In November last year, when the global population crossed the mark of eight billion, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) called it a world with infinite possibilities. But not all share the optimism. The disagreement in perception may have triggered concerns about population anxiety, a term used to describe people’s growing concern over the world’s population growth and its potential impact on several fronts, including the environment, the society and the well-being of individuals.

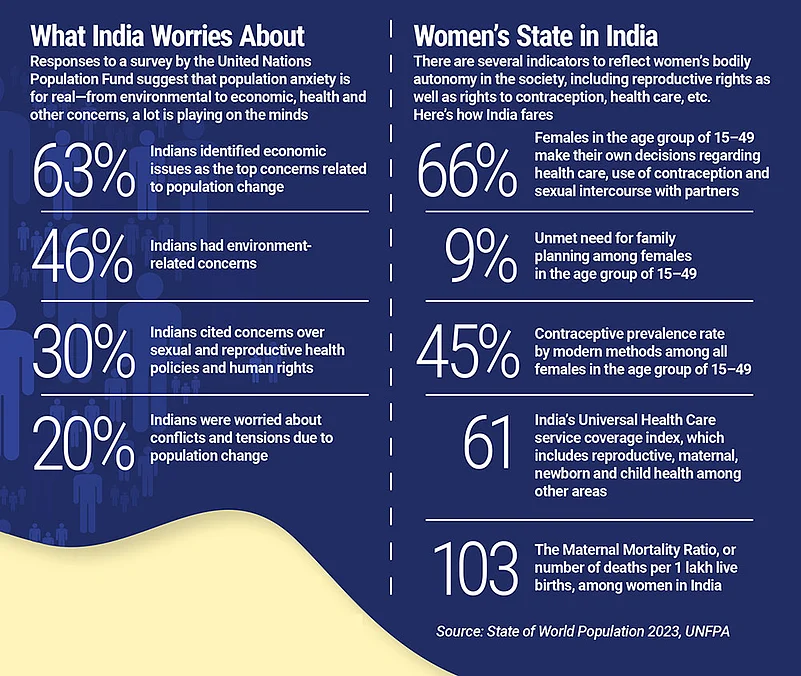

For Indians, economic concerns arising from population increase outweigh most others—the country officially became the most populous in the world last month—with a whopping 63% rating it as their biggest fear, according to the UNFPA’s state of world population (SWOP) 2023 report, titled 8 Billion Lives, Infinite Possibilities: The Case for Rights and Choices.

India is not alone. More than two thirds of the respondents from eight nations—Brazil, Egypt, France, Hungary, India, Nigeria, Japan and the United States—covered in the SWOP survey named various economic issues as their top concerns related to population change. Besides economic concerns, 46% of the respondents in India were worried about the environment, 30% about sexual and reproductive health laws and human rights and 20% about culture, ethnicity and racism.

One of the key concerns associated with population anxiety is the potential strain on the planet’s resources, particularly in areas such as food, water and energy. With more people consuming these resources, there is a risk of shortages, which could have serious consequences for vulnerable populations. Moreover, as the demand for resources increases, the pressure on the environment intensifies, leading to deforestation, land degradation and pollution.

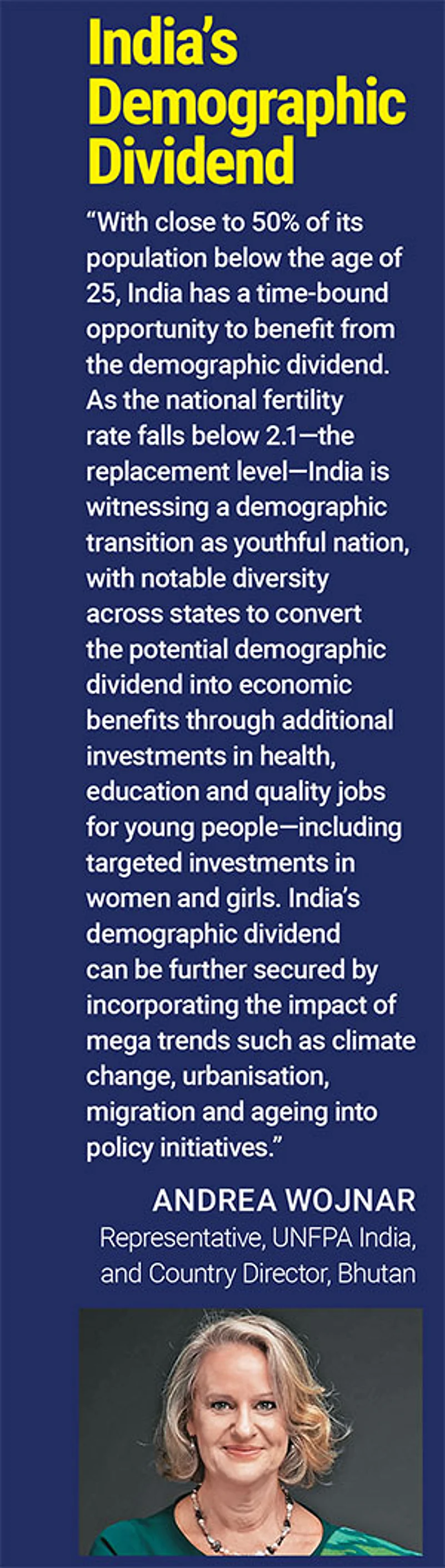

As per the United Nations projection, the world’s population is likely to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, with the fastest growth occurring in developing countries. This growth presents both challenges and opportunities. On the one hand, it can lead to increased demand for resources, environmental degradation and social and economic instability. On the other, it can also result in a demographic dividend if appropriate investments are made in health, education and employment.

According to the United Nations Development Programme’s 2022 Human Development Report, six in seven persons globally say that they feel insecure about various aspects. Against the backdrop of this observation, the SWOP report suggests that it is “too easy” to interpret the population figures as a sign of impending disaster. It refers to the fears about “overpopulation”, describing it as the perception that there are more people than the planet can sustain.

In Brazil, Egypt, France, Hungary, India and Nigeria, 53% to 76% respondents of the SWOP survey believed that the current world population was too large. Even in the remaining two nations, Japan and the United States, the larger share of the respondents held this view.

The report highlights a general concern over population growth and efforts by governments to gradually put policies in place to raise, lower or maintain fertility rates.

Human Rights Caught in the Crosshairs

When the world population reached eight billion, a worrying conversation about population issues gathered traction, warping the issue of women’s rights and their ability to make their own decisions regarding their bodies.

The UN has warned that growing “population anxiety” is forcing governments to enact detrimental fertility programmes that violate human rights and gender equality.

The SWOP report notes that 44% of partnered women and girls in 68 reporting countries do not have the right to make informed decisions about their bodies on matters of sex, contraception and seeking health care. Close to 257 million women worldwide have an unmet need for safe and reliable contraception.

According to the National Family Health Survey 5, there is 9.4% unmet need for contraception in India. Additionally, 23.3% girls get married before the age of 18 and 6.8% of total deliveries are among teenagers aged 15 to 19.

“So many women lack control over their bodies, including the right to have children and to decide when they want to have them and how many,” says Poonam Muttreja, executive director of Population Foundation of India, a not-for-profit organisation which advocates better policymaking towards creation of gender sensitive population.

Human reproduction is neither the problem nor the solution, says Natalia Kanem, executive director of UNFPA in her foreword to the SWOP report. “When the human numbers are tallied and population milestones passed, the rights and potential of individuals fade too easily into the background. Over and over, we see birth rates identified as a problem—and a solution—with little acknowledgement of the agency of the people doing the birthing,” she adds.

Social scientist and demographer Shireen Jejeebhoy, in an interaction with Outlook India in November last year, spoke about the excitement around India becoming the most populous country in the world which has caused some alarm in many quarters of the country. “Maybe some are using this as an opportunity to call for a two-child norm policy and penalties on those who have more. This is clearly a violation of people’s reproductive rights, as India has committed itself to people’s right to bear the children they want, without any interference or pressure,” she said.

However, she rued, reproductive rights are already being violated in several ways. “Nationally, one in 10 women and about one in six young women are not practising contraception despite wanting to delay or stop pregnancy,” she said, calling it a failure on the part of the national health system to deliver contraceptive services, which has led to violation of reproductive rights of women.

Policy intervention to control population, like in the case of China when it enforced the one-child rule, leads to violation of rights of people in general, and women in particular.

The SWOP report calls for a rethink on how population data is reported. “The question that needs to be asked is not just how fast are people reproducing, but are all individuals and couples able to exercise their basic right to choose how many, if any, children that they want? The answer to the latter, tragically, is no,” the report states.

“In spite of progress on many fronts, patriarchy is deep-rooted in the country, and this gets reflected in the performance of the reproductive health programme too. Almost the entire responsibility for family planning is on women. We need to move towards greater involvement of men in family planning. It is also important for more girls and women to get better educated, join the workforce, delay marriage and postpone pregnancies,” underlines Muttreja.

Many states across India have population policies that offer incentives to public and government officials who have two children but exclude them from the same if they have more than two children. However, such policies, even if being projected as voluntary, can lead to prenatal sex determination and sex-selective abortions.

Need for Higher Resilience

The catastrophic outcome of climate change is yet another argument which is being played to push for reducing the population numbers. “... [W]hile population numbers are essential to understanding climate concerns, fixating on numbers alone can obscure the actions that all countries need to take to meet these challenges, from cutting emissions to financing the efforts of poor communities to adapt to climate change,” the SWOP report states.

One takeaway from the report could be that while concern over any situation is acceptable, since it can lead to positive action, anxiety often tends to sabotage any latent advantages it may have. The concept of demographic dividend, also advocated by the UNFPA, tries to specifically drive home this point. According to the latest SWOP survey, 68% of the population in India is in the age of 15 to 64, which is also categorised as the working age population. Just 7% of the population is aged 65 or above. The availability of a huge working capital, if channelised properly, can be a boon, not a bane.

As the report suggests, decision makers can better build resilient populations not by setting targets and stifling choices but by pursuing policies that enable individuals to realise their own reproductive ideals and broader well-being. This would be a more productive approach than demonising population figures.

Whether one sees the current rise in numbers as pointing to an “explosion” or an “advantage”, resilience to demographic changes, while ensuring that human rights are not sacrificed at the altar, will be the key to determining a sustainable growth trajectory of nations. For this, policies must be backed by evidence, not opinions or fears.