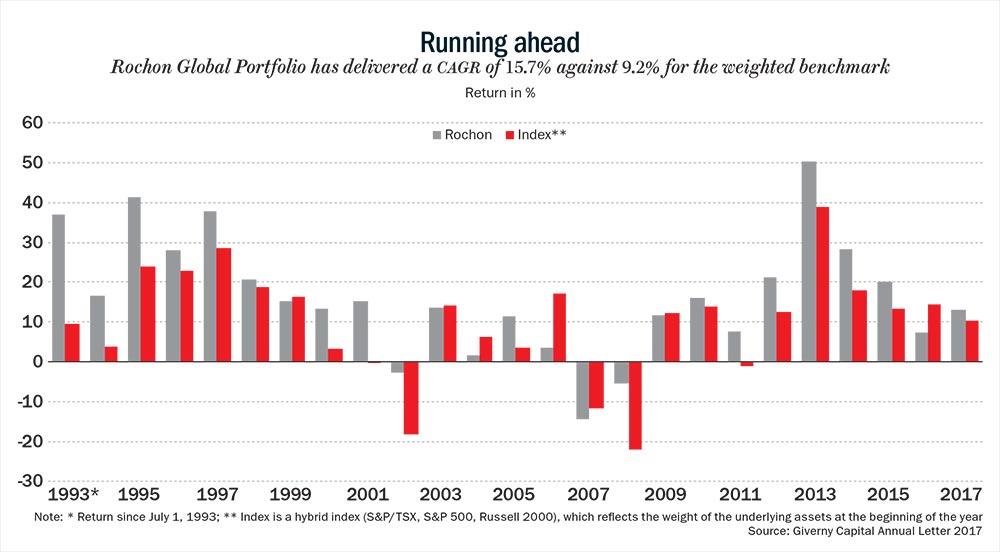

A disciple of Ben Graham and Warren Buffett, Canadian value investor François Rochon founded Giverny Capital in 1993. An art connoisseur, Giverny is Rochon’s tribute to the hometown of his favourite artist Claude Monet. The influence of art is evident in Rochon’s investing approach; he looks for beauty in a balance sheet and identifies great managers like he scouts for contemporary artists. Just like artists are independent in their thoughts and actions, Rochon believes so should an investor. If the stock selection process is rational, investment returns will eventually follow, believes the art buff. Not surprising that an engineer by education, Rochon has turned out to be an exceptional investment manager with his portfolio yielding 15.7% CAGR since inception. In a free-wheeling chat, Rochon speaks about his hits and misses and elucidates on why investing is far from easy when errors of omission often prove more costly than errors of commission.

How do you assess a management as you had mentioned that if a management makes a decision that you don’t agree with, you sell?

It is largely subjective and also involves fact gathering. We read up annual letters of the past five to 10 years to see what the management had stated and what they did, besides looking at how they compensate themselves. We prefer managements that own a higher stake in the company. But the most important criteria is the culture of the company and how managements behave during recessions, what kind of acquisitions they made in the past. But at the end of the day it’s a judgment call.

Do you also meet managements? Many private investors have minimal interaction with managements as they believe it will cloud their judgement.

We do try to meet them on most occasions. But, for example, you don’t need to meet Bob Iger of Disney because you have enough to read up on him, lot of interviews on the Internet and in the magazines. However, it’s important to meet managements of smaller and lesser-known companies.

Are you size-agnostic? Do you want companies to be of a certain market cap before they come up on your radar?

Usually, our threshold is $1 billion. Since we manage about more than a C$ billion, companies have to be of a certain size for us to invest in. But a billion is not really that huge as there are over 2,000 companies that have a market cap in excess of a billion. We tend to wait for a small company to achieve a certain size and profitability so that it does not remain a micro cap.

One of the reasons you sell is when you find something better. How do you decide what you plan to buy is better than what you hold?

The first thing we expect is a higher return over the next five years. For example, if between companies A and B, B can earn 16-17% annually against 10-11% in A. Besides potential return, we favour investment which carries a lesser risk. So, it’s not only about return, but also how you assess the risk.

Can you explain that with a recent example?

Last year, we reduced our holding in Disney because we felt the fundamentals were not as strong as it was a decade back mostly because of ESPN. It’s a slightly maturing business. Hence, we trimmed our weight in Disney and invested in Edwards Lifesciences as we felt the company had stronger fundamentals. Though it had a higher P/E multiple than Disney, it had stronger growth prospects.

You have articulated your investment philosophy as one where you look at a company which is a market leader led by a capable management team, enjoys high return on capital, high growth in earnings, and a modest debt-equity ratio. But when a company displays all of these qualities, you hardly find stocks that are mispriced. How do you then find value?

It’s a challenge. When you choose to invest in the stock market, you have to decide as to what is already factored into the stock price and what is not. If you believe a company will grow its earnings by 15-16% over the next five years, you don’t want its P/E multiple to shrink in the future because the return on the stock will be lower than its intrinsic value growth. Hence, it’s a challenge finding companies that have superior growth prospects and superior business model, which is also sustainable. The competitive advantage and growth prospect should be sustained over the next five years because if you pay 20x and earnings double in five years, but if the multiple shrinks to 15-16x, you would end up with a return of just 9-10%. Ideally, you wouldn’t want the multiple to shrink or, at the very least, stay at the same level. If it stays at the same level you have a return equivalent to the company’s intrinsic return.

So, we try to find companies that can sustain their multiples. We buy what we believe is a discount to intrinsic value in terms of the multiple. So, if we are right on the long-term fundamentals, then the multiple will only expand. But the key thing is to find the margin of safety. We want margin of safety in the way we assess the competitive advantage of a company and its growth prospects. We also want margin of safety in terms of the multiple. Any company that we pick has to be undervalued — either the multiple is too low or the growth prospects are so solid that even without an expansion of the multiple, we will earn a superior return. While there are many ways to earn a superior return, the best way is to find companies that will grow their intrinsic value at a rate higher than the average. We hold stocks for years together as they eventually follow the intrinsic increase and earnings per share. But the challenge is not only about finding companies with solid growth prospects but also finding those whose valuations don’t fully reflect their growth potential.

Have there been occasions where you ended up over-paying?

Of course, I made that mistake quite a few times and also the mistake of not paying the right price. In some cases, I failed to assess the growth prospects correctly but probably the worst mistake would be of avoiding paying a little premium for a high quality company. If you find a company that will grow 1,000% over a decade and don’t buy it because the multiple is too high, well, it’s a big opportunity cost. It’s a big omission mistake. That’s much more costly than overpaying a little bit and losing 25-30%.

You did not invest in Starbucks because it was trading at 40x. If you were to go back to the same position, how would you have justified investing in the stock?

It’s easy with hindsight, but let’s just assume. Nearly 25 years ago, I don’t know exactly how many outlets Starbucks had, but let’s assume it had 500 coffee shops. You could envision that someday it will be 25,000, and that’s a 50x increase. So, if revenue increases 50x and earnings increase 50x in 20 years, then the stock at 40x doesn’t discount this kind of growth. So, that’s the key. If you can find a company that offers 5,000% increase in earnings over two decades, you can even pay 100x and it will prove to be a good investment. So, it’s all about finding those rare companies that offer a huge growth potential, strong management and a strong brand that warrant a very high multiple. So, when you are valuing a company, what really counts at the end is what kind of growth it would enjoy over the next five, 10, 15, or 20 years. That’s not easy to assess. But on the rare occasions that you find a company with such a strong growth potential, be ready to pay a multiple that wouldn’t make sense for a value investor. If you have some vision and fortitude, you can go beyond today’s high valuation and see that the growth potential justifies paying such a high multiple. But finding companies that can grow their revenue and profit 50x over 15-20 years is very rare. If you find one and are pretty confident about it, then with hindsight, the only intelligent thing to do is to buy and hope for the best.

Besides Starbucks, what were your other big mistakes, and what did you learn from them?

We invested in Google in 2011 though we should have invested in 2004 when the company went public. Again with Apple, when the first time I saw an iPod I should have realised its growth potential. Then there are some stocks that we’ve owned for seven-eight years such as Dollarama, a Canadian leader in dollar stores. At some point, the stock got a little expensive and we sold a few shares. The stock went up 1,200% in eight years. We should have held every single share that we owned and our partners would have been much richer today. So, the key thing is when you find an outstanding company not only do you have to buy it but also learn to hold it. And that’s the hard part because you have some inclination of wanting to manage the risk when it becomes a little expensive or ends up occupying a larger weight in your portfolio. That can be a mistake.

Any other lessons?

In the annual letter I have mentioned about Intuit and FactSet Research. These were great companies that I wasn’t ready to pay the right price as they seemed too expensive. But I should have realised that these were very strong companies and, hence, command higher multiples. The biggest mistake was not paying a higher price because I wanted to be very prudent. But sometimes prudence in owning outstanding companies is not necessarily about buying them cheap.

You drew a parallel between Disney and companies that own oil fields, stating that just like one can get oil out of an oil field for 50 years so is the case with Disney’s characters. But investors aren’t giving Disney as much credit for the properties or the assets that it owns. In such companies how do you evaluate the growth potential that can be unleashed over a seven-year holding period that you usually look at?

Disney is a very different company from what it was a decade back. Following the deal with 20th Century Fox, ESPN’s contribution will reduce as it accounted for 40-50% of Disney’s earnings. ESPN was an incredible business for several years but then the movie business isn’t as great a business as ESPN was. So, though the business model is less dependent on ESPN now it is not as strong as it was 10 years ago. I don’t expect Disney to grow at the rate as it did between 2005 and 2015. From 13-14% annual growth rate, the growth will be around 8-10% now. Also, you never know how things could turn out with the new additions to its brands with Star Wars, The Simpsons, all movies of Pixar, all Marvel characters, the classic Mary Poppins, and Alice in Wonderland. I believe Star Wars is a great acquisition, and Disney is finding ways to expand its franchise and widen its revenue streams. It also has an aggressive business plan in the streaming business with Hulu. Hence, I think the growth prospects are better over the next five years than what it was two years back when earnings were growing slowly. Going forward, the stock should do much better than what it had over the past couple of years. If Disney can grow 9-10% annually, then at 14x the stock is under-valued but not as under-valued as it was when we purchased it in 2005.

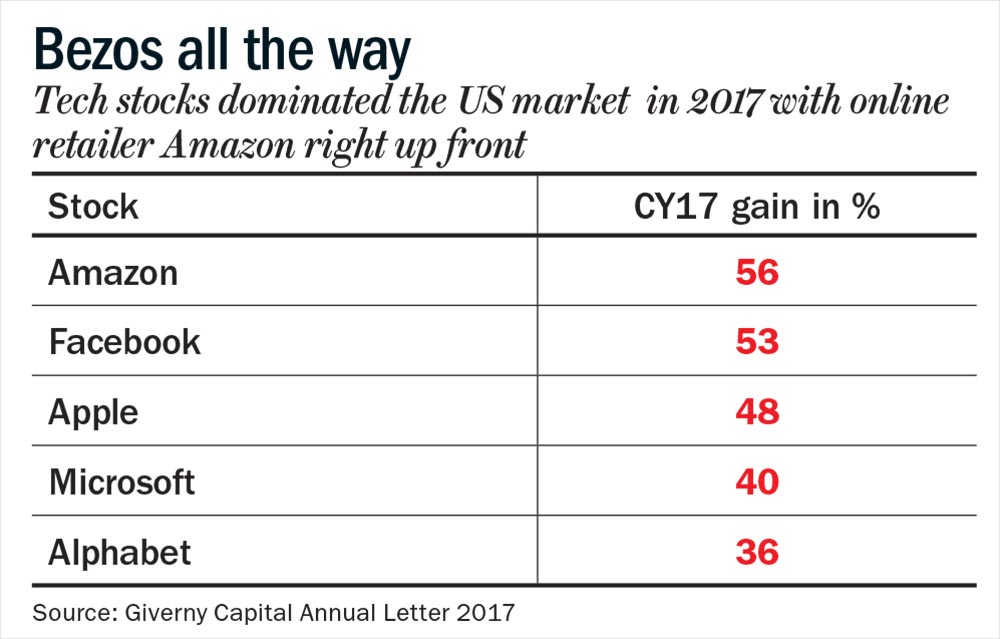

How about stocks such as Walmart? At a time when online retail is taking off, how do you recognise the moat in these companies? Amazon owns 4% of the US retail market. Do you really see moat in these companies that can get them re-rated at some point in time?

Amazon is a terrific business that is extremely well managed. It is very aggressive yet focused on the long term and, hence, can accept a lower short-term profitability for longer-term rewards. Very few companies have these kind of time horizons. We’ve owned Walmart a few years back but I wouldn’t own it today because it is going to be tough to grow revenue and sustain margins. I don’t think it is going to be an incredible investment and that applies to other retailers as well. I think Dollar Stores in general are a little bit shielded. TJX also has a niche. Lululemon has a strong brand and sells online to customers but I don’t know how well shielded it is from Amazon. You can find companies that have found a niche in the retail space even though Amazon is a strong competitor. Traditional companies such as Walmart, Target, Best Buy or Big 5 Sporting Goods will do well. But it’s hard to see where Walmart will be in 10 years. It doesn’t necessarily mean it won’t do well, it’s just that it is too hard for me to predict. When it’s too hard to predict, it just means that we won’t make an investment. We want to make investments where we feel confident in assessing the next five to 10 years. It doesn’t mean we will be right. It’s just that we are more confident about the long-term nature of the business.

Disney was a big winner. What were the other winners and what did you learn from them?

We did very well with O’Reilly Auto Parts. We discovered it because we were following AutoZone and we are talking about 14 years ago, in 2004. I felt O’Reilly had better growth prospects. It had better stores and better distribution centres. I went to visit them in Missouri and was really impressed with the management. AutoZone was probably 10-12x and O’Reilly was 16-17x. I paid up a little higher for O’Reilly and it turned out to be a great investment. It was the same thing with Bank of the Ozarks. We purchased the stock 12 years back at 16x earnings. For a bank that was on the higher side. While today it is a little more common, in 2006, there weren’t many banks that traded at such high multiples. Most of them traded between 12x and 14x. It’s been a very good investment for us as earnings have grown 18-19% annually since then. So what I’ve learnt is to focus on quality, on companies that are not as well-known and are perhaps bigger players. But as Peter Lynch said, the key is not to cut the flowers and water the weeds. So, you have to keep companies that are doing very well even if, at some point, it looks a tad expensive relative to other stocks in your portfolio.

You have mentioned that investing is imprecise and one is wrong 40% of the time. But how do you ensure that you don’t get killed by that 40%?

Well, it’s about managing risk. Every little thing that reduces risk improves your odds of success. So, you want companies that have a strong balance sheet, that have good margins, have a competitive advantage, and do things every day to increase their competitive advantage. You want companies that do not sell a commodity, but have a distinctive product. You want managements that do intelligent acquisitions; that manage capital properly like buying back stocks when they think a stock is undervalued. So, all of those little things reduce the risk and improve the rate of success. However, that doesn’t mean a company with a sound balance sheet, great management, and solid product won’t prove to be a mistake. There are so many things that can change — the industry changes or a new competitor disrupts the industry. Some things will turn okay and some will disappoint. For example, we owned Bed Bath & Beyond from 1998 to 2005. We sold the stock 13 years ago. Today, it’s a poor investment but during the period that we owned the stock, it was a dominant business. You have to accept that even though you work very hard at gathering facts, you cannot always know the future for certain. You have to accept that you will face failures and that’s just a part of being in business. You will do better with a success to failure ratio of 60% to 40% than 50%. You cannot have 100% success, even 80% is impossible to attain.

You also have this ‘Rule of Three’. How did it get formulated?

The Rule of Three is basically about having realistic expectations and I came up with that 17 years ago. I had studied the period from 1993 to 2001 and realised that once in three years, the stock market went down 10%, and once in three years, we underperformed the index. Also, about 33% of stocks we bought didn’t turn out as expected. I feel that stating that rule to yourself, to your business partners and clients will result in realistic expectations going forward. During tough years and tough investments, you are better prepared because you know that it is inevitable and in such circumstances you are psychologically well-prepared. Just like Charlie Munger says, “The success to a marriage is low expectations”, so is, probably, realistic expectations the key to successful investing.

At times you tend to look outside of your investment framework and take a judgment call. Under what circumstances does a judgment call overrule your framework?

Over the years I have made investments that were a little different from the framework philosophy. Sometimes it worked well and sometimes it didn’t. That one that didn’t work well is Valeant and it was really a judgment call on the management. We were lucky because we doubled our money but it was a big mistake. Since it was a different kind of investment, we didn’t want a big weight in that investment. So, when the stock crossed the 5% threshold in our portfolio we trimmed it. So, one reason we avoided big losses was because we kept selling the stock on a few occasions. Our latest investment in Liberty Media Formula One is a different kind of a situation. The company is not very profitable but it’s really about the management and also how strong the Formula One brand is. It’s still early days but we believe that over the next five to 10 years, it will blossom into a much better business as it has a strong brand, a strong business and a new management.

In 1998, we invested in Expedia when it was barely profitable. It turned out to be a very good investment. Though I didn’t really buy the stock in a large quantity it was an example of entering into a company a little earlier than I usually would. In 1998, I had also invested in a closed-end Fund, the Templeton Dragon Fund. We don’t usually invest in funds but invest in companies. But I knew Mark Mobius and it was also around the time that the Hong Kong and Chinese markets were very depressed. It was about buying a great fund at a substantial discount to its intrinsic value. We do such investments when we believe it’s a strong opportunity.

There is a very fine divide between conviction and foolhardiness. So, what is your checklist to course correct when you make a mistake or when an investment starts to go wrong? You have this analogy related to cooking a frog. Can you explain that with an example?

Usually when results are not very good or disappointing, many a times the stock will go down and appear under-valued. That will make you believe that the price discounts all the news. But sometimes the bad news continues. So, that’s the analogy about the frog. When you boil a frog you put it in a mild or cold water and slowly increase the heat. The frog thinks it’s a temporary problem and believes the water will get back to cold temperature soon. Even if it does, it’s too late as the frog cannot jump out of the hot water. It’s the same thing with stocks. You may think the bad quarter or problems are temporary and, hence, feel the stock is so under-valued that it discounts all the problems. An example of that would be IBM. We purchased the stock, probably in 2011 or 2012. We held it for three-four years and during that period earnings didn’t grow and, at some point, earnings stopped growing. The P/E multiple never increased and we decided that we had to sell it and buy something else. Many years ago we invested in Fifth Third Bank when the stock looked undervalued as earnings kept going down. At some point we realised that we made a mistake and we sold it.

As an investor you have to recognise mistakes early instead of waiting for two-three years. When you realise that you’ve made a mistake, sell as fast as you can. Yet, at the same time don’t sell too soon and in a situation where the problems are indeed temporary, where after a quarter or two the situation would have improved. In short, it’s all about judgment as you cannot correctly predict the future. At the end, if you are right two out of three times, probably that’s an acceptable outcome.

Finally, what are the parallels between a great painter and a great investor?

When you want to build something or do something original, you have to develop your own way of seeing things. You have to create your own style. You don’t care what others think as you are not trying to copy or imitate others neither are you trying to please anyone. Like a painter, you are independently analysing facts and assessing reality, and doing what you believe is the best path. So, it’s really about thinking independently and that’s not an easy thing to do. It’s sometimes hard to go against the trend and stick to your guns.