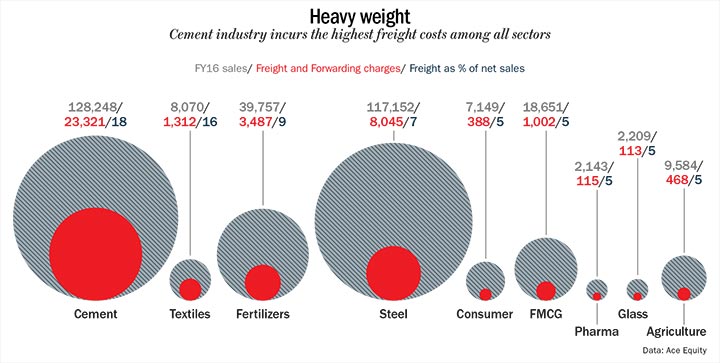

Incidentally, over the years, freight costs for most sectors have kept increasing and, currently, it is cement and other weight-heavy commodities that bear the biggest burden. FMCG and consumer durables are sectors where freight costs are comparatively lower but still a good 5% of annual sales (See: Heavy weight). Britannia Industries, the country’s biggest biscuit player with over 35% market share, incurred over Rs.431 crore in freight expenses in FY16. “While we are waiting for the final contours of the GST in terms of tax rate, we have been working on getting GST-ready since the past eight months. But, I believe transportation will become more efficient and turnaround time will be faster,” says Varun Berry, managing director, Britannia Industries.

For the over $4-billion Godrej group with business interests ranging from processed food to FMCG, real estate, appliances and agriculture, the advent of GST couldn’t have been more timely. Group patriarch Adi Godrej says, “Once GST comes in, tax evasion will disappear and government revenues will rise considerably. I believe GST can add 1.5-2% to the GDP growth.”

Though the model GST law does not provide any clarity on the removal of check-post related compliances, Godrej believes otherwise. “There will be considerable savings in logistics since there will be no hold-up of trucks at state borders as it happens today. There is no doubt that under the new regime, outposts will become irrelevant.”

Loading up

It’s not just big corporates which are awaiting the imminent arrival of GST. A lot of buzz has been created within the logistics space, especially on the transportation side with a whole host of start-ups mushrooming over the past couple of years to make the most of the opportunity coming their way. Rivigo, an aggregator with 2,100 trucks, is less than five-years old and has raised over $114 million from a clutch of investors. Deepak Garg, founder of Rivigo, says, “With GST coming in, corporates would want faster transportation and to address that need we have created a unique 24/7 fleet through a driver relay system.” Harnessing the power of big data, the driver of a Rivigo truck will hand over the truck at a particular pit stop to another driver, thus saving on time and addressing the issue of driver fatigue. In doing so, the company ensures drivers get back home the same day or within 24 hours and, thereby, save 50-70% of the turnaround time on long-haul routes.

While players such as Rivigo are deploying their own patented algorithms, independent players such as Novire are adapting to the GST regime by making their technology available to a diverse clientele comprising the likes of Vedanta, UltraTech Cement, ACC, Asian Paints, HUL, and Coca-Cola. “Our GPS enabled technology can easily track the travel time, distance travelled and the time lag to complete the journey. Our clients have gained anywhere 20% and 50% in turnaround times,” says Rajan. Sterlite Copper, which has 300 trucks on its network, has deployed Novire’s technology on a cost-sharing basis. The company, the transporter and the truck owner each incur 33% of the cost. “That comes down to Rs.400 per vehicle for the owner… that’s a win-win for all stakeholders,” feels Hariharan of Sterlite Copper.

But given that India’s transportation sector is largely unorganised and fragmented, some chronic challenges still remain.

When size matters

“Times change. Some things don’t. Coca-Cola” reads the backside of Umesh Madhyan’s card. The tagline promotes the world’s oldest carbonated drink, but the national head of infrastructure and logistics at Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages, the bottler for Coke in India, is looking forward to change of a different kind. “Single-touch logistics is good for the product, since you don’t handle it multiple times and the customer gets it faster and cheaper. Today, we lack a transporter who is truly national. The regional dominance of most truck players is because the laws don’t allow one state’s transporter to do business in another state,” says Madhyan, whose company owns 24 bottling plants in the country. For example, a truck registered in Bengaluru can deliver to Tamil Nadu. But after delivering the load, the trucker can’t scout for business within the same state. “In that sense, a trucker’s capacity is restricted,” points out Madhyan.

About 90% of vehicles in India are owned and operated by individual owners having one to three vehicles. And because of the fragmented nature of the sector there are no defined regulations governing size and capacities of trucks. “There are 720 dimensions of truck bodies plying on the roads. A cement company wants 22 ft, the transporter makes a 22-ft truck body and if his next customer is a fried chips manufacturer who wants 30 ft, the same is converted into a different specification. Overseas it’s defined in pallets – there’s a six-pallet truck and then a 12-pallet or 24-pallet vehicle. The Central Motor Vehicles (CMVR) Act should lay down clear guidelines,” adds Madhyan. But given that in the whole discussion around GST, there has been no mention of an amendment to the CMVR, it is unlikely Madhyan’s concerns will be addressed anytime soon.

What might not change by design could change by default, post GST. Priyajit Ghosh, partner, indirect tax, KPMG, believes that with GST and the road infrastructure improving in the country, the tonnage capacity of trucks will increase and that could lead to some standardisation. “Currently, trucks travel 200 km a day, but if you have good roads, and few big warehouses, post GST, it can travel 300 km.” And it looks like logistics players are considering a change. Blue Dart, the country’s largest domestic express freight company, which has over 1,000 trucks plying on the road, is considering increasing tonnage. Yogesh Dhingra, COO and CFO, Blue Dart, says, “We would be doing some reengineering based on both improving road infra and a change in the warehousing segment.”

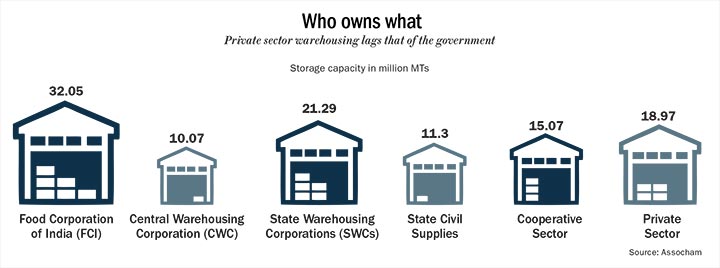

Indeed, warehousing is yet another segment in the logistics space that is going to see quite a bit of action in the coming days. Currently, it’s the government and not the private sector that owns a chunk of warehousing capacity in the country (See: Who owns what).

Tipping the scale

In the current scenario, a manufacturer has a warehouse in almost every state since goods sold outside the state of origin are liable to levies such as excise, customs duty and central sales tax, which are not credited back to the manufacturer. This, in turn, adds to the cost of a product unlike goods sold within a state wherein the value added tax is credited back on inputs. Hence, most manufacturers maintain separate warehouses and show the transfer of goods as one between inventory and stocking points within states. In other words, the warehousing footprint in the country is designed to save on taxes rather than achieving operational efficiency – not to mention the additional cost incurred on storage. Garg of Rivigo points out, “Now, you don’t have to be present in every state. GST will incentivise a pull-based supply chain rather than a push-based one.”

Concurring with Garg, KPMG’s Ghosh says, “Since you are not required to make sales from each of the locations, warehousing will consolidate, resulting in economies of scale.” Dhingra of Blue Dart believes companies have the opportunity to pursue need-based warehousing. “From a count of 30 warehouses, it could go down to five or six big warehouses. As transporters, we would do more km per day, thus reducing costs and reaching the customer faster.”

Manufacturers can now look at a hub-and-spoke service delivery model wherein strategically located centralised warehouses can cater to demand coming from a clutch of states. In doing so, companies can enjoy economies of scale achieved by cutting down on variable costs, relying on automation and, in turn, improving operational efficiency. Godrej says, “Currently, we need to have depots in every state to avoid sales tax and reduce CST, which will now not be necessary. Deliveries can go straight from our factories to the distributor.”

Though most of the depots are on lease, Godrej mentions that given the peculiarities and imperatives of different businesses, a radical consolidation in warehousing is unlikely. Currently, group flagship Godrej Consumer Products has 20 facilities spread across far-off locations such as Baddi in Himachal Pradesh and Puducherry, besides its biggest unit in Malanpur in Madhya Pradesh. Though a majority of the units is in the North East, the management believes the benefits of the excise tax holiday in the region far outweigh the cost of logistics.

Britannia, too, has over 80 manufacturing units – of which 14 are in-house and the rest are outsourced along with 45 warehouses. Echoing Godrej’s views, Berry says there won’t be a dramatic shift in its warehouse footprint. “The only constraint that will prevent us from reducing our warehouse footprint is that we have a very light product and the volume to value ratio determines our freight rate. For Rs.1,000 worth of products in HUL, the company would require a very small space whereas for the same we would need a lot more.”

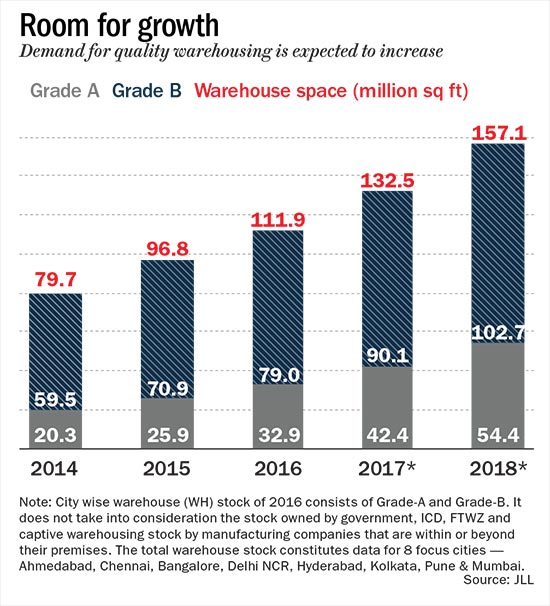

While sectors such as FMCG will be more concerned about being closer to the market, there are a whole host of sectors that don’t need to be spread out. Real estate consultant JLL estimates that the country’s total warehousing space requirement in the top eight markets will grow from 111 million sq ft to 157 million sq ft by 2018 (See: Room for growth). Not surprising that logistics and even real estate companies are keen on cashing in on the opportunity. For example, the Bengaluru-based Embassy group has formed a joint venture with Warburg Pincus with a commitment to invest $250 million in building warehouses across the country.

Anshul Singhal, CEO, Embassy Industrial Parks, says, “Currently, companies don’t bother about the quality of warehousing so much, because it’s only for billing purposes. But the minute you change that, you need a good quality developer, and you want the warehouse to last 10-15 years. There is great demand for grade-A warehouse supply, which will flourish from next year.”

Embassy is building seven big warehouse-cum-industrial parks around major metros and cities. “We are not building standalone warehouses but gated community warehousing facilities with common infrastructure such as roads and power. We are building on land parcels of 50-100 acres, which can accommodate six to eight buildings,” informs Singhal. While the company’s Chakan warehouse is already under construction, the Mumbai and NCR warehouses are in the land acquisition stage and the Chennai warehouse is in the approval stage. Between seven cities, the plan is to create 15 to 20 million sq ft of warehousing space.

Adarsh Hegde, joint managing director of Allcargo Logistics, too, has a sense of the changing pulse. “Warehousing models will change. Against the past trend of picking up 10K-15K sq ft in different states, players can opt for 50K sq feet in fewer locations. By doing this, they will have better negotiation power as well. So warehousing charges will come down,” he predicts.

Allcargo, which manages close to 200,000 sq feet of warehousing space, too, is looking to scale up. “We have identified locations where we need to be. In some warehouses, we have the capacity to expand further,” he adds.

Given that the country faces a shortage of Grade A warehouses, established players such as logistics giant DHL Supply Chain, part of Deutsche Post DHL Group, had in 2013 embarked on a euro 100 million investment plan to develop multi-client facilities across the country. It currently has 7 million sq ft across 160 warehouses in 50 cities.

Vikas Anand, managing director, DHL Supply Chain, India, says, “Sectors such as auto, technology, and MNCs, which have a mindset of outsourcing, will be first one off the blocks to consolidate and outsource their warehousing requirements. But large industrial houses or very large MNCs, which have been managing logistics in-house, will see how things play out before jumping in.”

The juiciest gain that a consolidated warehouse footprint offers is that not only will companies save on storage charges but also on inventory costs. Garg of Rivigo says, “GST will disincentivise inventory creation in the economy. Around $100 billion of capital is stuck, ranging between two months and six months of inventory. Now, companies can survive with less than a month of inventory and that is a big unlocking for a country like India.” While that may indeed be the case, Anand believes companies will play it by the ear rather than getting swayed by the benefits of a so-called unified market. “Given that the cost of capital in India is upwards of 10%, there will be gains accruing from consolidated inventory but companies will still be worried as they wouldn’t want to miss out on a sale as the customer could end up buying some other product,” explains Anand.

While that could be a reason for some to abstain from aggressive downsizing of their warehousing presence, companies such as Britannia also attribute it to the challenge that secondary transportation or the last mile network poses. While quite a few start-ups are acting as aggregators for unorganised trucking players, the closure of some start-ups is also causing concern. “While we are working with a couple of start-ups in Hyderabad, you don’t want to end up engaging with a contractor who commits a position but is unable to sustain operations because his funding has dried up. So, you have got be careful and watchful,” mentions Berry, who though expects Britannia to shut a couple of warehouses.

Even smaller companies with less than Rs.500 crore turnover such as House of Anita Dongre are not factoring in any major inventory gains. Currently, if a company ships a good from Mumbai to a store in Delhi, 2% excise sales tax is paid on the MRP and sales tax is incurred only at the time of sale. Post GST, for a transfer to any place outside a state, the company still has to pay GST and take one-time credit. Ganesh Babu, CFO, House of Anita Dongre, says: “I would have paid GST in advance but that benefit only kicks in when the sale happens. I will still have a one-time working capital requirement. Even for a company of my size, it means an additional working capital of Rs.20 crore. So, the reality is that one time working capital requirement is not going away.”

Good till it begins

Though the excitement around GST is palpable, it’s still early days on what gains and efficiencies India Inc will finally get to see. Sitting out of his 8th floor office at Andheri in suburban Mumbai, RS Subramanian, country head, DHL Express India, referring to the group's diverse presence across different logistics verticals says, “We are four men [referring to four vertical heads] standing on different sides of the elephant [GST]. So I can answer what I see…there is a stated vision [of a unified market and common tax rate] but then there is a ground reality.”

The biggest change that DHL Express, which deals with export and import parcels, is that earlier it was under the service tax ambit and now it finds itself entwined in the state jurisdiction as well. “We were completely central because of service tax now we are also liable to the state...that is one complexity to watch out for,” says Subramanian, whose company earns 70% of its revenues from SMEs.

The other complexity that GST has thrown up for the transportation sector is by keeping petroleum products outside its ambit. Fuel accounts for 60% of the cost in transportation business. Hence, its exclusion would result in additional costs and disrupt the chain of credits in GST. But Garg is optimistic about the opportunities that lie ahead for in the transportation space. “We are not just solving a business problem, but also uplifting the quality of life of truckers in the country,” he says.

Any financial gains accruing through operational efficiencies will always be welcome for India Inc. While Berry refrains from pinpointing the potential gain, Godrej expects GCPL could incur an annual saving of Rs.20-30 crore. For now, DHL’s Subramanian believes the priority for everyone would be to just get GST compliant as transacting business with a supplier or customer without a GST registration number is out of question. “It’s an enormous change for anyone and a huge learning curve for everybody. Expect sleepless nights for six months, but if it still continues after six months I will be worried,” sums up Subramanian.