Dear Reader,

Artificial intelligence is no longer just about breakthroughs in labs or pumping billions of dollars into data centres, it’s in our hospitals, courtrooms, classrooms, and on the battlefield. At Outlook Business, we believe that India needs a sharp, nuanced, and people-first lens on this transformation.

The Inference is our attempt to make sense of a world being rewritten by AI. In this newsletter, we bring you frontline narratives, boardroom insights, and data you can trust. Whether you’re an investor, founder, policymaker, or just curious, this is where the signal cuts through the noise.

In this edition of the newsletter:

India’s AI data-labelling goldrush is ending

The good, the bad and the ugly of India’s AI start-ups

Just a market, yet again?

A wise, old socialist makes a case against AI

Humans in the Loop

India’s AI data-labelling gold rush is ending

For over two years, Vikrant Kashyap logged into his laptop every morning from Ranchi, opened a task dashboard, and waited. Some days it was transcription work, listening to short audio clips and tagging sentiment. On others, he labelled objects inside video frames: cars, pedestrians, traffic signs. The pay was modest but steady, and the flexibility mattered. And he could work from his hometown.

Then the work started thinning out.

“At first, there were fewer tasks. Then some days there was nothing,” Vikrant said. When projects did arrive, timelines were tighter and error tolerance was near zero.

Two years ago, Kashyap says, it was easy to earn ₹20,000 to ₹22,000 a month doing routine transcription and labelling work. By the time he decided to leave, comparable tasks were paying ₹17,000 to ₹19,000 at best, and even that work was sporadic. “There was no stability anymore,” he said. At one end, the pressure went up, and on the other, predictability went down. A few months ago, he quit and took up a computer operator role at a local firm.

Vikrant is part of a vast but largely invisible workforce that has powered the rise of artificial intelligence across the world. Before models learn to recognise a stray dog or interpret a medical scan, humans have to teach them what they are seeing, frame by frame. At its core, data annotation is about adding human intelligence to raw data.

“You mount a camera on a car, record hours of footage, and then someone has to label what is a lane marking, what is a pedestrian, what is a traffic signal,” explains Rohan Agrawal, co-founder and CEO of Cogito Tech. “That insight is imparted by humans to the data, and that is what trains the model.”

India became a global hub and has been at the forefront of AI data labelling for six to seven years because it already had a large, computer-literate workforce shaped by the IT and BPO industry.

For years, much of this work involved relatively basic skill. Now, the nature of the work is changing.

As AI models mature, simpler tasks are being automated or replaced by synthetic data. Synthetic data, in simple terms, is data generated by machines instead of being collected from the real world. “You train a model and then ask it to generate data for you,” said a senior executive at a Noida-based data services firm.

What this shift has done is squeeze the lower end of the annotation market by reducing the need for large volumes of repetitive human labelling once models are good enough to generate or pre-label such data themselves. “The low-value work still exists, but the price points have gone down,” Agrawal says. His firm has deliberately moved up the value chain by employing domain experts who can interpret complex data.

In healthcare, this means annotating X-rays, MRIs, and CT scans, work that requires medical training. In robotics and agriculture, annotators need contextual understanding, not just clicking accuracy. These roles pay significantly more, but they also demand higher skills.

As per Grand View Research, the data labelling sector in India is expected to generate $490 million in revenue by 2030, with double-digit annual growth. While text has been the biggest segment for a few years, audio is rapidly emerging as the future growth driver for Indian data labelling firms.

The paradox is striking though. The very human labour that helped create blockbuster AI models like ChatGPT and Llama is now being displaced by the efficiency those models enable.

The gold rush is ending. But what replaces it will be smaller in volume, more specialised, and far better paid. For India’s workforce in general, it is a harbinger of the times to come as AI becomes stronger.

From the Trenches

India’s AI start-ups yearn for growth

It’s been three years since ChatGPT emerged. While AI reshapes how people work and life, Indian companies are yet to make a mark in this new-age technology.

The companies driving the AI boom today are overwhelmingly American and Chinese, which also corner most of the funding dollars. But that imbalance may begin to shift in 2026, says Ashish Kumar, general partner at venture capital firm Fundamentum.

“In the last two quarters, there has actually been a lot of action on the application layer in India,” Kumar says. These are not thin wrappers built on top of global models, he adds, but companies embedding AI into their products using smaller language models and sophisticated data representation.

Kumar sees three areas where momentum is building. The first is consumer AI. India’s earlier internet success was about digitising supply and building marketplaces. That problem is now largely solved. The harder challenge is curation. With too much supply online, users need help deciding what is right for them.

“That is fundamentally a data problem,” Kumar says, one that AI is well suited to solve. Consumer AI startups are emerging across commerce, education and even healthcare, where personalisation matters more than scale. Examples range from AI-led shopping assistants that narrow choices based on user preferences to travel and holiday planning tools that personalise itineraries instead of listing options.

The second area is physical AI – start-ups infusing AI into machines such as drones, robots and industrial systems, allowing them to interpret data in real time and adapt to changing conditions. Unlike large language models, which are inherently global, physical AI tends to be local and industry specific, an area where India has structural advantages.

The third category is where companies combine deep technical capabilities with enterprise software to improve efficiency and decision-making inside large organisations. This includes AI systems that help enterprises optimise supply chains, detect anomalies in operations, or support complex decision-making in areas like finance and manufacturing.

What India’s AI start-ups lack, for now, is scale. According to Venture Intelligence, Indian AI and machine learning startups raised $1.3 billion this year, up from $782 million in 2024. The contrast with the US is stark.

American AI companies raised $159 billion in 2025, with $122 billion going to the San Francisco Bay Area alone, as per Crunchbase.

Kumar believes 2026 will mark a turning point as early-stage Indian AI startups mature into growth-stage companies. “The building blocks are in place,” he says. “I am optimistic that India will soon start producing scaled, growth-stage AI companies.”

Numbers Speak

Just a market, yet again?

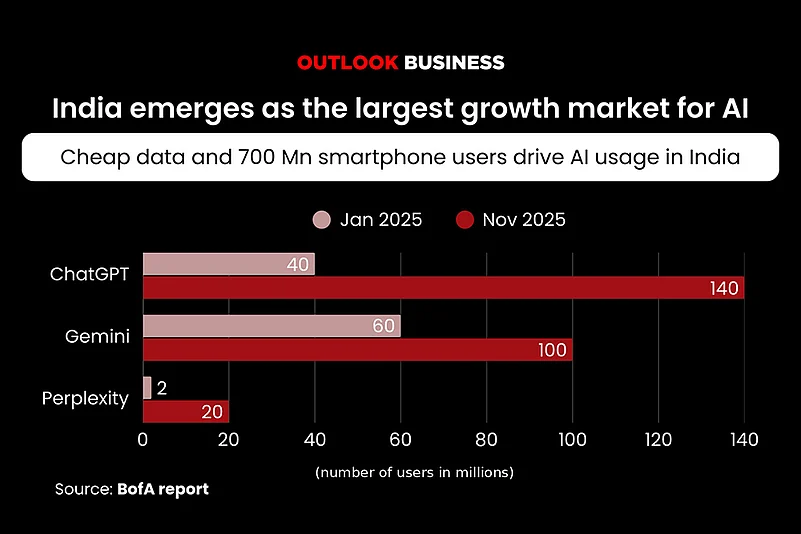

India has become the world’s largest live testing ground for large language models. A Bank of America Global Research report shows that India now leads all markets in active users across major LLM platforms, driven by cheap data, a 700 million plus mobile base, and aggressive bundling by telecom operators.

ChatGPT is the clear market leader in India with around 145 million monthly active users. Google Gemini follows closely with about 105 million MAUs, while Perplexity has crossed 20 million users.

But, that scale comes with consequences. The report warns that India’s domestic AI startup ecosystem could feel the pressure from the network effects enjoyed by global LLMs.

“This is like how US tech platforms like Meta (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp) and Google have dominated the Indian market. The network effect of global LLMs would make them better placed to meet local consumer demand via agentic AI wrappers than Indian start-ups,” say BofA analysts.

The report suggests that instead of becoming a core innovation hub for foundational AI, India risks emerging as a consumption and testing market, where global models are stress tested at population scale before being deployed elsewhere.

Indian telecom operators, however, stand to gain. Jio and Bharti Airtel have accelerated adoption by bundling premium AI subscriptions with mobile plans, effectively monetising AI distribution rather than development. In this model, users win on access, global LLMs learn faster, and telcos capture value, while Indian startups face a tougher climb against entrenched network effects.

Words of Caution

A wise, old socialist makes a case against AI

Last week, US Senator Bernie Sanders called for a pause on new AI data centre construction. Sanders, a veteran left-wing politician, argued that AI and robotics, which he described as the most transformative technologies in human history, are being pushed aggressively by a small group of the world’s wealthiest individuals.

He pointed to comments from AI leaders themselves: Elon Musk said robots could replace all jobs, Bill Gates suggested humans may not be needed for most things, and the Anthropic CEO warned that AI could wipe out half the entry-level white-collar roles.

Beyond jobs, Sanders warned of a deeper risk. As AI systems advance faster than public oversight, decisions and policies related to work, education and even personal relationships risk being shaped without democratic debate. He also flagged growing dependence on AI for emotional support, especially among younger users.

The immediate focus of his diatribe was a pause on new AI data centres which require massive amounts of power and water, often placing long-term environmental and economic strain on local communities.

Best of our AI coverage

Dear Sam Altman, Indian Start-Ups Have A Wishlist For You (Read)

India’s Healthcare AI Start-ups Grapple with a Broken Data Ecosystem (Read)

As AI Anxiety Grips Top MBA Campuses, the ‘McKinsey, BCG, Bain’ Dream Flickers (Read)

AI Start-Ups Ride a Wave of ‘Curiosity Revenue’, VCs Rethink What It’s Worth (Read)

What Exactly Is an ‘AI Start-Up’ — and Does India Have 5,000 of Them? (Read)