The significance of the Aam Aadmi Party’s (AAP) sweeping victory in the assembly elections is disproportionately greater than the smallness of Delhi as a union territory since the elections foreshadow India’s political future — most political contests are now likely to be between the Centre-right (in the form of the BJP) and a Centre-left option (likely to be a regional party). The Congress’ increasing irrelevance as a popular political force in most electoral contests will have an important bearing on how all the other political parties behave.

The BJP’s success in contests of this format (that is the BJP versus centre-left regional parties) is likely to be more mixed than its trouncing of the Congress over the past 12 months have suggested, as such contests underscore three weaknesses in the BJP construct even if the AAP had just won a simple majority instead of winning 67 of the 70 seats on offer.

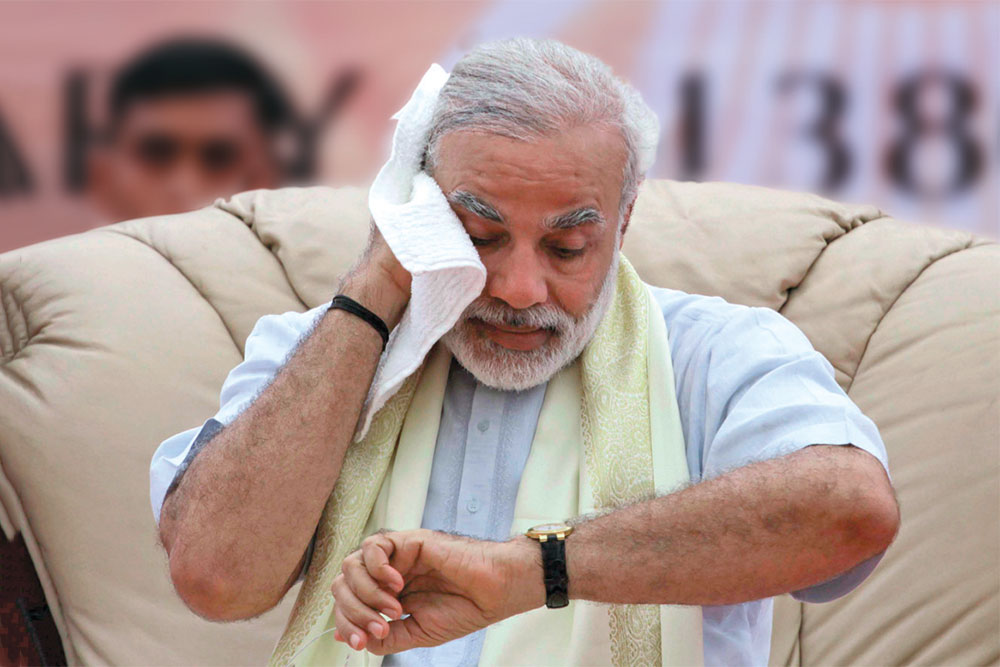

- The lack of credible leaders beyond Narendra Modi: The BJP lacks credible leaders (beyond Narendra Modi) who are trusted by the Modi-Shah combine. In Delhi, where the BJP has a core support base and where the party has held power before, the fact that it had to parachute in an outsider such as Kiran Bedi speaks volumes about the Modi-Shah duo’s lack of options among the traditional BJP leadership in Delhi.

- The lack of a cohesive value proposition for the working classes: The BJP’s appeal to the middle class and to the trader/merchant/bania community paradoxically makes it harder for it to mount a convincing appeal for working class votes. In states that are relatively prosperous (Maharashtra and Gujarat), this is less of a handicap, as the politics of aspiration seems to work in these states. However, in poorer states such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal (all of which go to the polls over the next 18 months), the BJP will have its work cut out. The Congress’ rapid descent has meant that the valuable political real estate is vacant on the centre-left in India and a whole gamut of regional parties will enthusiastically try to fill that space.

- The inability to articulate to the public at large the case for economic reform: Neither before the general elections, nor after it, has the BJP made an attempt to articulate to the broader public a case for economic reform in India. As a result, as the months go by, the BJP’s tactic of rolling out their main man for every election campaign is yielding diminishing returns. The party desperately needs to find some substance in its messaging if it is to win votes for anything other than Narendra Modi’s charisma.

RSS ideologue KN Govindacharya captures the BJP’s problems better than any sell-side analyst, as mentioned in an article published earlier in a prominent

financial daily: “Senior Sangh ideologue KN Govindacharya feels that for dealing with a state like Bihar the BJP will have to change its image and policies. ‘The party has to develop an image of being pro-poor. Its policies of late have contradicted that, which will affect its chances in a poor state like Bihar. If it really wants to appeal to the people there, it has to change its land-acquisition

policies and show itself as pro-farmer.’

The Delhi assembly elections reflect the need for parties to understand the local needs of people and not vague promises, Govindacharya added. ‘In Bihar, the BJP will have to address the problems of migration. Their social engineering methods have to be in interest of the people there, to win their trust. Their methods of relying on booth management or one person’s charisma will not work.’”

Investment implications

As highlighted in the model portfolio that my colleagues at Ambit published the day before the election result, while we are still overweight cyclicals, we are cutting our overweight in cyclicals by another notch. The Delhi elections reinforce my conviction that India is in the middle of a traditional post-general election economic recovery rather than at the beginning of a new Modi-led epoch.

The Delhi setback for the BJP will not only buoy non-BJP regional leaders in Bihar (slated for assembly elections somewhere between September and December 2015), UP and West Bengal (both of which are set for assembly elections next year), it could also have significant implications for the BJP’s economic policies. In particular, there are three significant implications which will give investors food for thought:

First, the BJP could now get pushed towards to the same sort of largesse (in terms of subsidy outlays) which was seen in UPA-II — government spending rose at a CAGR of 13% in the ten years that UPA-II ruled India. In particular, it seems likely that the Union Budget on February 28 will contain concrete proposals for subsidies on low-cost housing and on health insurance (alongside a big step-up in Government capex on T&D, freight corridors and roads, defence and railways). My colleague and Ambit’s Economist, Ritika Mankar-Mukherjee, believes that the fiscal slippage of 40 basis points looks highly likely in FY16.

Second, the BJP has been explicitly urging state governments to push forward land and labour reform at the state level. Furthermore, at the Centre, in early January, the BJP promulgated an ordinance to amend the UPA’s Land Acquisition Act. The BJP’s ordinance (which has not yet been tabled in Parliament) says that for projects which are in the “public interest” (for example, industrial corridors, public-private partnership projects, rural infrastructure, affordable housing and defence) consent from local people is not required. My meetings in Delhi suggest that even people within the RSS and policymakers are surprised at the political audaciousness of this ordinance. If the RSS’s hand is strengthened by the loss in the Delhi elections, it is possible that the NDA could throttle back on this push for land and labour reforms.

Third, in our meetings with investors over the past six months, we have been repeatedly asked whether Modi’s ascension signals a new epoch for India, one in which the country grows at a stretch for, say, ten years. Our response has been unequivocal — all the data available suggests that we are in the mid of a typical cyclical economic recovery of the sort India witnesses every decade or so (usually after a decisive General Election result). In the first three years of such a cyclical recovery, the Sensex typically compounds at around 35% per annum. Then, as the government loses steam due to corruption, inflation and political setbacks, the rally fizzles out and over a decade-long economic cycle the Sensex delivers 17% per annum.

Despite the concerns, I am still positive on the Sensex with end-March 2015 target of 30,000 and end-March 2016 target of 36,000. While my colleagues at Ambit are staying overweight cyclicals, in our latest model portfolio, the cumulative weight of defensives

(that is, consumer staples, IT and pharma) has moved up to 27% against 18% in our July 25, 2014 portfolio (and against 32% in the Nifty).

The writer, who has also authored Gurus of Chaos: Modern India’s Money Masters, has no financial interest in the stocks mentioned in this column