For over a decade, India’s start-up ecosystem followed a familiar formula. First pilot your service in a metro. When the platform sees the first rushes of growth, raise funds to expand to other cities. Once there is substantial scale in the top-10 cities, look towards the hinterland.

Rapido’s founders saw a flaw in that playbook. It was just too costly. Moreover, they realised that in a country of 1.4bn people, existing players were catering only to the top 10–20mn users, leaving the next 100–500mn without a choice. When another co-founder Pavan Guntupalli was without a job, he felt the problem of mobility first-hand. There was no convenient and affordable commuting option.

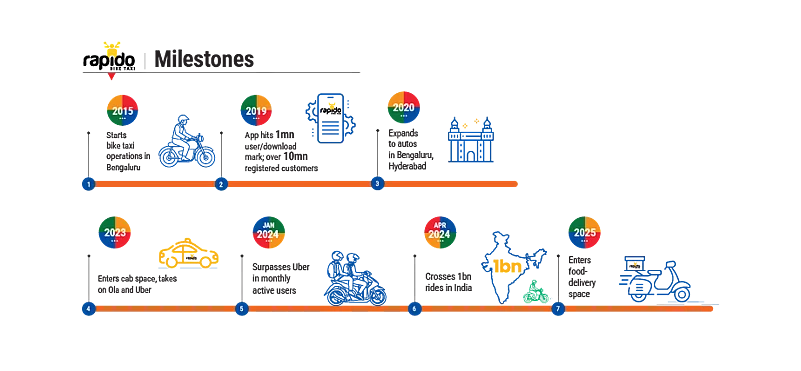

Without any blue-chip backers and little capital in hand, Rapido had to do things differently. In 2015, it started with bike taxis, not cars, and focused on smaller cities.

“We launched in Mysuru and Vijayawada before even considering Delhi or Chennai. We focused on finding ways for them [drivers] to earn more through consistent demand,” says Aravind Sanka, co-founder, Rapido.

When Risk Paid Off

Meanwhile, Mysuru, with its narrow roads and modest commuters, became a laboratory. From there, Rapido validated its model and scaled it across small and mid-sized cities which investors had dismissed as too fragmented to matter. Ola and Uber were already dominating metros, and few saw sense in competing for smaller towns.

Even when it had a breakthrough moment in Delhi in 2016 as the state government introduced the odd-even scheme to curb pollution levels, it capitalised on the opportunity to gain a foothold first in nearby cities like Bareilly, Meerut, Saharanpur, Moradabad and Aligarh. Today, 40% of Rapido’s revenues come from Tier-II and Tier-III cities.

A decade later, the once-dismissed experiment from Mysuru has disrupted the Indian ride-hailing market.

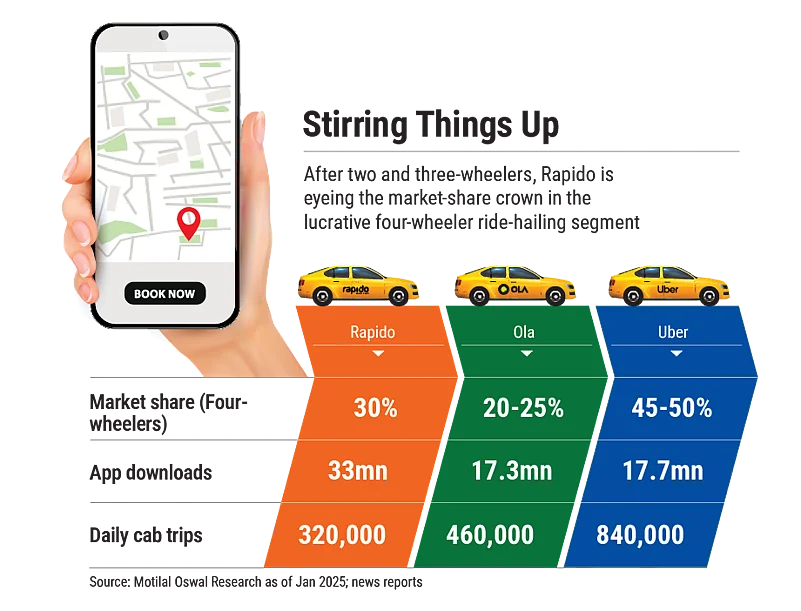

Earlier this year Rapido became the leader in India’s ride-hailing market across vehicle types with nearly 50% of the market, while also becoming the No. 2 player in the cab segment.

By July, Rapido reported managing 4.3mn rides a day across its bike, auto and car fleets. A figure the company says is around 40% higher than Uber’s and nearly triple Ola’s.

“The reason we left our jobs and started up 10 years back was we wanted to create impact at scale. And that’s why we didn’t give up easily even though things were difficult,” says Sanka.

Today investors are lining up to fund the company. After entering the unicorn club last year, it is now reportedly in talks to raise a mammoth $500mn round led by Prosus, a big tech investor.

Maths Behind the Miracle

It’s often presumed that founders with an IIT background find it easier to raise funding for their start-ups. But when Rapido, with two of its three founders boasting the IITian tag, hit the funding circuit a decade back, it was in for a rude shock. The techies endured as many as 75 rejections from venture capitalists.

One of the biggest red flags for investors was the impossible challenge Rapido was up against. Uber and Ola were burning millions of dollars every month to capture India’s ride-hailing market. And backing the two was a seemingly infinite pool of cash from daddy investors like Google, SoftBank and the Saudi sovereign fund.

But serial entrepreneur and investor Kunal Khattar, who had returned to India after a decade in Silicon Valley and Wall Street, had a contrarian take.

“Roughly 90% of vehicles on Indian roads are not four-wheelers. Even at a ₹250 ride, our calculations suggested only 1–2% of Indians could afford that. At a ₹50 fare, perhaps 5–10% of Indians could afford a bike trip,” says Khattar, who wrote a cheque for Rapido in those early days.

The arithmetic was simple but ambitious. Almost 75% of India’s 230mn registered vehicles at the time were two-wheelers and mostly owned by either middle- or low-income groups. Rapido could turn these two-wheelers into the fastest and cheapest ride-hailing fleet on the busy and narrow roads of urban India, while offering anyone with a bike a gig to pocket an extra buck.

Of course, Uber and Ola were quick to jump onto the two-wheeler bandwagon. But they dipped their fingers in too many pies from cabs to bikes, ride-hailing to food delivery.

Rapido’s bet on two-wheelers also helped lift the company’s profitability, compared to rivals who went all in on cabs.

Unlike Ola or Uber, Rapido didn’t need to manage fleets or finance drivers. Each ‘captain’ uses their own bike, while Rapido provides the technology platform and matching engine.

By the time Rapido expanded into cabs in 2023, it had already achieved over 25mn app downloads and built a customer base exceeding 10mn, becoming the leader by a distance in the bike segment.

Meanwhile, the strategy to bank on Tier-II, -III cities has paid off in terms of its unit economics. The company’s per user acquisition cost is less than ₹60 for customers and around ₹150 for drivers, which are among the lowest in the ride-hailing industry.

“Tier-II and -III cities are low-density markets, it’s hard to make them functional. But once you crack it, you can lead because few others are willing to invest or build capabilities there,” says Arpit Agarwal, partner at venture-capital firm Blume.

Paradigm Shift

When Uber and Ola burst onto the scene in the previous decade, they came with all guns blazing. While consumers got dirt cheap rides in AC cars, it was the cab drivers who struck gold. Word spread that one could make ₹40,000 a month by driving a cab.

The good times didn’t last long. Once most of the rivals were driven out of the market, Uber and Ola clawed back the subsidies for drivers and increased their share from fares. When Covid struck, lakhs of drivers hit their lowest point.

Meanwhile in Bengaluru Namma Yatri, a ride-hailing platform, saw an opening. It innovated a subscription model wherein drivers pay a daily or monthly subscription fee to get customers, rather than the typical 20–25% fee on a fare. But it could not scale up quickly due to lack of funds.

Rapido, which in 2022 had bagged about $200mn from online food-delivery company Swiggy and TVS, a motorcycle-maker, grabbed the opportunity with both hands and introduced this model at a subscription charge of around ₹20–25 per day to autorickshaws first and then used it to launch its four-wheeler segment in late 2023.

“We felt that the cost to the company shouldn’t depend on whether it’s a ₹100 ride or a ₹500 ride. So, why should a captain pay more? That thinking helped us design a fairer, more scalable system,” says Guntupalli.

And drivers lapped it up fast. By September this year, it had already cornered 30% of the car segment where the ticket prices are much higher. This has forced even its rivals Ola and Uber to follow suit. Meanwhile, the number of drivers on Rapido has gone from 700,000 before the new model to over 2mn now.

“What stands out is the team’s understanding of local markets and their obsession with execution.

Their growth has come from local innovations rather than copying global playbooks,” says Saurav Jain, principal investor, India Ecosystem, Prosus.

On its part, Rapido has been always eager to look at the right opportunity at the right time. For instance, in 2020, a pain point for the company was the lockdown.

That’s when they decided to deepen a pre-existing partnership with Swiggy and worked with the government to deliver essentials. It also partnered with retailers Big Bazaar, Spencer Retail and Big Basket.

Long Road Ahead

Many of its bike riders work across both logistics and ride-hailing.

About 25–30% handle both segments, while most focus on one. Now, the company is betting on this gig workforce to pave its way into food delivery. It recently launched an app called Ownly.

Industry insiders point out that this is a natural move for a ride-hailing platform. Every such company eventually thinks, “If we can move people, we can move food.” Both Ola and Uber have tried doing it in India but have not succeeded.

“Rapido, on the other hand, learned the ropes while partnering with Swiggy, they learned about delivery logistics, optimisation and handling food versus passengers,” says Satish Meena, founder, Datum Intelligence.

The timing is significant, coming at a point when restaurant owners have repeatedly voiced concerns over high commissions and non-transparent ad deductions by Zomato and Swiggy. Customers, too, have grown frustrated with the rising cost of food orders.

While Rapido cut its losses by 45% to ₹371 crore in 2023–24, compared to the previous year, how this diversification plays out will also be important for its future profitability as food delivery is a high-frequency, big-ticket use case that can drive larger revenues.

Experts say Rapido’s success or failure in food delivery will depend on its ability to raise funds to compete with the massive war chests of Zomato and Swiggy. Can it prove its detractors wrong once again?