There are likely to be fewer illnesses from contaminated drinking water in some 25 villages in Odisha this monsoon. Villagers, who were drinking water infected by e-coli colonies, can now go to the local kirana store and pay Rs.2 for 10 litres of purified drinking water. Or else, they can have jerry cans of water delivered to their homes for Rs.3 per 10 litres. Paul Polak, the 79-year-old founder of Spring Health International, the company that sells this water, is sometimes accused of profiting from the poor.

But after 25 years of working with underprivileged communities across countries like Cambodia, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Nepal, Vietnam, Zambia and Zimbabwe, he has discovered that building a profit-oriented enterprise is the only sustainable way to pull the poor out of poverty. In the past three years, he has worked to create companies that have the objective of reaching drinking water to 100 million customers with incomes of under $2 a day.

“Achieving scale is the biggest unmet challenge in development today,” Polak says. “What we have learned, not only in India but in 15 other countries, is that you can achieve scale only by unleashing the energy of the market place.” Now that Spring Health has tested out its pilot, it’s ready to roll out. Polak wants to sell water through kirana stores in 10,000 villages in the next three years. He needs to raise $2 million for this and is in India to talk to potential venture capitalists about it. Polak feels that the business model is compelling enough to attract regular VC funds but, at this early stage, chances are that he will need a fund that’s willing to ignore immediate returns and focus instead on the social impact of Spring Health’s business.

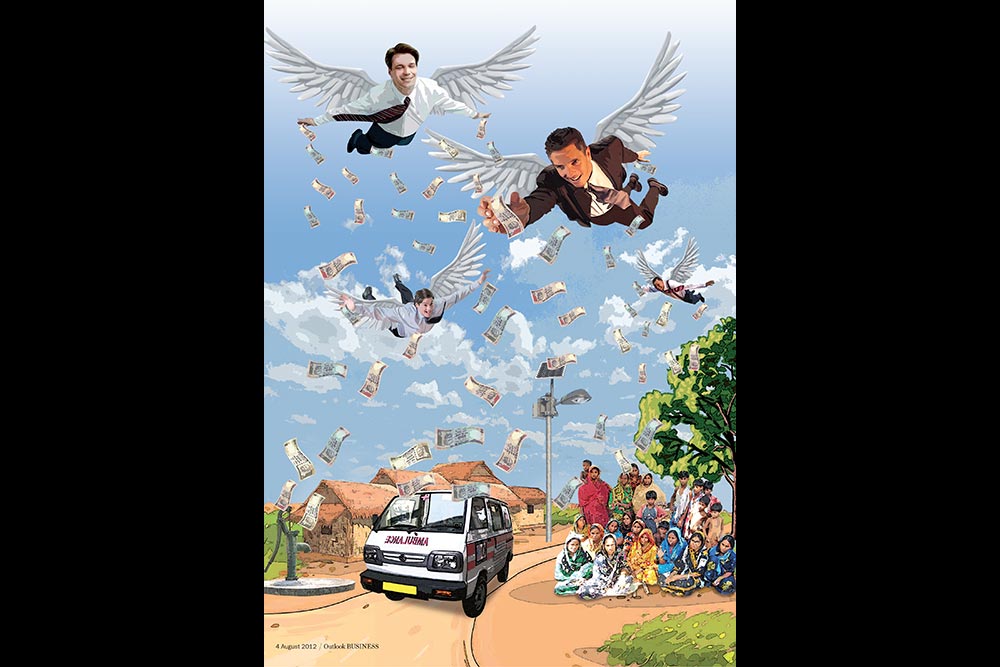

Polak is not alone. In the past decade, India has seen the genesis of a new kind of businessperson who provides basic facilities — from solar electricity to education to ambulance services and green power — to a large customer base that has largely been ignored so far. This customer base — poorer than the middle class, and living above or below the poverty line — was expected to be served by the government.

The lack of development has seen new entrepreneurs seeking to close the gap, not philanthropically but with a sustainable and profitable business model. Once the model is set up, the next step is to secure capital and expand the business. Enter social venture funds or, as they are now called, impact investors.

Impact investing in India took off early in this millennium with the advent of microfinance companies. While their early activities were largely in the area of financial inclusion, impact investors are now looking at the gamut of businesses, including healthcare, internet and technology, agriculture, sustainable power generation and education. However, even though the market that exists at the bottom of the pyramid (BoP) in India is immense, not much capital has flowed into it.

From 2007 to 2011, over $1.3 billion was invested into early-stage deals in India. However, most early-stage ventures that received funding since 2007 did not focus on the BoP market — in fact, the ventures that focused on the BoP market received less than $300 million.

That may be, finally, set to change, surely if slowly. The early adopters of impact investing were government-run development financial institutions but, today, a whole range of investors are participating in the social ventures sector. This includes private foundations such as the Omidyar Network as well as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, large private institutions like JP Morgan and Citigroup, as well as boutique investment funds.

Down under

Even though BoP has been a buzzword since CK Prahalad first wrote about it in 1998, it is only now that its financial potential is being unleashed. In India, the largest potential for growth is seen in providing low-margin, high-volume products to the 450-600 million people who live on under $2 a day. The opportunity in just linking up a distribution system here is very high. Look at Polak’s villages in Odisha — they are settlements with 1,000-2,200 homes. The kirana owner makes trips to the nearest town every three days in order to stock up 80% of what he sells. Spring Health’s associates visit the villages once in three days. Soon, they will be carrying with them stocks of all kinds of products for these stores. And when they come back, they would have aggregated products from the villages that can be sold at the nearest town.

“These villagers make Sambhalpuri saris, for example, and stores like Big Bazaar and Mother Earth are interested in retailing them,” says Jacob Mathew, CEO, Spring Health. “Aloe vera, which is a hardy plant, can be grown in the region and its gel extracted and sold to manufacturers of cosmetics. There are various options.” In just accessing these villages, the potential opportunity for diversification grows significantly. “There are concerns like last mile distribution, but they will be sorted out sooner than later,” says Polak. “We are trying to figure out various ways to address this.” Once the water purification enterprise shows real results, it will not be long before large corporations and multinationals tread down the same path. Impact investors will then make good their investments several times over.

Funds that invest globally also bring with them the advantage of taking the products of these social enterprises to foreign markets. Ennovent, for example, is an impact investor that funded an African enterprise, Barefoot Power, in 2011. Ennovent is a company that has developed low-cost rechargeable and solar-powered lamps at a price point that has attracted many customers living ‘off-grid’ to buy a lamp to replace their kerosene purchases. It is now partnering with Barefoot Power to venture into India and reach out to 400 million people who live without electricity in the subcontinent.

Basically, social venture funds have one primary criterion for deciding on investments, and that is social change. But there are several conditions that funds look for even within this. Jayant Sinha heads the Omidyar Network in India, an impact investing fund set up by Pierre and Pam Omidyar. Pierre Omidyar started Ebay and used the money that he earned when the company went public to set up Omidyar Network, a philanthropy-focused investment firm. “We have only one bottomline and that is social impact,” Sinha says. “What will be the company’s impact on the lives of people and how many lives will it change?” But once the social impact is assessed, the enterprise is also tested for its capability to build scale. If companies are unable to scale up, they find it difficult to eventually attract commercial capital.

Early stage funding?

Even as late as 2009, social enterprises were finding it relatively easy to get early-stage funding. However, after experiencing several failures, funds are now increasingly cautious. Polak says that this is a trend he sees around the world. “Business venture capitalists find the model attractive but they are less motivated to come in at early stage,” he says.

“Once the enterprise is established, everybody wants to jumps in.” A case in point is Ziqitza Healthcare, a company founded by five friends when the mother of one of them faced a critical medical emergency — it prompted the group to think about the pathetic state of ambulance services in India. In 2005, they started 1298, an ambulance service in Mumbai, where the poor who go to government hospitals were entitled to free service, and the affluent who preferred private hospitals paid for the service.

After several rounds of talks with profit-oriented venture capitalists, none of which yielded results, they finally managed to raise money from Acumen Fund, an impact investor. Today, Ziqitza has investments from HDFC and IDFC, as well as India Value Fund Advisors and the US-based Emergency Medical Services Corporation. The company now runs ambulances services for the government in Kerala, Rajasthan, Bihar and Punjab, as well as private services in Mumbai, Punjab and seven districts of Kerala.

Acumen Fund, one of the better known social venture funds in India, has been investing in areas such as agriculture, healthcare, energy, water and low-cost housing for the past eight years. Acumen is funded by donations from philanthropic organisations like the Rockefeller Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, as well as individuals. When Acumen began investing in India seven years ago, it was willing to take a risk on companies whose products or technology was untested.

Today, the fund is more worried about the enterprise’s distribution strategy and scalability. Ankur Shah, Acumen’s interim India director, says, “Now, getting the product to the market is the challenge and we are focused on last mile distribution risk. That’s what we want to solve.” As a result, Acumen wants to make sure that the companies it is backing have already proven their products and have demonstrated some ability to get their products to the market. Despite this, when measured against conventional venture funding norms, social funds still fall in the realm of early stage. Most investments are around $1 million. Acumen Fund, for example, plans to invest Rs.20 crore every year over four or five enterprises.

Patient capital

The road to exit social enterprises is a long and often rocky one. This is another reason that explains the larger interest of impact capital over regular venture funds. Social funding itself comes in two shades — those who prioritise social impact over financial returns and vice versa (Acumen and Omidyar belong to the former while funds like IGNIA, and investments by the likes of JP Morgan and Prudential, belong to the latter). Overall, five to seven years is seen as a reasonable time to exit social impact funding (as compared to three to five years in normal VC funding). “However, what we have realised is that we need to be even more patient,” says Acumen’s Shah. “We have been invested for seven to eight years. Some of these [enterprises] are ready for exits now. But it ain’t over until it is over.”

Funds that prioritise social impact tend to be invested for as long as it takes to prove the business. The actual time frame also depends on the class of funds invested. Debt investments could last as long as 10 years and as short as five, whereas equity investments are open-ended. And while there are examples of individual enterprises that have failed, there aren’t any funds of significant size that have folded up so far. The industry is less than a decade old in India and those stories are likely to play out after a couple of years.

About those returns

Unlike regular investors, impact investors seek return of capital rather than return on capital. While funds would be happy with a 10-14% return on investment (against a 14-18% that regular funds seek), the important criterion is that they get their capital back that can be deployed in another business. “On a portfolio basis, we are hoping to return our money [capital],” says Shah. “The distinction to draw is between philanthropy, which gives you a negative 100% financial return, and commercial investment that gives you potentially 20-30% financial return but no social return. We are hoping for 0% financial return but a significant social return.”

However, the need to have some sort of standardised evaluation criteria to measure social impact is increasingly being felt. A new approach that is holistic and transparent is being proposed. It’s called the Global Impact Investing Rating System (GIIRS) and it’s backed by B Lab, an independent non-profit organisation. The GIIRS will be like the rating given by Morning Star to mutual funds. It provides funds with an impact rating, giving them one to five stars based on an assessment of their companies’ impact practices and performance. It’s a survey with about 160 questions divided into five areas of impact: governance, workers, community, environment and focus of the business model.

A company can do well in some areas and perform weakly in others, but to get a 5-star rating, it must have reasonably good practices across these categories. The rating gives donors and investors in these funds an assurance of how the fund is meeting its objectives. About 25 funds have been rated so far.

It’s still complicated

Despite the large scope of growth for both social enterprises and impact investments in India, certain challenges remain. “Challenges are three-fold,” says Omidyar’s Sinha. “First, the supply of entrepreneurs is very low. Entrepreneurship should be seen as an exciting career track in India but we have more careerism and less entrepreneurship,” he says. The second problem is that in India there aren’t any domestic financial institutions that are willing to invest in this sector. “Right now, 90% of the market for impact investing in India comes from outside India. Third, there is not enough venture debt available due to low return and high gestation,” Sinha says.

Even if funds find enterprises with a strong leader, finding people to work in these organisations is another challenge. Then there is the continuous need to train the staff. Social funds usually take a position on the board of the companies they are invested into, so that they can keep a keen eye on their operations. Acumen’s staff meets with each of its investees at least once a month.

Despite the challenges, funds with enormous corpuses are standing by, waiting for the right opportunities. Omidyar Network is looking to invest $100-200 million in the next few years. A JP Morgan report assessed the size of impact investment to be $400 billion to $1 trillion worldwide in the next decade. Much of this will be targeted at developing countries.

Where impact investing goes, corporate money is quite likely to follow. Once Polak fixes his last mile issues, he is certain that the multinational consumer goods giants will beat down the same path. And though Spring Health is dealing with what we in urban India take for granted, it’s perhaps not overtly optimistic to imagine that in a few decades, kirana stores will be stocking glistening bottles of drinking water in all the obscure villages of Odisha.