Romance. Seduction. These are the two powerful tools that fashion’s masters wield to great effect. When a brand or a designer is particularly good at getting attention, customers follow. And when the business is well run, profits soar.

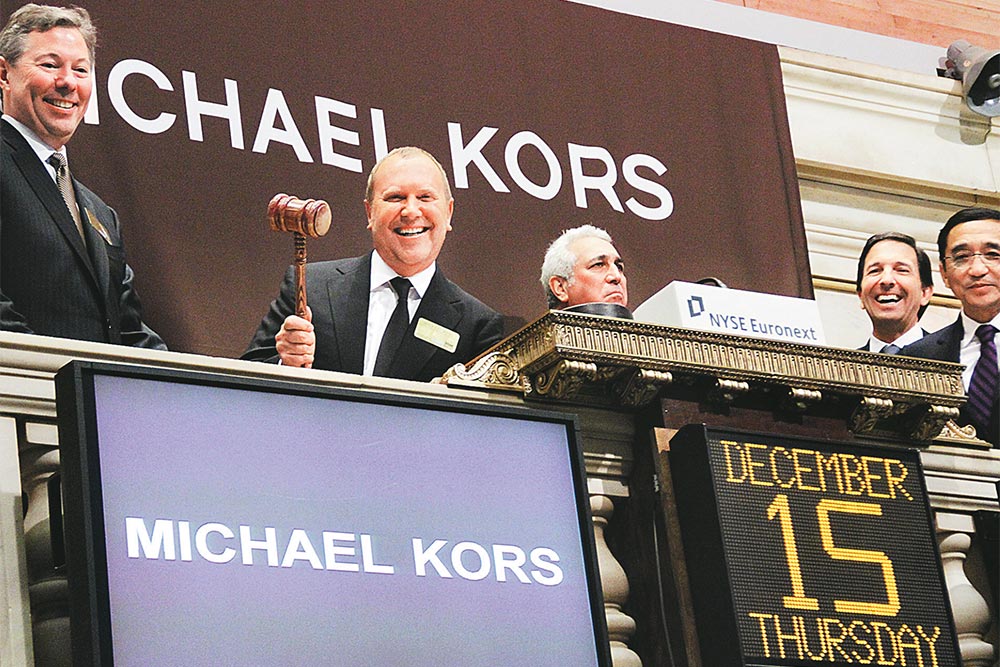

Then a different kind of dance begins. Investment bankers come knocking with hundred-million-dollar ideas, suggestions on how to take the company “to the next level.” Through their efforts, designer businesses have come to the market at a rate not seen in years. Prada, Salvatore Ferragamo and Michael Kors all took the plunge in 2011. Bruno Cucinelli followed in 2012. More could be in the offing.

Tory Burch is of perpetual interest to the investment set. And Diane von Furstenberg’s (DVF) business is being “professionialised” with the help of former Tommy Hilfiger executive Joel Horowitz, who has joined the company as co-chairman. Given Horowitz’s track record, an initial public offering could be in the cards, or at least an option as the business develops. In Italy, there are a host of companies laying the groundwork or believed to be considering offerings, including high-end jewellery firm Pomellato, menswear brand Stefano Ricci, Pianoforte, Ermanno Scervino and Dirk Bikkembergs. Each of these businesses has its own story to tell to investors.

Making new friends

Michael Kors was sold as the next Coach. Tory Burch would most likely be sold as the next Michael Kors. DVF could play on the designer’s broad recognition, but would need to back that up with some serious sales projections. Pomellato is being set up as another Brunello Cucinelli, but with a twist since it focuses on jewellery rather than apparel.

This is the age of the monobrand concept, but it isn’t only brands that are looking at an IPO — retailers are, too. However, retailers that carry a variety of brands have a more diffuse story to tell, which might ultimately be a harder sell for investors.

Hudson’s Bay [a Canada-based clothing superbrand] went public at the Toronto exchange in November 2012, raising around C$365 million, or $367.4 million — 8.8% less than the C$400 million initially projected. Private equity-owned Neiman Marcus is expected to return to public hands at any time, although experts note the chain will have to rely on the strength of its cash flow to attract investors, given concerns about the strength of the luxury market. The IPO payoff can be huge, but to get there, companies have to be ready to make some new friends.

Firms orchestrate a travelling “roadshow” to convince large investors to buy their stock at a set price. Those investors then turn around and sell their shares on the open market. As with all things finance, it’s a process driven by numbers, at least on the surface. Growth is what investors want — a highly profitable women’s brand with 100 stores and plans to add 200 more, while expanding into e-commerce — and perhaps men’s — is seen as a gold mine. A small chunk of that company bought early on will be worth all the more when the business expands.

But how does one convince jaded Wall Street types that the business plan is more than a PowerPoint presentation? That a brand is guided by a steady hand and clear vision? That growth is not just a possibility, but almost an inevitability?

That’s the art of the IPO and that’s when designers are usually called upon to switch on the charm, to ultimately convert investors into believers.

The big guns

Kors — with nine years as a judge on Project Runway and 71% brand recognition in the US — needed to do very little to get onto Wall Street’s radar. The roadshow was left to chief executive officer John Idol. Behind the scenes were Lawrence Stroll and Silas Chou, who, along with Horowitz, engineered the enormous wealth creation at Hilfiger in the 1990s.

On one Kors roadshow stop last year, Idol wooed 200 investors in The Pierre hotel’s Cotillion Room, and repeated the designer’s joke that “We’re the Hermes of Staten Island,” while laying out the growth plan.

The visible portion of the Kors IPO process was a lightning-fast two weeks in December 2011. Others carefully court investors over much longer time spans.

Entrepreneur Brunello Cucinelli triggered a small revolution by demanding that the roadshow process begin a year before his IPO. Instead of going to market, Cucinelli brought the market to him. Analysts and investors from China, India and South America travelled to the company’s headquarters in Solomeo — the Italian village the designer bought and restored. Investors participated in town celebrations, ate grilled meat and drank local wines at the main osteria, an informal restaurant. They also visited Cucinelli’s house with its neo-classical statues, busts of philosophers and a library with books in Mongolian, Chinese, Japanese and other languages.

One Chinese investor wanted 200 bottles of the olive oil Cucinelli produces in small quantities, while another group from China wanted to buy the village. Neither request could be accommodated, but Cucinelli made his point. The April IPO was 17 times oversubscribed.

“Investors appreciated the time they had (with Cucinelli),” said Federico Steiner, partner and general manager at Barabino & Partners, which advised the designer during the IPO and still consults for the firm. “This can be a key to success rather than the ordinary 30 minutes during the roadshow. It’s important to get to know an entrepreneur and his actions.”

Andrea Morante, CEO of Pomellato, recently said he was evaluating an IPO and was planning to speak with Cucinelli.

Morante’s own pitch is different from Cucinelli’s, but he sees similarities between the two businesses — both play in the niche luxury space, are expanding globally and don’t have many brand extensions. The CEO said Pomellato was among the first to offer “ready-to-wear jewellery” and the brand is seen as “unconventional and on the side of women,” with advertising that treats “women as subjects and not as objects.” Hollywood actress Tilda Swinton has fronted the brand for several campaigns.

“A brand must tell a coherent story so investors will know that it has a unique positioning, a point of view, a solid track record and an interesting future,” said Tomaso Galli, luxury goods consultant and founder of JTG Consulting. “During a roadshow, it’s more difficult to tell a complex story.”

The designer companies pitching investors now are relying on the clarity of a single powerhouse brand instead of the safety of a portfolio, à la LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton or PPR.

“People and investors need to be excited by both the story and the individuals behind the story,” says Laurent Feniou, managing director, Rothschild, London. “Investors will want to meet and to have a one-on-one relationship with the founder and the CEO. The person behind the brand is critical for the success of the IPO. The passion that is behind the brand’s past success and (that will be behind its performance in the) future has to be communicated.”

Investors want to know that the driving force behind a label isn’t going to take the money raised in the IPO and fade away.

“It’s important to get a sense — nearly a physical sense — of the passion behind the founder and the CEO,” Feniou says. “One consequence of that is that the CEO, the person behind the brand, needs to demonstrate that he or she is interested in institutional investors.”

With a little bit of TLC for Wall Street — and the right numbers — it shouldn’t be too hard for a designer business to attract the attention of investors.

“Retailers and brands are sexy. People can identify with them,” says David Shiffman, who is the MD at Peter J Solomon “When these big designers go to take their business public, the marquee name of the designer creates incredible buzz. You try to marry up the market cap expectations with the mind share recognition.”

When everything comes together right, there’s big money to be made. Just ask Kors, whose personal fortune has ballooned to over the magical $1 billion mark since the IPO in December 2011. Now that Wall Street’s reawoken to that fact, it’s clear that the IPO is back in fashion.

—New York Times News Service