Pithampur, an industrial hub in southwest Madhya Pradesh, is known as the ‘Detroit of India’. Here Darshan Kataria has been running a pharmaceutical unit since 1991. The MD of Vindas Chemical Industries, he is today baffled by the many warrens and procedures of Goods and Services Tax, or GST, introduced in 2017. “We have a refund pending from July 2017, relating to an export transaction. We have no clue where to go to get that cleared,” he says.

He believes that GST has hurt small businesses like his. Pithampur, otherwise known for large automobile original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) such as Volvo Eicher, CASE Construction, Force Motors, Bridgestone, and Mahindra Two Wheelers, is also home to around 50 pharma units.

Kataria’s business has come down from Rs.250 million in FY14 to a fifth of what it was. And he is barely able to utilise 20% of his export-oriented unit’s capacity. He can’t attribute this downfall solely to GST though. “Our export destinations such as Yemen, Syria, Iran, Iraq and Latin America have seen civil wars and financial trouble over the past four years. Also, our big brothers in pharma, who faced stringent restrictions in the US market, started dumping products in emerging markets, making things hard for small exporters like us,” he says.

India might have improved its ranking on World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business metric but Gautam Kothari, president of Pithampur Audhyogik Sangathan, a local industry body, believes GST has left SMEs uneasy. Kothari runs a drip-making unit in Pithampur and also happens to be a chartered accountant. “I see two faults with GST. First, it is penalty-based, rather than incentive-based; second, the accounting. Two companies, one with sales of Rs.100,000 and other with Rs.100,000,000 are expected to maintain similar records. While the big guys have the bandwidth to do this and also don’t deal with unregistered suppliers, small and medium players find compliance tiresome,” he says.

The small players are also now dealing with overcautious banks, which have become so after the rising number of defaults. “Banks are very conservative in dispersing loans to us now. Economy runs on risks and this wariness is taking away our risk-taking capacity,” says Kothari.

Away from Kothari’s office in Indore, workers are busy working with auto parts at Kach Motors’ plant in Pithampur. Kach supplies U-bolts, shifter rails, kingpins and shafts to OEMs inside and outside Pithampur. Puneet Gupta is the director at this plant founded by his family in 1997 as a steel processing unit. In 2004-05, they entered the auto-component space. “Our initial performance was appreciated by Eicher Motors. So they gave us more business. Today, we are making more than 500 parts,” shares Gupta.

The past year has been good for Gupta. From Rs.550 million in revenue for 2017-18, he is expecting to finish the current fiscal with Rs.750 million. While passenger-vehicle OEMs such as Maruti Suzuki India, Hyundai, Tata Motors and Renault India have stayed away from the cluster, Gupta still thinks there is an advantage to manufacturing here. “There is no trouble with power supply or industrial relations, and land is more easily available,” he says. While automotive clusters such as Gurgaon-Manesar have seen fierce unionism and labour violence in the past, Pithampur has remained a trouble-free oasis.

Then, why have major OEMs stayed away from this region? Gupta believes it has to do with access. “Places such as Pune, Chennai and Sanand have easy port access and a well-developed vendor base,” he says.

Lack of effective connectivity with ports has been a longstanding issue in this cluster. Currently, the rail connection with Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust (JNPT) in Mumbai is a long and indirect 830-km route whereas a direct link can bring this distance down to 580 km. To this end, Indore-Dhar-Chhota Udaipur project was sanctioned way back in 2007 but, even after a decade, the progress has only been 10%, in distance covered, according to Kothari. “Between 2008 and 2018, the project cost has also gone up 3x, since new land acquisition rules came into effect in 2013,” says Kothari. Compensation for acquired land has gone up by 3x to 4x.

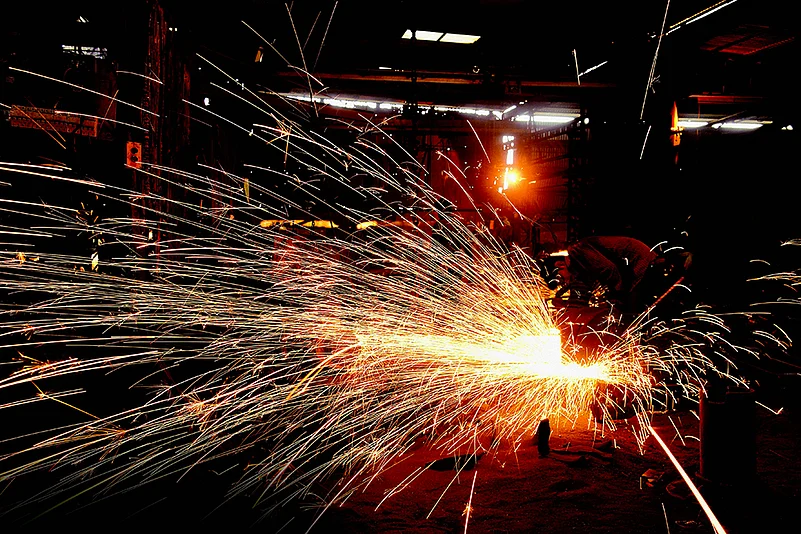

In 2018, a new rail line between Indore and Manmad was also sanctioned. It may still be time before industry sees a more efficient rail link here, but there are units which are already benefitting from government’s increased investments in rail infrastructure. Raneka Industries has a massive shed inside their plant at Pithampur. Being a steel foundry for making wagons, the factory has an old world charm to it. One can see large steel tubs pouring molten steel into the casts. Workers are bent over the wagon wheels, sharpening their ridges with saws, spewing sparks. The final products are bogies and couplers.

“Our customer is Indian Railways. Business has been good because of government’s increased thrust on railways,” says Kapil Jain, managing director, Raneka Industries. From Rs.420 million last year, the company is going to clock a turnover of around Rs.650 million in the current year. “Our order-book is looking good for the next six to eight months but future growth will be dependent on the new government’s policy on railways,” says Jain. Majority of their supply goes into freight wagons.

Jain is appreciative of the outgoing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government’s policies for the industrial area, and hopes the new government will maintain the momentum of growth. His is a power-intensive industry. “Till 2000, we suffered from massive power shortage in this area. This was eventually resolved by the government in 2003 and we have never since faced that crisis afterwards. On a unit basis, at Rs.6/unit, power is still cheaper than in Gujarat and Maharashtra,” says Jain.

Availability of water has also been problematic in Pithampur, particularly in the summer months. Raneka Industries’ plant consumes between 600,000-700,000 litres per month. But with the Narmada project near completion, the industry is hopeful that water availability will improve.

Labour Trouble

Minda SAI, a well-known auto component player in the country, has a harness plant in Pithampur. It caters to Volvo Eicher, the largest truck/bus manufacturer here. When we reach, we see workers testing spirals of harnesses on high-end machines. Even in commercial vehicles such as trucks and buses, electric parts are becoming more important with each passing day.

Minda SAI is already preparing for BS-VI emission standards. During our interaction, we learn that a few of the executives on the floor are ‘visitors’ like us. It is not unusual for people to travel from more developed auto component zones such as Gurugram, Pune or Chennai to Pithampur for better pay or through transfers. Often, the best talent and the well skilled are not available nearby.

But even more surprising is the lack of unskilled labour. Many unit owners blame social welfare schemes for this. “My workers don’t want to accept bank transfers because that might deprive them of their below-poverty-line (BPL) status. Also, many social scheme beneficiaries do not want to work in factories,” says a unit owner. Jain seconds this. “The labour pool is shrinking here and we are a labour-intensive unit. We are loaded with orders but are unable to fulfill it.”

Kothari feels skill development is a challenge in Pithampur. “Government has skill-development schemes and gives grants up to Rs.5,000 to every underprivileged student. Yet, we see a lot of dropouts from the skill-training programme.” It is a problem faced by almost everyone in the industry. Kach Motors’ Gupta, who is part of the MP government’s skill-development programme, shares, “To solve our problem, we have tied up with engineering colleges to hire apprentices.” He is also experimenting with robots/automation in his new plant. “It is collaborative tech, we are not replacing people,” says Gupta, who is looking to scale up.

Like Gupta, others in the cluster are trying to leverage tech to boost sales. Second-generation entrepreneur Tahir Raza, 26, is seated before a computer in his office. Outside, trucks are being loaded with thermocol boxes which will be used for packaging by industries in and out of Pithampur. “Most of our clients are from pharma and electronics sectors. We have seen a 25% growth in business last year and are going to do around Rs.80 million this year,” says Raza. Interestingly, offline plants are fast integrating with online opportunities — 15% of buyers now contact Raza online, via portals like IndiaMART. “Three years ago, we were selling nothing through online portals,” he says.

Shifting Gears

Raza’s buyers may be new but the automotive industry in Pithampur dates way back to 1989. It was lured by the central location and tax incentives. Among the first to set up plant here was US-based CASE, the construction equipment major. It manufactures loader backhoes and compactors. After starting out from Pithampur, CASE set up base in Noida in 1997, and in Chakan only last year.

Shalabh Chaturvedi, head of marketing, CASE New Holland Construction Equipment, says connectivity continues to be a challenge with Pithampur/Indore. “While air connectivity has improved, train and road connectivity are not up to the mark since Indore does not fall on the circuit of main hubs such as Pune, Delhi and Bengaluru,” points out Chaturvedi.

Now the cluster may fall short of funds too. “Only a few months ago, the Madhya Pradesh government decided to transfer locally generated funds and decision-making powers from our local Audhoyogik Vikas Kendra and vest them in the central agency in Bhopal. Earlier, the taxes/fees collected here were spent in Pithampur. This shift in power will lead to more bureaucracy and poor targeting of funds,” says Kothari.

The lack of road connectivity has not deterred Minda SAI. Its COO, Vaikuntam Srinivasan, says, “Our philosophy is to set up plants closer to the customer so that our engineering teams can service them. The cordial industrial relations at Pithampur are just a cherry on the cake.” Minda SAI runs a unit dedicated to Volvo Eicher and Srinivasan knows that other auto-component vendors won’t come in, as competition, anytime soon. No major passenger vehicle OEM has invested in Pithampur. “Unless there is scale, which comes with multiple OEMs, components players are not going to bear the pain of setting up base here,” says Srinivasan.

Case Construction has overcome vendor problems with the promise of assured volume. “We have spelt out a roadmap on ROI to attract our vendors here. I would say 50-60% of our parts are made within 100 km now,” says Chaturvedi. The construction industry is seeing good days thanks to the government’s investments on road building. “We are using 85% of our capacity and have grown by 20% during the last year,” exults Chaturvedi.

Perhaps, none of the large companies are facing any trouble with compliance or negative demand from GST, unlike their MSME counterparts. But there is still an unmistakable sense of optimism in this cluster that things can change for the better soon.