"Video killed the radio star,” sang The Buggles way back in 1979, when radio hadn’t even taken off in India. All we had then was All India Radio, a government monopoly. Not many of us will be familiar with the AIR theme song today, but it was omnipresent — you’d hear it everywhere, in people’s homes and portable transistors.

Fast forward to today — this medium has been dwarfed by print, television and in the more recent past, digital as well — just what The Buggles was crooning about. Ironically, radio touches the lives of more people in the most economical way. For no more than a few hundreds, a person can buy a radio set and instantly listen to the latest Bollywood hits and remixes, or even playlists from the golden days of Indian music. If you tune into AIR, you can also listen to the news or cricket commentary.

While FM radio came into its own in the early ’90s, when the government sold airtime in a few cities to private players, the real turning point came when the government opened up 108 frequencies for private players in 2000. Today, there are 386 radio stations operated by nearly 30 private players.

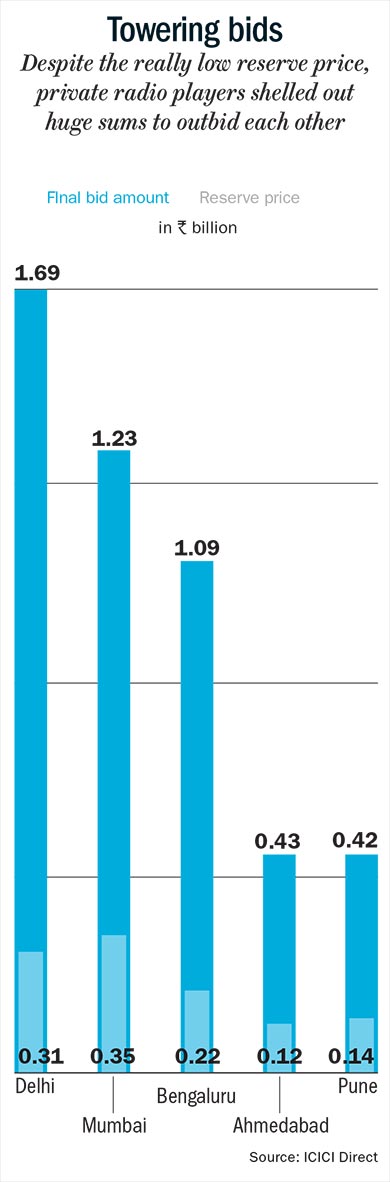

It’s not been an easy journey. The players got frequencies, but face certain restrictions. For one, they aren’t allowed to broadcast news, which means content is largely around music. The luxury of delivering news is only AIR’s domain. Another major hurdle for the private players is exorbitant licence fees (See: Towering bids). It can cost over a billion rupees in major cities such as Mumbai and Delhi and this amount can only be recouped through advertising. In contrast, satellite television has been breathing easy for a few years now, since the industry follows a subscription model, reducing the dependence on advertising. Then, the license is only valid for 15 years, whereas for satellite television, it is for perpetuity.

Despite the high upfront costs to set up a station, the radio industry just gets 4-5% of the total advertising spend of Rs.600 billion. Print and television account for 32% and 38%, respectively. Radio has been left behind by the newest form of media as well — digital, that enjoys 19% share.

Evidently, the struggle for growth is altering the industry structure. It has led to a few M&A deals, leaving only the big boys who can afford to stay in the game. These biggies are trying to change the landscape and complementing the radio stations with their existing media business, most notably print. This means there is none or very limited space for the smaller folks. And it is this pressure that has bruised many a radio business. In 2018, Radio One, owned by Next MediaWorks, sold out to HT Media for Rs.3.20 billion. Meanwhile, Reliance Broadcast Network’s Big FM is set to be acquired by Jagran Prakashan-owned Music Broadcast for an enterprise value of Rs.10.5 billion. From the looks of it, the M&A story in radio is yet to reach a crescendo.

Jingle money

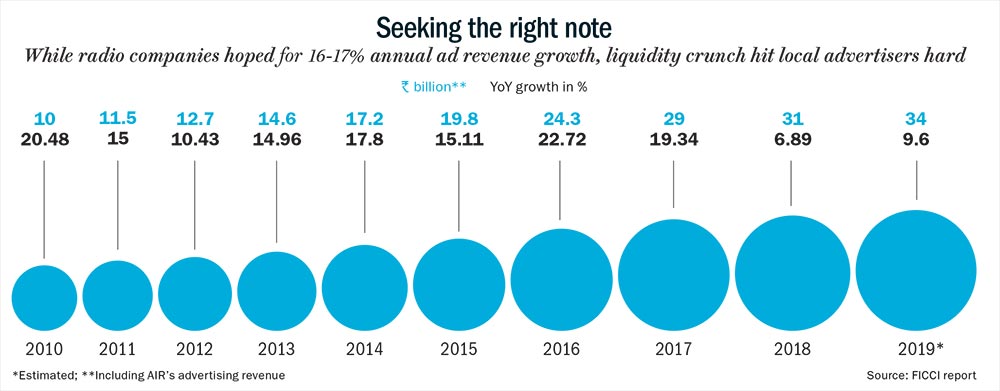

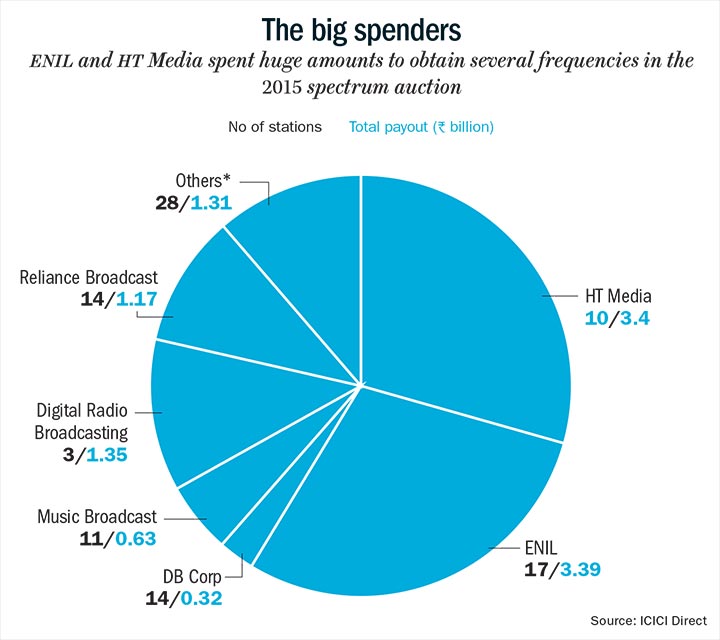

In 2018, 47 new stations owned by various players including Entertainment Network India (ENIL), HT Media and Music Broadcast went live — the third phase of auctions for frequencies in 2015 saw the government raking in Rs.11.57 billion. HT Media, the most aggressive bidder, won licences to operate ten stations, paying a whopping Rs.3.40 billion. Of this, the company paid Rs.2.92 billion only for Delhi and Mumbai. Naturally, eyebrows were raised at the bid. In 2017, all the radio stations combined grossed Rs.29 billion in advertising revenue, with the number growing by just 7%, to Rs.31 billion last year. A FICCI-EY report predicts this year’s figure at Rs.34 billion, a 9.67% increase (See: Seeking the right note).

So, what is it that makes the business so challenging? Besides the massive licence fee that has to be shelled out upfront, the operators are also charged 20% of total revenue annually or a minimum cost of — Rs.30 million in Mumbai and Rs.42 million in Delhi. All this does not include the 2% royalty to be paid to the music industry. According to industry executives, a station has to churn out at least 2-3x total costs as revenue to stay profitable, depending on how well they can manage expenses. And that is a tough job for any radio player. Take the case of the largest company in this space. Having spent Rs.3.4 billion to obtain 17 stations in 2015, ENIL posted a net profit of Rs.1 billion in FY16, which then halved to Rs.551 million in FY17 (See: The big spenders). For HT Media as well, the total payout was over Rs.3.4 billion for 10 stations, and its Ebitda for the radio business fell from Rs.298 million in FY16 to Rs.103 million in FY17.

The licence fee is much less for smaller cities, but the advertising revenue is also low. For example, HT Media bought frequencies in Muzaffarpur for Rs.2 million, and Gorakhpur and Aligarh for Rs.3 million each. These ventures are not too attractive since the players cannot command higher advertising rates. For centres such as Nashik and Surat, a 10-second spot costs only Rs.150, while it can be as high as Rs.1,300 in Delhi or between Rs.1,100 and Rs.1,200 in Mumbai and Bengaluru.

But why be in a business that has countless challenges and few rewards? According to Bhupendra Tiwary, AVP-research, ICICI Securities, aggressive bidding for the third phase of radio frequencies in September 2015 was driven by the assumption that advertising spend would grow each year by 16-17%. “However, local advertising not taking off has been a serious dampener, which has resulted in growth being at just 8-10%,” he says. The factors which played spoilsport include demonetisation, GST and the final nail in the coffin — implementation of the Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA) Act.

This has hit the players hard. Prashant Panday, MD & CEO, ENIL, speaks of how the recent NBFC crisis has also affected the industry. “Big advertising segments such as automobiles, durables, real estate and BFSI faced slowdown as a consequence,” he explains. The aforementioned FICCI-EY report states that the top five categories — services, retail, food and beverages, automobiles and BFSI — account for over 65% of total advertising spend on radio, with services alone at 30%. By Panday’s estimate, at least 50% of the revenue for the industry comes from local advertisers in these segments.

Due to the mentioned factors, local advertisers cooled off for over two years. Clearly, for the FM radio business to be sustainable, the local advertiser has to return. It has been close to eighteen years since Radio City rolled out India’s first private FM station in Bengaluru, but radio’s advertising story has had little to cheer about. And to survive, the strong operators are tuning the small ones out.

Merging frequencies

For HT Media, the reason to acquire was pretty clear — inorganic growth. Of its 15 stations across two brands (Fever and Radio Nasha), the company has eight stations in six metros. “The Radio One acquisition made strategic sense because we are metro-centric. The top cities contribute 65-70% of the industry’s revenue,” explains Harshad Jain, CEO – radio & entertainment, HT Media and Next MediaWorks.

There was another reason. Radio One has stations in seven metros and plays English music, whereas, HT Media’s stations play Hindi. With the acquisition, HT Media will deepen its presence and widen its target audience in existing markets. “We already have a contemporary hit radio format and English music addresses high net worth individuals,” adds Jain. That does not mean it will get easier for HT Media. Hindi is the most consumed and preferred form of music — making up at least 85% of the total music played on stations in the north, while the southern states play regional music. In FY18, Radio One reported revenue of Rs.800 million, and now, the task on hand is to boost its English music audience and bring in more advertisers.

In FY19, HT Media’s radio business reported operating revenue of Rs.1.94 billion; across 15 stations in 13 cities. Of this, it is estimated that Nasha contributed Rs.350-400 million, with the rest coming from Fever. With Radio One, its combined revenue is Rs.2.7 billion. Jain says Fever and Nasha have hit breakeven on an operational basis, much ahead of their internal timeline. Radio industry executives, like him, go to great lengths to explain how their stations are uniquely positioned. Fever FM has the 25-35 age group as its target audience, while Radio Nasha is for those in the 35-45 age band. Radio One, with English music, is a different audience altogether. “We offer unduplicated reach in the 18-50 age group, straddling mid-segment to affluent. That allows us to speak to a diverse set of advertisers,” says Jain.

There is some scepticism though about how sharp this segmentation really is and to what extent it can translate to more advertisers. More so when there are multiple stations playing the same music. Unlike print and television, where there are ways to measure readership and viewership, radio has no such mechanism, according to Tiwary. While IRS has a radio listenership survey, its scope is limited, unlike in print or television. These are still early days in India for radio listenership measurement. “That makes it difficult to create stickiness as it is hard to figure out who is listening to which station,” he says.

Then, there is changing dynamics. Gautam Radia, MD, Hit 95 FM, a station operating in Delhi since 2006, says regulator TRAI has recommended digital radio to the government. But several big radio broadcasters are not in favour due to the fear of unknown consequences. For instance, if the digital licensing fee is low, what happens to the already paid licensing fee? According to Radia, the FM business is indeed becoming one for the big boys. “The problem is the non-availability of new spectrum for many years, which has resulted in no innovation in programming. This has pushed the audience to OTT platforms such as Gaana, Jio Saavn, Spotify and Amazon,” he explains. Data becoming cheap is a trigger for the shift in listenership, though consuming radio through airwaves remains dominant, at least for now.

In light of this shift, the large investments that radio players have made may just not yield optimum return. Even as the bidding for metros such as Mumbai and Delhi reached astronomical highs, those for smaller centres were far more measured. Take the case of Rajasthan Patrika that paid Rs.124 million for 14 frequencies or Jagran Prakashan – which operates Radio City – that shelled out Rs.626 million for 11 frequencies. “The strategy was to bid in those places where their publishing businesses were strong. This has allowed them to sell radio as a part of a larger advertising bouquet,” Tiwary points out.

Jagran Prakashan, too, sees merit in its acquisition of Big FM (revenue Rs.3 billion, net loss Rs.6 billion), which, too, caters to a different target group. Apurva Purohit, president, says Radio City caters to the 25-44 age-group and Big FM’s core audience are those who are above 45 years of age. Their 39 stations will now be topped up by another 40 that Big FM runs, giving it a total of 79 stations across 69 cities. “Both the target groups are complementary giving advertisers an expanded consumer base,” she explains.

With these recent buyouts, the top four – ENIL, Music Broadcast, Sun Network and HT Media – enjoy combined revenue of Rs.18.50 billion or 60% of the total radio advertising market in India.

Interestingly, Radio City itself came to Jagran through the inorganic route. In late 2014, it acquired the company from Star India and India Value Fund Advisors. Unlike HT Media, Jagran was a lot more measured during the last round of auctions and, according to Purohit, “it did not overextend itself by bidding for costly multiple frequencies or a long tail of very small markets, which would have difficulty in breaking even.” The company focused on Hindi-speaking markets, where they had a print presence and that covered four frequencies in Rajasthan —Ajmer, Bikaner, Udaipur and Kota — of the total 11.

Stay tuned

Having lived through tough times, the industry believes the way forward is to build a mechanism for tighter cost control and bringing in a larger base of advertisers. The landscape still has niche players, who are trying different things. Radio Indigo 91.9 in Bengaluru plays only English music and has just launched its own app. Sanjay Prabhu, director, Asianet News, the holding company for Indigo 91.9, says the station has managed to rope in top-end advertisers such as Apple and BMW. “It has not been easy to expand over the past two years, with most of the money moving to digital advertising. That is why we have had to look at other avenues such as events,” he says. Prabhu claims his station pulls in advertising worth Rs.300 million and the strategy is to focus on a small base of top-end advertisers.

That’s every private radio company’s end goal today: get more advertisers to reach the 200 million Indians who listen to FM radio daily. But, maybe, there is an opportunity to build a radio business outside of advertising. And just like Radio Indigo, Radio Mirchi has taken the events route. What makes it a side option is that the margin here is much lower – 10% compared to upwards of 25% for a tightly run radio station. Tiwary believes foraying into events is not a piece of cake for a radio station, since it involves a gestation period of five to seven years. “It is a high fixed cost business and comes with its own risk quotient,” he says.

According to Panday, his effort is in building a business that goes beyond traditional radio. “The whole media sector is transforming and traditional media will see a significant slowdown due to digital disruption over the next five to 10 years. It is important to look at ways to reduce the dependence on advertising,” he says. The legendary Freddie Mercury may have crooned ‘radio gaga’ in 1984, but the industry is yet to see its finest hour. Will radio rise to the occasion? The jury is out on that.