“Now the trumpet summons us again—not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need—not as a call to battle, though embattled we are—but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle…”

Jack Kennedy’s words ring true more than 60 years after the 35th US president uttered them. Kennedy was referring to the Cold War that his country waged for over four decades against the erstwhile USSR. Ironic that his words are back to haunt his country as the US global supremacy is challenged by Russia, yet again, albeit reduced in landmass, influence and might, but exaggerated by Putin’s ambition. However, Russian president Vladimir Putin is not alone in his efforts to thwart America’s hegemony.

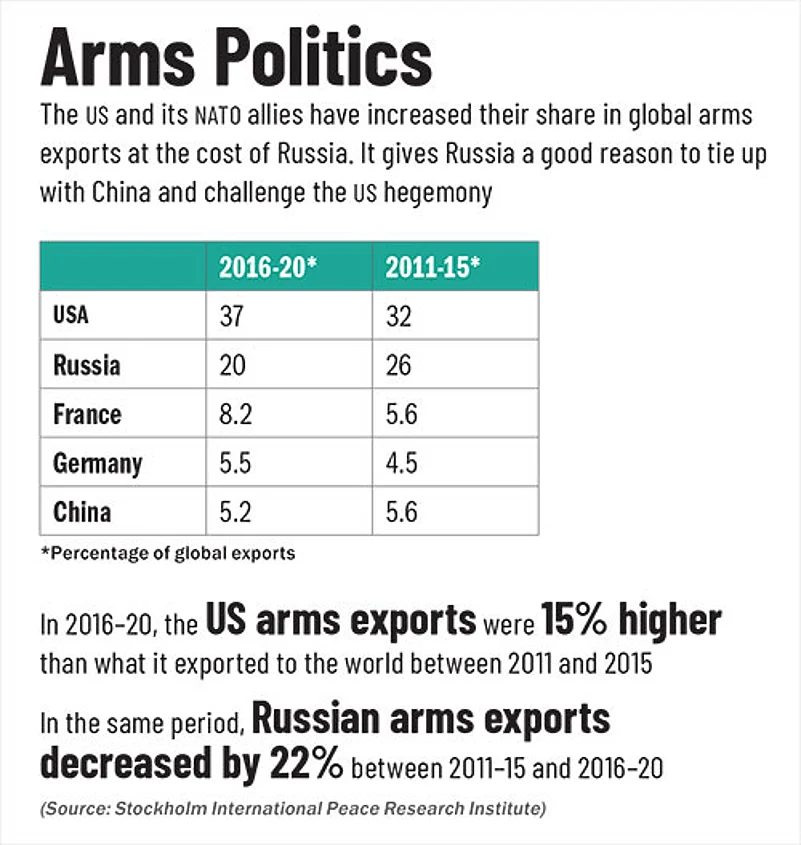

As the US diverted its focus from containing rivals, first with its war against Islamic terrorism in the aftermath of 9/11 and then with the economic fallout of the 2008 financial crisis, the Chinese dream of a new global order gathered steam. In fact, the Asian superpower poses a bigger challenge to the US-centric global order than Russia can ever do despite the Ukraine war. While Kremlin has been using sale of arms, commodities, intelligence and proxy wars to keep its influence over east Europe, the Middle East and Africa, China, through coercion, investment and diplomacy, has already gained geopolitical primacy in Asia, almost pushing the US out of the equation.

“The global order, or the US-led liberal international order, that we have known since 1944 is fast eroding. Twenty-one per cent of global GDP has changed hands from developed to emerging economies since 2000 (14% of which has gone to China). It means that the West cannot dominate all global institutions and rules any longer. But, the US itself under Donald Trump came to question its leadership role in that order and decided to give up on all institutions and global rules it created,” says Yves Tiberghien, professor at the Department of Political Science, University of British Columbia.

Looking at the US response to its diminishing global leadership, it is unclear if America is ready once again for the “burden of a long twilight struggle”. Taking off from Trump’s disinterest in American leadership in matters of world importance, President Joe Biden has already called for “making in America”.

“The established world order suffered critical damage due to the US misadventures in Iraq and, then, in Afghanistan. As an emboldened Putin and Xi Jinping call the shots, they are testing the will power of the West and the US,” says Yashwant Sinha, former foreign minister and current vice president of the Trinamool Congress.

Cost of Capitalism in Crisis

Many believe that the wave of national chauvinism and the rise of political strongmen are features of this age which is characterised by a vacuum in global power space. “I certainly see a connection between capitalism in crisis and the rise of strong sovereign leaders,” says Edward Ashbee, professor at the Department of International Economics, Government and Business, Copenhagen Business School. “But, I think that a feature of contemporary capitalism is fragmentation and creating rival centres of power. If we look at the Trump era, we can look at what Trump was able to do, but we must also notice what he was not able to do,” Ashbee adds.

The biggest critique of the post-Cold War globalised world order has been the increased disparity not only among sections of people within countries but also among countries. The 2008 global financial crisis stalled the pace of growth among developing nations, such as Ethiopia, India, Bangladesh, South East Asian countries, Kazakhstan and many more. “Meanwhile, within countries, inequality has risen fast everywhere, due to globalisation and the lack of adequate domestic policies to spread its benefits,” says Tiberghien.

A queue outside McDonald’s first restaurant in Moscow that opened on January 31, 1990. Photograph: Getty Images

It is crucial to balance growth with a sense of access and inclusivity for all. With capitalism in crisis, inequality has risen dramatically in many countries, which threatens political stability in many countries. The experience of most east European countries, which became the subject of the Western capitalist expansion after the fall of the USSR, is a case in point. “The transition to capitalism has fostered tremendous inequality in countries where, during socialism, economic inequality of this scale was unimaginable. Like neoliberal capitalism everywhere, eastern European countries have witnessed the upward redistribution of wealth. Economic indicators may move upward, but the guaranteed minimum wage remains low in many countries. What is even worse is that large segments of the workforce are stuck at that low level,” says Ileana Nachescu, assistant teaching professor in the Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Rutgers University.

January 31, 1990, might not have immediate recall for its historical significance, but its was a day to remember for the people of Moscow, as McDonald’s opened its first restaurant in the then Soviet Union. Thousands queued up for their first bite of Bolshoi Mac; the scenes that day were memorable in symbolism as the icon of American capitalism had been planted at the heart of communist USSR. More than a year later, the Soviet Union had disintegrated. And, more than 30 years, later that burger is not very juicy anymore, not only because McDonald’s suspended operations in Russia in the wake of the war with Ukraine but also because the American model of capitalism and globalisation is under tremendous threat, the world over.

“Rising inequality, unemployment, concentration of wealth among other ills have led to the American model of capitalism being questioned. But, it is not the model but the political economy that has allowed policies to be dictated by the rich and the strong that is behind the ills,” says Himanshu, associate professor, at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University. He points to the Indian experience where even 30 years after liberalisation, economic policies are still being adapted to suit the interests of few business people. “The model of capitalism has changed, but the essence has not”.

Widely seen has a growth propellant, the American model of capitalism and globalisation has only led to movement of capital from one country to another and from one strata of the society to the other, giving rise to widespread inequality and resentment. While the Scandinavian and Nordic experiences remain a contrast, they have remained limited in adoption by other countries, for obvious reasons.

China’s Stealthy Moves

These are cracks caused by the US-led world order that China and its recent ally Russia want to exploit as they use everything in their rule book from statecraft to seduction to keep authoritarians in power. Its notable example was Russia’s intervention in the 2016 Trump presidential campaign.

For Russia and China, this exercise, in a way, gives legitimacy to their own illiberal use of state power. More importantly, it ensures that their control is gradually fastened upon their ally countries, in the process elbowing out the US influence.

For Putin, the path to restoring the Russian glory of the Cold War era lies in military expansion, as shown in its aggression on Ukraine, and threats of a nuclear war. As he upends all rules that define global peace since the Second World War, Putin’s endgame becomes hazier. But, for Xi Jinping, China’s move to the top of the global table is clear from the Chinese statement during its virtual meeting with the top leadership of the US on March 18. In no uncertain terms, the statement read the following: “As permanent members of the UN Security Council and the world’s two leading economies, China and the US must not only guide their relations forward along the right track but also shoulder their share of international responsibilities and work for world peace and tranquillity.”

In simple words, China is not content with being a junior trade partner of the US. China may not want to change the US-led world order in any definitive manner, but it surely wants its “rightful place” in a geopolitical grouping that has America and China as dual leaders.

While China pushes for a bigger role, Sinha thinks it is not just about geopolitics. Instead, it can have implications for the values the current order stands for. “It is the Western value system of democracy and liberalism versus the Russian and Chinese model of autocracy. And, the warning signs are clear: in future democracy will be tested further,” says Sinha.

China’s ambitions can have catastrophic implications for globalisation. At its core, China’s statement harks back to the 19th century imperialism in a restrained manner. “It means that we are in a historical interregnum. And this leads to several scenarios. First, there could be a negotiation among systematically important countries, like G20. Unfortunately, the big countries are unable to agree on almost anything at the moment, due to the US inability to engage in such a grand bargain negotiation and due to the profound US-China equation. Second, we could see a messy hybrid situation where elements of global order endure along new regional cooperative solutions, tactical ad-hoc cross-regional alliances, like the Quad, and other forms of rule-making,” says Tiberghien.

US president Joe Biden participates in a virtual meeting with Chinese president Xi Jinping at the White House in November 2021. Photograph: Getty Images

In Xi’s scheme of things, as he subverts rules to seek a third term as the head of the Chinese Communist Party, the Ukraine war is central to his ambitions. Though macabre in its manifestation, the outcome of this war will tell if his tech tools are potent enough to subvert sanctions by the West and yet remain in business. This war will prepare him for his designs against Taiwan. Above all, at the behest of Putin, Xi is testing America and the West’s resilience against autocracies.

There can be a few other options too, each one of which can be more detrimental to global peace than the other; if China’s unsatiated ambition does not lead to a direct war with the US, it can surely disturb peace in its neighbourhood in all directions. The economic shocks of such a prolonged confrontation will lead to worldwide unrest and chaos with some countries going under.

Sinha predicts a future of jungle order ruled by strongmen. “It will not be easy to dislodge the US, but its might has been severely challenged. From here on, there will be no superpower. It will be a world where the strong will crush the weak. It is the jungle order,” he says.

The US in the New World Order

While capitalism enters into a phase of crisis, other challenges have emerged which can shape the new world order. The pandemic still looms large, whose economic and social impact needs a coordinated global response. At the same time, climate change threatens to upend human civilisation in the next 30 years. The moment is upon all nations to unite in action against this impending catastrophe. The next three decades could be crucial in deciding the future of humankind. A united set of actions is not possible without global peace. It appeared farcical when the UN, ahead of the climate summit in Glasgow last year, released a video with a talking dinosaur, Frankie, exhorting the world to not choose extinction and instead sit up and unite in action against the impending climate disaster.

But, when emotions are running high as countries race to create a new world order based on dominance, only Frankie and a miracle could save the next few decades.

With input from Neeraj Thakur and Sneha Kanchan