There are times when even nerves of steel ain’t enough. That’s what’s happened with the steel industry, with global production shrinking 3% to 1,623 million tonne in 2015. Demand has been lower in most regions including the US and Europe. The biggest culprit though is China, which saw demand shrinking to 620 million tonne in 2015 compared to 710 million tonne in 2014. Considering that China alone consumes close to 50% of the 1,600 million tonne steel produced globally, it hasn’t been good days for the industry. For Indian major Tata Steel, its dead-weight European operations have only compounded issues and impacted profitability. Now, after years of trying to turnaround operations, Tata Steel has advised its European arm to “explore all options for portfolio restructuring including the potential divestment of Tata Steel UK, in whole or in parts.” The move, which comes amid operating losses, falling realisations and workforce issues, also follows the recent exit of its European head, Karl-Ulrich Kohler. Admitting that “in the recent months and quarters there has been a significant cash drain”, the company statement stressed that a time-bound sale was essential. The board also rejected another round of expensive restructuring for its strip products vertical. “It is clear that the company wants to get away from the UK market, which is positive because it will be able to conserve cash. While we need to see if Tata Steel can find buyers, if it is able to exit completely, they will be left with about 7 million tonne capacity in Netherlands, which is a profitable business,” says Rakesh Arora, head of research at Macquarie Capital.

The long string of bad news for Tata Steel started in January 2016 when Standard & Poor’s lowered its long-term corporate credit rating to BB- from BB. Soon, thereafter, Moody’s downgraded the company to Ba3 from Ba1 in mid-February. Moody’s went so far as to downgrade the UK operations to its lowest rating B3, saying the “consolidated reported leverage — as indicated by debt to EBITDA — stood at approximately 9x at end-December 2015, which is well beyond the tolerance level for Ba category rating.” Kaustubh Chaubal, vice president and senior analyst, Moody’s further said, “With no respite expected from the downward pressure on international steel prices, we anticipate the company’s leverage and coverage metrics to remain weakly positioned for the next 12 to 18 months.”

Debt mountain

Not just Tata Steel, most Indian steel companies have suffered over the last year or so because of the downturn in the industry, both in terms of price (due to influx of cheap Chinese imports) and demand. The twin reasons are also why these companies are having trouble servicing debt. Tata Steel owes close to Rs.75,000 crore to the banks, which is 25% of the banks’ total exposure to the steel industry. The debt, which was taken to largely support its loss-making European operations and the greenfield expansion in Kalinganagar, Odisha, is straining its financials. The scenario is so grim that most of the company’s cash flow is being used to service debt. In Q3FY16, interest cost of Rs.1,200 crore ate into the EBIT of Rs.1,300 crore, resulting in a net loss. Its annual interest outgo is about Rs.4,000 crore. Assuming a 10-year repayment period to retire the Rs.75,000 crore debt, Tata Steel would need an annual cash flow of over Rs.11,000 crore (inclusive of interest), which is much higher than estimated FY16 EBIDTA of around Rs.7,000 crore.

With little room to maneuver, Tata Steel is trying to raise money by selling non-core assets. Over the last 12-18 months, it has sold its stake in Titan Industries, a 50% stake in Dharma Port and a 25-acre land parcel in Borivli, Mumbai. It has also divested its stake in Tata Motors worth Rs.2,500 crore to institutional investors and Tata Sons. While the amount raised through these moves may not be more than 7-8% of its FY15 net debt, it has given the company some breathing space.

The company is also refinancing debt obligations so as to not put pressure on current cash flows. Banking on future cash flows, it recently refinanced $1.5-billion worth of loans. Out of the total capital employed by Tata Steel (Rs.146,000 crore excluding goodwill), 50% is not earning any money as of now. This includes over Rs.28,000 crore of capital-work-in-progress (for the ongoing Kalinganagar project) and over Rs.40,000 crore employed for the European business, which is currently making losses. If this non-remunerative capital starts to make a return, that will make a huge difference for the company. For instance, at 10%, the company will make an additional operating profit of Rs.7,000-8,000 crore.

That would be ideal but how close is that to coming through? The first phase of the Kalinganagar project, with a capacity of 3 million tonne, will be operational by end-FY16, taking Tata Steel’s domestic manufacturing capacity to 13 million tonne. The production will ramp up in a phased manner, with 1-1.5 million tonne coming in FY17 and close to 2.5 million tonne in FY18. But the new integrated facility, at the current realisation of Rs.36,261 per tonne and EBITDA of Rs.6,100 per tonne, will bring in additional cash of around Rs.2,000 crore. If one considers the FY17 EBITDA estimate of Rs.8,950 per tonne, cash flow would increase by about Rs.2,500-3,000 crore.

The worst half

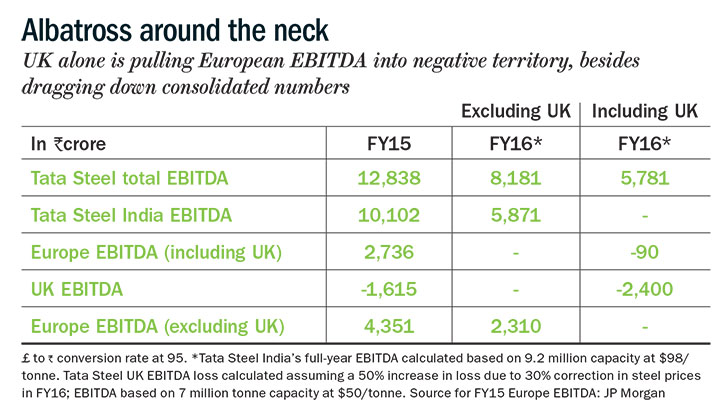

But it is in the far shores that its Achilles heel resides. “In 2007-08, Europe was consuming close to 210 million tonne of steel as compared to 150-155 million tonne currently. Because of demand erosion and cheap imports, pricing power has eroded and companies in Europe are making losses. Amongst Tata Steel group companies, the UK facility has been hit the hardest, which is the cause for losses in Europe,” says Pritesh Jani, analyst, Religare Capital.

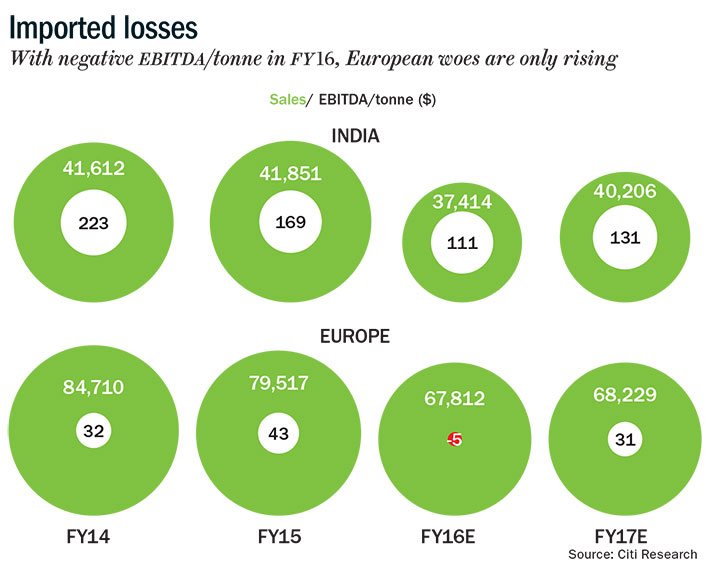

In Q3FY16, Tata Steel posted a 72% decline in its consolidated EBITDA, largely due to losses in Europe. Tata Steel Europe logged negative EBITDA of $31 per tonne as against EBITDA of $98 per tonne back home. While the European operations produce close to 14 million tonne of steel, production costs are higher at $380-400 per tonne compared to around $280 in India. Besides, higher employee costs and poor performance of some indirect subsidies also weighed on the company in the quarter.

The European division is now striving to bring down costs by focusing on high-value products and reducing production in loss-making facilities as well as fuel costs. In Q3FY16, European business produced 3.56 million tonne of steel compared to 3.74 million in the corresponding quarter last fiscal. This resulted in a saving of close to Rs.500 crore in the December quarter. “Manufacturing improved because of the initial positive results of restructuring including the mothballing of the strip mill in Llanwern,” Kohler had said in a recent analyst call.

But the catch is that the European operations not only have to return to positive EBITDA but also earn an interest cost of about $35 per tonne. The company’s deal with Greybull Capital for its long products division, however, will offer some respite. Greybull is arranging a $570 million package for the division, which caters to railways and construction industry, employs 4,700 people and has an annual capacity of 4.2 million tonne. Investors had long been awaiting the deal, saying it will reduce cash requirements. The division had fallen prey to lower demand and falling steel prices in the region. “Steel demand in Europe grew at 2-3% in 2015, but more than 80% of that growth has been taken up by imports. Low price imports are harming prices and bringing margins down,” said Kohler. In FY15, the European business needed cash of about Rs.6,000 crore, largely for funding losses, interest and maintenance capex.

Low visibility

Back home, the Kalinganagar project would help ramp up volume and bring in cash. Raw material costs, too, are expected to fall as its captive mine in Noamundi, Jharkhand has resumed operations after almost one-and-a-half-years. The company procures close to 5 million tonne of iron ore or 30% of its total requirement from this mine, and had to buy iron ore from the market while it was shut. “For the first time in its history, Tata Steel had to purchase iron ore from domestic and international sources. As a result, we faced significant pressure on our supply chain, which adversely affected costs,” said Group executive director Koushik Chatterjee in Tata Steel’s FY15 annual report. In FY15, raw material costs for the company jumped 20% to Rs.14,170 a tonne as iron ore costs alone went up by 85% to Rs.4,190 a tonne. The outgo on iron ore is expected to normalise from end-FY16, barring any carry-over inventory of external purchases from FY15.

The hike in steel prices post imposition of minimum import price (MIP) by the government has also come as a breather. MIP was introduced in February this year to check Chinese imports that had lowered domestic capacity utilisation to 75%, the lowest in a decade. Tata Steel has since raised prices by Rs.1,500 per tonne. While MIP should ensure higher realisation, additional supply due to commissioning of new capacities by Tata Steel, SAIL and NMDC over the next 12-18 months should cap the upside. Another factor is how the prices would swing once MIP expires in August this year. China steel export prices are at $310 per tonne currently, adding another $20 as import price, the final price would be $335 per tonne, still below the MIP set at $445 per tonne. How this equation plays out remains to be seen, but analysts don’t expect domestic prices to cross $445 per tonne in a hurry. Government’s increased spending on infrastructure and expected pick up in rural demand though bode well for the company.

The initiatives undertaken by Tata Steel at best address near-term pressure. The larger picture will be clear after 18-24 months when the Kalinganagar project goes onstream and restructuring in Europe fructifies. The demand-price scenario is another factor. Even if demand in India, which has come down from 10-11% in 2015 to 5-6% currently, improves, prices are unlikely to takeoff considering global woes. To put things in perspective, the company is expected to pull in an EBITDA of Rs.13,000 crore in FY17 and Rs.15,000 crore in FY18, respectively. “Steel prices have moved up by $15-20 a tonne internationally, and this should aid a margin recovery. To meet our FY16 estimates, it needs a positive EBITDA per tonne of $27, which looks highly unlikely,” says Arora. While its FY17 estimates of $22 a tonne margin might be possible now that the long products division is out of the way, investors are waiting for the sale of the Wales plant. In the interim, most analysts tracking the stock have a ‘sell’ or ‘hold’ rating, with average 12-month price target of Rs.220 as compared to the current market price of Rs.320. So, the odds are still not in Tata Steel’s favour if one goes by analyst consensus.