Reminiscent of the billionaires’ space race in America, a similar contest has begun in India. It is the race to dominate green hydrogen, or GH2, which is increasingly getting to be known as the fuel of the future. This race is being dominated by the world’s two richest men: Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani. Massive investments have been promised, great intent expressed and hectic acquisitions initiated, with competition intensifying at each step.

When Ambani announced a $10 billion foray into new energy in June, Adani doubled it with an announcement of a $20 billion investment in November, and it was a matter of time before the former would up the ante. In January, Ambani committed $75 billion to develop an entire green hydrogen ecosystem from electrolyser manufacturing to generation plants and solar panels.

As India aspires to become a global hydrogen hub and net exporter, the moves of the two billionaires are likely to lead the way for the country. “Hydrogen is the trigger for the smarter use of other renewables by becoming the long-term transport and distributed storage solution for electricity. It is the key link in the energy transition journey that, along with wind and solar, will stabilise decentralised power generation,” Gautam Adani told Outlook Business. “This was impossible to even contemplate just five years back. Such is the power of unification of technologies that create the most disruptive business models,” he added.

Both billionaires owe their fortunes to carbon businesses, but unlike the space race that has grave impact on the atmosphere, Ambani and Adani have chosen clean fuel as their future bet. Known for having a canny business sense of sniffing industry trends way ahead of others, their GH2 moves have ensured that public sector undertakings (PSUs) and other private companies have also followed suit.

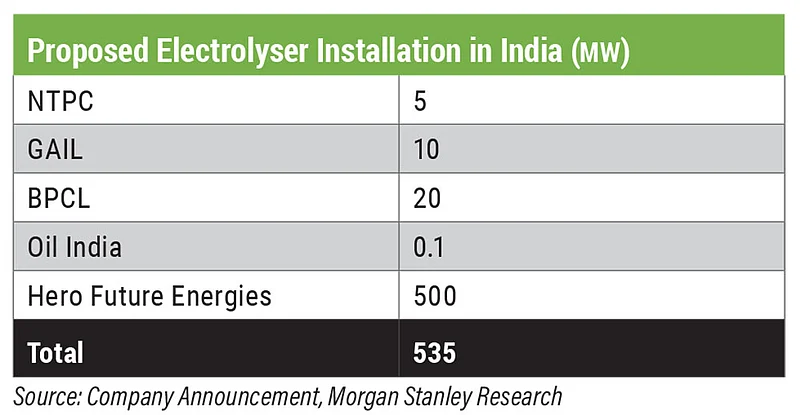

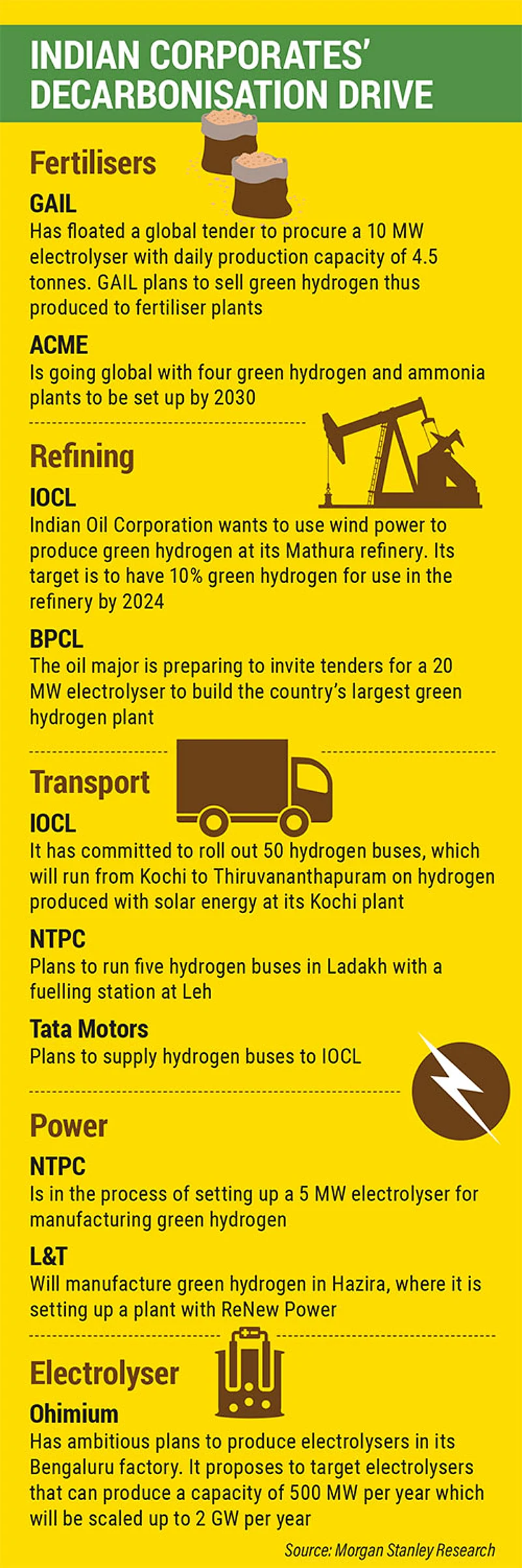

There is a frenzied action in the green hydrogen space: India’s largest refiner Indian Oil Corporation has announced partnerships with construction major Larsen & Toubro and renewable energy major ReNew Power. Other PSUs have also jumped into the fray: NTPC has floated tenders to create hydrogen fuelling stations and hydrogen blending in city gas distribution. GAIL has also floated tender for building an electrolyser capacity, while Oil India plans to set up a green hydrogen plant in Assam. At the same time, ACME India has announced green hydrogen and ammonia plants in Rajasthan and Oman, while Ohmium has announced an electrolyser manufacturing plant in Karnataka.

While many more are expected to throw their weight behind the emerging hydrogen ecosystem, all eyes are on the two businessmen from Gujarat, as they furiously write cheques for acquisitions and expansions. The path these tycoons take will define how the third largest carbon emitter in the world honours its climate commitments while cutting its import bill.

Freedom from Imports

In 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had vowed to bring down India’s oil imports by 10% by 2022. Ironically, the import bill, as well as its quantity, both have grown in this period. Due to the lower-than-expected production from PSUs and hydrocarbon explorers in the private sector, India’s import bill surpassed $100 billion in FY22.

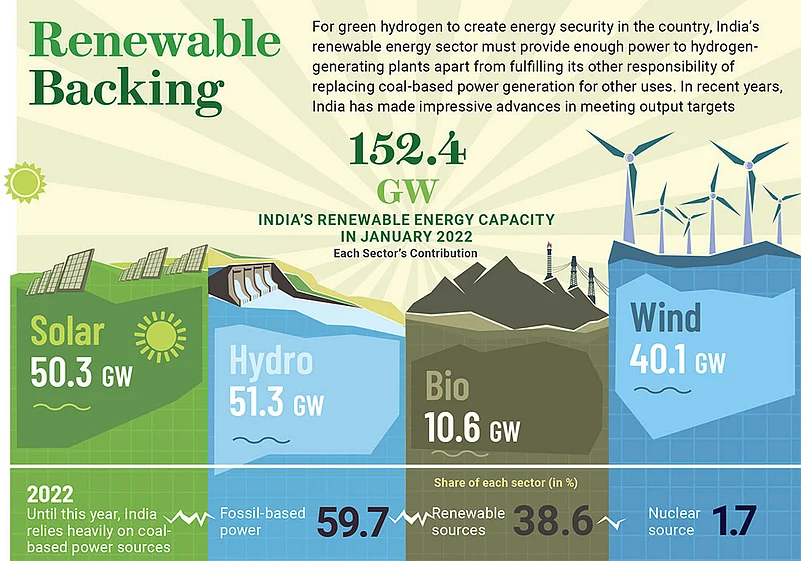

At the time of announcing his ambitious targets, Modi had miscalculated India’s rising demand for energy and solar energy’s inability to meet peak demand in the absence of storage capacity. Humbled by his experience, Modi has revised his targets with a touch of reality. Now, instead of keeping a short-term target for reducing oil imports, he has set the target of achieving energy independence by 2047 and chose the last Independence Day to announce it: “India today is not energy independent. Energy imports in the country account for an average Rs 12,000 crore a year. Energy independence is vital for India’s development. Hence, today, India must resolve to become energy independent by 2047, and our roadmap is very clear on this.” Meeting the new target depends upon a number of factors, including electrification of the Indian Railways, increasing blending of ethanol in petroleum products and a breakthrough in green hydrogen production capacity with the help of a domestic industry, which must focus on innovation and indigenous electrolyser manufacturing.

“… [S]omeday India can become a net green energy exporter! Hydrogen and its derivatives can replace a significant amount of our imports of crude oil, natural gas and coal,” says Adani.

But, unlike Adani or the government, Anish De, global sector head, power and utilities at KPMG, has a practical view on the scalability of green hydrogen. “A large economy like India will always be dependent upon imports to meet its energy needs, though green hydrogen will definitely bring down our energy imports,” he says.

Game of Thrones

Will hydrogen be the battlefield for the ultimate supremacy between Ambani and Adani? The answer to this question is not simple. Both men are openly keen to dominate this fuel of the future, and these are early days both for the GH2 technology as well as their plans for it. More importantly, never in the history of their operations have the two men directly competed against each other at scale.

“With retail and telecom now taken care of, new energy is the new area of business for Reliance Industries Limited (RIL). Look at the company’s performance. It is likely to close the year with cash profits of Rs 75,000 crore. You have to invest it in new business opportunities,” said an RIL associate, who did not wish to be named. And this “new business opportunity” is green hydrogen.

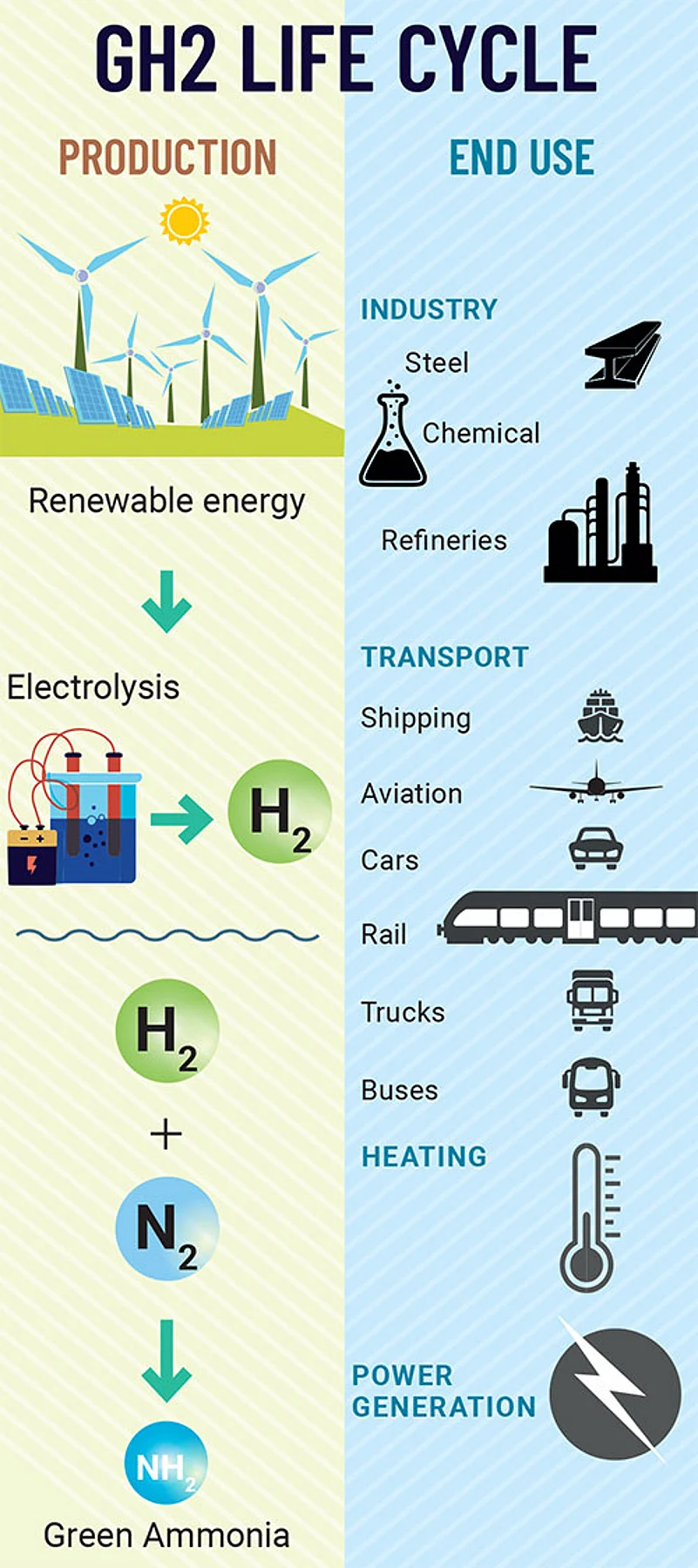

The path from grey to green hydrogen is going to be challenging, the two most important aspects for it being demand creation and cost reduction. While the industry will look to the government to create demand, the work of sustaining and growing this demand by making GH2 affordable will lie partly with policymakers and India Inc. We will come to the government’s role in a bit. Let us first concentrate on the two tycoons we began with.

For both billionaires, the process to manufacture affordable GH2 lies in controlling the entire production chain. Interestingly, neither of them controls all the pieces of the full puzzle.

While Adani was winning the renewable race with his installed solar and wind capacities till GH2 became a buzzword, Ambani is now ahead with the quantum of investment and acquisition announcements. Reliance’s partnership with Stiesdal gives it control over electrolysers to harness hydrogen from water. Its investments in NexWafe and the acquisition of REC Group and Sterling Wilson Solar will allow Ambani to “green” the electrolysis process using solar power, and Lithium Werks, Faradion and Ambri Inc. will enable GH2 storage. In fact, with Ambri Inc., Reliance is exploring the calcium antimony technology, a step towards the future of storage of GH2 with wide implications on cost reduction.

While Ambani is currently setting up the GH2 production chain, Adani, with his installed renewable energy (RE) capacity of over 10,000 MW, already has one production input in place. To advance his green hydrogen plans, his newly formed Adani New Industries Limited announced a strategic partnership in February with Ballard, a Canadian firm with leadership in fuel cell technology.

“While there are many challenges still to be addressed, I am confident that we are on the cusp of a hydrogen-driven revolution that can transform India, green India and energise India. This is nation building at its best,” says Adani.

Green Commitment

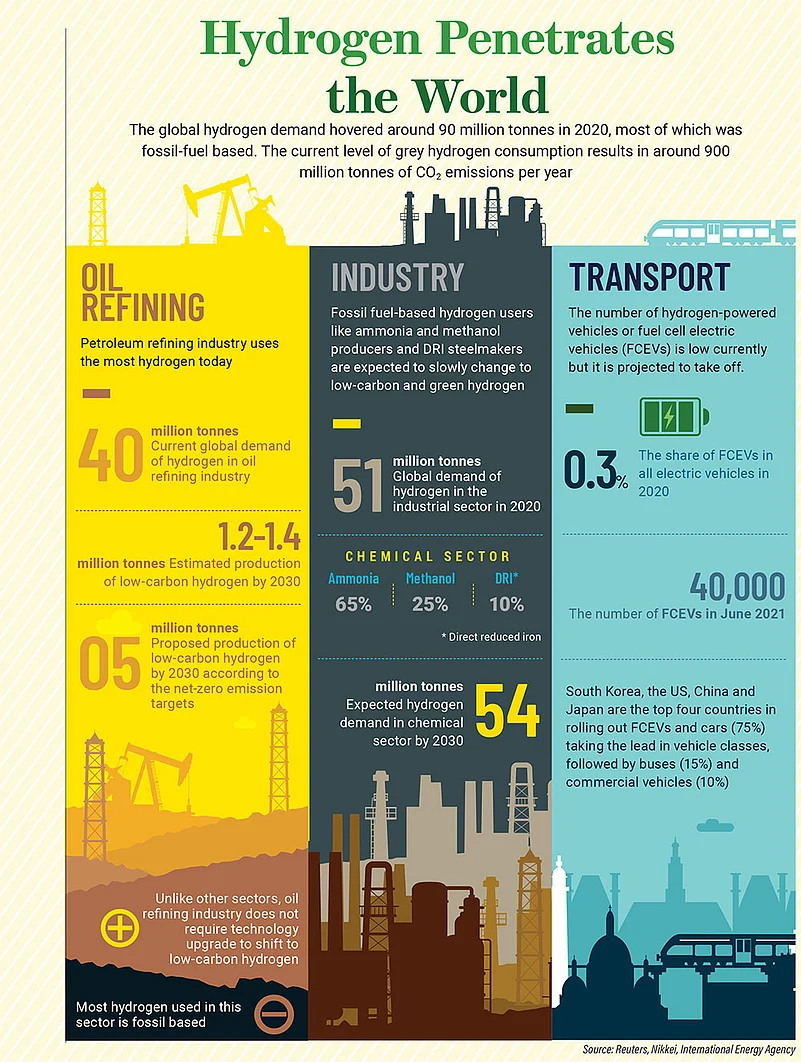

Far away from the shores of Gujarat, in November last year, 32 countries, including India, and the European Union came forward in one of the Glasgow Breakthroughs at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) to ensure that “affordable renewable and low-carbon hydrogen is [made] globally available by 2030”. The other “breakthroughs” relate to clean power, zero-emission road vehicles and near-zero-emission steel.

The breakthrough is aligned with the global agreement to limit the rise in world temperature to 2°C above the pre-industrial levels and have net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

In this context, GH2 has emerged as a viable solution for emission reduction due to drop in renewable energy costs and increasing maturity of technology. GH2 is particularly useful in hard-to-abate sectors and for overcoming intermittent nature of renewable sources, like solar, by offering storage solution.

It is only natural that India, too, has joined the green hydrogen bandwagon.

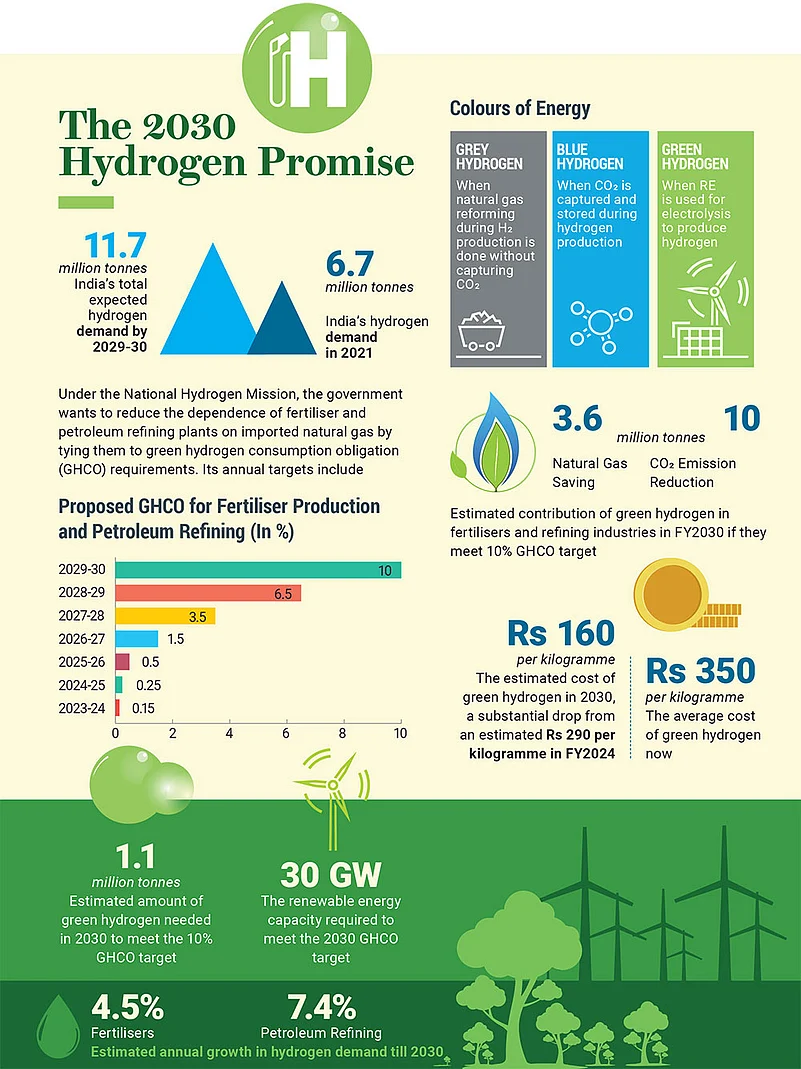

With the National Hydrogen Mission it has set a production target of five million tonne of green hydrogen per annum by 2030 and associated development of renewable energy capacity. The recently launched green hydrogen and green ammonia policy seeks to create an enabling ecosystem for purchase, storage and transmission of renewable energy, the much-needed input for greening the process of hydrogen production.

“The current framework is indicative that in the short term, the GH2 market will be a push market. The ability of the policy efforts to create a sustained demand pull will be important to create the necessary demand and help the market transition to a pull market,” explains Rakesh Jha, director, sustainability, management consulting division at Fichtner Consulting Engineers.

Can India Afford Green Hydrogen?

The keenness to jump into the green hydrogen ecosystem shown by the two Gujarati tycoons could take care of the required investments, but both will need ample support from New Delhi’s policymakers to sustain their interest through demand creation and interventions to bring down the cost of production.

“Today the biggest challenge is the cost differential between available sources of H2 and GH2. Green Hydrogen is twice or more as expensive as its grey counterpart. This requires collective work of government bodies, policy makers and industrial players,” says Derek Michael Shah, senior VP and head, green energy business, L&T. “The other challenge is availability of cost-competitive and efficient electrolysers in India.”

The Phase I of the National Hydrogen Mission, announced earlier this year, provides incentives to the sector, which are aimed at reducing the cost of RE. These include concessions on renewable energy rates, exemption from inter-state transmission charge on RE for 25 years and a 30-day banking facility for renewable energy generated to produce green hydrogen. Banking is a provision to allow RE generators flexibility to deposit and withdraw excess power from the grid. “The idea is to bring down the input cost of renewable energy for GH2 producers and increase efficiency of electrolysers through banking,” says a government official, who did not wish to be quoted. He added, “Banking is expected to increase the efficiency from 20% to 80%, thus bringing down the capital expenditure required to set up electrolysers.” Other incentives include a single-window clearance for GH2 producers, easy access to land in RE parks and storage at ports.

Ambani has vowed to produce GH2 at $1/kg, an 80% reduction from its current price, which is lower than most projections made by global players. The government wants three-fourth of green hydrogen to be produced through green energy sources by 2050 at a cost that can match the price of other energy resources like natural gas and coal.

But, despite the declared policy measures, it is not clear if the cost of producing GH2 can be brought down to the extent that it becomes cheaper than other energy sources. “Further policy actions should consider a push in the form of fiscal incentive, such as production-linked incentive schemes or feed-in tariffs, easy financing and benefits to spur R&D spending, which is critical to enable the desired level of investment and commercialisation efforts from big players, such as RIL,” says Jha.

P.C. Maithani, a former advisor to the Ministry of Renewable Energy, feels that India needs to target indigenous electrolyser industry. “If we focus on having domestic production of electrolysers, only then can we bring the cost of producing GH2 down. We missed the bus of producing solar technology trends. But, for hydrogen, every country is in the initial stages of technology development. If we incentivise the production side through targeted approach, it will help India in the long run,” he says.

Unlike developed countries, India cannot afford to put billions of dollars to provide upfront subsidy to promote domestic manufacturing of electrolysers, it needs to look for innovative ways to push demand. Apart from giving mandate to the cash-rich PSUs, the government’s plan to provide graded targets to the industry is a step in the right direction.

The government wants to mandate industries such as fertilisers, refineries and steel to use GH2 as 10% of its fuel to fire factories. Other demand areas identified by the Centre include long-haul transport, shipping and GH2 blending in gas grids, say sources in the government. In this demand push, the Solar Energy Corporation of India has been given the job of floating tenders for GH2 procurement to supply to the industry.

Given India’s ambition of becoming a GH2 hub, the government has already called its trusted lieutenants in PSUs into action. “It makes sense for PSUs to get into the green hydrogen business, as it will allow them forward integration of their business. Many of them are huge consumers of grey hydrogen already and have its use case within their business. In such cases, the alignment is stronger,” says De.

Energy PSUs account for seven of the country’s 10 maharatna firms, having an annual turnover of more than Rs 25,000 crore. They have all charted out plans to set up green hydrogen facilities over the next few years. “Indian Oil Corporation has drawn a strategic growth path to focus on its core refining and fuel marketing businesses, while making bigger inroads into petrochemicals, hydrogen and electric mobility over the next 10 years,” said its chairman Shrikant Madhav Vaidya at the time of announcing its plan to venture into green hydrogen production at its Mathura refinery.

Hope in Uneven Transition

While the government draws up plans to boost demand and increase affordability of green hydrogen and ensure private and public investments, challenges like limited transmission and distribution infrastructure continue to exist. Given that it is highly inflammable, storage- and safety-related concerns also worry stakeholders. “Therefore, the transition from grey to green hydrogen in key consuming sectors, such as fertilizer and refineries, is not immediately viable. Large-scale production capacity, driven by fiscal and export incentives and other regulatory measures, such as GH2 mandates for energy-intensive industries, will be instrumental in creating demand for GH2,” says Shubhranshu Patnaik, partner, Deloitte India.

But, beyond these challenges, there is a stereotypical villain as well in India’s energy script. In this case, it is the DISCOMs. These financially stressed utilities play an important role in the country’s energy ecosystem and are biased towards older ways of working in the fossil fuel-based energy distribution system. The cost of input electricity is about 50% to 60% of the cost of producing GH2. The Centre’s incentives could bring down this cost by 30%, but debt-ridden distribution companies are unlikely to play ball and state governments too may find it difficult to offer concessions, including land price, cost of electricity, etc. The spirit of the Centre’s renewable energy incentives is open access, and the DISCOMs’ aversion to it is well known.

“The mentality of DISCOMs is changing because they have realised that renewable energy is cheaper than the conventional source of power, but their role is still a big issue. The Central government is on board on what needs to be done, but state governments are just not there,” says Sumant Sinha, chairman and CEO, ReNew Power.

If Modi must keep his Glasgow promise and India save the world from a climate catastrophe, both Ambani and Adani will have to succeed with their green hydrogen plans. And, for that to happen, New Delhi will have to address the challenges with a robust policy that goes beyond a vague “Mission”, sort out the mess at power utilities and ensure that adjectives synonymous with Indian policymaking—read “flip-flop” and “paralysis”—are erased from investors’ minds. Apprehensions about a re-run of the problems plaguing India’s solar sector remain among many. “There were concerns on curtailment of power, bankability of projects, renegotiation / termination of power purchase agreements in renewable sector. We believe, the government is already working upon same and take care of these aspects while promoting Hydrogen,” says an optimistic Shah of L&T.

It is unlikely that the two Gujarati tycoons will collaborate in their hydrogen missions, but it here that the government could play a role by ensuring a level-playing field and equal opportunities beyond a duopoly.

That might be a tall order, but, perhaps, this is our only shot at sustainability.

With input from Shailaja Tripathi