At Roca’s plant in Bhiwadi, workers are busy giving faucets a final silvery finish. Roca Bathroom Products is a sanitary ware major, with global sales of $1.75 billion. Having set up its faucet plant in Bhiwadi back in 2000, the plant employs 324 people currently. ROCA’s India operations contribute about 7-8% to global sales. “2017 was the most challenging year for our industry,” says KE Ranganathan, managing director, Roca Bathroom Products, sounding like a soldier who is thankful that the war is over. The construction sector, which directly determines demand for sanitary ware, took a beating due to the introduction of several structural changes like demonentisation, RERA (Real Estate Regulatory Authority) Act, and GST. “Conventionally, a lot of cash had been floating in this sector, which got hit by demonetisation,” he says.

GST also took a serious toll on the business. “Ours is a very trade-dependent business. We have 15,000 shops retailing our products but 70% of them didn’t even have an accountant. They had been operating like this for the past 50 to 60 years,” says Ranganathan. With so many retailers, the transition to GST was tough for Roca. They organised training sessions to prepare traders for the new tax regime. Now, things are settling down.

That is pretty much the story of most businesses in Bhiwadi. The industries in Bhiwadi, a town in Alwar district of Rajasthan, started clustering in the 70s after the government created an industrial zone, closer to Delhi. The town of Bhiwadi is located at the border of Rajasthan and Haryana, 80 kms from the country’s capital. Sajjan Kumar Agarwal, who relocated his stainless steel strip making unit from Delhi to Bhiwadi, 23 years ago recalls, “It was closer to Delhi, land was cheaper, and power situation was also good.” There are around 25 stainless steel strip makers today in and around Bhiwadi.

Seconds Ranganathan, “When we set up in 2000, the attraction was proximity to Delhi and good availability of labour.” Today, there are more than 2,900 big and small industrial units in the cluster. Ironically, infrastructure and connectivity issues continue to be a bottleneck at a time when companies are keen to exploit the opportunity to freely access markets across the country in the post-GST scenario. Business, meanwhile, is not in the pink of health but businessmen are hoping for a better year ahead.

Tough times

Some distance away from the Roca factory, Ram Prakash, the founder of Ratan Engineering has two units which manufactures engineering tools and dyes for large companies, automotive OEMs and also supplies tools to other tool-makers. Like Ranganathan, he, too, feels that the year has been tough. “We have been reading about the increased spending on infrastructure etc, but it hasn’t spilt over to us yet. Probably we are not in that league,” he says with some cynicism. Demonetisation and GST badly affected him during the year.

“In FY17, we did a business of Rs.25 crore. So, in the beginning of this fiscal, we were hoping to do Rs.30 crore to Rs.32 crore taking a natural growth of 20% into account.” Ratan’s business depends on how many new models are introduced by auto OEMs. “We make dyes for new models. We did badly in the December 2017 quarter—we barely managed to do 50% business of a normal quarter,” he laments. “We offered a better and innovative technology to clients in our machine tools business. Had we not done that, we would have not even done 50% of last quarter’s sales,” says Prakash. However, he feels the January-March 2018 quarter will be better as GST-related troubles will be over.

It was only two years ago that, Prakash cracked OEMs such as Maruti. “It was rigorous. Maruti flew us to Japan to benchmark with their suppliers. Only after that, they let us supply to them and their other suppliers,” informs Prakash. He feels that ‘Make in India’ is creating a positive pressure on OEMs and that augurs well for SME units like his. “They are increasingly trying to reduce imports and develop a supply chain in India,” he says. Price competition in the Indian auto market is also forcing OEMs to localise more than ever.

As electric vehicles are gaining popularity around the world, Indian entrepreneurs are steering in the same direction. Jeetender Sharma, who worked with Honda two-wheelers in its product development and marketing team, quit the company in 2014 to start his own electric scooter start- up called Okinawa Scooters. He set up a plant in Bhiwadi, attracted by the good supplier base for auto components, and started rolling out e-scooters/bikes in January 2017.

Sharma believes electric is the route to take even in two-wheelers. “Earlier, the speed, range, and power of available options weren’t good enough. We commenced with an 88 kmrange model Ridge in January 2017 but our latest product Praise can do up to 200 km on a single charge. Top speed is 70km/hour,” says Sharma. The two-wheelers are priced at par with their petrol counterparts, costing between Rs.57,000 to Rs.60,000. Okinawa currently has the capacity to make 300 vehicles per day and has managed to sell 5,000 two-wheelers in the first 12 months.

Stumbling blocks

Barring the odd new business like that of Okinawa, Bhiwadi is largely a cluster of traditional businesses – it is also an ageing cluster, especially Bhiwadi zones I and II. RIICO (Rajasthan State Industrial Development and Investment Corporation) which is responsible for acquiring and developing industrial areas, has developed two new areas in Karoli and Tatarpur as there are no industrial plots left in the old Bhiwadi I and II zones. But the grouse is that internal infrastructure like roads and drains are not well maintained, creating a connectivity barrier for industries.

Bhiwadi happens to be around 6 km away from National Highway-8 which connects Delhi to Jaipur. There has been a longstanding demand to build an elevated corridor, which will connect this industrial area with NH8. But that hasn’t seen fruition. The result is transportation delays, be it passengers or freight. While most factory workers live in and around Bhiwadi, the executives and entrepreneurs mostly commute from nearby Gurgaon, which can be a two-hour journey, one way, in peak traffic for a distance of 42 km.

TC Bhatt, regional manager of RIICO which is responsible for the development and upkeep of the industrial areas says, “The region is surrounded by Haryana from three sides and the connectivity issue with national highway has to be decided at national and state level. In past couple of years, we have improved roads inside the area.” Bhatt acknowledges that maintaining infrastructure in the old areas, such as cleaning drains and roads, has been a challenge but now cleaning has been tendered out to agencies.

The cluster also has law and order issues, feels DVS Raghow, honorary secretary, Bhiwadi Manufacturers Association and proprietor, The Sheetla Abrasives. “The area should be converted into a district to get more police force. There are frequent crimes like material theft, mobile snatching, car and bike lifting. The offenders commit crime and disappear,” he informs.

Ratan Chhabra, who runs Rashi Enterprises, a melamine crockery maker, echoes the same. “Iron moulds and dyes have been stolen from our plant frequently. Police often end up marking such cases as ‘non-traceable’ at the end,” he says. Chhabra runs a 40-50 worker plant and supplies to retailers. His business peaks during Diwali and New Year, so the firm wasn’t affected much by the introduction of GST. Chhabra shifted his factory from Delhi to Bhiwadi in 2003 due to the Supreme Court’s order of shifting polluting industries out of Delhi.

Since then, things have probably worsened. While RIICO and industry associations are working closely, there seems to be a need for more dialogue between industry and authorities. “It seems government is not bothered about the problems of industry. On Feb 29, 2016, Central Pollution Control Board introduced a new classification for pollution emission. Rajasthan Pollution Control Board hasn’t adopted the new classification, inspite of several representations. “CPCB has changed classification of industrial units based on emission of pollutants. So, all businesses need to revisit their compliance and some of us might benefit from the revision,” says Prakash. Separately, NGT issued a directive to suspend operations in 118 factories in Bhiwadi as they failed to obtain a fresh consent from them. These units had been operating without obtaining requisite permission from RPCB. On the directions of NGT, power and water connection of these units were disconnected. Industry feels that the suspension of operations may cause loss of jobs and production. “These are mostly smaller factories who are unaware of new regulations. We are working with them to ensure environmental compliance,” says Raghow.

Ray of hope

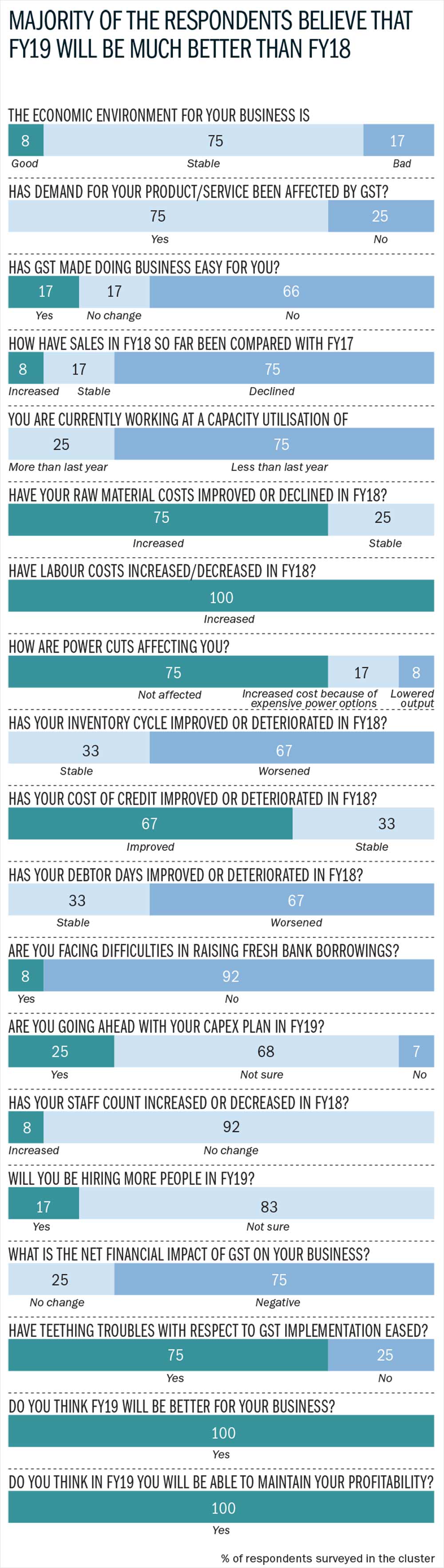

While GST seems to have disrupted business badly in the past year, companies are hoping for a better year ahead. 75% of the businessmen surveyed in the cluster said, the economic environment for their business was stable. While they expect FY19 to be a better year, they are concerned about increasing labour and raw material costs.

While that may turn out to be true, commodity producers did not make hay either. Agarwal’s single steel strip unit churns out 200-400 tonne of steel per month. “Our sales declined by around 10% over the past year because of GST as traders were not prepared for the transition and business was affected for a few months,” he says, without revealing the actual sales number.

More than rates, what’s been choking businesses is the impact of GST on cash flows. “GST sucked out a greater portion of working capital from businesses here,” says Raghow. However the teething troubles of GST implementation are slowly fading into the background. Prakash is planning to invest Rs.2.5 crore to increase capacity as he is hopeful of more orders from OEMs next fiscal. Most entrepreneurs, though, feel GST has had a negative effect on their businesss.

The only saving grace for now is that demand is expected to bounce back. Ranganathan of Roca believes that “residential realty, particularly affordable housing sector can drive demand in the future. We look at 2018 as the year of revival. The volume isn’t much yet, but we are exporting even to China,” smiles Ranganathan. One would only hope that demand revives to the extent that demonetisation and GST woes become a distant memory.