2017: the year many Indians remember for the rollout of Goods and Services Tax (GST) after a dramatic midnight session of Parliament. For many, it was also the year they lost their job. According to the National Sample Survey Office’s findings, the unemployment rate was at a four-decade high between July 2017 and June 2018. Some believed Donald Trump’s tough immigration policies were responsible for Indian IT companies handing out pink slips like candy. Others blamed political masters closer home. It didn’t matter who did it, but someone pulled the rug from under Joy Bagchi. An engineer who had been working in Bengaluru, Bagchi had to return to his Delhi home and start living off his younger brother’s savings. It was then that Bagchi remembered a long-forgotten dream. He had always wanted to be a yoga instructor, but his family, dominated by his professor father, insisted he becomes an IT jobber and that’s what he did. Now, he had a chance to reinvent his life. Thanks to Urban Company (UC), he could.

He was already certified to work as a yoga instructor and, after registering on the UC app, requests poured in.

Just like Bagchi had reevaluated his choices a year ago, in 2018, Urban Company did too. It had started operations in 2014 as Urban Clap, on a mission to revolutionise (read: standardise and provide reliable) home services. It was a vast area to cover. In 2018, UC realised it was juggling too many balls—from chasing pigeons away from people’s balconies, to helping organise weddings.

Perhaps this stretching-too-far came from the founders’ early days. Varun Khaitan and Abhiraj Bhal’s first venture was selling entertainment units for mass transport, and Raghav Chandra’s was an app to book autos. Both ventures shut shop within months. Their learning was that they were going after too small a market opportunity.

Four years after founding their first highly successful start-up, they had to unlearn. They were beginning to realise that bigger wasn’t always better.

“The model that we run today is very different from the UC model that we started with,” says Khaitan. Where once they offered 100 services, today they don’t list even 10. They now cater only to home (cleaning and appliance maintenance) and grooming needs. “There were several mistakes made to get to the right answer,” he says.

They have cracked the right answer all right.

UC is today Asia’s largest online professional home-service provider. Within a year of streamlining categories to offer full-stack services, the company expanded to 37 cities from 8 to 10 cities in 2018.

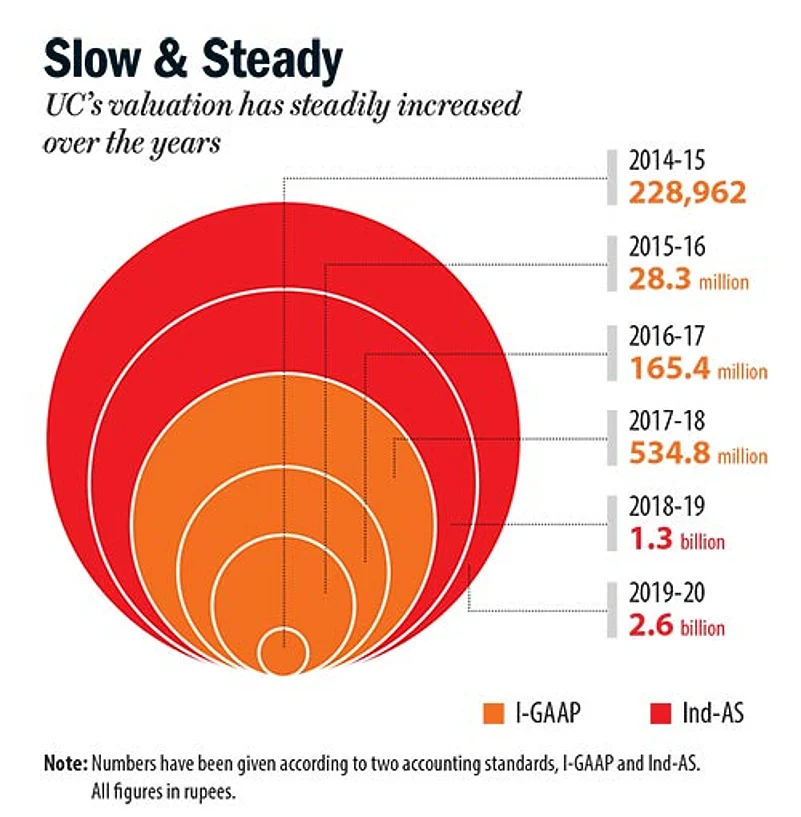

This April, the start-up became a unicorn.

Scaling down for higher growth as a business strategy is widely accepted, but it can be a painful process for the founders of a start-up. Khaitan compares it to the agony of choosing from among your children. “Of what we did, you could say 90 per cent did not work. But I had to do all the 100 to get a sense of which services have more demand, which services have real pain points and how they can be solved,” he says. They learnt that there are two kinds of services—ones that can be standardised and ones that can’t be. A facial or a plumbing service would fall in the first category, while a wedding photographer or a marriage counsellor would fall in the second. UC chose to dabble in the first category.

It was a leap of faith. “When we shut down the non-standardised services, we stood to lose 50 per cent of the revenue of the company,” Khaitan says. They went ahead with it anyway.

They moved their focus away from doing everything for everyone and instead trained it on customer experience. “For any internet business, ensuring customer experience is the key. With non-standardised services, we could not control that,” explains Abhinav Chaturvedi, partner at venture capital firm, Accel, one of UC’s early investors.

Another game-changing decision by UC to improve the quality of customer experience was eliminating the middleman—a dreaded spoke in the wheel for anyone doing business in this country. They began working directly with service providers and training them.

“Throughout our journey, we have taken such calls where we have chosen depth over breadth, quality over quantity,” says Raghav Chandra, co-founder of UC. They opted out of everything they could not excel at.

Like Accel, several of the company’s investors helped them decide which services to discontinue. Besides the degree of standardisation possible, a service was also retained or discarded based on its frequency of use—for example, a salon service needed once a month was to be retained, while a wedding photography service needed maybe once a year was to be thrown out of the window. The founders resisted Marie Kondo-ing their portfolio.

“We were stubborn for a long time. We were like ‘no, the other part (the non-standardised service vertical) is also working and that we’ll make it work and that we are (working) hard at it’,” remembers Khaitan with a laugh. But difficult decisions had to be taken and Bagchi’s services as yoga instructor were no longer offered by UC’s platform. That said, Bagchi did get a headstart in a profession of his choice and had developed a clientele by the time UC ‘scaled down’.

Around the time UC launched in 2014, the idea of disrupting the home services market with technology was already being discussed. Over the years, when Housejoy and Joe Hukum failed to scale up their home services business, and Dunzo shut its corresponding vertical, UC survived and thrived. While others changed course—Housejoy moved into the construction business, Joe Hukum began making chatbots for businesses and Dunzo put all its energy into making local deliveries—UC held its ground by realising quickly the folly of spreading itself too thin and taking corrective action.

Khaitan does not make too much of it. He knows mistakes are easily made and that they are not easy to solve for a sector characterised by a trust deficit. “In hindsight, you can call it a mistake but, even if I had to do it again, I would probably do it the same way because there was no other way to know,” he says.