Skariah K George, 52, bought his Maruti Suzuki WagonR back in 2014. For years, the resident of Thiruvalla has sworn by it because of the car’s mileage, its stubborn reliability and the ease with which the service centre replaced parts without fuss.

Suffering from persistent back pain, WagonR’s upright seating and tall-boy frame had been a blessing for him. The car had never once stranded the family on the road. “It never let us down,” his son Blesson Skariah recalls.

But when the time came to replace it, father’s loyalty and son’s aspirations pulled in different directions. Skariah wanted another WagonR. His 21-year-old son insisted on a sports utility vehicle (SUV). “Obviously Kia,” Blesson says, “they have futuristic designs”.

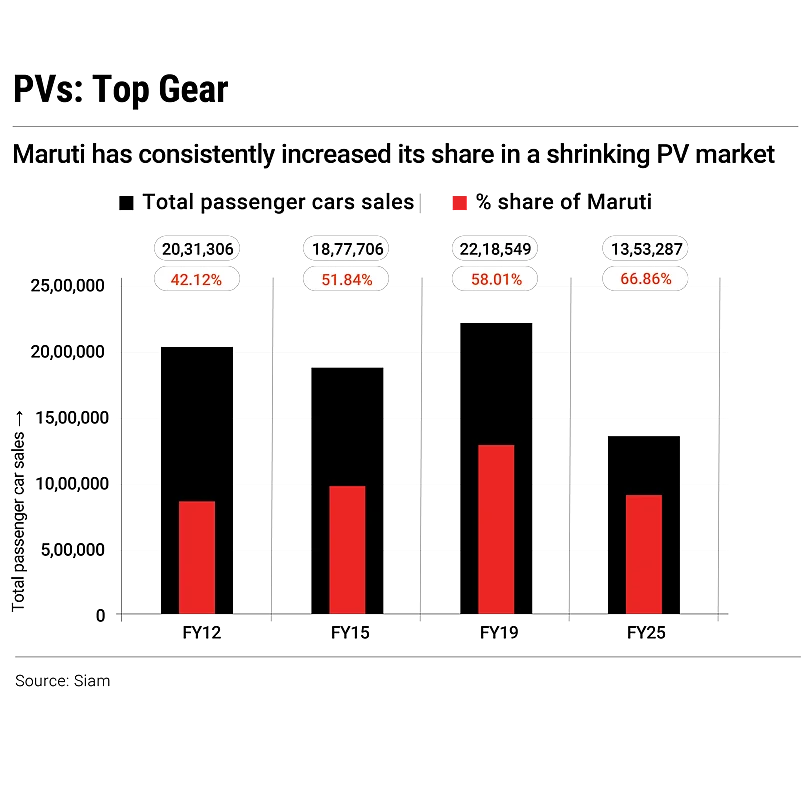

This tug-of-war between loyalty and aspiration is playing out across India’s passenger vehicle (PV) market. Maruti Suzuki India—Maruti—the undisputed leader for decades, is ceding ground to smaller rivals who once were blips in the rear-view mirror.

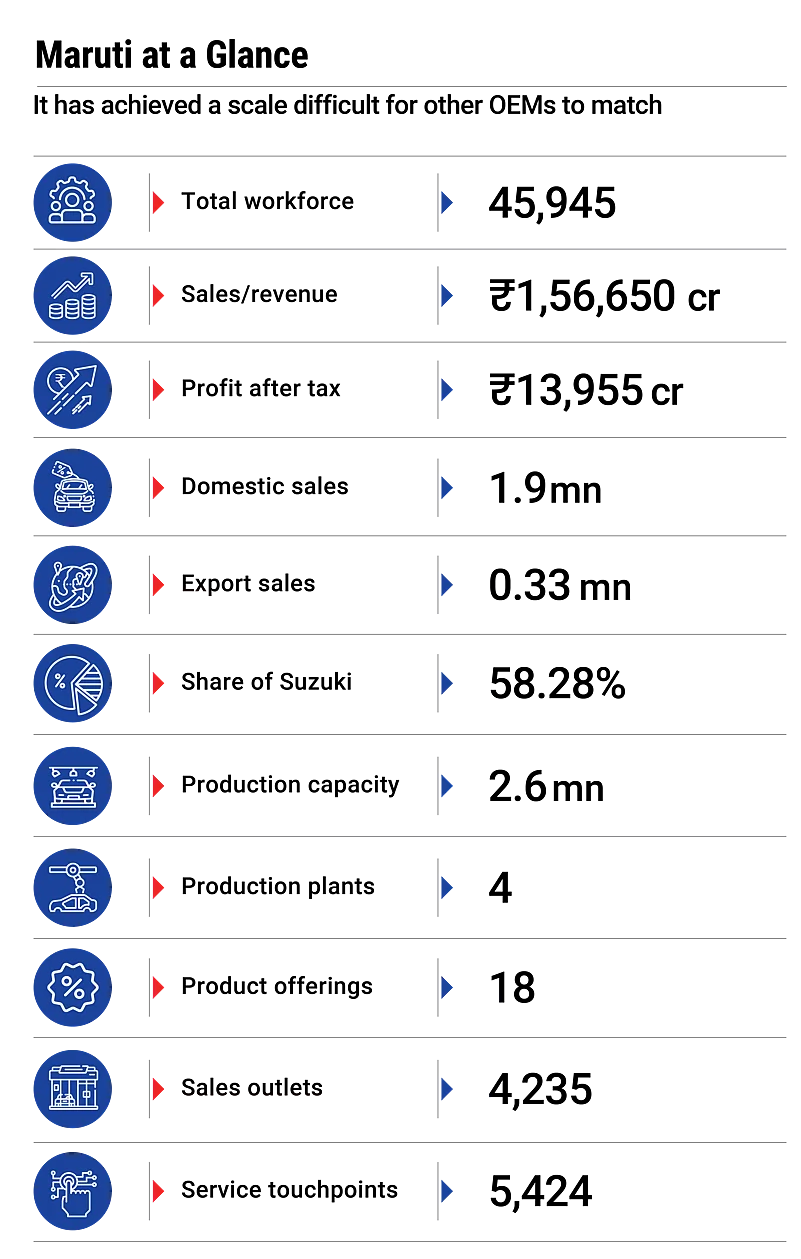

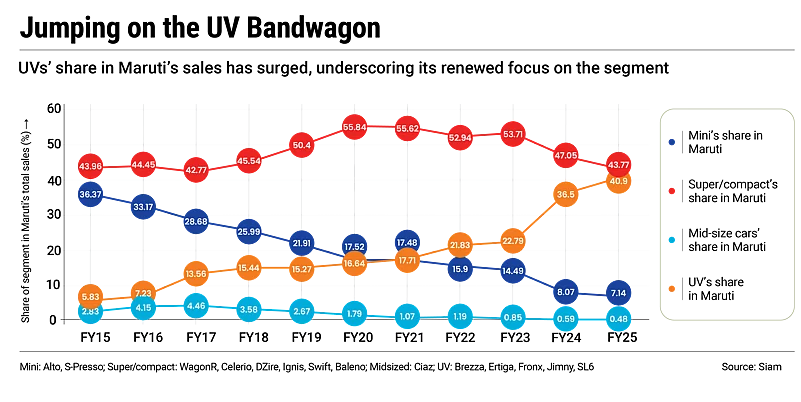

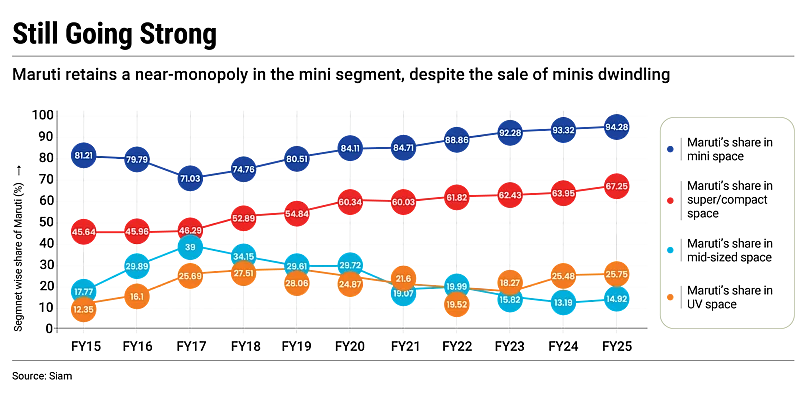

Between 2018–19 and 2024–25, Maruti’s market share fell by more than 10 percentage points—from 51.2% to 40.9%. The WagonR still rules Indian roads, giving Maruti an enviable edge.

Yet the hatchback segment that WagonR belongs to, has shrunk by over 23 percentage points in the PV market, from 46.9% in 2018–19 to 23.6% in 2024–25. Maruti now confronts the classic incumbent’s dilemma: cling to the formula that made it king for decades or turn to newer battlefields where rivals are gaining ground?

SUV Market Growth India

The first cracks appeared in the last decade as young, urban buyers began seeking something more aspirational. Car commercials reflected the shift. The dutiful son buying a Maruti 800 to please his parents gave way to a stylish couple in a Honda Brio, with Western music playing in the background. The cues were clear: buyers now wanted style and individuality.

Hyundai’s i20 brought a touch of European flair to hatchbacks. Honda’s Brio targeted young, first-time urban buyers, while Toyota’s Etios Liva promised cabin space and ground clearance suited for Indian roads.

“It was a time when India’s aspirations were changing. The market was moving from functionality to aspiration…disposable incomes were on a rise, international travel was showing young Indians new cars,” says Tarun Garg, chief operating officer, Hyundai Motor India.

Maruti now confronts the dilemma: cling to the formula that made it king or turn to newer battlefields where rivals are gaining ground?

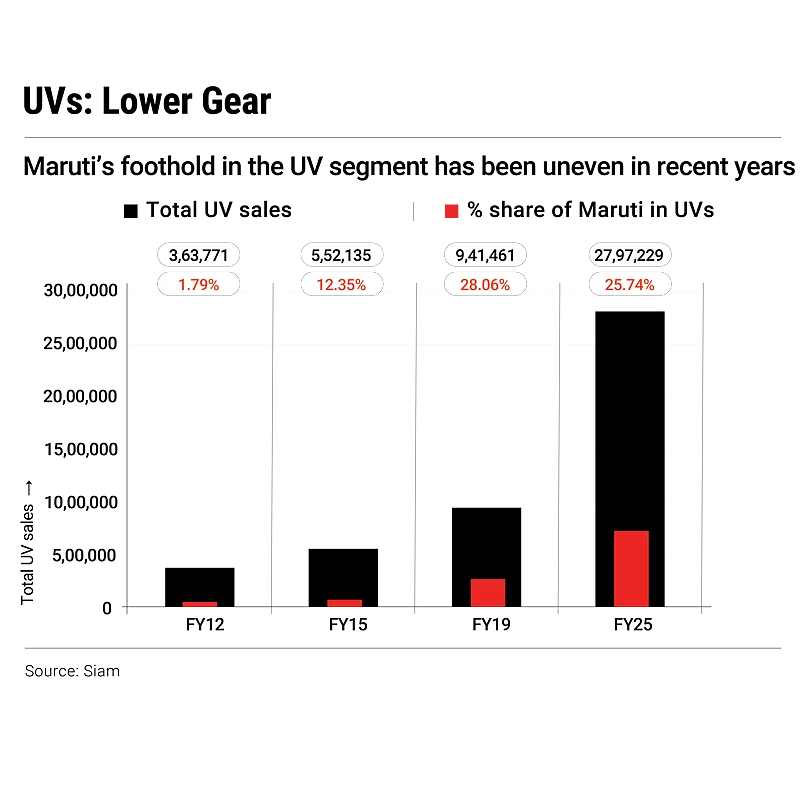

Maruti’s rivals recognised a once-in-a-generation opening. Between 2018–19 and 2023–24, automakers launched more than 30 new SUVs. In contrast, just four hatchbacks and three sedans entered the market. SUV sales nearly tripled, while hatchbacks shrank 25% and sedans plunged 40% during the same period. In 2024–25, SUVs accounted for over 55% of the PV market from 23.7% in 2018–19.

Hyundai was among the first movers. Its 2015 Creta was compact enough for cities, stylish enough for young buyers and packed with features at a price aspirational households could afford. It became a blockbuster.

Tushar Gupta, 40, had bought a Maruti Swift in 2010 for the brand’s traditional strengths of reliability and mileage. When the time came to upgrade, he chose a Hyundai Creta instead. “I wanted more than just a way to get from point A to B,” says Gupta, who works at a multinational company in Gurgaon.

Over the past decade, every major carmaker has launched models in the SUV segment. Tata Motors raised the stakes with the Nexon, whose design, safety ratings and competitive pricing appealed to young buyers. Kia entered with the Seltos, offering segment-first features such as ventilated seats, connected technology and a 360° camera, all wrapped in an aggressive design. Mahindra & Mahindra (M&M), long seen as a maker of rugged SUVs, reinvented itself with the XUV700 and Scorpio-N.

“These cars did not just provide mobility but a whole driving experience,” says Vinkesh Gulati, former Federation of Automobile Dealers Association (Fada) president. “With multiple engine options and feature-based variants, they had something for everyone.”

Maruti Comeback in SUV Market

On the outskirts of Jaipur, a convoy of Maruti’s newest SUV cut through wide highways and dusty trails, each wheel turned by a journalist invited to test the company’s latest bet, the Victoris. As the car manoeuvrered through the crowded lanes on the way to Amer Fort, it drew curious glances.

“Could you please open the tailgate. I want to see the boot space,” asked a local—a young woman in her late 20s, the very demographic Maruti is targeting with the Victoris.

With deliveries already begun last month, the mid-sized SUV is positioned between the Brezza and the Grand Vitara as the flagship of Maruti’s Arena chain, a network of mass-market car showrooms.

The Victoris is Maruti’s clearest sign yet that it has been studying its rivals closely. It comes with petrol, mild-hybrid, strong-hybrid and compressed natural gas (CNG) options, a level-2 advanced driver assistance system (ADAS) and a 5-star Global New Car Assessment Programme rating.

In a segment long dominated by the Hyundai Creta, Maruti is signalling that it is ready to compete on features, safety and technology, not just mileage and reliability.

“Today’s buyer is not looking for just power and torque but for a wholesome experience. And we will provide that [through Victoris],” says Partho Banerjee, the company’s senior executive officer, marketing & sales.

Gen Z Car Preferences India

The Victoris is not Maruti’s first SUV. It first entered the new age SUV market in 2016 with Vitara Brezza. After early success the company expanded its Nexa (premium) dealerships to reach buyers and introduced models such as the Grand Vitara, Fronx and Jimny. The Jimny, aimed at M&M’s cult model Thar, failed to find strong traction, but the broader portfolio has given Maruti a firmer footing. In 2024–25, the company secured the No. 2 position in SUV sales with more than 4,88,000 units sold.

According to automotive-data provider Jato Dynamics, it sold over 1,39,000 SUVs in the first four months of the current financial year. SUVs now account for nearly 28% of Maruti’s sales, up from just 8.9% in 2020–21. “This has helped Maruti balance the shift in demand,” says Ravi Bhatia, president and director, Jato Dynamics India.

But this is not enough. To corner 50% of the market like the good old days, Maruti needs a sharper connect with young buyers. “The strong growth of competitors such as M&M is challenging traditional market structures across the industry,” Bhatia adds.

“Maruti’s traditional appeal to young buyers, especially in smaller cities and rural areas, may be waning as younger consumers are increasingly drawn to more modern, feature-rich offerings from Hyundai, Kia and even Tata Motors, which are gaining traction among millennials and Gen Z,” says Vinit Bolinjkar, head of research, Ventura, an investment platform.

That’s why, at the Gurgaon launch of the Victoris, the stage was not limited to executives. Sharing the spotlight were young professionals, including a photographer, a sound engineer and a techie, who described cars as “tech labs on wheels” or rides that “match my drip”.

The presentation itself borrowed from Gen-Z slang, with words like “lit”, “vibes” and “DINK lifestyle”, making it clear that Maruti sees the next battle as one for the hearts of India’s youth.

“One-third of India’s population is young. For Gen Z, age defines them, not geography. Thanks to digital access and the internet, the gap between Bharat and India is steadily blurring,” Banerjee says when asked about the market positioning of Victoris.

The Victoris is being slotted as more than just another product. It is being pitched as the lever that could help Maruti push its overall market share closer to the once-held 50% mark.

“[In] small cars, we are enjoying a very high share already. So, our task is how to maintain this high market share in the small-car market. But [in the] SUV segment, how much success we can get is the key for improving our market share from 40% to 41% and 42%, gradually 50%...,” Maruti’s managing director (MD) and chief executive Hisashi Takeuchi said recently.

Maruti Hybrid Cars Strategy

Yet, even as Maruti makes this push, industry observers point to structural weaknesses in its premium play. One recurring critique is the extensive parts sharing across models. While this practice is common in the industry, rivals manage it more discreetly. In Maruti’s case, identical components often appear in both entry-level and premium vehicles, undermining the sense of exclusivity in its higher-end offerings, experts that Outlook Business spoke to say.

Instrument clusters, steering-mounted controls and switchgear (such as AC controls and power window switches) are often reused. For example, the steering wheel of the ₹20.5 lakh Grand Vitara feels similar to that of the ₹9.5 lakh Swift, featuring similar design and control switches. For a company looking to win over aspirational SUV buyers, this perception gap could become a stumbling block.

Maruti’s inertia has not been limited to SUVs. In the fast-changing world of electric vehicles (EVs), it chose to hold back, convinced the technology was too costly for a price-sensitive market. “Since India is a small-car market and customers have limited buying capacity, it is essential that the price of electric vehicles is affordable,” Maruti chairman RC Bhargava wrote in a magazine in 2020.

To many, this sounded less like foresight and more like a warning that EVs were not for India anytime soon. The irony was not lost, given that Maruti itself had once showcased Eeco Charge, an EV, during the 2010 Delhi Commonwealth Games.

Tata Motors took a very different view. In late 2019, it turned the Nexon into an EV, giving India its first affordable electric SUV. It was aspirational, practical and perfectly timed with the government’s push for green mobility. M&M followed with the XUV400; MG built an entire brand identity around electric, and the market began to shift.

For Tata Motors and M&M, the transition was not strategy but survival. M&M had acquired Reva back in 2010, while Tata Motors used group synergies to localise components and cut costs. With subsidies providing a cushion, both moved quickly to offset the emissions of diesel cars by investing in cleaner technologies.

The results speak for themselves. The overall PV market grew 4.8% in 2024–25, according to Fada, while the electric segment expanded by more than 17.6%, crossing the 1-lakh mark for the first time. Tata Motors, M&M and MG together sold over 95,000 units, cornering nearly 90% of the EV market.

Regulatory Bumps

The shift also gave them a regulatory advantage. Launches like the Nexon EV and M&M’s BE series built brand equity and helped meet tightening corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) norms.

CAFE norms cap the average CO2 emissions of an automaker’s fleet each financial year. The next set (CAFE-III) is expected from April 2027, for which the discussions are currently ongoing. However, individual targets are linked to the average kerb weight of vehicles sold, giving makers of heavier cars more leeway, while lighter-vehicle players like Maruti face tighter limits.

To aid compliance, CAFE-II introduced “super credits”: each EV sold counts as three vehicles, while strong hybrids count as two. These credits help in lowering the overall CO2 emissions figure. For CAFE-III, the proposed framework raises the super credit for EVs to five but reduces it for strong hybrids to 1.2, significantly shifting the incentive structure.

An October 2024 research paper published in the International Research Journal of Modernisation in Engineering Technology and Science noted that EV-led players outperformed CAFE-II targets, while those relying mainly on internal-combustion engine (ICE) struggled. Between 2021–22 and 2024–25, Tata Motors—with India’s largest EV portfolio—emitted 11–21% below target, against Maruti’s 2–11%.

In a recent analysts call, Hyundai’s Garg said the firm achieved 3.7% lower emissions than its target and expects the Creta EV to strengthen compliance. M&M, while not disclosing data, said it comfortably met CAFE-II and plans deeper electrification.

“Of course, EV is a critical component in meeting CAFE norms. There’s no question about that,” said Nalinikanth Gollagunta, chief executive of M&M’s automotive division. Parth Jindal of JSW Group had earlier told Outlook Business: “Legacy auto players don’t have any real advantage when you go into EVs because the technology is completely new and different.”

Maruti chose the opposite course, lobbying for relaxed CAFE III norms for small cars and warning that further tightening could make entry-level models unaffordable. Analysts see this as a reflection of priorities, protecting hatchbacks, rather than leading in electric.

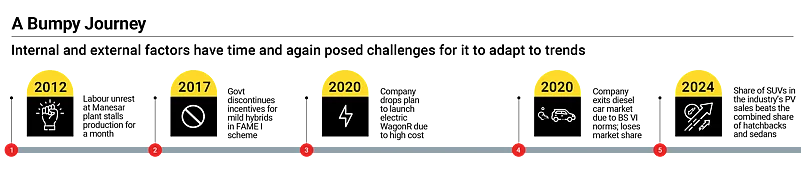

It was not the first time the company misread the regulatory winds. Hybrids once looked like a promising hedge. Maruti’s Ciaz was then the industry’s most fuel-efficient car. On the back of subsidies under the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles (FAME) scheme, it was able to beat the sales of Honda City, the segment leader at the time. However, Ciaz’s sales collapsed when mild hybrids were excluded from FAME in 2017.

The policy environment further crippled Maruti. The GST regime in 2017 taxed hybrids at 43%, adding nearly ₹80,000 to prices. As RS Kalsi, then a senior vice-president at Maruti, told analysts, the sales mix flipped almost overnight from 70% hybrid to less than a third.

Maruti Electric Vehicle Delay

That cautious stance has come at a cost. Maruti shelved its electric WagonR in 2020, and when it finally unveiled the e-Vitara last month, the rollout began with exports to 100 countries rather than a domestic launch. It was a signal of intent, but also of hesitation.

“On CNG and hybrids, there is no doubt about Maruti’s commitment. EVs, however, are still an open question,” says a former senior executive. CNG cars now account for 35% of Maruti’s sales.

The 2020 exit from diesel was also a calculated call, as Maruti argued BS VI norms would make such cars unaffordable. Yet diesels had accounted for over a fifth of its sales the previous year.

The subject continues to surface in conversations about its market share. “Diesel is still around 19% of the PV industry. So, we are operating in 81% of the market. In that market, our share is still 50%,” says Maruti’s Banerjee.

Tata Motors and M&M capitalised, strengthening diesel portfolios above ₹15 lakh while doubling down on EVs. Rivals with stronger EV bets have also shaped the policy battlefield. Knowing Maruti’s reliance on hybrids and CNG, they worked to ensure tax benefits flowed only to electric.

Earlier this year, when some states moved to exempt hybrids from road tax, Tata Motors Passenger Vehicles division MD and Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (Siam) president, Shailesh Chandra, pushed back. “It has come at the cost of suppressing penetration growth of EVs. Why digress the focus from destination technologies where you have barriers which have to be overcome? If there’s money to be put by the government, that should be on the destination technology,” he said.

“Automakers serving the most price-sensitive consumers often look defensive on regulatory change because the stakes for affordability are higher,” says Harshvardhan Sharma, group head–auto tech and innovation at NRI Consulting.

Comeback Kid

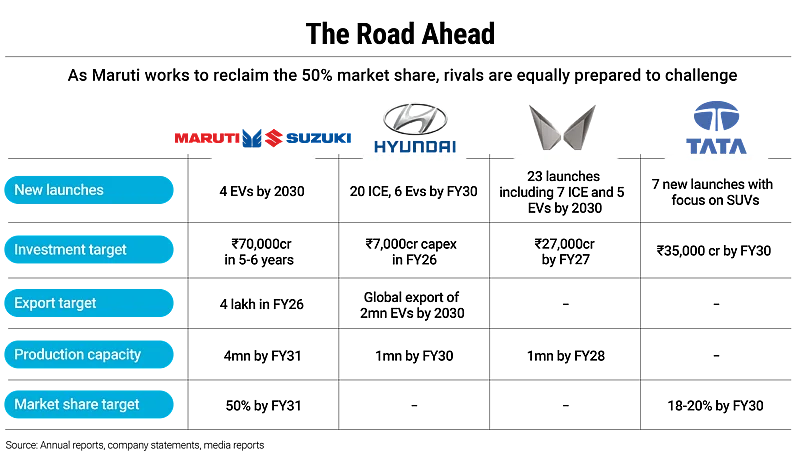

Maruti is preparing to fight back in electric. Planned launches have been cut from six to four by 2030, but the company is investing heavily in readiness: EV workshops in 1,000 cities and fast chargers every 5–10km across India’s top-100 markets.

“They will continue to leverage all their resources in terms of delivering the same brand promise to EV customers. The dynamics will change after Maruti Suzuki’s entry,” says VG Ramakrishnan, managing partner, Avanteum Advisors.

Maruti’s 2024–25 annual report projects EVs at 15% of its sales by 2030–31, or about 6,00,000 units a year. Sceptics argue it is far too late. Supporters say the delay gives Maruti time to prepare for scale, ensuring affordability and nationwide service from the start.

“Globally many OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] were late to EVs but repositioned swiftly,” says Sharma. “Consumer narratives are not fixed. What matters is execution quality and consumer value, not just the timing of entry.”

Maruti’s parent in Japan seems concerned about the changing business environment in India and intensified competition in EVs. “[We] need to rethink strategy,” Suzuki Motor Corporation had said in February this year in its mid-term management plan for 2024–25 to 2029–30.

But Maruti has weathered tough times before. In 2011–12, labour unrest at the company’s Manesar plant paralysed production and slashed its market share to 38.3%, down from well above 45% the year before. For the first time in decades, the market leader looked vulnerable. Some wondered if Maruti’s dominance had peaked.

But Maruti came back with a vengeance. Once workers returned to the shop floor, the company launched a barrage of models aimed at every price point and customer segment. The Alto 800 and Baleno shored up its small-car fortress, the Dzire facelift renewed its grip on sedans, the Ertiga brought multipurpose vehicles into middle-class homes and the Vitara Brezza finally gave Maruti a credible SUV.

By 2017–18, the results were unmissable: market share had soared back to 50%, and annual sales crossed 1.5mn units for the first time in its history.

Indian Auto Industry Trends

This resurgence was built not only on new launches but also on scale and reach. Capacity expansion gave Maruti the firepower to flood the market, while its unmatched sales and service network ensured penetration where rivals struggled. Growth came faster than the industry could keep pace with.

The company also adapted to shifting fuel economics. As the gap between petrol and diesel prices widened, diesel demand spiked. Maruti leaned on Fiat for engines, ramped up supply and saw volumes of the Swift, Dzire and Ertiga swell on the back of their diesel variants.

“Maruti never plans for small numbers,” says IV Rao, former executive adviser, engineering and director at the Maruti Centre of Excellence, a skills-training hub.

He explains that Maruti’s mass base allows it to spread the high cost of technology upgrades across millions of cars, recover investments faster and keep prices competitive, a structural advantage that is difficult for smaller rivals to match.

It was a textbook comeback, and one that restored Maruti’s reputation as an automaker that knew how to fight back when cornered.

For all the pressure Maruti faces, it still sits at the heart of Indian motoring. Four out of every 10 cars sold in the country carry its badge, a level of dominance rare anywhere in the world. In Europe, Volkswagen controls about 25% of the market; in Japan, Toyota’s share is roughly 30%.

“If it was only 25%, I would have said Maruti Suzuki has lost dominance. But at 40%, it is still a dominant player that can alter the market direction through their investments,” says Ramakrishnan of Avanteum Advisors.

Hyundai, a distant second with 13.9%, has struggled to scale despite aggressive launches. Tata Motors and M&M have inched upward with their SUVs, yet Maruti continues to tower above. The aura of inevitability may be fading, but few doubt its ability to find its rhythm again.

Fresh Beginnings

Industry veterans often recall one such turning point: the launch of the Swift in 2005. More than a hatchback, it was a statement. Built with global inputs, tied to a Bollywood campaign through Bunty Aur Babli, and packed with features that redefined expectations, the Swift gave Maruti Suzuki aspirational appeal.

“The Swift was designed to connect with a new India. It was a breath of fresh air in the Maruti image,” says Avik Chattopadhyay, founder, Indian School for Design of Automobiles.

The difference today is stark. Then, Maruti was fighting in its comfort zone of small cars. Now it must contest SUVs, EVs and an unpredictable regulatory landscape. “In a fast-moving, tech-driven market, you’re better off disrupting yourself than letting somebody else disrupt you,” says Rajendra Srivastava, Novartis Professor of Marketing Strategy and Innovation, and former dean, Indian School of Business.

Signs of adaptation are visible. The company is pushing into electrification, hybrids and new platforms while sharpening its focus on SUVs. Its latest SUV, the Victoris, will be sold through Arena dealerships even if it cannibalises the Grand Vitara. Arena’s vast reach is seen as a bigger advantage. The e-Vitara, Maruti’s first electric SUV, is set for launch in India this financial year.

“If it had not been for the reputation of quality and the effectiveness of the dealership and repair networks in the past, they would have lost share a lot faster,” Srivastava says.

But rivals are not standing still. Hyundai is preparing its biggest product offensive since entering India, with six EVs and 20 ICE models over the next five years. M&M, already the SUV leader, plans five EVs and seven ICE models by 2030.

Maruti is countering with an SUV-heavy line-up and is studying a move into the premium SUV segment, where it has no presence today. “To maintain our leadership, we have to be No. 1 in SUVs also. We cannot ignore this market,” Maruti’s Takeuchi said recently.

Race is On

Exports are another buffer. Overseas sales have been growing nearly 27% annually, allowing Maruti to overtake Hyundai as India’s top exporter with over 40% share of India’s PV export market. Most of the planned 67,000 e-Vitaras in 2025–26 will be exported, where demand and margins are stronger.

“Through export of its EV, Maruti is doing what India wants to do: make the country an export hub,” says Gaurav Vangaal, associate director at S&P Global Mobility, an automotive-data provider.

Despite the loss of market share, investors remain confident. Maruti’s stock has risen 24% over the past year.

“Maintaining a 50% share is increasingly difficult in India’s evolving automotive landscape. Nonetheless, Maruti has sustained over 40% for years, which is impressive,” says Ventura’s Bolinjkar.

Policy tailwinds are also shifting. Experts believe Maruti will be among the biggest beneficiaries of the government’s production-linked incentive scheme once the e-Vitara enters production.

The Union government has finally understood the importance of growth in entry-level cars to boost manufacturing. It has cut the GST rate to 18% on small cars, which could revive Maruti’s strongest base.

The timing is critical. The company has committed over ₹70,000 crore to nearly double capacity to 4mn units in five years, far ahead of Hyundai’s 1mn by 2030 and M&M’s 1mn by 2027–28. “Recent actions like reduction in both direct and indirect taxes, and accelerated interest-rate cuts to stimulate domestic demand, will eventually boost the manufacturing sector,” Takeuchi said last month.

While GST 2.0 will reduce vehicle prices, the income-tax rebate will give buyers surplus money for down payment and the repo rate reduction will reduce EMI value, Banerjee says. “All these will aid customers to upgrade to a car.”

Few doubt Maruti’s ability to shape the industry’s direction. “Maruti’s actions will determine how India progresses on policy implementation and industry growth,” says Ramakrishnan.

The jungle it once ruled has changed. The incumbent lion remains the king, yet the roar of challengers grows louder.