Yesterday’s (March 1) announcement by President Trump of imminent tariffs on steel and aluminum imports was taken poorly by global stock markets. Perhaps in an attempt to convince investors this was an incorrect response, early this morning he tweeted that “trade wars are good, and easy to win.” He is wrong, and beyond the simple fact of his wrongness, a trade war is probably more dangerous for investors at this time than at any other time in recent history given the implications it would have for inflation, monetary policy, and economic growth. The only positive from the tariffs is that it is a windfall profit increase for U.S. producers of steel and aluminum, which is at least positive for them. It is unlikely to cause any material increase in U.S. capacity to produce steel and aluminum and therefore unlikely to lead to many additional jobs even in those sectors. The negatives are much more significant. I believe these tariffs on their own will push inflation higher, and higher inflation is a threat to the valuations of more or less all financial assets today. But the greater threat is that this escalates into an actual trade war. A trade war would increase prices on a much broader array of goods and services, while simultaneously depressing aggregate global demand. This pushes us in the direction of not just inflation but stagflation, where both valuations and corporate cash flow would be under pressure. While there are scenarios that would be worse for financial markets — the proverbial asteroid on a collision path with Earth comes to mind — a trade war has the potential to be very bad for both the global economy and investor portfolios. As I wrote about last December, a significant inflation problem might well be the worst thing that could happen to a balanced portfolio, leading to losses on the order of 40%. A global trade war would be exactly the kind of economic event that could foreseeably lead to losses of that magnitude.

Trade wars are bad

As a general rule, when you add “war” to your description of an event, it’s a pretty strong suggestion that it is unlikely to be either good or easy. Wars are sometimes well intentioned (the war on drugs), occasionally necessary (World War II), but seldom good and more or less never easy to win. Even if you do “win” easily, the longer term implications are often more problematic than you thought (the second Iraq War). There is still some time for this particular war to be averted. But while it is our general contention that equity markets tend to overreact to political and economic events, this is not one of those times.

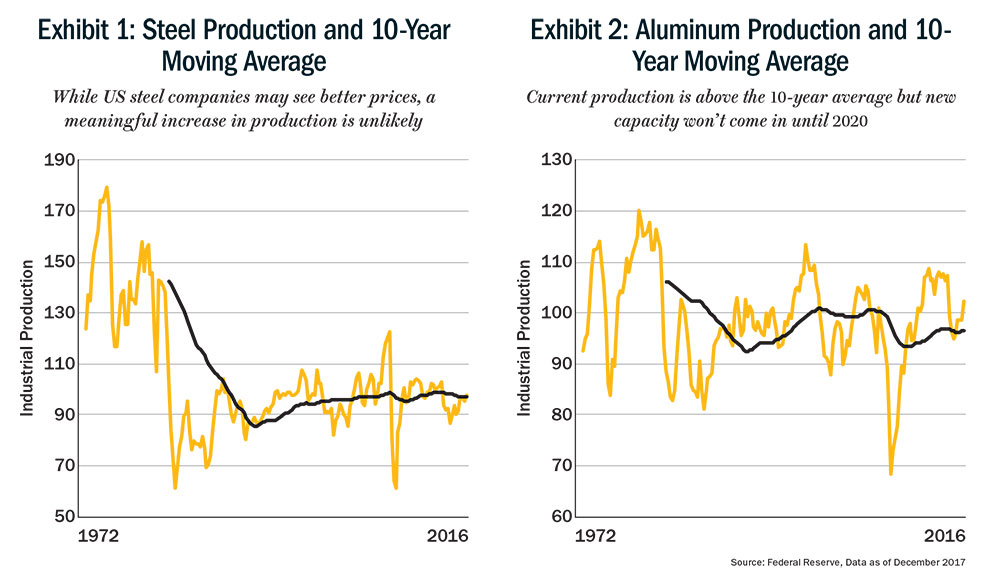

One obvious point about tariffs is that the entire purpose is to raise prices. Should these tariffs be imposed, higher steel and aluminum prices in the U.S. would not be an unwelcome side effect of the policy, but basically the entire point. If prices for steel and aluminum do not rise, there will be no U.S. jobs created or saved by U.S. based steel and aluminum companies. Furthermore, while U.S. companies would certainly benefit from a pricing advantage relative to their foreign competitors, I believe this is very unlikely to lead to a meaningful increase in domestic production any time soon. Looking at the production of steel and aluminum in the U.S. over time, there is no evidence that there exists a meaningful amount of spare capacity that could be easily and quickly turned on. Exhibit 1 shows the industrial production of steel in the U.S. against its 10 year moving average, and Exhibit 2 shows the same for aluminum.

If current production were well below recent averages, you could imagine that protectionist measures might readily lead to a ramp up in domestic production. With current levels at or above the average for the last decade, any material additional capacity that exists today may be antiquated and inefficient, and unlikely to be brought online. New capacity, and any resultant new jobs that came out of that capacity, would take significant time to come to pass, and it is hard to see that companies would be confident that the announced tariffs will be long lasting enough to justify new investment beyond what they already had planned. The president may be in favor of tariffs, but neither political party is a fan of them, and even if one could be convinced that Trump will not change his mind on the topic during his presidency, I believe new investment today would not likely come on line after until the 2020 election.

Trade wars are not easy to win

So from an economic impact standpoint, I believe there are unlikely to be a material number of new jobs created in the U.S. from these tariffs. On the other hand, it is not hard to imagine that jobs could easily be lost. There are hugely more U.S. workers involved in making the products that use steel and aluminum than there are U.S. workers directly in those sectors, and these tariffs and the resulting higher domestic prices for steel and aluminum relative to prices in the rest of the world suddenly make the U.S. a less attractive place to manufacture anything which uses those inputs.

The U.S. economy is large and diversified, and manufacturing is not a large percentage of total jobs, so these tariffs in particular are unlikely to have an outsized effect on overall economic growth. But at the margin, the tariffs would have to be expected to increase U.S. inflation, decrease growth, and decrease our export competiveness. And this ignores the impact of (what is extremely likely to be) retaliatory measures by U.S. trade partners.

Should these tariffs be imposed, the best we can realistically hope for is that things are contained at the level of a “trade skirmish,” where other countries respond with targeted tariffs or restrictions on a limited number of U.S. export products. Even this would make it even more likely that the net result of the tariffs will be net job losses along with the inflation increase.

But the real danger is that we see an escalation into a full-blown trade war. Given the rise of economic nationalism and increasing numbers of populist leaders with a shaky grasp of economics around the world, the likelihood of entering a trade war that is in no one’s best interest seems higher than should make one comfortable. Such a trade war would be a profound retreat from the globalization trend we have seen over the last 30 years. It can take years for companies to build out their global supply chains. With the stroke of a pen, political leaders can make those supply chains instantly far more expensive. But this does not make the process of building the domestic capability to replace foreign suppliers happen overnight. Such onshoring would necessarily take time, and frankly would not likely be possible in a lot of cases. In the meantime, widespread tariffs would mean large price rises. Those price increases, in all likelihood, would force the hand of the Federal Reserve to raise rates more aggressively than is currently planned, without any corresponding positive such as would come from an unexpectedly strong economy.

The psychological aspects of a trade war are not to be discounted either. One of the most striking features of investors today is their apparent willingness to look far into the future in assessing the value of investments. Whether this is in the form of high valuations for currently unprofitable but fast growing companies, or real estate and infrastructure investments priced with extremely long payback periods, investors today seem serenely convinced that they can predict what the future will look like. A global trade war could (and probably should) cause investors to shorten their time horizons, which is a negative for long duration risky assets such as equities. If one wanted to imagine a scenario in which valuations fall not merely to long term historical averages but right through onto the other side, a global trade war is a strong candidate.

What does this mean for our portfolios?

Despite everything I have written above, we have not made, nor are we planning, any material changes to our asset allocation portfolios. The proposed tariffs and the likely limited responses by our trade partners would probably constitute a net negative for U.S. stocks relative to the rest of the world, but we already are positioned for that given valuations. The tariffs do increase expected inflation at the margin, but we have already tried to position ourselves recognizing inflation as a threat. In benchmark-aware strategies, we are generally at (or are close to) our maximum bet against the U.S. equity market. In our benchmark-free strategies, we recently restructured our last material net U.S. equity exposure — our Quality strategy — as a long/short position against the S&P 500. In our multi-asset strategies generally, we have lower than normal weights in risky assets, less than normal duration, and own significant amounts of TIPS, which provide at least some inflation protection. While we by no means welcome these tariffs, we are comfortable with our current positioning given them.

Contrary to what Donald Trump appears to think, I believe that the U.S. imposing unilateral tariffs is more negative for U.S. companies than it is for the rest of the world. A full-blown global trade war would be a different matter, and we would expect emerging companies as the suppliers to the developed world to be particularly vulnerable. We have known this to be a risk for our emerging positions, and we do not currently see any reason to change it. We hope, and at this point expect, that cooler heads will prevail and a global trade war will be averted. But let’s be clear — no one would win a trade war, and investors should realize that they would lose along with everyone else.

The writer is the head of GMO Asset Allocation and a board member of GMO. Reproduced from GMO’s March 2018 Asset Allocation Insight

Just one email a week

Just one email a week